The Human Version 2.0 AI, Humanoids, and Immortality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This Copy of the Thesis Has Been

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2012 Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman Vita-More, Natasha http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/1182 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognize that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. 1 Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman by NATASHA VITA-MORE A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfillment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Art & Media Faculty of Arts April 2012 2 Natasha Vita-More Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman The thesis’ study of life expansion proposes a framework for artistic, design-based approaches concerned with prolonging human life and sustaining personal identity. To delineate the topic: life expansion means increasing the length of time a person is alive and diversifying the matter in which a person exists. -

From Prometheus to Pistorius: a Genaelogy of Physical Ability

FROM PROMETHEUS TO PISTORIUS: A GENAELOGY OF PHYSICAL ABILITY by Stephanie J. Cork A thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (September, 2011) Copyright ©Stephanie J. Cork, 2011 Abstract (Fragile Frames + Monstrosities)ModernWar + (Flagged Bodies + Cyborgs)PostmodernWar = dis-AbilityCyborged ii Acknowledgements A huge thank you goes out to: my friends, colleagues, office neighbours, mentors, family, defence committee, readers, editors and Steve. Thank you, also, to the Canadian and American troops as well as Paralympic athletes, Oscar Pistorius and Aimee Mullins for their inspiration, sorry, I have borrowed your stories to perpetuate my own academic success. Thanks also to Louise Bark for her endless patience and kindness, as well as a pint (or three!) at Ben’s Pub. Anne and Wendy and especially Michelle: you are lifesavers! Finally, my eternal gratitude to the: “greatest man alive,” Dr. Rob Beamish (Scott Mason 2011). iii Table of Contents Abstract............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements......................................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents............................................................................................................................ iv Chapter 1: Introduction.....................................................................................................................1 -

Annual Report

ANNUAL Introduction | 2 REPORT Practice | 4 Deepen | 18 Financials | 27 2017 - 2018 Partners & Supporters | 28 The Laundromat Project 1 INTRODUCTION DEAR FRIENDS, How might we build an arts organization that moves with WHO WE ARE intention? How might we collaborate with artists and neighbors to facilitate lasting change? The Laundromat Project advances artists and Asking heartfelt questions, and listening deeply to voices in our community was especially gratifying in 2017 and neighbors as change agents 2018, years of transition to a new strategic vision at The Laundromat Project (The LP). Insights from our commu- in their own communities. nities in Brooklyn, Harlem, and the South Bronx informed our people-powered process as well. As the world around us shifts, we need to engage change. When the communities where we live and work are experiencing pronounced uncertainty around citi- zenship, race, and belonging, we need to reflect upon our work and reconsider our practices. We are obliged We envision a world in to ask what it means to be an organization that centers on people of color. We must interrogate our approaches which artists and neighbors to art and community as catalysts for change. Through in communities of color rigorously practicing and deepening our work, we better understand how to shape a world in which members feel work together to unleash truly connected and have the ability to influence their the power of creativity to communities in creative and effective ways. transform lives. This is where strategic visioning comes in. During this generative period, artists, neighbors, peer organizations, supporters, staff, and board weighed in on how The LP should evolve as an organization. -

Modelling User Preference for Embodied Artificial Intelligence and Appearance in Realistic Humanoid Robots

Article Modelling User Preference for Embodied Artificial Intelligence and Appearance in Realistic Humanoid Robots Carl Strathearn 1,* and Minhua Ma 2,* 1 School of Computing and Digital Technologies, Staffordshire University, Staffordshire ST4 2DE, UK 2 Falmouth University, Penryn Campus, Penryn TR10 9FE, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (M.M.) Received: 29 June 2020; Accepted: 29 July 2020; Published: 31 July 2020 Abstract: Realistic humanoid robots (RHRs) with embodied artificial intelligence (EAI) have numerous applications in society as the human face is the most natural interface for communication and the human body the most effective form for traversing the manmade areas of the planet. Thus, developing RHRs with high degrees of human-likeness provides a life-like vessel for humans to physically and naturally interact with technology in a manner insurmountable to any other form of non-biological human emulation. This study outlines a human–robot interaction (HRI) experiment employing two automated RHRs with a contrasting appearance and personality. The selective sample group employed in this study is composed of 20 individuals, categorised by age and gender for a diverse statistical analysis. Galvanic skin response, facial expression analysis, and AI analytics permitted cross-analysis of biometric and AI data with participant testimonies to reify the results. This study concludes that younger test subjects preferred HRI with a younger-looking RHR and the more senior age group with an older looking RHR. Moreover, the female test group preferred HRI with an RHR with a younger appearance and male subjects with an older looking RHR. -

A Current Status and Future Prospect of Service Robot Industry

International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-8 Issue-8S2, June 2019 A Current Status and Future Prospect of Service Robot Industry Seong-Hoon Lee, Dong-Woo Lee level abstractions(Deep Learning), which is a set of machine Abstract Background/Objectives: The robot industry has been learning algorithms that try to teach the human mind to the carrying out simple repetitive tasks in the process of machine(computer). industrialization on behalf of human beings. These robots are Recently, global IT companies such as Google and Tesla now used in more complex and diverse areas including intelligence in simple and repetitive tasks. In this study, we are focusing on developing artificial intelligence technology. describe current trends and developments in robotics industry. In November 2015, Google released an artificial intelligence Methods/Statistical analysis: Most of the tasks performed by engine called TensorFlow. In December 2015, Tesla existing robots have been performed on behalf of human beings continues to be fiercely competing with major companies to in the production site in simple and repetitive tasks. In this study, preoccupy the future AI global market, such as establishing we investigated the technology field which robot is used in more 'Open AI', a nonprofit artificial intelligence company jointly complex and diverse fields including intelligence. The trends of with WiCombinater. technology development in Japan and the United States, which are representative technologies of robot industrial technology, In the future, AI technology will be linked to 'IoT (sensor, and future prospect of robotic industry was examined. data acquisition) - wireless communication (transmission) - Findings: Intel's Robotics strategy, which Jimmy has big data, deep learning (analysis) - artificial intelligence - unveiled at Intel, is to build Jimmy as a robot platform and open product reflection'. -

The-Future-Of-Immortality-Remaking-Life

The Future of Immortality Princeton Studies in Culture and Technology Tom Boellstorff and Bill Maurer, Series Editors This series presents innovative work that extends classic ethnographic methods and questions into areas of pressing interest in technology and economics. It explores the varied ways new technologies combine with older technologies and cultural understandings to shape novel forms of subjectivity, embodiment, knowledge, place, and community. By doing so, the series demonstrates the relevance of anthropological inquiry to emerging forms of digital culture in the broadest sense. Sounding the Limits of Life: Essays in the Anthropology of Biology and Beyond by Stefan Helmreich with contributions from Sophia Roosth and Michele Friedner Digital Keywords: A Vocabulary of Information Society and Culture edited by Benjamin Peters Democracy’s Infrastructure: Techno- Politics and Protest after Apartheid by Antina von Schnitzler Everyday Sectarianism in Urban Lebanon: Infrastructures, Public Services, and Power by Joanne Randa Nucho Disruptive Fixation: School Reform and the Pitfalls of Techno- Idealism by Christo Sims Biomedical Odysseys: Fetal Cell Experiments from Cyberspace to China by Priscilla Song Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming by T. L. Taylor Chasing Innovation: Making Entrepreneurial Citizens in Modern India by Lilly Irani The Future of Immortality: Remaking Life and Death in Contemporary Russia by Anya Bernstein The Future of Immortality Remaking Life and Death in Contemporary Russia Anya Bernstein -

Are You There, God? It's I, Robot: Examining The

ARE YOU THERE, GOD? IT’S I, ROBOT: EXAMINING THE HUMANITY OF ANDROIDS AND CYBORGS THROUGH YOUNG ADULT FICTION BY EMILY ANSUSINHA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Bioethics May 2014 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Nancy King, J.D., Advisor Michael Hyde, Ph.D., Chair Kevin Jung, Ph.D. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to give a very large thank you to my adviser, Nancy King, for her patience and encouragement during the writing process. Thanks also go to Michael Hyde and Kevin Jung for serving on my committee and to all the faculty and staff at the Wake Forest Center for Bioethics, Health, and Society. Being a part of the Bioethics program at Wake Forest has been a truly rewarding experience. A special thank you to Katherine Pinard and McIntyre’s Books; this thesis would not have been possible without her book recommendations and donations. I would also like to thank my family for their continued support in all my academic pursuits. Last but not least, thank you to Professor Mohammad Khalil for changing the course of my academic career by introducing me to the Bioethics field. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures ................................................................................... iv List of Abbreviations ............................................................................................. iv Abstract ................................................................................................................ -

Company Overview

Company Overview Hanson Robotics develops the world’s most humanlike robots, endowed with remarkable expressiveness, aesthetics and interactivity. The Company and its founder, Dr. David Hanson, has built a worldwide reputation for creating robots that look and act genuinely alive, and produced many renowned robots that have received massive media and public acclaim. The lifelike appearance and behavior of the Company’s robots spring from a unique combination of robotic technology, skin technology, character design/animation, and AI. The patented nanotech skin closely resembles human skin in its feel and flexibility. Proprietary motor control systems enable Hanson robots to persuasively convey a full range of human emotions. The Company’s AI will ingest emotional, conversational, and visual data that will spawn uniquely rich insights into how people think and feel. The Company’s mission is to develop empathetic, smart living machines that will learn from human interaction and establish trusted relationships with people. These robots will teach, serve, provide comforting companionships, and through these interactions dramatically improve people’s lives. The Company envisions that one day these super-benevolent and super-intelligent machines will help us solve some of the most challenging problems of our times. One of the robot characters that the company has recently unveiled is Sophia, which is a celebrated global personality. Sophia is the most endearing, expressive, and empathetic robot that the world has ever seen. Her charm will initially stem from her incredible human likeness, unbelievable facial expressions, and verbal and nonverbal interactivity. Over time, her growing intelligence, charismatic personality, and remarkable story will enchant the world and connect with people regardless of age, gender, and culture © 2017 Hanson Robotics Limited Page 1 Commercial Applications The Company aims to radically disrupt the consumer and commercial robotics market with affordable robots that have high-quality expressions and verbal and nonverbal interactivity. -

Robot Citizenship and Women's Rights: the Case of Sophia the Robot in Saudi Arabia

Robot citizenship and women's rights: the case of Sophia the robot in Saudi Arabia Joana Vilela Fernandes Master in International Studies Supervisor: PhD, Giulia Daniele, Integrated Researcher and Guest Assistant Professor Center for International Studies, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (CEI-IUL) September 2020 Robot citizenship and women's rights: the case of Sophia the robot in Saudi Arabia Joana Vilela Fernandes Master in International Studies Supervisor: PhD, Giulia Daniele, Integrated Researcher and Guest Assistant Professor Center for International Studies, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (CEI-IUL) September 2020 Acknowledgments I would like to express my great appreciation to my parents and to my sister for the continuous moral support and motivation given during my entire studies and especially during quarantine as well as the still ongoing pandemic. I am also particularly grateful to my supervisor, Giulia Daniele, for all the provided assistance, fundamental advice, kindness and readiness to help throughout the research and writing process of my thesis. v vi Resumo Em 2017, a Arábia Saudita declarou Sophia, um robô humanoide, como cidadão Saudita oficial. Esta decisão voltou a realçar os problemas de desigualdade de género no país e levou a várias discussões relativamente a direitos das mulheres, já que o Reino é conhecido por ainda ser um país conservativo e tradicionalmente patriarcal, ter fortes valores religiosos e continuar a não tratar as mulheres de forma igualitária. Por outras palavras, este caso é particularmente paradoxal por causa da negação ativa de direitos humanos às mulheres, da sua falta de plena cidadania e da concessão simultânea deste estatuto a um ser não humano com aparência feminina. -

Download Our Press

We bring robots to life. Hanson Robotics is an AI and robotics company dedicated to creating socially intelligent machines that enrich the quality of our lives. Our innovations in AI research, robotics engineering, experiential design, storytelling and material science bring our robots to life as engaging characters, useful products and as evolving AI. Our robots will serve as AI platforms for research, education, medical and healthcare, sales and service, and entertainment applications. In time, we hope our robots will come to understand and care about us through cultivating meaningful relationships with those whose lives they touch, and evolve into wise living machines who advance civilization and achieve ever-greater good for all. www.hansonrobotics.com Press Information Follow @hansonrobotics Facebook Twitter Instagram LinkedIn YouTube Sophia is Hanson Robotics’ latest human-like robot, created by combining our innovations in science, engi- neering and artistry. She is a personication of our dreams for the future of AI, as well as a framework for Sophia’s Page advanced AI and robotics research, and an agent for Follow @realsophiarobot exploring human-robot experience in service and Facebook entertainment applications. Twitter Instagram Sophia was created to be a research platform for Hanson Robot- YouTube ics' ongoing AI and robotics research work. Working with labs, universities and companies around the world, she is an architec- ture and a platform for the development of real AI applications. The Sophia character is also an evolving science fiction character we use to help explore the future of AI and lifelike humanoids, and to engage the public in the discussion of these issues. -

Free Organizing, but Yeah

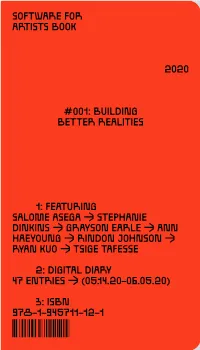

Salome Asega is an artist and researcher Rindon Johnson is an artist and writer. based in Brooklyn, NY. Salome has His most recent virtual reality film, Meat participated in residencies and fellow- Growers: A Love Story, was commis- SOFTWARE FOR ships with Eyebeam, New Museum, The sioned by Rhizome and Tentacular. Laundromat Project, and Recess. She Johnson has read, exhibited, and lec- has exhibited at the Shanghai Biennale, tured internationally. He is the author of ARTISTS BOOK MoMA, Carnegie Library, August Wilson Nobody Sleeps Better Than White People ©2020. Edited by Willa Köerner. Published on the Center, Knockdown Center, and more. (Inpatient, 2016), the VR book, Meet in the She has also given presentations and Corner (Publishing-House.Me, 2017) and occasion of Software for Artists Day 6, by Pioneer lectures at Performa, EYEO, Brooklyn Shade the King (Capricious, 2017). He Works Press in collaboration with The Creative Museum, MIT Media Lab, and more. lives in Berlin where he is an Associate Salome is currently a Ford Foundation Fellow at the Universität der Künste Independent & Are.na. Technology Fellow landscaping new Berlin. He studies VR. media arts infrastructure. She is also the Director of Partnerships at POWRPLNT, Ryan Kuo is a New York City-based artist a digital art collaboratory in Brooklyn. whose process-based and diagram- Salome received her MFA from Parsons matic works often invoke a person or at The New School in Design and people arguing. This is not to state an Technology where she also teaches. argument about a thing, but to be caught in a state of argument. -

Download Full CV

[email protected] Stephanie Dinkins www.stephaniedinkins.com Select Solo Exhibitions Conversations with Bina48, Gallatin Gallery, New York University, February 2018 Who R Ur Ppl? Harvestworks, New York, NY, December 2017 Project al-Khwarizmi (PAK) Pop UP (Solo Exhibition + Workshop Series) Recess Assembly, Brooklyn, NY, Sept – Dec 2017 This Land Is My Land, University Art Gallery, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, September. 2009 Select Projects, & Installations Not the Only One, (2018 - ), an ongoing iterative project that tells the multigenerational story of my black American family as told by a voice interactive, artificial intelligence. Project al-Khwarizmi (PAK) ongoing workshops, 2017 - Conversations with Bina48, ongoing series of video conversations with Bina48 an advanced social robot, 2014 – This Land Is My Land, University Art Gallery, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, 2009 Americana I, site-specific installation for the Carriage House Projects ’07, Islip Art Museum, Islip NY, 2007 OneOneFullBasket for Jamaica Flux 2007, site-specific installation North Fork Bank, Jamaica Queens, 2007 The End is the Beginning but Lies Far Ahead, #III, site-inspired installation for Survive/Thrive/Alive, Glyndor Gallery, Wave Hill, Bronx, NY, 2006 Select Group Exhibitions 2020 Uncanny Valley, De Young Museum, San Francisco, CA, February 22 – October 25 Virtual Beings, Transfer Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, January - February In Real Life, Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, IL, January 16 -Mar 22 The Question