Hymenoptera: Formicidae)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ants in French Polynesia and the Pacific: Species Distributions and Conservation Concerns

Ants in French Polynesia and the Pacific: species distributions and conservation concerns Paul Krushelnycky Dept of Plant and Environmental Protection Sciences, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii Hervé Jourdan Centre de Biologie et de Gestion des Populations, INRA/IRD, Nouméa, New Caledonia The importance of ants • In most ecosystems, form a substantial portion of a communities’ biomass (1/3 of animal biomass and ¾ of insect biomass in Amazon rainforest) Photos © Alex Wild The importance of ants • In most ecosystems, form a substantial portion of a communities’ biomass (1/3 of animal biomass and ¾ of insect biomass in Amazon rainforest) • Involved in many important ecosystem processes: predator/prey relationships herbivory seed dispersal soil turning mutualisms Photos © Alex Wild The importance of ants • Important in shaping evolution of biotic communities and ecosystems Photos © Alex Wild Ants in the Pacific • Pacific archipelagoes the most remote in the world • Implications for understanding ant biogeography (patterns of dispersal, species/area relationships, community assembly) • Evolution of faunas with depauperate ant communities • Consequent effects of ant introductions Hypoponera zwaluwenburgi Ants in the Amblyopone zwaluwenburgi Pacific – current picture Ponera bableti Indigenous ants in the Pacific? Approx. 30 - 37 species have been labeled “wide-ranging Pacific natives”: Adelomyrmex hirsutus Ponera incerta Anochetus graeffei Ponera loi Camponotus chloroticus Ponera swezeyi Camponotus navigator Ponera tenuis Camponotus rufifrons -

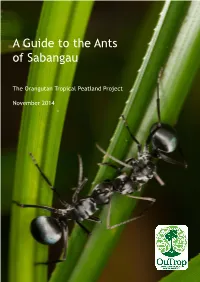

A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau

A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project November 2014 A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau All original text, layout and illustrations are by Stijn Schreven (e-mail: [email protected]), supple- mented by quotations (with permission) from taxonomic revisions or monographs by Donat Agosti, Barry Bolton, Wolfgang Dorow, Katsuyuki Eguchi, Shingo Hosoishi, John LaPolla, Bernhard Seifert and Philip Ward. The guide was edited by Mark Harrison and Nicholas Marchant. All microscopic photography is from Antbase.net and AntWeb.org, with additional images from Andrew Walmsley Photography, Erik Frank, Stijn Schreven and Thea Powell. The project was devised by Mark Harrison and Eric Perlett, developed by Eric Perlett, and coordinated in the field by Nicholas Marchant. Sample identification, taxonomic research and fieldwork was by Stijn Schreven, Eric Perlett, Benjamin Jarrett, Fransiskus Agus Harsanto, Ari Purwanto and Abdul Azis. Front cover photo: Workers of Polyrhachis (Myrma) sp., photographer: Erik Frank/ OuTrop. Back cover photo: Sabangau forest, photographer: Stijn Schreven/ OuTrop. © 2014, The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project. All rights reserved. Email [email protected] Website www.outrop.com Citation: Schreven SJJ, Perlett E, Jarrett BJM, Harsanto FA, Purwanto A, Azis A, Marchant NC, Harrison ME (2014). A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau. The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project, Palangka Raya, Indonesia. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of OuTrop’s partners or sponsors. The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project is registered in the UK as a non-profit organisation (Company No. 06761511) and is supported by the Orangutan Tropical Peatland Trust (UK Registered Charity No. -

Taxonomic Studies on Ant Genus Hypoponera (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Ponerinae) from India

ASIAN MYRMECOLOGY Volume 7, 37 – 51, 2015 ISSN 1985-1944 © HIMENDER BHARTI, SHAHID ALI AKBAR, AIJAZ AHMAD WACHKOO AND JOGINDER SINGH Taxonomic studies on ant genus Hypoponera (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Ponerinae) from India HIMENDER BHARTI*, SHAHID ALI AKBAR, AIJAZ AHMAD WACHKOO AND JOGINDER SINGH Department of Zoology and Environmental Sciences, Punjabi University, Patiala – 147002, India *Corresponding author's e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. The Indian species of the ant genus Hypoponera Santschi, 1938 are treated herewith. Eight species are recognized of which three are described as new and two infraspecific taxa are raised to species level. The eight Indian species are: H. aitkenii (Forel, 1900) stat. nov., H. assmuthi (Forel, 1905), H. confinis (Roger, 1860), H. kashmirensis sp. nov., H. shattucki sp. nov., H. ragusai (Emery, 1894), H. schmidti sp. nov. and H. wroughtonii (Forel, 1900) stat. nov. An identification key based on the worker caste of Indian species is provided. Keywords: New species, ants, Formicidae, Ponerinae, Hypoponera, India. INTRODUCTION genus with use of new taxonomic characters facilitating prompt identification. The taxonomy of Hypoponera has been in a From India, three species and two state of confusion and uncertainty for some infraspecific taxa ofHypoponera have been reported time. The small size of the ants, coupled with the to date (Bharti, 2011): Hypoponera assmuthi morphological monotony has led to the neglect (Forel, 1905), Hypoponera confinis (Roger, of this genus. The only noteworthy revisionary 1860), Hypoponera confinis aitkenii (Forel, 1900), work is that of Bolton and Fisher (2011) for Hypoponera confinis wroughtonii (Forel, 1900) and the Afrotropical and West Palearctic regions. Hypoponera ragusai (Emery, 1894). -

Diversity and Organization of the Ground Foraging Ant Faunas of Forest, Grassland and Tree Crops in Papua New Guinea

- - -- Aust. J. Zool., 1975, 23, 71-89 Diversity and Organization of the Ground Foraging Ant Faunas of Forest, Grassland and Tree Crops in Papua New Guinea P. M. Room Department of Agriculture, Stock and Fisheries, Papua New Guinea; present address: Cotton Research Unit, CSIRO, P.M.B. Myallvale Mail Run, Narrabri, N.S.W. 2390. Abstract Thirty samples of ants were taken in each of seven habitats: primary forest, rubber plantation, coffee plantation, oilpalm plantation, kunai grassland, eucalypt savannah and urban grassland. Sixty samples were taken in cocoa plantations. A total of 156 species was taken, and the frequency of occurrence of each in each habitat is given. Eight stenoecious species are suggested as habitat indicators. Habitats fell into a series according to the similarity of their ant faunas: forest, rubber and coffee, cocoa and oilpalm, kunai and savannah, urban. This series represents an artificial, discontinuous succession from a complex stable ecosystem to a simple unstable one. Availability of species suitably preadapted to occupy habitats did not appear to limit species richness. Habitat heterogeneity and stability as affected by human interference did seem to account for inter-habitat variability in species richness. Species diversity was compared between habitats using four indices: Fisher et al.; Margalef; Shannon; Brillouin. Correlation of diversity index with habitat hetero- geneity plus stability was good for the first two, moderate for Shannon, and poor for Brillouin. Greatest diversity was found in rubber, the penultimate in the series of habitats according to hetero- geneity plus stability ('maturity'). Equitability exceeded the presumed maximum in rubber, and was close to the maximum in all habitats. -

Том 16. Вып. 2 Vol. 16. No. 2

РОССИЙСКАЯ АКАДЕМИЯ НАУК Южный научный центр RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Southern Scientific Centre CAUCASIAN ENTOMOLOGICAL BULLETIN Том 16. Вып. 2 Vol. 16. No. 2 Ростов-на-Дону 2020 Кавказский энтомологический бюллетень 16(2): 381–389 © Caucasian Entomological Bulletin 2020 Contribution of wet zone coconut plantations and non-agricultural lands to the conservation of ant communities (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Sri Lanka © R.K.S. Dias, W.P.S.P. Premadasa Department of Zoology and Environmental Management, Faculty of Science, University of Kelaniya, Kelaniya 11600 Sri Lanka. E-mails: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. Agricultural practices are blamed for the reduction of ant diversity on earth. Contribution of four coconut plantations (CP) and four non-agricultural lands (NL) for sustaining diversity and relative abundance of ground-dwelling and ground-foraging ants was investigated by surveying them from May to October, 2018, in a CP and a NL in Minuwangoda, Mirigama, Katana and Veyangoda in Gampaha District that lies in the wet zone, Sri Lanka. Worker ants were surveyed by honey baiting and soil sifting along two transects at three, 50 m2 plots in each type of land. Workers were identified using standard methods and frequency of each ant species observed by each method was recorded. Percentage frequency of occurrence observed by each method, mean percentage frequency of occurrence of each ant species and proportional abundance of each species in each ant community were calculated. Species richness recorded by both methods at each CP was 14–19 whereas that recorded at each NL was 17–23. Shannon-Wiener Diversity Index values (Hʹ, CP: 2.06–2.36; NL: 2.11–2.56) and Shannon- Wiener Equitability Index values (Jʹ, CP: 0.73–0.87; NL: 0.7–0.88) showed a considerable diversity and evenness of ant communities at both types of lands. -

Ecological Partitioning and Invasive Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a Tropical Rain Forest Ant Community from Fiji1

Ecological Partitioning and Invasive Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a Tropical Rain Forest Ant Community from Fiji1 Darren Ward2 Abstract: Determining composition and structure of ant communities may help understand how niche opportunities become available for invasive ant species and ultimately how communities are invaded. This study examined composition and structure of an ant community from a tropical rain forest in Fiji, specifically looking at spatial partitioning and presence of invasive ant species. A total of 27 species was collected, including five invasive species. Spatial partitioning be- tween arboreal (foliage beating) and litter (quadrat) samples was evident with a relatively low species overlap and a different composition of ant genera. Com- position and abundance of ants was also significantly different between litter and arboreal microhabitats at baits, but not at different bait types (oil, sugar, tuna). In terms of invasive ant species, there was no difference in number of invasive species between canopy and litter. However, the most common species, Paratre- china vaga, was significantly less abundant and less frequently collected in the canopy. In arboreal samples, invasive species were significantly smaller than en- demic species, which may have provided an opportunity for invasive species to become established. However, taxonomic disharmony (missing elements in the fauna) could also play an important role in success of invasive ant species across the Pacific region. Invasive ants represent a serious threat to biodiversity in Fiji and on many other Pacific islands. A greater understanding of habitat suscepti- bility and mechanisms for invasion may help mitigate their impacts. Explaining and predicting the success of 1999, Holway et al. -

Ants (Hymenoptera: Fonnicidae) of Samoa!

Ants (Hymenoptera: Fonnicidae) of Samoa! James K Wetterer 2 and Donald L. Vargo 3 Abstract: The ants of Samoa have been well studied compared with those of other Pacific island groups. Using Wilson and Taylor's (1967) specimen records and taxonomic analyses and Wilson and Hunt's (1967) list of 61 ant species with reliable records from Samoa as a starting point, we added published, unpublished, and new records ofants collected in Samoa and updated taxonomy. We increased the list of ants from Samoa to 68 species. Of these 68 ant species, 12 species are known only from Samoa or from Samoa and one neighboring island group, 30 species appear to be broader-ranged Pacific natives, and 26 appear to be exotic to the Pacific region. The seven-species increase in the Samoan ant list resulted from the split of Pacific Tetramorium guineense into the exotic T. bicarinatum and the native T. insolens, new records of four exotic species (Cardiocondyla obscurior, Hypoponera opaciceps, Solenopsis geminata, and Tetramorium lanuginosum), and new records of two species of uncertain status (Tetramorium cf. grassii, tentatively considered a native Pacific species, and Monomorium sp., tentatively considered an endemic Samoan form). SAMOA IS AN ISLAND CHAIN in western island groups, prompting Wilson and Taylor Polynesia with nine inhabited islands and (1967 :4) to feel "confident that a nearly numerous smaller, uninhabited islands. The complete faunal list could be made for the western four inhabited islands, Savai'i, Apo Samoan Islands." Samoa is of particular in lima, Manono, and 'Upolu, are part of the terest because it is one of the easternmost independent country of Samoa (formerly Pacific island groups with a substantial en Western Samoa). -

Taxonomic Classification of Ants (Formicidae)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/407452; this version posted September 4, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Taxonomic Classification of Ants (Formicidae) from Images using Deep Learning Marijn J. A. Boer1 and Rutger A. Vos1;∗ 1 Endless Forms, Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden, 2333 BA, Netherlands *[email protected] Abstract 1 The well-documented, species-rich, and diverse group of ants (Formicidae) are important 2 ecological bioindicators for species richness, ecosystem health, and biodiversity, but ant 3 species identification is complex and requires specific knowledge. In the past few years, 4 insect identification from images has seen increasing interest and success, with processing 5 speed improving and costs lowering. Here we propose deep learning (in the form of a 6 convolutional neural network (CNN)) to classify ants at species level using AntWeb 7 images. We used an Inception-ResNet-V2-based CNN to classify ant images, and three 8 shot types with 10,204 images for 97 species, in addition to a multi-view approach, for 9 training and testing the CNN while also testing a worker-only set and an AntWeb 10 protocol-deviant test set. Top 1 accuracy reached 62% - 81%, top 3 accuracy 80% - 92%, 11 and genus accuracy 79% - 95% on species classification for different shot type approaches. 12 The head shot type outperformed other shot type approaches. -

Of Christmas Island (Indian Ocean): Identification and Distribution

DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.25(1).2008.045-085 Records of the Western Australian Museum 25: 45-85 (2008). Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Christmas Island (Indian Ocean): identification and distribution Volker w. Framenau1,2 andMelissa 1. Thomas2,3,* 1 Department of Terrestrial Zoology, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] 2 School of Animal Biology, University of Western Australia, Crawley, Western Australia 6009, Australia. 3 Parks Australia North, PO Box 867, Christmas Island, Indian Ocean 6798, Australia. Abstract - The composition of the Christmas Island (Indian Ocean) ant fauna is reviewed, leading to the recognition of 52 species in 24 genera and 7 subfamilies. This account amalgamates previously published records and recent extensive surveys of Christmas Island's ant fauna. Eight species represent new records for Christmas Island: Technomyrmex vitiensis, Camponotus sp. (novaehollandiae group), Cardiocondyla kagutsuchi, Monomorium orientale, M. cf. subcoecum, Tetramorium cf. simillimum, T. smithi and T. walshi. Although some of these new species records represent recent taxonomic advances rather than new introductions, we consider four species to be true new records to Christmas Island. These include Camponotus sp. (novaehollandiae group), M. orientale, T. smithi and T. walshi. None of the 52 species reported here are considered endemic. In general, the Christmas Island ant fauna is composed of species that are regarded as worldwide tramps, or that are widespread in the Indo-Australian region. However, Christmas Island may fall within the native range of some of these species. We provide a key to the ant species of Christmas Island (based on the worker caste), supplemented by comprehensive distribution maps of these ants on Christmas Island and a short synopsis of each species in relation to their ecology and world-wide distribution. -

Actes Des Colloques Insectes Sociaux

U 2 I 0 E 0 I 2 S ACTES DES COLLOQUES INSECTES SOCIAUX Edité par l'Union Internationale pour l’Etude des Insectes Sociaux - Section française (sous la direction de François-Xavier DECHAUME MONCHARMONT et Minh-Hà PHAM-DELEGUE) VOL. 15 (2002) – COMPTE RENDU DU COLLOQUE ANNUEL 50e anniversaire - Versailles - 16-18 septembre 2002 ACTES DES COLLOQUES INSECTES SOCIAUX Edité par l'Union Internationale pour l’Etude des Insectes Sociaux - Section française (sous la direction de François-Xavier DECHAUME MONCHARMONT et Minh-Hà PHAM-DELEGUE) VOL. 15 (2002) – COMPTE RENDU DU COLLOQUE ANNUEL 50e anniversaire - Versailles - 16-18 septembre 2002 ISSN n° 0265-0076 ISBN n° 2-905272-14-7 Composé au Laboratoire de Neurobiologie Comparée des Invertébrés (INRA, Bures-sur-Yvette) Publié on-line sur le site des Insectes Sociaux : : http://www.univ-tours.fr/desco/UIEIS/UIEIS.htm Comité Scientifique : Martin GIURFA Université Toulouse Alain LENOIR Université Tours Christian PEETERS CNRS Paris 6 Minh-Hà PHAM-DELEGUE INRA Bures Comité d'Organisation : Evelyne GENECQUE F.X. DECHAUME MONCHARMONT Et toute l’équipe du LNCI (INRA Bures) Nous remercions sincèrement l’INRA et l’établissement THOMAS qui ont soutenu financièrement cette manifestation. Crédits Photographiques Couverture : 1. Abeille : Serge CARRE (INRA) 2. Fourmis : Photothèque CNRS 3. Termite : Alain ROBERT (Université de Bourgogne, Dijon) UIEIS Versailles Page 1 Programme UNION INTERNATIONALE POUR L’ETUDE DES INSECTES SOCIAUX UIEIS Section Française - 50ème Anniversaire Versailles 16-18 Septembre 2002 PROGRAMME Lundi 16 septembre 9 h ACCUEIL DES PARTICIPANTS - CAFE 10 h Présentation du Centre INRA de Versailles – Président du Centre Session Plasticité et Socialité- Modérateur Martin Giurfa 10 h 15 - Conférence Watching the bee brain when it learns – Randolf Menzel (Université Libre de Berlin) 11 h 15 Calcium responses to queen pheromones, social pheromones and plant odours in the antennal lobe of the honey bee drone Apis mellifera L. -

Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae)

INS. KOREANA, 18(3): 000~000. September 30, 2001 Review of Korean Dacetini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae) Dong-Pyeo LYU, Byeong-MOON CHOI1) and Soowon CHO Department of Agricultural Biology, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, CB 361-763, Korea 1) Dept. of Science Education, Cheongju National University of Education, Cheongju, CB 361-150, Korea Abstract Most current systematic changes in the tribe Dacetini are applied to the Korean dacetine ants. The tribe Dacetini of Korea include Strumigenys lewisi, Pyramica incerta, P. japonica, P. mutica, and P. hexamerus. Taxonomic positions are revised, new informations are added, and a full reference list is provided. Key words Strumigenys lewisi, Pyramica incerta, P. japonica, P. mutica, P. hexamerus, Dacetini, Formicidae, Korea INTRODUCTION The Dacetini is a tribe of ants that are all predators, most of them small, cryptic elements of tropical forest leaf litter and rotten wood (Bolton, 1998). Most of them have highly modified mandibles, being different from the standard triangular mandible common to most other ants. Many have mandibles that are elongate, linear, and with opposing tines at the tip. Others have elongate mandibles like serrated scissors, or have serrated mandibles that are curved ventrally. For some time, the name Dacetini had been confused with Dacetonini. The tribe name was originated from the genus Daceton, but the genitive of daketon (“biter”) would be daketou, so the tribe name must be Dacetini, not Dacetonini. Bolton (2000) also recently found this problem and he resurrected the name Dacetini. The generic classification of the tribe up to now is the product of a series of revisionary papers mainly by Brown (1948, 1949a, b, c, 1950a, b, 1952b, 1953a, 1954a), Brown and Wilson (1959) and Brown and Carpenter (1979). -

Bauxite Mining Restoration with Natural Soils and Residue Sands: Comparison of the Recovery of Soil Ecosystem Function and Ground-Dwelling Invertebrate Diversity

School of Molecular and Life Sciences Bauxite Mining Restoration with Natural Soils and Residue Sands: Comparison of the Recovery of Soil Ecosystem Function and Ground-dwelling Invertebrate Diversity Dilanka Madusani Mihindukulasooriya Weerasinghe This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University May 2019 Author’s Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief, this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgement has been made. This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature………………………………………………… Date………………………………………………………... iii Statement of authors’ contributions Experimental set up, data collection, data analysis and data interpretation for Chapter 2, 3,4 and 5 was done by D. Mihindukulasooriya. Experimental set up established by Lythe et al. (2017) used for experimental chapter 6. Data collection, data analysis and data interpretation for long term effect of woody debris addition was done by D. Mihindukulasooriya. iv Abstract Human destruction of the natural environment has been identified as a global problem that has triggered the loss of biodiversity. This degradation and loss has altered ecosystem processes and the resilience of ecosystems to environmental changes. Restoration of degraded habitats forms a significant component of conservation efforts. Open cut mining is one activity that can dramatically alter local communities, and successful vascular plant restoration does not necessarily result in restoration of other components of flora and fauna or result in a fully functioning ecosystem. Therefore, restoration studies should focus on improving ecological functions such as nutrient cycling and litter decomposition, seed dispersal and/ or pollination, and assess community composition beyond vegetation to attain fully functioning systems.