Quaternary Cliff-Dwelling Bovids (Capra, Rupicapra, Hemitragus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alpine Ibex, Capra Ibex

(CAPRA IBEX) ALPINE IBEX by: Braden Stremcha EVOLUTION Alpine ibex is part of the Bovidae family under the order Artiodactyla. The Capra genus signifies this species specifically as a wild goat, but this genus shares very similar evolutionary features as species we recognize in Montana like Oreamnos (mountain goat) and Ovis (sheep). Capra, Oreamnos, and Ovis most likely derived in evolution from each other due to glacial migration and failure to hybridize between genera and species.Capra ibex was first historically observed throughout the central Alpine Range of Europe, then was decreased to Grand Paradiso National Park in Italy and the Maurienne Valley in France but has since been reintroduced in multiple other countries across the Alps. FORM AND FUNCTION Capra ibex shares a typical hoofed unguligrade foot posture, a cannon bone with raised calcaneus, and the common cursorial locomotion associated with species in Artiodactyla. These features allow the alpine ibex to maneuver through the steep terrain in which they reside. Specifically, for alpine ungulates and the alpine ibex, more energy is put into balance and strength to stay on uneven terrain than moving long distances. Alpine ibexes are often observed climbing artificial dams that are almost vertical to lick mineral deposits! This example shows how efficient Capra ibex is at navigating steep and dangerous terrain. The most visual distinction that sets the Capra genus apart from others is the large, elongated semicircular horns. Alpine ibex specifically has horns that grow throughout their life span at an average of 80mm per year in males. When winter comes around this growth is stunted until spring and creates an obvious ring on the horn that signifies that year’s overall growth. -

Experimentation Preceding Innovation in a MIS5 Pre-Still Bay Layer from Diepkloof Rock Shelter (South Africa): Emerging Technologies and Symbols

RESEARCH ARTICLE Experimentation preceding innovation in a MIS5 Pre-Still Bay layer from Diepkloof Rock Shelter (South Africa): emerging technologies and symbols. Guillaume Porraz1,2, John E. Parkington3, Patrick Schmidt4,5, Gérald Bereiziat6, Jean-Philip Brugal1, Laure Dayet7, Marina Igreja8, Christopher E. Miller9,10, Viola C. Schmid4,11, Chantal Tribolo12,, Aurore 4,2 13 1 Cite as: Porraz, G., Parkington, J. E., Val , Christine Verna , Pierre-Jean Texier Schmidt, P., Bereiziat, G., Brugal, J.- P., Dayet, L., Igreja, M., Miller, C. E., Schmid, V. C., Tribolo, C., Val, A., Verna, C., Texier, P.-J. (2020). 1 Experimentation preceding Aix Marseille Université, CNRS, Ministère de la Culture, UMR 7269 Lampea, 5 rue du Château innovation in a MIS5 Pre-Still Bay de l’Horloge, F-13094 Aix-en-Provence, France layer from Diepkloof Rock Shelter 2 University of the Witwatersrand, Evolutionary Studies Institute, Johannesburg, South Africa (South Africa): emerging 3 technologies and symbols. University of Cape Town, Department of Archaeology, Cape Town, South Africa EcoEvoRxiv, ch53r, ver. 3 peer- 4 Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen, Department of Early Prehistory and Quaternary reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology, Schloss Hohentübingen, 72070 Tübingen, Germany Archaeology. doi: 5 10.32942/osf.io/ch53r Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen, Department of Geosciences, Applied Mineralogy, Wilhelmstraße 56, 72074 Tübingen, Germany. 6 Université de Bordeaux, UMR CNRS 5199 PACEA, F-33615 Pessac, France Posted: 2020-12-17 7 CNRS-Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, UMR 5608 TRACES, F-31058 Toulouse, France 8 LARC DGPC, Ministry of Culture (Portugal) / ENVARCH Cibio-Inbio 9 Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen, Institute for Archaeological Sciences & Senckenberg Recommender: Anne Delagnes Center for Human Evolution and Paleoenvironment, Rümelinstr. -

Foot and Mouth Disease Fastfact

Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) What is foot and mouth How does FMD affect my Who should I contact if I disease and what causes it? animal? suspect FMD? Foot and mouth disease (FMD) is The most common signs of foot Contact your veterinarian a highly contagious viral disease of and mouth disease are fever and immediately. FMD is not currently cloven-hoofed (two-toed) animals (e.g., the formation of blisters, ulcers and found in the United States; suspicion cattle, pigs, sheep). FMD causes painful sores on the mouth, tongue, nose, of the disease requires immediate sores and blisters on the feet, mouth feet, and teats. Foot lesions occur in attention. the area of the coronary band and and teats of animals. between the toes. Infected cattle are How can I protect my animal Foot and mouth disease is a high depressed, reluctant to move, and from FMD? consequence livestock disease due to unwilling or unable to eat, which can To prevent the introduction of FMD, its potential for rapid spread, severe lead to decreased milk production, use strict biosecurity procedures on trade restrictions and the subsequent weight loss, and poor growth. Affected your farm. Isolate any new introductions economic impacts that would result. animals may also have nasal discharge or animal returning to the farm for The disease occurs in parts of Asia, and excessive salivation. Pigs often several weeks before introducing them have sore feet but less commonly into the herd. Minimize visitors on Africa, the Middle East and South develop mouth lesions. Sheep and your farm, especially those that have America, but has been eradicated goats show very mild, if any, signs of traveled from countries with FMD. -

Extinction of Harrington's Mountain Goat (Vertebrate Paleontology/Radiocarbon/Grand Canyon) JIM I

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 83, pp. 836-839, February 1986 Geology Extinction of Harrington's mountain goat (vertebrate paleontology/radiocarbon/Grand Canyon) JIM I. MEAD*, PAUL S. MARTINt, ROBERT C. EULERt, AUSTIN LONGt, A. J. T. JULL§, LAURENCE J. TOOLIN§, DOUGLAS J. DONAHUE§, AND T. W. LINICK§ *Department of Geology, Northern Arizona University, and Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff, AZ 86011; tDepartment of Geosciences and tArizona State Museum and Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721; §National Science Foundation Accelerator Facility for Radioisotope Analysis, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721 Communicated by Edward S. Deevey, Jr., October 7, 1985 ABSTRACT Keratinous horn sheaths of the extinct Har- rington's mountain goat, Oreamnos harringtoni, were recov- ered at or near the surface of dry caves of the Grand Canyon, Arizona. Twenty-three separate specimens from two caves were dated nondestructively by the tandem accelerator mass spectrometer (TAMS). Both the TAMS and the conventional dates indicate that Harrington's mountain goat occupied the Grand Canyon for at least 19,000 years prior to becoming extinct by 11,160 + 125 radiocarbon years before present. The youngest average radiocarbon dates on Shasta ground sloths, Nothrotheriops shastensis, from the region are not significantly younger than those on extinct mountain goats. Rather than sequential extinction with Harrington's mountain goat disap- pearing from the Grand Canyon before the ground sloths, as one might predict in view ofevidence ofclimatic warming at the time, the losses were concurrent. Both extinctions coincide with the regional arrival of Clovis hunters. Certain dry caves of arid America have yielded unusual perishable remains of extinct Pleistocene animals, such as hair, dung, and soft tissue of extinct ground sloths (1) and, recently, ofmammoths (2). -

An Analysis of the Phylogenetic Relationship of Thai Cervids Inferred from Nucleotide Sequences of Protein Kinase C Iota (PRKCI) Intron

Kasetsart J. (Nat. Sci.) 43 : 709 - 719 (2009) An Analysis of the Phylogenetic Relationship of Thai Cervids Inferred from Nucleotide Sequences of Protein Kinase C Iota (PRKCI) Intron Kanita Ouithavon1, Naris Bhumpakphan2, Jessada Denduangboripant3, Boripat Siriaroonrat4 and Savitr Trakulnaleamsai5* ABSTRACT The phylogenetic relationship of five Thai cervid species (n=21) and four spotted deer (Axis axis, n=4), was determined based on nucleotide sequences of the intron region of the protein kinase C iota (PRKCI) gene. Blood samples were collected from seven captive breeding centers in Thailand from which whole genomic DNA was extracted. Intron1 sequences of the PRKCI nuclear gene were amplified by a polymerase chain reaction, using L748 and U26 primers. Approximately 552 base pairs of all amplified fragments were analyzed using the neighbor-joining distance matrix method, and 19 parsimony- informative sites were analyzed using the maximum parsimony approach. Phylogenetic analyses using the subfamily Muntiacinae as outgroups for tree rooting indicated similar topologies for both phylogenetic trees, clearly showing a separation of three distinct genera of Thai cervids: Muntiacus, Cervus, and Axis. The study also found that a phylogenetic relationship within the genus Axis would be monophyletic if both spotted deer and hog deer were included. Hog deer have been conventionally classified in the genus Cervus (Cervus porcinus), but this finding supports a recommendation to reclassify hog deer in the genus Axis. Key words: Thailand, the family Cervidae, protein kinase C iota (PRKCI) intron, phylogenetic tree, taxonomy INTRODUCTION 1987; Gentry, 1994). Cervids, or what is commonly called “deer,” are mostly characterized The family Cervidae is one of the most by antlers with a bony inner core and velvet skin specious families of artiodactyls, with an extensive cover. -

Kosti: Jedna Od Najranijih Sekundarnih Sirovina Selena Vitezović

Kosti: jedna od najranijih sekundarnih sirovina Selena Vitezović DOI: 10.17234/9789531757232-03 Uvod Recikliranje i ponovna uporaba raznih materijala i predmeta javljaju se kroz cijelu ljudsku po- vijest, još od samih početaka (Amick 2015). Međutim, odnos prema praksi recikliranja dosta se mijenjao tijekom vremena i u različitim kulturama. U novije vrijeme recikliranje i ponovna uporaba prošli su kroz nagle i drastične promjene, prvo s industrijskom revolucijom, naglim povećanjem proizvodnje i stvaranjem „potrošačkog društva”, a potom, posljednjih desetljeća, s rastućom svijesti o neophodnosti zaštite okoliša i održivosti resursa (Cooper 2008; Amick - 2015: 4-5). - Recikliranje i ponovna uporaba često se vezuju za nedostatak i štednju (vremena, truda, ma- terijala itd.), osobito iz današnje perspektive, gdje se prikupljanjem sekundarnih sirovina naj češće bave najsiromašniji slojevi društva ili ekonomski vrlo siromašne zemlje. I arheološki do kumentirani primjeri ponovne uporabe često se interpretiraju kroz prizmu današnjeg pogleda,- odnosno kao odraz štednje i ekonomske isplativosti. Razlozi i motivi za recikliranje u različitim kulturama, međutim, nisu bili samo ekonomski, već i kulturni, odražavajući kulturni odnos pre ma određenim predmetima i sirovinama od kojih su nastali (cf. Drackner 2005; Amick 2015). - Arheološki primjeri reciklaže i ponovne uporabe u različitim društvima brojni su i raznovrsni.- Najuočljiviji su primjeri koji se odnose na sekundarno korištenje građevinskoget al. materijala (Bar ker 2010; 2015), kao i u slučajevima -

Favourableness and Connectivity of a Western Iberian Landscape for the Reintroduction of the Iconic Iberian Ibex Capra Pyrenaica

Favourableness and connectivity of a Western Iberian landscape for the reintroduction of the iconic Iberian ibex Capra pyrenaica R ITA T. TORRES,JOÃO C ARVALHO,EMMANUEL S ERRANO,WOUTER H ELMER P ELAYO A CEVEDO and C ARLOS F ONSECA Abstract Traditional land use practices declined through- Keywords Capra pyrenaica, environmental favourableness, out many of Europe’s rural landscapes during the th cen- graph theory, habitat connectivity, Iberian ibex, reintroduc- tury. Rewilding (i.e. restoring ecosystem functioning with tion, ungulate minimal human intervention) is being pursued in many areas, and restocking or reintroduction of key species is often part of the rewilding strategy. Such programmes re- Introduction quire ecological information about the target areas but this is not always available. Using the example of the an has shaped landscapes for centuries (Vos & Iberian ibex Capra pyrenaica within the Rewilding Europe Meekes, ). In the last decades socio-economic M framework we address the following questions: ( ) Are and lifestyle changes have driven a rural exodus and the there areas in Western Iberia that are environmentally fa- abandonment of land throughout many of Europe’s rural vourable for reintroduction of the species? ( ) If so, are landscapes (MacDonald et al., ; Höchtl et al., ). these areas well connected with each other? ( ) Which of In some cases sociocultural and economic problems have these areas favour the establishment and expansion of a vi- created new opportunities for conservation (Theil et al., ). able population -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

Capture, Restraint and Transport Stress in Southern Chamois (Rupicapra Pyrenaica)

Capture,Capture, restraintrestraint andand transporttransport stressstress ininin SouthernSouthern chamoischamois ((RupicapraRupicapra pyrenaicapyrenaica)) ModulationModulation withwith acepromazineacepromazine andand evaluationevaluation usingusingusing physiologicalphysiologicalphysiological parametersparametersparameters JorgeJorgeJorge RamónRamónRamón LópezLópezLópez OlveraOlveraOlvera 200420042004 Capture, restraint and transport stress in Southern chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica) Modulation with acepromazine and evaluation using physiological parameters Jorge Ramón López Olvera Bellaterra 2004 Esta tesis doctoral fue realizada gracias a la financiación de la Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología (proyecto CICYT AGF99- 0763-C02) y a una beca predoctoral de Formación de Investigadores de la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, y contó con el apoyo del Departament de Medi Ambient de la Generalitat de Catalunya. Los Doctores SANTIAGO LAVÍN GONZÁLEZ e IGNASI MARCO SÁNCHEZ, Catedrático de Universidad y Profesor Titular del Área de Conocimiento de Medicina y Cirugía Animal de la Facultad de Veterinaria de la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, respectivamente, CERTIFICAN: Que la memoria titulada ‘Capture, restraint and transport stress in Southern chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica). Modulation with acepromazine and evaluation using physiological parameters’, presentada por el licenciado Don JORGE R. LÓPEZ OLVERA para la obtención del grado de Doctor en Veterinaria, se ha realizado bajo nuestra dirección y, considerándola satisfactoriamente -

Anaplasma Phagocytophilum and Babesia Species Of

pathogens Article Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia Species of Sympatric Roe Deer (Capreolus capreolus), Fallow Deer (Dama dama), Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) and Red Deer (Cervus elaphus) in Germany Cornelia Silaghi 1,2,*, Julia Fröhlich 1, Hubert Reindl 3, Dietmar Hamel 4 and Steffen Rehbein 4 1 Institute of Comparative Tropical Medicine and Parasitology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Leopoldstr. 5, 80802 Munich, Germany; [email protected] 2 Institute of Infectology, Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, Südufer 10, 17493 Greifswald Insel Riems, Germany 3 Tierärztliche Fachpraxis für Kleintiere, Schießtrath 12, 92709 Moosbach, Germany; [email protected] 4 Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica GmbH, Kathrinenhof Research Center, Walchenseestr. 8-12, 83101 Rohrdorf, Germany; [email protected] (D.H.); steff[email protected] (S.R.) * Correspondence: cornelia.silaghi@fli.de; Tel.: +49-0-383-5171-172 Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 18 November 2020; Published: 20 November 2020 Abstract: (1) Background: Wild cervids play an important role in transmission cycles of tick-borne pathogens; however, investigations of tick-borne pathogens in sika deer in Germany are lacking. (2) Methods: Spleen tissue of 74 sympatric wild cervids (30 roe deer, 7 fallow deer, 22 sika deer, 15 red deer) and of 27 red deer from a farm from southeastern Germany were analyzed by molecular methods for the presence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia species. (3) Results: Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia DNA was demonstrated in 90.5% and 47.3% of the 74 combined wild cervids and 14.8% and 18.5% of the farmed deer, respectively. Twelve 16S rRNA variants of A. phagocytophilum were delineated. -

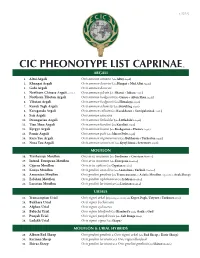

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

Dama Dama. by George A

MAMMALIAN SPECIES No. 317, pp. 1-8,3 figs. Dama dama. By George A. Feldharner, Kelly C. Farris-Renner, and Celeste M. Barker Published 27 December 1988 by The American Society of Mammalogists Dama dama (Linnaeus, 1758) Detailed descripti ons of the skull and dentition of European fallow deer are in Flerov (19 52), and Harrison (1968) described Persian Fallow Deer fallow deer. Cercus dum a Linnaeus, 1758 :67. T ype locality Sweden (introduced). Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mspecies/article/doi/10.2307/3504141/2600626 by guest on 29 September 2021 Ty pe spec ies of Duma Frisch. 1775 validated by plenary GENERAL CHARACTERS. Pelage coloration is the most powers. var iable of any spec ies of deer, with four main color varieties: white. Plat vccros plinii Zimmer ma n, 1780: 129. Renamin g of duma. men il, common (typical), and black (Chapm an and Chapm an. 1975). Cercus platvccros G. Cuvier , 1798:160. Renaming of dama. Int ermediat e pelage colors are cream. sandy , silver-grey, and sooty C NI'IIS mauricus F. Cuvier, 18 16:72. No localit y given. (Whitehead. 1972). Typical pelage is darker on the dorsal surface Ccr ru s (I)ama) m esopot amicus Brooke. 1875:26 4. Type localit y than the ventral sur face . ches t. and lower legs. A black dor sal stripe Khuzistan, Luristan (Persia). Ir an . ext end s from the na pe of the neck to the tip of the tail and around the upper edge of the white rump patch. T ypically. white spots are CONTEXT AND CONTENT.