Building on Opportunities. Cooperating with Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IFC and Germany Partners in Private Sector Development

IFC and Germany Partners in Private Sector Development OVERVIEW IFC, a member of the World Bank Group, is the largest global development institution focused on the private sector in emerging markets. Working with over 2,000 businesses worldwide, IFC’s long-term investments in developing countries exceeded $19 billion in fiscal year (FY) 2019. IFC is an active partner of German companies interested in investing in emerging markets. Of IFC’s long-term committed portfolio of $1.7 billion with German partners, 49% is in manufacturing, agribusiness and services, 28% in infrastructure, 21% in financial markets and the remaining 2% in telecom, media, and technology. Investments are spread across regions, namely 46 % in Europe and Central Asia, 18% in East Asia and the Pacific, and 14% in Latin America and the Caribbean and Sub-Saharan Africa respectively. PARTNERSHIP WITH THE GOVERNMENT AND DEVELOPMENT FINANCE INSTITUTION Germany’s development institutions, KfW Bankengruppe (KfW), which includes DEG, are important partners and act as long-term co-lenders in a variety of industry sectors, including agri-finance, microfinance and sustainable energy. As of June 2019, Germany provided cumulative funding of over $57 million to support IFC Advisory Services, including over $16 million in FY19 for the PPP Advisory Fund for Infrastructure Investments in Developing Countries (over $7 million), and for the Energy Efficiency Support Program for Ukraine ($11 million). In December 2017, KfW contributed $12 million for IFC’s Support Program for the G20 Compact with Africa Initiative, which aims to unlock sustainable, inclusive private sector investment opportunities in Africa. IFC’s Long-Term Investment Portfolio with German Sponsors As of FY19 (ending in June 2019), IFC’s long-term investment portfolio with German sponsors amounted to $1.7 billion. -

Download File

Yemen Country Office Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Yemen/2019/Mahmoud Fadhel Reporting Period: 1 - 31 October 2019 Highlights Situation in Numbers • In October, 3 children were killed, 16 children were injured and 3 12.3 million children in need of boys were recruited by various parties to the conflict. humanitarian assistance • 59,297 suspected Acute Watery Diarrhoea (AWD)/cholera cases were identified and 50 associated deaths were recorded (0.08 case 24.1 million fatality rate) in October. UNICEF treated over 14,000 AWD/cholera people in need suspected cases (one quarter of the national caseload). (OCHA, 2019 Yemen Humanitarian Needs Overview) • Due to fuel crisis, in Ibb, Dhamar and Al Mahwit, home to around 400,000 people, central water systems were forced to shut down 1.71 million completely. children internally displaced • 3.1 million children under five were screened for malnutrition, and (IDPs) 243,728 children with Severe Acute Malnutrition (76 per cent of annual target) admitted for treatment. UNICEF Appeal 2019 UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status US$ 536 million Funding Available* SAM Admission 76% US$ 362 million Funding status 68% Nutrition Measles Rubella Vaccination 91% Health Funding status 77% People with drinking water 100% WASH Funding status 64% People with Mine Risk Education 82% Child Funding status 40% Protection Children with Access to Education 29% Funding status 76% Education People with Social Economic 61% Assistance Policy Social Funding status 38% People reached with C4D efforts 100% *Funds available includes funding received for the current C4D Funding status 98% appeal (emergency and other resources), the carry- forward from the previous year and additional funding Displaced People with RRM Kits 59% which is not emergency specific but will partly contribute towards 2019 HPM results. -

A German Perspective

15 A German Perspective HANS W. REICH This chapter will address some issues regarding Kreditanstalt für Wieder- aufbau’s (KfW’s) so-called market window. But before doing so, it will be useful to comment on how the German official trade finance system competes with the system in other nations. The Question of Competition Competition clearly exists between export credit agencies (ECAs) and the market windows of other official export financing agencies, such as KfW. Because these institutions were all established to support domestic companies in their exporting activities, and because this remains their main business today, it is obvious that there must be some kind of com- petition among them. But the existence of competition among official ECAs with different charters is no proof of unfair practice. The question of competition in trade finance should be examined in a broader perspective. Trade policy has always been an important instru- ment in national economic policy, either with an aim to protect the domes- tic economy against foreign competitors or to assist domestic companies in gaining access to foreign markets. Despite the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the World Trade Organization, loopholes remain for public action to shape trade and investment flows. There are many Hans W. Reich is chairman of the board of managing directors of Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau, Frankfurt. 221 Institute for International Economics | http://www.iie.com ways to influence trade patterns other than export finance. Political inter- ventions, foreign policy, and geostrategic military interests definitely play a role, and perhaps a much greater role than export finance. -

Form 18-K/A Amendment No. 4 Annual Report

Form 18 -K/A Page 1 of 45 18 -K/A 1 d905133d18ka.htm FORM 18 -K/A Table of Contents SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 18-K/A For Foreign Governments and Political Subdivisions Thereof AMENDMENT NO. 4 to ANNUAL REPORT of KfW (Name of Registrant) Date of end of last fiscal year: December 31, 2013 SECURITIES REGISTERED (As of the close of the fiscal year)* AMOUNT AS TO WHICH REGISTRATION IS NAMES OF EXCHANGES ON TITLE OF ISSUE EFFECTIVE WHICH REGISTERED N/A N/A N/A * The registrant files annual reports on Form 18 -K on a voluntary basis. Name and address of person authorized to receive notices and communications from the Securities and Exchange Commission: KRYSTIAN CZERNIECKI Sullivan & Cromwell LLP Neue Mainzer Strasse 52 60311 Frankfurt am Main, Germany http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/821533/000119312515132502/d905133d18k ... 23/ 04/ 2015 Form 18 -K/A Page 2 of 45 Table of Contents The undersigned registrant hereby amends its Annual Report on Form 18-K for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2013, as subsequently amended, as follows: - Exhibit (d) is hereby amended by adding the text under the caption “Presentation of Financial and Other Information ” on page 1 hereof to the “Presentation of Financial and Other Information ” section; - Exhibit (d) is hereby amended by adding the text under the caption “Exchange Rate Information” on page 1 hereof to the “Exchange Rate Information ” section; - Exhibit (d) is hereby amended by replacing the text in the “Recent Developments —The Federal Republic of Germany—Overview -

Livelihoods Assistance – Active Partners Reporting for January 2021

Partners Monthly Presence (4W Map): Livelihoods Assistance – Active Partners 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 N Amran Reporting for January 2021 <Sadjhg 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 E 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 r r r r r r r r Saáda 4 partners M e e e e e e e 4 partners Amanat Al asimah 2 partners e Amran A E b b b b b b b b Partners by type & volume of response SFD, UNDP/SFD, WFP/Oxfam 7 partners Y Sana'a m m m m m m m SFD, UNDP/SFD, UNDP/SFD m e e e e e e e WFP/Oxfam e UNDP/SFD, WFP/IRY, WFP/RI Partner Type Volume of Response c c c c c c c c e e e e e e e e 30% INGOs D D D D D D D D FAO/Ghadaq - - - - - - - - NNGOs 4% s s s s s s s s e e e e e e e Hajjah 8 partners e i i i i i i i i t t t t t t t t Amran UN Agencies and partners i i i i i i i i 66% v v v v v v v CARE, HAY, SFD, UNDP/SFD, v i i i i i i i i t t t t t t t WFP/RI t c c c c c c c c Sa'ada a a a a a a a CARE, FAO/RADF a r r r r r r r r e e e e e e e Ale Jawf st st st st st st st st u u u u u u u u l l l l l l l Al Mahwit 5 partners Al Jawf l 2 partners Al Maharah C C C C C C C C CARE, UNDP/SFD, WFP/Care, e e e e e e e SFD, UNDP/SFDe Hadramaut WFP/SDF r r r r r r r r u u u u u u u Hajjah u Amran 9 partners t t t t t t t Amran t Hadramaut l l l l l l l CARE l u u u u u u u u UNDP/SFD, WFP/BCHR, c c c c c c c c i i i i i i i 6 partners i WFP/FMF r r r r r r r Dhamar r Amanat g g g g g g g SFD, UNDP/SFD, g YLDF A A A A A A A A ! WFP/IRY, WFP/SDF Al Asimah . -

Paleostress Analysis of the Volcanic Margins of Yemen Khaled Khanbari, Philippe Huchon

Paleostress analysis of the volcanic margins of Yemen Khaled Khanbari, Philippe Huchon To cite this version: Khaled Khanbari, Philippe Huchon. Paleostress analysis of the volcanic margins of Yemen. Arabian Journal of Geosciences, Springer, 2010, 3, pp.529-538. 10.1007/s12517-010-0164-8. hal-00574208 HAL Id: hal-00574208 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00574208 Submitted on 7 Apr 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arab. J. Geosciences, Accepted 26-05-2010 Paleostress analysis of the volcanic margins of Yemen Khaled Khanbaria,b, Philippe Huchonc,d a Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Sana’a University, PO Box 12167, Sana’a, Yemen Email: [email protected] b Yemen Remote Sensing and GIS Center, Yemen c iSTeP, UMR 7193, UPMC Université Paris 6 Case 129, 4 place Jussieu 75005 Paris, France d iSTeP, UMR 7193, CNRS, Paris, France ________________________________________________________________________ Abstract The western part of Yemen is largely covered by Tertiary volcanics and is bounded by volcanic margins to the west (Red Sea) and the south (Gulf of Aden). The oligo-miocene evolution of Yemen results from the interaction between the emplacement of the Afar plume, the opening of the Red Sea and the westward propagation of the Gulf of Aden. -

Kfw Entrepreneurship Monitor 2021

KfW Research KfW Entrepreneurship Monitor 2021 Start-up activity 2020 with light and shade: Coronavirus crisis brings new low in full-time business starters but also holds opportunities Imprint Published by KfW Research KfW Group Palmengartenstrasse 5-9 60325 Frankfurt / Main Phone +49 69 7431-0, Fax +49 69 7431-2944 www.kfw.de Author Dr Georg Metzger, KfW Group Phone +49 69 7431-9717 Copyright cover image Source: Getty Images / Photographer: Datacraft Co Ltd Frankfurt / Main, June 2021 Start-up activity 2020 with light and shade: Coronavirus crisis brings new low in full-time business starters but also holds opportunities Coronavirus crisis ruined positive outlook for 2020 Number of business start-ups fell Start-up activity in Germany decreased in 2020. Com- Start-up activity in Germany dropped in 2020 as a pared with 2019, 68,000 fewer persons ventured into result of the outbreak of the coronavirus crisis. The self-employment, launching 537,000 businesses – a number of business starters decreased to 537,000. drop of over 11%. The start-up rate fell to 104 business Full-timers and part-timers were equally affected. starters per 10,000 persons aged 18 to 64 years, after The number of part-time business start-ups dropped 117 in 2019 (Figure 1). Full-time and part-time start-up to 336,000, while the number of full-time start-ups activity developed similarly in 2020 but the decline in slipped to 201,000, a new low. full-time start-up activity was marginally stronger. The number of full-time business starters fell to 201,000 The crisis: an opportunity for many (-27,000 -12%) – a new low since the beginning of the The year of the coronavirus crisis saw a larger share time series. -

Deutsche Lufthansa Aktiengesellschaft in Respect of Non-Equity Securities Within the Meaning of Art

Base Prospectus 17 November 2020 This document constitutes the base prospectus of Deutsche Lufthansa Aktiengesellschaft in respect of non-equity securities within the meaning of Art. 2 (c) of Regulation (EU) 2017/1129 of the European Parliament and of the Council of June 14, 2017 (the “Prospectus Regulation”) for the purposes of Article 8(1) of the Prospectus Regulation (the “Base Prospectus”). Deutsche Lufthansa Aktiengesellschaft (Cologne, Federal Republic of Germany) as Issuer EUR 4,000,000,000 Debt Issuance Programme (the “Programme”) In relation to notes issued under this Programme, application has been made to the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (the “CSSF”) of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (“Luxembourg”) in its capacity as competent authority under the Luxembourg act relating to prospectuses for securities dated 16 July 2019 (Loi du 16 juillet 2019 relative aux prospectus pour valeurs mobilières et portant mise en oeuvre du règlement (UE) 2017/1129, the “Luxembourg Law”) for approval of this Base Prospectus. The CSSF only approves this Base Prospectus as meeting the standards of completeness, comprehensibility and consistency imposed by the Prospectus Regulation. Such approval should not be considered as an endorsement of the economic or financial opportunity of the operation or the quality and solvency of the Issuer or of the quality of the Notes that are the subject of this Base Prospectus. Investors should make their own assessment as to the suitability of investing in the Notes. By approving this Base Prospectus, the CSSF does not assume any responsibility as to the economic and financial soundness of any issue of Notes under the Programme and the quality or solvency of the Issuer. -

Financial Stabilization Package Briefing Materials

Financial Stabilization Package Briefing Materials Frankfurt June 2020 Disclaimer The information herein is based on publicly available information. It This presentation contains statements that express the Company‘s has been prepared by the Company solely for use in this opinions, expectations, beliefs, plans, objectives, assumptions or presentation and has not been verified by independent third parties. projections regarding future events or future results, in contrast with No representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, is statements that reflect historical facts. While the Company always made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the fairness, intends to express its best knowledge when it makes statements accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information or the about what it believes will occur in the future, and although it bases opinions contained herein. The information contained in this these statements on assumptions that it believes to be reasonable presentation should be considered in the context of the when made, these forward-looking statements are not a guarantee circumstances prevailing at that time and will not be updated to of performance, and no undue reliance should be placed on such reflect material developments which may occur after the date of the statements. Forward-looking statements are subject to many risks, presentation. uncertainties and other variable circumstances that may cause the statements to be inaccurate. Many of these risks are outside of the Company‘s control and could cause its actual results (positively or The information does not constitute any offer or invitation to sell, negatively) to differ materially from those it thought would occur. -

European Airlines: Brace for More Turbulence

7 September 2020 Corporates European airlines: brace for more turbulence What’s next after demand shock, bailouts? European airlines: brace for more turbulence What’s next after demand shock, bailouts? Government support has helped large European network carriers avert a liquidity crisis, with air traffic to fall at least 50% in 2020. Deleveraging after the Covid-19 Analysts crisis will be a challenge for a sector not known for rich free cash flow generation. Werner Stäblein European airlines secured direct financial government support of more than EUR 25bn +49 69 667738912 after the onset of the coronavirus crisis earlier this year. The liquidity buffers most airlines [email protected] had in place were insufficient to cope with a crisis of the magnitude brought on by the pandemic which led to the grounding of almost all aircraft in April and May. Sebastian Zank, CFA +49 30 27891 225 The funding situation is now stabilised due to state aid. However, future deleveraging and [email protected] operational restructuring - including the downsizing of operations - will prove challenging Azza Chammem for some industry players. Visibility on traffic recovery is low. Customers for long-haul and +49 30 27891 240 short-haul traffic continue to book on very short notice. Business travel is recovering only [email protected] slowly. Air freight is one sector that has done comparably well, but with gradually rising passenger traffic comes increased freight capacity on passenger aircraft. Such an Media increase will compress elevated cargo yields. The air freight business is also too small to offset shortfalls in revenue from passenger travel. -

Emergency Plan of Action (Epoa) Yemen: Floods 2021

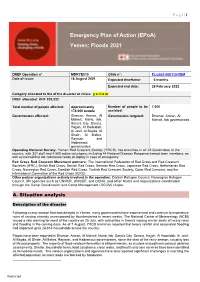

P a g e | 1 Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Yemen: Floods 2021 DREF Operation n° MDRYE010 Glide n°: FL-2021-000110-YEM Date of issue: 16 August 2021 Expected timeframe: 6 months Expected end date: 28 February 2022 Category allocated to the of the disaster or crisis: y e l l o w DREF allocated: CHF 205,332 Total number of people affected: Approximately Number of people to be 7,000 174,000 people assisted: Governorates affected: Dhamar, Amran, Al Governorates targeted: Dhamar, Amran, Al Mahwit, Marib, Ibb, Mahwit, Ibb governorates Sana’a City, Sana’a, Hajjah, Al Hodeidah, Al Jawf, Al Bayda, Al Dhale, Al Mahra, Raymah and Hadramout governorates Operating National Society: Yemen Red Crescent Society (YRCS) has branches in all 22 Governates of the country, with 321 staff and 4,500 active volunteers, including 44 National Disaster Response trained team members, as well as trained first aid volunteers ready to deploy in case of emergency. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners: The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), British Red Cross, Danish Red Cross, German Red Cross, Japanese Red Cross, Netherlands Red Cross, Norwegian Red Cross, Swedish Red Cross, Turkish Red Crescent Society, Qatar Red Crescent, and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Danish Refugee Council, Norwegian Refugee Council, UN agencies such as UNHCR, UNICEF, and OCHA, and other NGOs and organizations coordinated through the Camp Coordination and Camp Management (CCCM) cluster. A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster Following a rainy season that was delayed in Yemen, many governorates have experienced and continue to experience rains of varying intensity accompanied by thunderstorms in recent weeks. -

General and Bilateral Brief Hesse

1 Consulate General of India Frankfurt *** General and Bilateral Brief: 0 Hessen-India Hesse (German: Hessen) is home to one of the largest European airports (Frankfurt Airport) and also offers an excellent transport network. The state capital is Wiesbaden and the largest city is Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt, as an international financial centre, has a strong influence on Hesse as a service region. Similarly, well-known international industrial companies define Hesse as a technology location at the heart of European markets. The important industries are automotive and supply industries, Biotechnology, Cultural and creative industries, Financial services, Aerospace, Mechanical and plant engineering, Medical technology, Tourism. Hesse also boasts beautiful nature reserves, historical castles and palaces, as well as the Rheingau vineyards which are renowned for its excellent wines all over the world. Salient Features of Hesse 1. Geography: Hesse is situated in west-central Germany, with state borders the German states of Lower Saxony, Thuringia, Bavaria, Baden-Württemberg, Rhineland-Palatinate, and North Rhine- Westphalia. It is the greenest state in Germany, as forest covers 42% of the state. Most of the population of Hessen is in the southern part in the Rhine Main Area. The principal cities of the area include Frankfurt am Main, Wiesbaden, Darmstadt, Offenbach, Hanau, Gießen, Wetzlar, and Limburg. Other major towns in Hesse are Fulda , Kassel and Marburg. The densely populated Rhine-Main region is much better developed than the rural areas in the middle and northern parts of Hesse. The most important rivers in Hesse are the Fulda and Eder rivers in the north, the Lahn in the central part of Hesse, and the Main and Rhine in the south.