Enteric Peripheral Neuroblastoma in a Calf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California Tumor Tissue Registry Eighty-Eighth Semi

CALIFORN IA TUMOR TISSUE REGISTRY EIGHTY-EIGHTH SEMI -ANNUAL SLIDE SEMINAR ON TUMORS OF THE CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM MODERATOR: BERN W. SCHti THAUER, M. D. HEAD SECTION OF SURGICAL PATHOLOGY MAYO CLINIC PROFESSOR OF PATHOLOGY ROCHESTER, MINNESOTA CHAIRMAN: PHILIP VAN HALE, M. D. ASSOCIATE PATHOLOGIST HUNTINGTON MEMORIAL HOSP ITAL PASADENA, CALIFORNIA SUNDAY - JUNE 3, 1990 9:00 A.M. - 5:00 P.M. REGISTRATION: 7:30 A.M. SHERATON PLAZA LA REINA ~OTEL LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA (213) 642-1111 Please bring your protocol, but do not bring slides or microscopes to the meeting. CONTRIBUTOR: Bernd W. Scheithauer, M. 0. JUNE 1990 - CASE NO. 1 Rochester, Minnesota TISSUE FROM: Brain, left temporal parietal lobe ACCESSION NO. 26731 CLINICAL ABSTRACT : The patient is a 46 -year-old white ma le wh o experienced a head injury in 1960 but had no history of neurologic disturbances until 1982 at which time he noted the sudden onset of expressive aphasia. CT scan demonstrated a hypodense left temporoparietal lesion associated with a cyst. No enhancement was seen. - The patient elected to be medically observed over a five year interval, there being no intervention until symptoms interfered with his lifestyle. During that time he was maintained on phenobabital. The frequen cy of his partial complex seizures, which were characterized by expressive more than receptive aphasia, varied from one per month to six per week. They lasted from 1 to 30 minutes. No sensorimotor component was ever observed. Memory deficits followed the episodes. The first evidence of tumor enhancement was noted in 1984 and was seen to be somewhat more extensive in a 1986 study. -

A Molecular Target for Human Glioblastoma

Kuan et al. BMC Cancer 2010, 10:468 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/10/468 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access MRP3: a molecular target for human glioblastoma multiforme immunotherapy Chien-Tsun Kuan1,2*†, Kenji Wakiya1,2†, James E Herndon II2, Eric S Lipp2, Charles N Pegram1,2, Gregory J Riggins3, Ahmed Rasheed1, Scott E Szafranski1, Roger E McLendon1,2, Carol J Wikstrand4, Darell D Bigner1,2* Abstract Background: Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is refractory to conventional therapies. To overcome the problem of heterogeneity, more brain tumor markers are required for prognosis and targeted therapy. We have identified and validated a promising molecular therapeutic target that is expressed by GBM: human multidrug-resistance protein 3 (MRP3). Methods: We investigated MRP3 by genetic and immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of human gliomas to determine the incidence, distribution, and localization of MRP3 antigens in GBM and their potential correlation with survival. To determine MRP3 mRNA transcript and protein expression levels, we performed quantitative RT-PCR, raising MRP3-specific antibodies, and IHC analysis with biopsies of newly diagnosed GBM patients. We used univariate and multivariate analyses to assess the correlation of RNA expression and IHC of MRP3 with patient survival, with and without adjustment for age, extent of resection, and KPS. Results: Real-time PCR results from 67 GBM biopsies indicated that 59/67 (88%) samples highly expressed MRP3 mRNA transcripts, in contrast with minimal expression in normal brain samples. Rabbit polyvalent and murine monoclonal antibodies generated against an extracellular span of MRP3 protein demonstrated reactivity with defined MRP3-expressing cell lines and GBM patient biopsies by Western blotting and FACS analyses, the latter establishing cell surface MRP3 protein expression. -

Abnormality of the Middle Phalanx of the 4Th Toe Abnormality of The

Glucocortocoid-insensitive primary hyperaldosteronism Absence of alpha granules Dexamethasone-suppresible primary hyperaldosteronism Abnormal number of alpha granules Primary hyperaldosteronism Nasogastric tube feeding in infancy Abnormal alpha granule content Poor suck Nasal regurgitation Gastrostomy tube feeding in infancy Abnormal alpha granule distribution Lumbar interpedicular narrowing Secondary hyperaldosteronism Abnormal number of dense granules Abnormal denseAbnormal granule content alpha granules Feeding difficulties in infancy Primary hypercorticolismSecondary hypercorticolism Hypoplastic L5 vertebral pedicle Caudal interpedicular narrowing Hyperaldosteronism Projectile vomiting Abnormal dense granules Episodic vomiting Lower thoracicThoracolumbar interpediculate interpediculate narrowness narrowness Hypercortisolism Chronic diarrhea Intermittent diarrhea Delayed self-feeding during toddler Hypoplastic vertebral pedicle years Intractable diarrhea Corticotropin-releasing hormone Protracted diarrhea Enlarged vertebral pedicles Vomiting Secretory diarrhea (CRH) deficient Adrenocorticotropinadrenal insufficiency (ACTH) Semantic dementia receptor (ACTHR) defect Hypoaldosteronism Narrow vertebral interpedicular Adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) distance Hypocortisolemia deficient adrenal insufficiency Crohn's disease Abnormal platelet granules Ulcerative colitis Patchy atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium Corticotropin-releasing hormone Chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis Single isolated congenital Nausea Diarrhea Hyperactive bowel -

Sinonasal Tumors

Prepared by Kurt Schaberg Sinonasal/Nasopharyngeal Tumors Benign Sinonasal Papillomas aka Schneiderian papilloma Morphology Location Risk of Molecular transformation Exophytic Exophytic growth; Nasal Very low risk Low-risk HPV immature squamous epithelium septum subtypes Inverted Inverted ‘‘ribbonlike’’ growth; Lateral Low to EGFR immature squamous epithelium; wall and Intermediate risk mutations or transmigrating intraepithelial sinuses low-risk HPV neutrophilic inflammation subtypes Oncocytic Exophytic and endophytic growth; Lateral Low to KRAS multilayered oncocytic epithelium; wall and intermediate microcysts and intraepithelial sinuses neutrophilic microabscesses Modified from: Weindorf et al. Arch Pathol Lab Med—Vol 143, November 2019 Oncocytic Sinonasal Papilloma Note the abundant oncocytic epithelium with numerous neutrophils Inverted Sinonasal Papilloma Note the inverted, “ribbon-like” growth Respiratory Epithelial Adenomatoid Hamartoma aka “REAH” Sinonasal glandular proliferation arising from the surface epithelium (i.e., in continuity with the surface). Invaginations of small to medium-sized glands surrounded by hyalinized stroma with characteristic thickened, eosinophilic basement membrane Exists on a spectrum with seromucinous hamartoma, which has smaller glands. Should be able to draw a circle around all of the glands though, if too confluent → consider a low-grade adenocarcinoma Inflammatory Polyp Surface ciliated, sinonasal mucosa, possibly with squamous metaplasia. Edematous stroma (without a proliferation of seromucinous glands). Mixed inflammation (usu. Lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils) Pituitary adenoma Benign anterior pituitary tumor Although usually primary to sphenoid bone, can erode into nasopharynx or be ectopic Can result in endocrine disorders, such as Cushing’s disease or acromegaly. Solid, nested, or trabecular growth of epithelioid cells with round nuclei and speckled chromatin and eosinophilic, granular chromatin. Express CK, and neuroendocrine markers. -

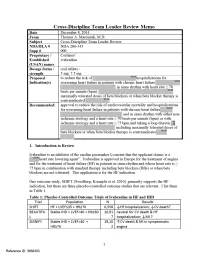

Statistical Analysis Plan

Cover Page for Statistical Analysis Plan Sponsor name: Novo Nordisk A/S NCT number NCT03061214 Sponsor trial ID: NN9535-4114 Official title of study: SUSTAINTM CHINA - Efficacy and safety of semaglutide once-weekly versus sitagliptin once-daily as add-on to metformin in subjects with type 2 diabetes Document date: 22 August 2019 Semaglutide s.c (Ozempic®) Date: 22 August 2019 Novo Nordisk Trial ID: NN9535-4114 Version: 1.0 CONFIDENTIAL Clinical Trial Report Status: Final Appendix 16.1.9 16.1.9 Documentation of statistical methods List of contents Statistical analysis plan...................................................................................................................... /LQN Statistical documentation................................................................................................................... /LQN Redacted VWDWLVWLFDODQDO\VLVSODQ Includes redaction of personal identifiable information only. Statistical Analysis Plan Date: 28 May 2019 Novo Nordisk Trial ID: NN9535-4114 Version: 1.0 CONFIDENTIAL UTN:U1111-1149-0432 Status: Final EudraCT No.:NA Page: 1 of 30 Statistical Analysis Plan Trial ID: NN9535-4114 Efficacy and safety of semaglutide once-weekly versus sitagliptin once-daily as add-on to metformin in subjects with type 2 diabetes Author Biostatistics Semaglutide s.c. This confidential document is the property of Novo Nordisk. No unpublished information contained herein may be disclosed without prior written approval from Novo Nordisk. Access to this document must be restricted to relevant parties.This -

Cerebellar Liponeurocytoma Sreedhar Babu Et Al Case Report: Cerebellar Liponeurocytoma: a Case-Report

Cerebellar liponeurocytoma Sreedhar Babu et al Case Report: Cerebellar liponeurocytoma: a case-report K.V. Sreedhar Babu,1 A.K. Chowhan,2 N. Rukmangadha,2 B.C.M. Prasad,3 M. Kumaraswamy Reddy2 Departments of 1Immuno Haematology & Blood Transfusion, 2Pathology and 3Neurosurgery, Sri Venkateswara Institute of Medical Sciences, Tirupati ABSTRACT Cerebellar liponeurocytoma is a rare cerebellar neoplasm of adults with advanced neuronal / neurocytic and focal lipomatous differentiation, a low proliferative potential and a favorable clinical prognosis corresponding to World Health Organization grade I or II. Only a few cases have been described in the literature (approximately 20 cases) by different names. A 48-years old female, presented with history of headache and dizziness associated with neck pain; restricted neck movements, drop attacks and occasional regurgitation of food since one year. Magnetic resonance imaging disclosed a right cerebellar mass lesion. Gross total resec- tion of the tumour was accomplished through a suboccipital craniotomy. The excised tissue was diagnosed as cerebellar liponeurocytoma, a rare entity, based on histopathological examination and immunohistochemistry. The morphological appearance of this neoplasm can be confused with that of oligodendroglioma, neurocytoma, ependymoma, medulloblastoma, solid hemangioblastoma and metastatic carcinomas etc., with unpredictable prognosis, which require postoperative radiotherapy, hence the importance of accurately diagnosing this rare neoplasm. This tumour should be added to the differential diagnosis of mass lesions of the posterior fossa. Key words: Liponeurocytoma, Cerebellum, Posterior cranial fossa Sreedhar Babu KV, Chowhan AK, Rukmangadha N, Prasad BCM, Kumaraswamy Reddy M. Cerebellar liponeurocytoma: a case- report. J Clin Sci Res 2012;1:39-42. INTRODUCTION liponeurocytoma with clinical, histological, and radiological studies. -

Leptomeningeal Dissemination of a Pediatric Neoplasm with 1P19q Deletion Showing Mixed Immunohistochemical Features of an Oligodendroglioma and Neurocytoma

Acta Neurochir DOI 10.1007/s00701-010-0674-x CASE REPORT Leptomeningeal dissemination of a pediatric neoplasm with 1p19q deletion showing mixed immunohistochemical features of an oligodendroglioma and neurocytoma Richard B. Rhiew & Sunil Manjila & Andrew Lozen & Murali Guthikonda & Sandeep Sood & William J. Kupsky Received: 24 February 2010 /Accepted: 21 April 2010 # Springer-Verlag 2010 Abstract Leptomeningeal dissemination of an oligoden- Keywords Leptomeningeal dissemination . droglioma is rarely reported in the neurosurgical literature, Oligodenroglioma . Neurocytoma . Mixed tumor especially in cases with a classical 1p19q deletion. The authors describe a case wherein a 1p19q deletion in a disseminated tumor with mixed immunohistochemical Introduction features of oligodendroglioma and neurocytoma was encountered and treated. Stereotactic right frontal craniot- Apart from the diagnostic dilemma of distinguishing omy was undertaken for obtaining definitive histological between neurocytomas and oligodendrogliomas, the recog- diagnosis. The results revealed a neuroectodermal neoplasm nition of rare mixed glial and neurocytic tumors presents an with histologic and immunohistochemical features of obstacle in tumor classification. Reports of leptomeningeal oligodendroglioma and neurocytoma. FISH analysis con- dissemination of tumors in this category are extremely rare, firmed classical 1p19q deletion. The patient was treated particularly those harboring the classic 1p19q co-deletion. postoperatively with chemotherapy and radiation therapy. The authors present such a histological variant of oligoden- He showed good clinical response and remains alive droglioma with evidence of extensive craniospinal lepto- 16 months after diagnosis. meningeal dissemination (LMD). The present case report highlights the importance of recognizing this discrete subtype of low-grade craniospinal neoplasms, which carry : : R. B. Rhiew S. Manjila M. Guthikonda features of both tumors and therefore are not classified Department of Neurosurgery, using the existing WHO system for CNS tumors. -

Ependimoma Sellar: Reporte De Caso Y Revisión De La Literatura

Ependimoma Sellar: Reporte de Caso y Revisión de la Literatura Fuenmayor-Duche Tatiana [email protected] Residente de Neurocirugía, Hospital de Especialidades Eugenio Espejo, Quito-Ecuador Ortiz-Ordonez Andrea [email protected] Residente de Neurocirugía, Hospital de Especialidades Eugenio Espejo, Quito-Ecuador Universidad San Francisco de Quito USFQ, Colegio de Ciencias de la Salud, calle Diego de Robles s/n y Pampite, Quito 170901, Ecuador Bucheli-Quezada Paul [email protected] Residente de Neurocirugía, Hospital de Especialidades Eugenio Espejo, Quito-Ecuador Universidad San Francisco de Quito USFQ, Colegio de Ciencias de la Salud, calle Diego de Robles s/n y Pampite, Quito 170901, Ecuador Quintanilla-González Chrystin [email protected] Residente de Neurocirugía, Hospital de Especialidades Eugenio Espejo, Quito-Ecuador Ayala-Ortiz Daniel Alejandro [email protected] Universidad Central del Ecuador RESUMEN El ependimoma es una neoplasia neuroectodérmica cuya localización principal es infratentorial en niños y espinal en adultos. Solo se han informado unos pocos casos de localización sellar atípica y no existe un protocolo de diagnóstico o manejo estandarizado para estos casos. Se informa un caso poco frecuente de ependimoma sellar en un adulto con deterioro cognitivo y visual. La sospecha clínica de esta entidad, así como la máxima resección quirúrgica segura, pueden permitir un diagnóstico certero y mejorar el abordaje terapéutico. Se necesitan más estudios sobre este tema para evaluar el tratamiento y la supervivencia a largo plazo. Palabras clave: Ependimoma intracraneal del adulto, Silla turca, Neurocirugía Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, Ciudad de México, México. ISSN 2707-2207 / ISSN 2707-2215 (en línea), mayo-junio, 2021, Volumen 5, Número 3. -

DNA Methylation-Based Reclassification of Olfactory Neuroblastoma

manuscript Click here to download manuscript Capper Engel Stichel et al. manuscript revision v9.docx Click here to view linked References DNA methylation-based reclassification of olfactory neuroblastoma David Capper1, 2, 13 *, Nils W. Engel3, 4 *, Damian Stichel1 *, Matt Lechner5, 6, 7, Stefanie Glöss13, Simone Schmid13, Christian Kölsche1, 2, Daniel Schrimpf1, 2, Judith Niesen23, 24, Annika K. Wefers1, 2, David T. W. Jones8, 9, Martin Sill8, 9, Oliver Weigert10, Keith L. Ligon11, Adriana Olar12, Arend Koch13, Martin Forster6, 7, Sebastian Moran26, Oscar M. Tirado27, Miguel Sáinz-Japeado27, Jaume Mora28, Manel Esteller26, 29, 30, Javier Alonso31, Xavier Garcia del Muro32, Werner Paulus14, Jörg Felsberg15, Guido Reifenberger15, Markus Glatzel16, Stephan Frank17, Camelia M. Monoranu18, Valerie J. Lund5, 7, Andreas von Deimling1, 2, Stefan Pfister8, 9, 25, Rolf Buslei19 +, Julika Ribbat-Idel20 ⱡ, Sven Perner20, ⱡ, Volker Gudziol21, Matthias Meinhardt22 and Ulrich Schüller3, 16, 23, 24 * These authors contributed equally to this work Correspondence should be addressed to U.S. ([email protected]), tel.: +49 (0) 40 7410 – 54968, fax: +49 (0) 40 7410 - 40350 1 Clinical Cooperation Unit Neuropathology, German Cancer Consortium (DKTK), German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany 2 Department of Neuropathology, University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany 3 Center for Neuropathology, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, Germany 4 Department of Oncology and Hematology with Sections Bone Marrow Transplant and Pneumology, Hubertus -

Summary Review I Have Focused on the Most Significant Complication of Bradycardia, I.E., CV Death

CV = cardiovascular; HF = heart failure; HR = heart rate; IHD = ischemic heart disease; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; MI = myocardial infarction The results of these three outcome trials are complex, inconsistent, and difficult to interpret. On the one hand SHIFT appears to demonstrate a highly significant benefit for HF hospitalizations in HF patients with higher heart rates and intolerant of, or inadequately dosed with, BBs. Mortality in SHIFT leans favorable. On the other hand BEAUTIFUL (Fox, Ford et al. 2008) failed to show any HF hospitalization or mortality benefit in IHD patients with reduced systolic function. While BEAUTIFUL suggested an MI benefit not seen in SHIFT, the large confirmatory trial SIGNIFY (Fox, Ford et al. 2014) failed to confirm this benefit and even suggests a detrimental impact in patients with symptomatic angina. Furthermore, SHIFT was performed entirely outside the U.S. with practice patterns, e.g., little intracardiac defibrillator (ICD) and cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) use, differing from U.S. guidelines and raising the issue of relevance to U.S. practice. Additionally, analyses of SHIFT suggest several significant drug interactions and subgroup variations. In this review I present the data addressing all of these issues. Finally, I propose and justify a modified indication for ivabradine use in HF patients. 2. Background/Regulatory History/Previous Actions/Foreign Regulatory Actions/Status All studies were not conducted under U.S. IND. Ivabradine was approved in Europe for the treatment of angina in 2005 and in 2012 for the treatment of heart failure (HF) in patients in sinus rhythm and whose heart rate is ≥ 75 bpm in combination with standard therapy including beta blockers (BBs) or when beta blockers are not tolerated. -

Clinical Content Data Points Dictionary

Abstracted Primary Childhood Cancer Diagnoses within Abstracted Diagnosis Groups Data Freeze: June 30, 2017 Broad Diagnosis Group (diaggrp) Diagnosis (diag) Acute lymphoblastic leukemia Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, B Lineage, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, B-Cell, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, B-Cell, Mature, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, B-Lineage, Transitional, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Common , Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Common Pre B, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Common, Early Pre B, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Early B, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Early Pre B, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Early Pre B, Hematological Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Early Pre-B, Atypical, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Early T Cell Precursor, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Mixed Early Pre B And Pre B, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Mixed Pre B And Mature B, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Non B, Non Pre B, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Pre B And Pre B Transitional, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Pre-B, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Pre-T Cell, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Progenitor B Cell, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, T-Cell, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Transitional Pre B, Bone Marrow Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Undifferentiated, Bone Marrow T Cell Large Granular Lymphocytic -

Case Report Collision Tumour Affecting the Paranasal Sinuses of a Geriatric Donkey S

EQUINE VETERINARY EDUCATION / AE / APRIL 2012 163 Case Report Collision tumour affecting the paranasal sinuses of a geriatric donkey S. Witte*, P. O. E. Mueller†, C. Kosarek‡, J. L. Webb§ and E. W. Howerth§ Qatar Equestrian Federation, Doha, State of Qatar; Departments of Large Animal Medicine† and Pathology§, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia; and ‡Animal Cancer Care Clinic, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA. Keywords: horse; donkey; sinonasal adenocarcinoma; spindle cell carcinoma; frontal sinus; maxillary sinus Summary The incidence of equine sinonasal tumours is difficult to quantify but they remain relatively uncommon (Head and Tumours of the paranasal sinuses are relatively uncommon Dixon 1999; Tremaine and Dixon 2001a). This makes the in the horse. A collision tumour occurs when 2 separate phenomenon of 2 separate neoplasms growing tumour types arise in close proximity to each other and concurrently even more unusual. Two separate neoplasms encroach on one another. This report describes the arising in close proximity to each other and invading each presence of neoplasia comprising glandular tissue and other are collectively known as a collision tumour. Collision spindle cells growing concurrently in the frontal and tumours have rarely been reported in the veterinary caudal maxillary sinus of a geriatric donkey. As far as the literature (Barnes et al. 1990; Inoue and Wada 2000). They authors are aware, this is the first description of a possible are uncommon in man and few case reports describe their collision tumour in an equid. location in the sinuses or nasal cavity (Cantor et al. 1981; Kumar et al. 2004; Satake et al.