Open PDF 129KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downbeat.Com December 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 . U.K DECEMBER 2014 DOWNBEAT.COM D O W N B E AT 79TH ANNUAL READERS POLL WINNERS | MIGUEL ZENÓN | CHICK COREA | PAT METHENY | DIANA KRALL DECEMBER 2014 DECEMBER 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Žaneta Čuntová Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Kevin R. Maher Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

MUSIC LIST Email: Info@Partytimetow Nsville.Com.Au

Party Time Page: 1 of 73 Issue: 1 Date: Dec 2019 JUKEBOX Phone: 07 4728 5500 COMPLETE MUSIC LIST Email: info@partytimetow nsville.com.au 1 THING by Amerie {Karaoke} 100 PERCENT PURE LOVE by Crystal Waters 1000 STARS by Natalie Bassingthwaighte {Karaoke} 11 MINUTES by Yungblud - Halsey 1979 by Good Charlotte {Karaoke} 1999 by Prince {Karaoke} 19TH NERVIOUS BREAKDOWN by The Rolling Stones 2 4 6 8 MOTORWAY by The Tom Robinson Band 2 TIMES by Ann Lee 20 GOOD REASONS by Thirsty Merc {Karaoke} 21 - GUNS by Greenday {Karaoke} 21 QUESTIONS by 50 Cent 22 by Lilly Allen {Karaoke} 24K MAGIC by Bruno Mars 3 by Britney Spears {Karaoke} 3 WORDS by Cheryl Cole {Karaoke} 3AM by Matchbox 20 {Karaoke} 4 EVER by The Veronicas {Karaoke} 4 IN THE MORNING by Gwen Stefani {Karaoke} 4 MINUTES by Madonna And Justin 40 MILES OF ROAD by Duane Eddy 409 by The Beach Boys 48 CRASH by Suzi Quatro 5 6 7 8 by Steps {Karaoke} 500 MILES by The Proclaimers {Karaoke} 60 MILES AN HOURS by New Order 65 ROSES by Wolverines 7 DAYS by Craig David {Karaoke} 7 MINUTES by Dean Lewis {Karaoke} 7 RINGS by Ariana Grande {Karaoke} 7 THINGS by Miley Cyrus {Karaoke} 7 YEARS by Lukas Graham {Karaoke} 8 MILE by Eminem 867-5309 JENNY by Tommy Tutone {Karaoke} 99 LUFTBALLOONS by Nena 9PM ( TILL I COME ) by A T B A B C by Jackson 5 A B C BOOGIE by Bill Haley And The Comets A BEAT FOR YOU by Pseudo Echo A BETTER WOMAN by Beccy Cole A BIG HUNK O'LOVE by Elvis A BUSHMAN CAN'T SURVIVE by Tania Kernaghan A DAY IN THE LIFE by The Beatles A FOOL SUCH AS I by Elvis A GOOD MAN by Emerson Drive A HANDFUL -

DJ Playlist.Djp

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE -

5713 Theme Ideas

5713 THEME IDEAS & 1573 Bulldogs, no two are the same & counting 2B part of something > U & more 2 can play that game & then... 2 good 2 b 4 gotten ? 2 good 2 forget ! 2 in one + 2 sides, same story * 2 sides to every story “ 20/20 vision # 21 and counting / 21 and older > 21 and playing with a full deck ... 24/7 1 and 2 make 12 25 old, 25 new 1 in a crowd 25 years and still soaring 1+1=2 decades 25 years of magic 10 minutes makes a difference 2010verland 10 reasons why 2013 a week at a time 10 things I Hart 2013 and ticking 10 things we knew 2013 at a time 10 times better 2013 degrees and rising 10 times more 2013 horsepower 10 times the ________ 2013 memories 12 words 2013 pieces 15 seconds of fame 2013 possibilities 17 reasons to be a Warrior 2013 reasons to howl 18 and counting 2013 ways to be a Leopard 18 and older 2 million minutes 100 plus you 20 million thoughts 100 reasons to celebrate 3D 100 years and counting Third time’s a charm 100 years in the making 3 dimensional 100 years of Bulldogs 3 is a crowd 100 years to get it right 3 of a kind 100% Dodger 3 to 1 100% genuine 3’s company 100% natural 30 years of impossible things 101 and only 360° 140 traditions CXL 4 all it’s worth 150 years of tradition 4 all to see (176) days of La Quinta 4 the last time 176 days and counting 4 way stop 180 days, no two are the same 4ming 180 days to leave your mark 40 years of colorful memories 180° The big 4-0 1,000 strong and growing XL (40) 1 Herff Jones 5713 Theme Ideas 404,830 (seconds from start to A close look A little bit more finish) A closer look A little bit of everything (except 5-star A colorful life girls) 5 ways A Comet’s journey A little bit of Sol V (as in five) A common ground A little give and take 5.4.3.2.1. -

All Audio Songs by Artist

ALL AUDIO SONGS BY ARTIST ARTIST TRACK NAME 1814 INSOMNIA 1814 MORNING STAR 1814 MY DEAR FRIEND 1814 LET JAH FIRE BURN 1814 4 UNUNINI 1814 JAH RYDEM 1814 GET UP 1814 LET MY PEOPLE GO 1814 JAH RASTAFARI 1814 WHAKAHONOHONO 1814 SHACKLED 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 20 FINGERS SHORT SHORT MAN 28 DAYS RIP IT UP 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU 3 JAYS IN MY EYES 3 JAYS FEELING IT TOO 3 THE HARDWAY ITS ON 360 FT GOSSLING BOYS LIKE YOU 360 FT JOSH PYKE THROW IT AWAY 3OH!3 STARSTRUKK ALBUM VERSION 3OH!3 DOUBLE VISION 3OH!3 DONT TRUST ME 3OH!3 AND KESHA MY FIRST KISS 4 NON BLONDES OLD MR HEFFER 4 NON BLONDES TRAIN 4 NON BLONDES PLEASANTLY BLUE 4 NON BLONDES NO PLACE LIKE HOME 4 NON BLONDES DRIFTING 4 NON BLONDES CALLING ALL THE PEOPLE 4 NON BLONDES WHATS UP 4 NON BLONDES SUPERFLY 4 NON BLONDES SPACEMAN 4 NON BLONDES MORPHINE AND CHOCOLATE 4 NON BLONDES DEAR MR PRESIDENT 48 MAY NERVOUS WRECK 48 MAY LEATHER AND TATTOOS 48 MAY INTO THE SUN 48 MAY BIGSHOCK 48 MAY HOME BY 2 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER GOOD GIRLS 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER EVERYTHING I DIDNT SAY 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER DONT STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER AMNESIA 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER KISS ME KISS ME 50 CENT CANDY SHOP 50 CENT WINDOW SHOPPER 50 CENT IN DA CLUB 50 CENT JUST A LIL BIT 50 CENT 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT AND JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE AYO TECHNOLOGY 6400 CREW HUSTLERS REVENGE 98 DEGREES GIVE ME JUST ONE NIGHT A GREAT BIG WORLD FT CHRISTINA AGUILERA SAY SOMETHING A HA THE ALWAYS SHINES ON TV A HA THE LIVING DAYLIGHTS A LIGHTER SHADE OF BROWN ON A SUNDAY AFTERNOON -

Abstract Balance by Eva Snyder B.A

Abstract Balance By Eva Snyder B.A. Music and Computer Science Mount Holyoke College Balance, a three-song extended play album, was recorded in Nashville, Tennessee in March of 2017 and debuted during an evening length senior recital on April 15th, 2017 at Mount Holyoke College. This paper details the processes of networking, marketing, and recording I have undertaken to produce my first professional album in the country music genre. Throughout this year, I have explored entrepreneurship in a new light and seen firsthand the issues that come along with the music industry. Using strong networking skills that I have developed, I have crafted my own solutions to said roadblocks. I have utilized new apps to quickly grow a supportive fanbase and interviewed fellow artists of differing levels of success searching for advice. In addition, I have emailed, phoned and met face-to-face with industry professionals as well as produced three radio-quality original songs while working seamlessly with highly accredited engineers in Nashville. Reflecting upon this year-long adventure will provide me with useful insights as to what worked and what did not work in regards toward advancing my professional music career. In the years to come, I hope Balance will spark other recording projects and be the stepping stone for me to become a successful songwriter in Music City. 1 BALANCE Eva Snyder 2 Acknowledgments I would like to thank... My Dziadziu and Babciu for providing the music that accompanies my life My family for instilling music in me since before -

DAN KELLY's Ipod 80S PLAYLIST It's the End of The

DAN KELLY’S iPOD 80s PLAYLIST It’s The End of the 70s Cherry Bomb…The Runaways (9/76) Anarchy in the UK…Sex Pistols (12/76) X Offender…Blondie (1/77) See No Evil…Television (2/77) Police & Thieves…The Clash (3/77) Dancing the Night Away…Motors (4/77) Sound and Vision…David Bowie (4/77) Solsbury Hill…Peter Gabriel (4/77) Sheena is a Punk Rocker…Ramones (7/77) First Time…The Boys (7/77) Lust for Life…Iggy Pop (9/7D7) In the Flesh…Blondie (9/77) The Punk…Cherry Vanilla (10/77) Red Hot…Robert Gordon & Link Wray (10/77) 2-4-6-8 Motorway…Tom Robinson (11/77) Rockaway Beach…Ramones (12/77) Statue of Liberty…XTC (1/78) Psycho Killer…Talking Heads (2/78) Fan Mail…Blondie (2/78) This is Pop…XTC (3/78) Who’s Been Sleeping Here…Tuff Darts (4/78) Because the Night…Patty Smith Group (4/78) Ce Plane Pour Moi…Plastic Bertrand (4/78) Do You Wanna Dance?...Ramones (4/78) The Day the World Turned Day-Glo…X-Ray Specs (4/78) The Model…Kraftwerk (5/78) Keep Your Dreams…Suicide (5/78) Miss You…Rolling Stones (5/78) Hot Child in the City…Nick Gilder (6/78) Just What I Needed…The Cars (6/78) Pump It Up…Elvis Costello (6/78) Airport…Motors (7/78) Top of the Pops…The Rezillos (8/78) Another Girl, Another Planet…The Only Ones (8/78) All for the Love of Rock N Roll…Tuff Darts (9/78) Public Image…PIL (10/78) My Best Friend’s Girl…the Cars (10/78) Here Comes the Night…Nick Gilder (11/78) Europe Endless…Kraftwerk (11/78) Slow Motion…Ultravox (12/78) Roxanne…The Police (2/79) Lucky Number (slavic dance version)…Lene Lovich (3/79) Good Times Roll…The Cars (3/79) Dance -

Smash Hits Volume 63

35pUSA$l75 April 30 -May 13 1981 GIRLSCHOOL PAULWEILER THE FALL GET ENOUGH THE BANDS PlAY pRYNUMAN^ ADAM ECHO & THE B TEARDROP EX gjGS^ Vol. 3 No. 9 GREY DAY ON STIFF RECORDS THE LARCHES" lay bathed in the warm afternoon sunshine. Peregrine vas on the verandah, sipping a cool drink and dangling his toes in the When I get home it's late at night yping pool. Looking up from the Adam And The Ants colour portrait he I'm black and bloody from my life vatched a butterfly flit lazily from page to page, alighting briefly on the I haven't time to clean my hands ulian Cope feature before shooting off to inspect the Gary Numan Cuts will only sting me through my dreams entrespread. Somewhere in the distance he could hear the Head jardener whistling as he ran a heavy roller over the last part of The Jam It's well past midnight as I lie eries. In a semi-conscious state The only other sound to pierce the drowsy calm came from the back I dream of people fighting me age, where Samantha and Roderick were playing tennis on the Echo And Without any reason I can see he Bunnymen pin-up. Having completed his inspection of The Fall eature. Peregrine yawned and stretched. As Victoria began to rub the Chorus lirst of the tanning lotion into his back, he licked the end of his pencil and In the morning I awake Hon. ifl My arm* my lags my body aches The sky outside is wet and gray So begins another weary day GREY DAY Ma So begins another weary day CROCODILESJflio And Thj Builnymen After eating I go out KEEP OJpfvING YOU REO Speedwagon...|kga....8 People passing by ma shout this IT'SJPNG TO HAPPEN The Undertones....^A,9 I can't stand agony Why don't they talk to ma 1AGNIFICENT FIVE Adam And The Ants 15 the park I have to rest WIUDA TRIANGLE Barry Manilow....... -

Party Warehouse Karaoke & Jukebox Song List

Party Warehouse Karaoke & Jukebox Song List Please note that this is a sample song list from one Karaoke & Jukebox Machine which may vary from the one you hire You can view a sample song list for digital jukebox (which comes with the karaoke machine) below. Song# ARTIST TRACK NAME 1 10CC IM NOT IN LOVE Karaoke 2 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY Karaoke 3 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE Karaoke 4 4 NON BLONDES WHATS UP Karaoke 5 50 CENT IN DA CLUB Karaoke 6 A HA TAKE ON ME Karaoke 7 A HA THE SUN ALWAYS SHINES ON TV Karaoke 8 A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE Karaoke 9 AALIYAH I DONT WANNA Karaoke 10 ABBA DANCING QUEEN Karaoke 11 ABBA WATERLOO Karaoke 12 ABBA THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC Karaoke 13 ABBA SUPER TROUPER Karaoke 14 ABBA SOS Karaoke 15 ABBA ROCK ME Karaoke 16 ABBA MONEY MONEY MONEY Karaoke 17 ABBA MAMMA MIA Karaoke 18 ABBA KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU Karaoke 19 ABBA FERNANDO Karaoke 20 ABBA CHIQUITITA Karaoke 21 ABBA I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO Karaoke 22 ABC POISON ARROW Karaoke 23 ABC THE LOOK OF LOVE Karaoke 24 ACDC STIFF UPPER LIP Karaoke 25 ACE OF BASE ALL THAT SHE WANTS Karaoke 26 ACE OF BASE DONT TURN AROUND Karaoke 27 ACE OF BASE THE SIGN Karaoke 28 ADAM ANT ANT MUSIC Karaoke 29 AEROSMITH CRAZY Karaoke 30 AEROSMITH I DONT WANT TO MISS A THING Karaoke 31 AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR Karaoke 32 AFROMAN BECAUSE I GOT HIGH Karaoke 33 AIR SUPPLY ALL OUT OF LOVE Karaoke 34 ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW Karaoke 35 ALANIS MORISSETTE THANK U Karaoke 36 ALANIS MORISSETTE ALL I REALLY WANT Karaoke 37 ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC Karaoke 38 ALANNAH MYLES BLACK VELVET Karaoke -

DAN KELLY's Ipod 80S PLAYLIST It's the End of The

DAN KELLY’S iPOD 80s PLAYLIST It’s The End of the 70s Cherry Bomb…The Runaways (9/76) Anarchy in the UK…Sex Pistols (12/76) X Offender…Blondie (1/77) See No Evil…Television (2/77) Police & Thieves…The Clash (3/77) Dancing the Night Away…Motors (4/77) Sound and Vision…David Bowie (4/77) Solsbury Hill…Peter Gabriel (4/77) Sheena is a Punk Rocker…Ramones (7/77) First Time…The Boys (7/77) Lust for Life…Iggy Pop (9/7D7) In the Flesh…Blondie (9/77) The Punk…Cherry Vanilla (10/77) Red Hot…Robert Gordon & Link Wray (10/77) 2-4-6-8 Motorway…Tom Robinson (11/77) Rockaway Beach…Ramones (12/77) Statue of Liberty…XTC (1/78) Psycho Killer…Talking Heads (2/78) Fan Mail…Blondie (2/78) Who’s Been Sleeping Here…Tuff Darts (4/78) Because the Night…Patty Smith Group (4/78) Touch and Go…Magazine (4/78) Ce Plane Pour Moi…Plastic Bertrand (4/78) Do You Wanna Dance?...Ramones (4/78) The Day the World Turned Day-Glo…X-Ray Specs (4/78) The Model…Kraftwerk (5/78) Keep Your Dreams…Suicide (5/78) Miss You…Rolling Stones (5/78) Hot Child in the City…Nick Gilder (6/78) Just What I Needed…The Cars (6/78) Pump It Up…Elvis Costello (6/78) Sex Master…Squeeze (7/78) Surrender…Cheap Trick (7/78) Top of the Pops…The Rezillos (8/78) Another Girl, Another Planet…The Only Ones (8/78) All for the Love of Rock N Roll…Tuff Darts (9/78) Public Image…PIL (10/78) I Wanna Be Sedated (megamix)…The Ramones (10/78) My Best Friend’s Girl…the Cars (10/78) Here Comes the Night…Nick Gilder (11/78) Europe Endless…Kraftwerk (11/78) Slow Motion…Ultravox (12/78) I See Red…Split Enz (12/78) Roxanne…The -

![2000 by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 1926 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9244/2000-by-artist-no-of-tunes-1926-5209244.webp)

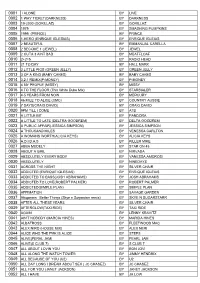

2000 by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 1926 ]

[ 2000 by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 1926 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 98 DEGREES >> GIVE ME JUST ONE MORE NIGHT A >> STARBUCKS A R RAHMAN FEAT THE PUSSYCAT DOLLS >> JAI HO - YOU ARE MY DESTINY A T B >> KILLER 2000 {K} A T C >> MY HEART BEATS LIKE A DRUM {K} A1 >> TAKE ON ME AALIYAH >> TRY AGAIN {K} AC DC >> ROCK' N ROLL TRAIN AC DC >> STIFF UPPER LIP ADAM BRAND >> BEATING AROUND THE BUSH ADAM BRAND >> BUILT FOR SPEED ADAM BRAND >> DIRT TRACK COWBOY ADAM BRAND >> GET LOUD ADAM BRAND >> I DID WHAT ADAM BRAND >> I STILL CALL AUSTRALIA HOME ADAM BRAND >> I'M GOING TO VENUS ADAM BRAND >> LIFE WILL BRING YOU HOME ADAM HARVEY >> BEAUTY'S IN THE EYE ADAM HARVEY >> BOATS TO BUILD ADAM HARVEY >> DOGHOUSE ADAM HARVEY >> GOD MADE BEER ADAM HARVEY >> I FEEL LIKE HANK WILLIAMS TONIGHT ADAM HARVEY >> I'LL DRINK TO THAT ADAM HARVEY >> LITTLE BITTY THING CALLED LOVE ADAM HARVEY >> ONE AND ONE AND ONE ADAM HARVEY >> ONE OF A KIND ADAM HARVEY >> SHE'S GONE, GONE, GONE ADAM HARVEY >> THAT'S JUST HOW SHE