Thomas J. Watson Library Digital Collections | the Metropolitan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(QTR) Apparel Program Supercharges Licensing in Complementary Categories Across Isaac Mizrahi, H Halston, and Judith Ripka Brands

November 9, 2016 Xcel Brands, Inc. Quick Time Response (QTR) Apparel Program Supercharges Licensing in Complementary Categories Across Isaac Mizrahi, H Halston, and Judith Ripka Brands NEW YORK, Nov. 09, 2016 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Xcel Brands, Inc. (NASDAQ:XELB) is pleased to announce multiple new licenses across its owned brands as licensees look to pursue growth in categories complementary to Xcel's successful quick time response (QTR) apparel programs at Lord & Taylor and Hudson's Bay stores. CEO and Chairman of Xcel Brands, Inc. Robert W. D'Loren remarked, "With the rise of a ‘see-now-buy-now' consumer shopping mentality and the need to respond to trends as they happen, Xcel created an innovative solution to bring exclusive brands to our department store partners in a quick time response format. The rapid growth of these apparel programs has generated excitement within the licensing community across numerous complementary categories. With these new partnerships we will continue to build meaningful lifestyle brands under the IMNYC Isaac Mizrahi and H Halston labels." New licensees under the Isaac Mizrahi brand include tech accessories and luggage, with product set to retail in Spring 2017. Xcel Brands, Inc. entered into a licensing agreement with Bytech NY Inc. for tech accessories for smartphones, PCs, tablets, and personal audio across the Isaac Mizrahi New York, IMNYC Isaac Mizrahi, and Isaac Mizrahi Live! labels. Xcel also entered into a licensing agreement with Longlat Inc. for a collection of hard and soft luggage under the Isaac Mizrahi New York and Isaac Mizrahi Live! labels. New licensees under the H Halston brand include sleepwear and intimates, legwear and slippers, and non-optical sunglasses and readers. -

The Temperamentals

Temperamentals.qxd 5/18/2012 1:59 PM Page i THE TEMPERAMENTALS BY JON MARANS ★ ★ DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. Temperamentals.qxd 5/18/2012 1:59 PM Page 2 THE TEMPERAMENTALS Copyright © 2010, Jon Marans All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of THE TEMPERAMENTALS is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recita- tion, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and dis- tribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, informa- tion storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into for- eign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for THE TEMPERAMENTALS are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. -

Calm Down NEW YORK — East Met West at Tiffany on Sunday Morning in a Smart, Chic Collection by Behnaz Sarafpour

WINSTON MINES GROWTH/10 GUCCI’S GIANNINI TALKS TEAM/22 WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’MONDAY Daily Newspaper • September 13, 2004 • $2.00 Accessories/Innerwear/Legwear Calm Down NEW YORK — East met West at Tiffany on Sunday morning in a smart, chic collection by Behnaz Sarafpour. And in the midst of the cross-cultural current inspired by the designer’s recent trip to Japan, she gave ample play to the new calm percolating through fashion, one likely to gain momentum as the season progresses. Here, Sarafpour’s sleek dress secured with an obi sash. For more on the season, see pages 12 to 18. Hip-Hop’s Rising Heat: As Firms Chase Deals, Is Rocawear in Play? By Lauren DeCarlo NEW YORK — The bling-bling world of hip- hop is clearly more than a flash in the pan, with more conglomerates than ever eager to get a piece of it. The latest brand J.Lo Plans Show for Sweetface, Sells $15,000 Of Fragrance at Macy’s Appearance. Page 2. said to be entertaining suitors is none other than one that helped pioneer the sector: Rocawear. Sources said Rocawear may be ready to consider offers for a sale of the company, which is said to generate more than $125 million in wholesale volume. See Rocawear, Page4 PHOTO BY GEORGE CHINSEE PHOTO BY 2 WWD, MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 2004 WWW.WWD.COM WWDMONDAY J.Lo Talks Scents, Shows at Macy’s Accessories/Innerwear/Legwear By Julie Naughton and Pete Born FASHION The spring collections kicked into high gear over the weekend with shows Jennifer Lopez in Jennifer Lopez in from Behnaz Sarafpour, DKNY, Baby Phat and Zac Posen. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Jewish-And-Asian-Pacific-Heritage

In May 2021, We celebrated Jewish American and Asian American Heritage! Click the buttons to the right to explore more about Jewish American and Asian Pacific American history. Today, America is home to around 7 million Jewish Americans. Click the buttons below for more! Click the button below to return to the main menu Learn Jewish Americans may identify as Jewish based on religion, ethnic upbringing, or both. The Jewish population in America is diverse and includes all races and ethnicities. Did you know? • Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax, one of the most famous Jewish athletes in American sports, made national headlines when he refused to pitch in the first game of the 1965 World Series because it fell on Yom Kippur. • Hanukkah is not the most popular holiday in Jewish heritage. Passover is the most celebrated of all Jewish holidays with more than 70% of Jewish Americans taking part in a seder, its ritual meal. Hanukkah may be the best known Jewish holiday in the United States. But despite its popularity in the U.S., Hanukkah is ranked one of Judaism’s minor festivals, and nowhere else does it garner such attention. The holiday is mostly a domestic celebration, although special holiday prayers also expand synagogue worship. Explore Hanukkah The Menorah Hanukkah may be the most well The Hanukkah menorah (or chanukiah) is known Jewish holiday in the United a nine-branched candelabrum lit during the States. But despite its popularity in eight-day holiday of Hanukkah, as opposed the U.S., Hanukkah is ranked one to the seven-branched menorah used in of Judaism’s minor festivals, and the ancient Temple or as a symbol. -

Looking Back at Mccardell: It's a Lot Like Looking at Todayi4

58 L-f THE NEW YQRK TIMES, WEDNESDAY, MA\ Y 24,1972 — yamily /ood fashions' /iirntshirigs: Looking Back at McCardell: It's a Lot Like Looking at Todayi4 . By BERVADilME MORRIS The Paris fashion world has Chanel as its monument. New 1 ^Yorlc has_CJaire McCardehV "Both- women, though de ceased, have influenced the current casual mood of fash ion. Chanel invented the sweater, McCardell invented the American Look. » It was born in the Depres-' sion-ridden nineteen-thirties-, flourished during the war •yeara of the forties, felLoff at the end of the fifties (McCardell died in 1958), and all but disappeared, in the sixties, when_Paris regained^ center-stage" with swinging , London close behind. "Now that sportswear, the crux of the American Look, . has: become the dominant- • trend-on Seventh Avenue and other satellite fashion cen ters, the Fashion Institute of. Technology felt the time was -rightfor. a McCardell retro- • apettlve. • • • • • ' —• Tt.wasjhcld Monday night In the school's auditorium, 227. West 27th Street, fol lowed by a $125-a-person black tie supper dance in the lobby. Like a Premiere Seventh Avenue, which supports the state-run col lege, came out in droves. Stu dents lined up outside trie *"scTibo1"to cheer arrival fit tlie limousines carrying such per sonalities as Lynn Revson (whose- husband,' ChBrles, heads Revlon) in her sequin- sparkling red jacket over a black dress by Norman No- rel);—Beth Levine, the shoe designer, in her Halston caf tan, and Jerry Silverman, the., manufacturer, with Pauline Trigdre, in herTrigore. It had all the earmarks of a Hollywood premiere, way hack when. -

2010–2011 Our Mission

ANNUAL REPORT 2010–2011 OUR MISSION The Indianapolis Museum of Art serves the creative interests of its communities by fostering exploration of art, design, and the natural environment. The IMA promotes these interests through the collection, presentation, interpretation, and conservation of its artistic, historic, and environmental assets. FROM THE CHAIRMAN 02 FROM THE MELVIN & BREN SIMON DIRECTOR AND CEO 04 THE YEAR IN REVIEW 08 EXHIBITIONS 18 AUDIENCE ENGAGEMENT 22 PUBLIC PROGRAMS 24 ART ACQUISITIONS 30 LOANS FROM THE COLLECTION 44 DONORS 46 IMA BOARD OF GOVERNORS 56 AFFILIATE GROUP LEADERSHIP 58 IMA STAFF 59 FINANCIAL REPORT 66 Note: This report is for fiscal year July 2010 through June 2011. COVER Thornton Dial, American, b. 1928, Don’t Matter How Raggly the Flag, It Still Got to Tie Us Together (detail), 2003, mattress coils, chicken wire, clothing, can lids, found metal, plastic twine, wire, Splash Zone compound, enamel, spray paint, on canvas on wood, 71 x 114 x 8 in. James E. Roberts Fund, Deaccession Sculpture Fund, Xenia and Irwin Miller Fund, Alice and Kirk McKinney Fund, Anonymous IV Art Fund, Henry F. and Katherine DeBoest Memorial Fund, Martha Delzell Memorial Fund, Mary V. Black Art Endowment Fund, Elizabeth S. Lawton Fine Art Fund, Emma Harter Sweetser Fund, General Endowed Art Fund, Delavan Smith Fund, General Memorial Art Fund, Deaccessioned Contemporary Art Fund, General Art Fund, Frank Curtis Springer & Irving Moxley Springer Purchase Fund, and the Mrs. Pierre F. Goodrich Endowed Art Fund 2008.182 BACK COVER Miller House and Garden LEFT The Wood Pavilion at the IMA 4 | FROM THE CHAIRMAN FROM THE CHAIRMAN | 5 RESEARCH LEADERSHIP From the In addition to opening the new state-of-the-art Conservation Science Laboratory this past March, the IMA has fulfilled the challenge grant from the Andrew W. -

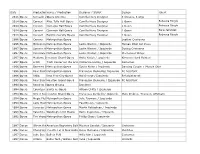

Date Production Name Venue / Production Designer / Stylist Design

Date ProductionVenue Name / Production Designer / Stylist Design Talent 2015 Opera Komachi atOpera Sekidrera America Camilla Huey Designer 3 dresses, 3 wigs 2014 Opera Concert Alice Tully Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 2014 Opera Concert Carnegie Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 2014 Opera Concert Carnegie Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Sara Jakubiak 2013 Opera Concert Bard University Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 1996 Opera Carmen Metropolitan Opera Leather Costumes 1996 Opera Midsummer'sMetropolitan Night's Dream Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Human Pillar Set Piece 1997 Opera Samson & MetropolitanDelilah Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Dyeing Costumes 1997 Opera Cerentola Metropolitan Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Mechanical Wings 1997 Opera Madame ButterflyHouston Grand Opera Anita Yavich / Izquierdo Kimonos Hand Painted 1997 Opera Lillith Tisch Center for the Arts OperaCatherine Heraty / Izquierdo Costumes 1996 Opera Bartered BrideMetropolitan Opera Sylvia Nolan / Izquierdo Dancing Couple + Muscle Shirt 1996 Opera Four SaintsMetropolitan In Three Acts Opera Francesco Clemente/ Izquierdo FC Asssitant 1996 Opera Atilla New York City Opera Hal George / Izquierdo Refurbishment 1995 Opera Four SaintsHouston In Three Grand Acts Opera Francesco Clemente / Izquierdo FC Assistant 1994 Opera Requiem VariationsOpera Omaha Izquierdo 1994 Opera Countess MaritzaSanta Fe Opera Allison Chitty / Izquierdo 1994 Opera Street SceneHouston Grand Opera Francesca Zambello/ Izquierdo -

Catwalk Copycats: Why Congress Should Adopt a Modified Version of the Design Piracy Prohibition Act, 14 J

Journal of Intellectual Property Law Volume 14 | Issue 2 Article 4 April 2007 Catwalk Copycats: Why Congress Should Adopt a Modified eV rsion of the Design Piracy Prohibition Act Laura C. Marshall University of Georgia School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Laura C. Marshall, Catwalk Copycats: Why Congress Should Adopt a Modified Version of the Design Piracy Prohibition Act, 14 J. Intell. Prop. L. 305 (2007). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl/vol14/iss2/4 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. Please share how you have benefited from this access For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marshall: Catwalk Copycats: Why Congress Should Adopt a Modified Version of CATWALK COPYCATS: WHY CONGRESS SHOULD ADOPT A MODIFIED VERSION OF THE DESIGN PIRACY PROHIBITION ACT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................... 307 II. BACKGROUND ............................................ 308 A. THE DESIGN PIRACY PROHIBITION ACT AND THE U.S. FASHION INDUSTRY ..................................... 309 1. ProposedFederal Legislation to Extend Intellectual Propen) Protection to Fashion Works ........................ 309 2. The Fashion Industty and the Prevalence of Knockoffs ............................................ 310 B. HISTORY OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY PROTECTION FOR FASHION WORKS AND CURRENT STATE OF THE LAW ........... 311 1. Design Patent ......................................... 311 2. Trademark and Trade Dress .............................. 313 3. Copyright ............................................ 314 C. INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY PROTECTION FOR FASHION DESIGNS IN EUROPE .................................... -

Kleidung / Mode / Couture / Kostümdesign Im Film: Eine Erste Bibliographie 2011

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Hans Jürgen Wulff; Ludger Kaczmarek Kleidung / Mode / Couture / Kostümdesign im Film: Eine erste Bibliographie 2011 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12753 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Wulff, Hans Jürgen; Kaczmarek, Ludger: Kleidung / Mode / Couture / Kostümdesign im Film: Eine erste Bibliographie. Hamburg: Universität Hamburg, Institut für Germanistik 2011 (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 122). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12753. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0122_11.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Medienwissenschaft / Hamburg: Berichte und Papiere 122, 2011: Mode im Film. Redaktion und Copyright dieser Ausgabe: Ludger Kaczmarek, Hans J. Wulff. ISSN 1613-7477. URL: http://www.rrz.uni-hamburg.de/Medien/berichte/arbeiten/0122_11.html Letzte Änderung: 20.2.2011. Kleidung / Mode / Couture / Kostümdesign im Film: Eine erste Bibliographie. Zusammengest. v. Hans J. Wulff u. Ludger Kaczmarek Inhalt: da, wo die Hobos sind, er riecht wie einer: Also ist er Einleitung einer. Warum sollte man jemanden für einen anderen Bibliographien halten als den, der er zu sein scheint? In Nichols’ Direktoria Working Girl (1988) nimmt eine Sekretärin heimlich Texte für eine Zeit die Rolle ihrer Chefin an, und sie be- nutzt auch deren Garderobe und deren Parfüm. -

Meet Pioneer of Gay Rights, Harry Hay

Meet Pioneer of Gay Rights, Harry Hay His should be a household name. by Anne-Marie Cusac August 9, 2016 Harry Hay is the founder of gay liberation. This lovely interview with Hay by Anne-Marie Cusac was published in the September 1998 issue of The Progressive magazine. Then-editor Matt Rothschild called Hay "a hero of ours," writing that he should be a household name. He wrote: "This courageous and visionary man launched the modern gay-rights movement even in the teeth of McCarthyism." In 1950 Hay started the first modern gay-rights organization, the underground Mattachine Society, which took its name from a dance performed by masked, unmarried peasant men in Renaissance France, often to protest oppressive landlords. According to Hay's 1996 book, Radically Gay, the performances of these fraternities satirized religious and political power. Harry Hay was one of the first to insist that lesbians and gay men deserve equality. And he placed their fight in the context of a wider political movement. "In order to earn for ourselves any place in the sun, we must with perseverance and self-discipline work collectively . for the first-class citizenship of Minorities everywhere, including ourselves," he wrote in 1950. At first, Hay could not find anyone who would join him in forming a political organization for homosexuals. He spent two years searching among the gay men he knew in Los Angeles. Although some expressed interest in a group, all were too fearful to join a gay organization that had only one member. But drawing on his years as a labor organizer, Hay persisted. -

A Glimpse at the History of the U.S. LGBTQ Community Part 1 by Valerie

A glimpse at the history of the U.S. LGBTQ community Part 1 by Valerie Etienne-Leveille LGBTQ is an acronym for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer or questioning (1). The acronym meaning is simple, yet it provides a glimpse to the varied and complex representative groups united in strength and solidarity toward a common cause which is equal rights for all individuals (2). The early LGBTQ Rights Movement Henry Gerber, a German immigrant, founded the first documented gay rights organization in the United States in 1924 (3)(4). The organization founded in Chicago was named The Society for Human Rights. Gerber’s organization published the earliest documented gay-interest newsletter called “Friendship and Freedom” (3)(5). Due to fear of continued harassment and persecution experienced by many individuals, subscription rates to the Friendship and Freedom newsletter were low. Henry Gerber and the members of his organization were not immune to the social and political hostilities occurring during this time. In 1925, Gerber’s organization disbanded because of unwarranted police raids, arrests, and negative media coverage. Nevertheless, Henry Gerber continued to advocate for gay rights through his writings and networking with the community (5). The Henry Gerber House A National Historic Landmark in Chicago, IL. Photo by Thshriver (5). Activists: Harry Hay (1912-2002) and William Dale Jennings (1917-2000) Harry Hay was an actor, Communist labor organizer, musicologist, theoretician, and political activist (6). He participated in the San Francisco General Strike of 1934 in which the City of San Francisco was shut down when 65,000 workers from all industries walked off from their jobs to demand for more union control toward improved working conditions (7).