Fair Deals for Watershed Services in South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Drug Master Plan 2013 – 2017 and the Work Done by the Inter- Ministerial Committee on Alcohol and Substance Abuse Seek to Address These Challenges

NATIONAL DRUG MASTER PLAN 2013 – 2017 FOREWORD BY THE MINISTER OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT The impact of alcohol and substance abuse continues to ravage families, communities and society. The youth of South Africa are particularly hard hit due to increases in the harmful use of alcohol and the use and abuse of illicit drugs. The use of alcohol and illicit drugs impact negatively on the users, their families and communities. Alcohol and drugs damage the health of users and are linked to rises in non-communicable diseases including HIV and AIDS, cancer, heart disease and psychological disorders. Users are also exposed to violent crime, either as perpetrators or victims and are also at risk of long-term unemployment due to school dropout and foetal alcohol syndrome, being in conflict with law and loss of employment. The social costs for users are exacerbated due to being ostracised from families and their communities. In acute cases users are at risk of premature deaths due ill health, people involved in accidents as well as innocent drivers, violent crime and suicide. The harmful use of alcohol and drugs exposes non-users to injury and death due to people driving under the influence of alcohol and drugs and through being victims of violent crime. Socially, the families of addicts are placed under significant financial pressures due to the costs associated with theft from the family, legal fees for users and the high costs of treatment. The emotional and psychological impacts on families and the high levels of crime and other social ills have left many communities under siege by the scale of alcohol and drug abuse. -

Sabie 109Tt Presentation August 2014

INDEX 1. INTRODUCTION 11. VALUABLE SUPPORTING INFORMATION 2. THE SABIE 109TT 12. TOURIST ACTIVITY AND INVESTMENT 3. THE ISLE OF MAN TT 13. TOURIST ACTIVITY 2017 AND ONWARDS 4. MOTIVATION FOR THE SABIE 109TT 14. IN TIME TO FOLLOW 5. THE COMPANY 15. EXPOSURE FOR THE PROVINCE AND REGION 6. THE ROAD TO THE SABIE 109TT 16. COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT 7. ADVANTAGES 17. THE SABIE 109TT LEGACY 8. EVENTS 18. GOVERNMENT 9. CRUCIAL FACTORS ASSISTANCE REQUIRED 19. THE VISION 10. PROJECTED 22TT INCOME 20. LINKS TO THE ISLE OF MAN TT VIDEOS 1. INTRODUCTION In the past worthwhile “signature events” brought fame and fortune to countries, provinces and cities all over the world. Modern times with its competition on all fronts and increasing entertainment options make it very difficult to find a place in the sun for any new activity, and it is not easy to create such events without simply copying another event. Our aim was to find an event that would stand out and live up to the challenge of becoming a Signature event for Mpumalanga. This presentation tells you more. 2. THE SABIE 109TT This will be an event based on international proven results that will, combined with local vision and drive, create a Signature event for Mpumalanga. Chances are that it will become one of the best and most exciting South African Sporting events, ever! This event will be based on a world-renowned motorcycle race, held annually for more than a century on the Isle of Man. 3. THE ISLE OF MAN TT The Isle of Man TT is a race for motorcycles that has been running since 1907. -

U–Pb Zircon (SHRIMP) Ages for the Lebombo Rhyolites, South Africa

Journal of the Geological Society, London, Vol. 161, 2004, pp. 547–550. Printed in Great Britain. 2000) and the ages corroborate and further strengthen the SPECIAL chronology of the Lebombo stratigraphy. The rapid eruption of the Karoo succession is thought to have been responsible for trigger- U–Pb zircon (SHRIMP) ing the early Toarcian extinction event (Hesselbo et al. 2000). Geological setting. The Karoo Supergroup succession along the ages for the Lebombo Lebombo monocline is highlighted in Figure 1. The oldest phase of Karoo volcanism is marked by the Mashikiri nephelinites, rhyolites, South Africa: which unconformably overlie Jurassic Clarens Formation sand- stones (Fig. 2). The nephelinites have been dated at 182.1 Æ refining the duration of 1.6 Ma (40Ar/39Ar plateau age; Duncan et al. 1997) and form a lava succession up to 170 m thick (Bristow 1984). These rocks Karoo volcanism are confined to the northern part of the Lebombo rift and are absent along the central and southern sections. The nephelinites T. R. RILEY1,I.L.MILLAR2, are conformably overlain by picrites and picritic basalts of the 3 1 Letaba Formation, although in the southern Lebombo the picrites M. K. WATKEYS ,M.L.CURTIS, directly overlie the Clarens Formation. The picrites overlap in 1 3 P. T. LEAT , M. B. KLAUSEN & age (182.7 Æ 0.8 Ma; Duncan et al. 1997) with the Mashikiri C. M. FANNING4 nephelinites and are believed to form a succession up to 4 km in thickness. 1British Antarctic Survey, High Cross, Madingley Road, The Letaba Formation picrites are in turn overlain by a major Cambridge, CB3 0ET, UK (e-mail: [email protected]) succession (4–5 km thick) of low-MgO basalts, termed the Sabie 2British Antarctic Survey c/o NERC Isotope Geosciences River Basalt Formation (Cleverly & Bristow 1979). -

Final Policy Paper

Eve Gray ACHIEVING RESEARCH IMPACT FOR DEVELOPMENT A Critique of Research Dissemination Policy in South Africa, with Recommendations for Policy Reform Open Society Institute International Policy Fellowship Programme 2006-7 This policy paper was produced as the outcome of the OSI 2006-07 International Policy Fellowship programme. Eve Gray was a member of the Open Information Policy working group, which was directed by Lawrence Liang. More details of the policy research of the Open Information Working Group can be found at http://www.policy.hu/themes06/opinfo/index.html This report is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution, non-Commercial, No Derivative Works licence http://www.creativecommons.org The views contained in this report remain solely those of the author, who may be contacted at [email protected]. For a fuller account of this policy research project, please visit http://www.policy.hu/gray . International Policy Fellowship Program Open Society Institute Nador Utca 9 Budpest 1051 Hungary http://www.policy.hu ABSTRACT This paper reviews the policy context for research publication in South Africa, using South Africa’s relatively privileged status as an African country and its elaborated research policy environment as a testing ground for what might be achieved – or what needs to be avoided - in other African countries. The policy review takes place against the background of a global scholarly publishing system in which African knowledge is seriously marginalised and is poorly represented in global scholarly output. Scholarly publishing policies that drive the dissemination of African research into international journals that are not accessible in developing countries because of their high cost effectively inhibit the ability of relevant research to impact on the overwhelming development challenges that face the continent. -

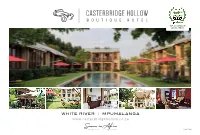

Casterbridge-Fact-Sheet.Pdf

TOP 25 HOTELS IN SOUTH AFRICA WHITE RIVER I MPUMALANGA www.casterbridgehollow.co.za AUGUST 2019 Pilgrim’sGRASKOP Rest R535 Graskop HAZYVIEW R536 Hazyview Kruger National Park MOZAMBIQUE LIMPOPO PROVINCE KRUGER BOTSWANA Skukuza NATIONAL CASTERBRIDGE SABIE PARK HOLLOW R40 Johannesburg Sabie R538 NAMIBIA NORTH WEST PROVINCE GAUTENG MPUMALANGA Pretoriuskop SWAZILAND R37 R537 FREE STATE KWAZULU- NATAL White River LESOTHO KRUGER NORTHERN CAPE WHITE RIVER Casterbridge Lifestyle Centre Durban NATIONAL PLASTON PARK EASTERN CAPE R37 KMIA Kruger Mpumalanga R40 International Airport WESTERN CAPE Cape Town N4 NELSPRUIT N4 R40 WHITE RIVER I MPUMALANGA Casterbridge, once a spreading Mango plantation in White River, has been transformed into one of the most original and enchanting country estates in South Africa. Just 20 km from Nelspruit, a mere 40 km from Hazyview and Sabie; White River has become home to a host of creative talents; artists, designers, fine craftsmen, ceramicists, cooks and restaurateurs. Casterbridge Hollow is a concept that has evolved with great charm with colours reminiscent of romantic hillside villages in Provence and Tuscany. LOCATION • Casterbridge Hollow Boutique Hotel is situated outside White River. • It is the ideal destination from which to access the reserves of the Lowveld and the attractions of Mpumalanga. ACCOMMODATION 30 ROOMS • 24 Standard, 2 Honeymoon and 4 Family • Air-conditioning and heating • Ceiling fans • Balconies overlook the courtyard and swimming pool • Satellite television • Tea / coffee making facilities -

Insights from the Kruger National Park, South Africa

Morphodynamic response of a dryland river to an extreme flood Morphodynamics of bedrock-influenced dryland rivers during extreme floods: Insights from the Kruger National Park, South Africa David Milan1,†, George Heritage2, Stephen Tooth3, and Neil Entwistle4 1School of Environmental Sciences, University of Hull, Cottingham Road, Hull, HU6 7RX, UK 2AECOM, Exchange Court, 1 Dale Street, Liverpool, L2 2ET, UK 3 Department of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Llandinam Building, Penglais Campus, Aberystwyth, SY23 3DB, UK 4School of Environment and Life Sciences, Peel Building, University of Salford, Salford, M5 4WT, UK ABSTRACT some subreaches, remnant islands and vege- the world’s population (United Nations, 2016). tation that survived the 2000 floods were re- Drylands are characterized by net annual mois- High-magnitude flood events are among moved during the smaller 2012 floods owing ture deficits resulting from low annual precipita- the world’s most widespread and signifi- to their wider exposure to flow. These find- tion and high potential evaporation, and typically cant natural hazards and play a key role in ings were synthesized to refine and extend a by strong climatic variability. Although precipi- shaping river channel–floodplain morphol- conceptual model of bedrock-influenced dry- tation regimes vary widely, many drylands are ogy and riparian ecology. Development of land river response that incorporates flood subject to extended dry periods and occasional conceptual and quantitative models for the sequencing, channel type, and sediment sup- intense rainfall events. Consequently, dryland response of bedrock-influenced dryland ply influences. In particular, with some cli- rivers are commonly defined by long periods rivers to such floods is of growing scientific mate change projections indicating the po- with very low or no flow, interspersed with in- and practical importance, but in many in- tential for future increases in the frequency frequent, short-lived, larger flows. -

The Mineral Industries of Africa in 2005

2005 Minerals Yearbook AFRICA U.S. Department of the Interior August 2007 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUSTRIES OF AFRICA By Thomas R. Yager, Omayra Bermúdez-Lugo, Philip M. Mobbs, Harold R. Newman, and David R. Wilburn The 55 independent nations and other territories of continental • Uganda—Department of Geological Survey and Mines, and Africa and adjacent islands covered in this volume encompass a • Zimbabwe—Chamber of Mines. land area of 30.4 million square kilometers, which is more than For basic economic data—the International Monetary Fund in three times the size of the United States, and were home to 896 the United States. million people in 2005. For many of these countries, mineral For minerals consumption data— exploration and production constitute significant parts of their • British Petroleum plc, economies and remain keys to future economic growth. Africa is • Department of Minerals and Energy of the Republic of richly endowed with mineral reserves and ranks first or second South Africa, in quantity of world reserves of bauxite, cobalt, industrial • MEPS (International) Ltd., and diamond, phosphate rock, platinum-group metals (PGM), • U.S. Department of Energy in the United States. vermiculite, and zirconium. For exploration and other mineral-related information—the The mineral industry was an important source of export Metals Economics Group (MEG) in Canada. earnings for many African nations in 2005. To promote exports, groups of African countries have formed numerous trade blocs, General Economic Conditions which included the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, the Economic and Monetary Community of Central In 2005, the real gross domestic product (GDP) of Africa Africa, the Economic Community of Central African States, the grew by 5.4% after increasing by 5.5% in 2004. -

The Geology and Geochemistry of the Sterkspruit Intrusion, Barberton Mountain Land, Mpumalanga Province

THE GEOLOGY AND GEOCHEMISTRY OF THE STERKSPRUIT INTRUSION, BARBERTON MOUNTAIN LAND, MPUMALANGA PROVINCE Gavin Patrick Conway A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Science, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science. Johannesburg, 1997 11 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation is my own, unaided work. It is being submitted for the Degree of Master of Science in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination in any other University. __I_It __ ·daYOf A~V\.-~t 19 't1-- 111 ABSTRACT The Sterkspruit Intrusion, in the south-western portion of the Barberton greenstone belt, is a sill-like body containing rocks of gabbroic to dioritic composition. It is hosted by a sequence of komatiitic basalts and komatiites of the Lower Onverwacht Group. The intrusion is considered unique in this area in that it lacks ultramafic components and has no affinities with the surrounding mafic- to- ultramafic lavas. The gabbroic suite also contains an unusual abundance of quartz, and the chill margin shows an evolved quartz-normative, tholeiitic parental magma. Based on petrographic and geochemical evidence, the intrusion can be subdivided into four gabbroic zones and a quartz diorite, which is an end product of a differentiating magma. The chill margin records an MgO content of 4.8%, an Mg# of 42, an Si02 value of 52.5% and a normative plagioclase composition of An 44. The sill-like nature of the body, indicated by geochemical trends, and the steep sub-vertical layering, point to a body that has been tilted along with the surrounding lavas. -

An Ecological Study of the Plant Communities in the Proposed Highveld Published: 26 Apr

An ecological study of the plant communities in the proposed Highveld National Park Original Research An ecologicAl study of the plAnt communities in the proposed highveld nAtionAl pArk, in the peri-urbAn AreA of potchefstroom, south AfricA Authors: Mahlomola E. Daemane1 ABSTRACT Sarel S. Cilliers2 The proposed Highveld National Park (HNP) is an area of high conservation value in South Hugo Bezuidenhout1 Africa, covering approximately 0.03% of the endangered Grassland Biome. The park is situated immediately adjacent to the town of Potchefstroom in the North-West Province. The objective of Affiliations: this study was to identify, classify, describe and map the plant communities in this park. Vegetation 1Conservation Services sampling was done by means of the Braun-Blanquet method and a total of 88 stratified random Department, South African relevés were sampled. A numerical classification technique (TWINSPAN) was used and the results National Parks, were refined by Braun-Blanquet procedures. The final results of the classification procedure were South Africa presented in the form of phytosociological tables and, thereafter, nine plant communities were described and mapped. A detrended correspondence analysis confirmed the presence of three 2School of Environmental structural vegetation units, namely woodland, shrubland and grassland. Differences in floristic Sciences and composition in the three vegetation units were found to be influenced by environmental factors, Development, North-West such as surface rockiness and altitude. Incidences of harvesting trees for fuel, uncontrolled fires University, South Africa and overgrazing were found to have a significant effect on floristic and structural composition in the HNP. The ecological interpretation derived from this study can therefore be used as a tool for Correspondence to: environmental planning and management of this grassland area. -

Mangrove Kingfisher in South Africa, but the Species Overlap Further North in Mozam- Bique, and Hybridization May Occur (Hanmer 1984A, 1989C)

652 Halcyonidae: kingfishers Habitat: It occurs in summer along the banks of forested rivers and streams, at or near the coast. In winter it occurs in stands of mangroves, along wooded lagoons and even in suburban gardens and parks, presumably while on mi- gration. Elsewhere in Africa it may occur in woodlands further away from water. Movements: The models show that it occurs in the Transkei (mainly Zone 8) in summer and is absent June– August, while it is absent or rarely reported November– March in KwaZulu-Natal, indicating a seasonal movement between the Transkei and KwaZulu-Natal. Berruti et al. (1994a) analysed atlas data to document this movement in more detail. The atlas records for the Transkei confirm earlier reports in which the species was recorded mainly in summer with occasional breeding records (Jonsson 1965; Pike 1966; Quickelberge 1989; Cooper & Swart 1992). In KwaZulu-Natal, it was previously regarded as a breeding species which moved inland to breed, despite the fact that nearly all records are from the coast in winter (Clancey 1964b, 1965d, 1971c; Cyrus & Robson 1980; Maclean 1993b), and there were no breeding records (e.g. Clancey 1965d; Dean 1971). However, it is possible that it used to be a rare breeding species in KwaZulu-Natal (Clancey 1965d). The atlas and other available data clearly show that it is a nonbreeding migrant to KwaZulu-Natal from the Transkei. Clancey (1965d) suggested that most movement took place in March. Berruti et al. (1994a) showed that it apparently did not overwinter in KwaZulu- Natal south of Durban (2931CC), presumably because of the lack of mangroves in this area. -

Our Glorious AFS Itinerary Jun 17 Air Is

Our Glorious AFS Itinerary Jun 17 Air is so easy round-trip to Jo’burg (JNB)! Full details to come on this in AFS Trip Tips with info about flights, overnight options, packing, etc. We urge you to fly in a day early to arrive Jun 18. Full details to come on all air options, overnight options and packing in AFS trips tips. Day 1: Fri, Jun 19 Chisomo Safari Camp, Kruger Private Reserves Our land tour officially begins! We gather early morning at JNB Airport and fly an hour to Kruger. We arrive in time for lunch and a short rest before heading out on your first afternoon game drive. South Africa This vast country is undoubtedly one of the most culturally and geographically diverse places on earth. Fondly known by locals as the 'Rainbow Nation', South Africa has 11 official languages and its multicultural inhabitants are influenced by a fascinating mix of cultures. Discover the gourmet restaurants, impressive art scene, vibrant nightlife and beautiful beaches of Cape Town; enjoy a local braai (barbecue) in the Soweto Township; browse the bustling Indian markets in Durban; or sample some of the world’s finest wines at the myriad wine estates dotting the Cape Winelands. Some historical attractions to explore include the Zululand battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal, the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg and Robben Island, just off the coast of Cape Town. Above all else, its remarkably untamed wilderness with its astonishing range of wildlife roaming freely across massive unfenced game reserves such as the world-famous Kruger National Park. With all of this variety on offer, it is little wonder that South Africa has fast become Africa’s most popular tourist destination. -

South African Biosphere Reserve National Committee

SOUTH AFRICAN BIOSPHERE RESERVE NATIONAL COMMITTEE BIENNIAL REPORT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF LIMA ACTION PLAN UNESCO MAN AND BIOSPHERE PROGRAMME ICC INTERNATIONAL COORDINATING COUNCIL 31ST SESSION, PARIS, FRANCE 17-21 JUNE 2019 JUNE 2019 1. BACKGROUND 1.1 Coordination of Man and Biosphere Programme South Africa has started participating in the Man and Biosphere (MAB) Programme since 1995 at the Seville Conference in Spain. The South African National Biosphere Reserve Committee (SA BR NATCOM), which is chaired by the National Department of Environmental Affairs coordinates the Man and Biosphere Programme in South Africa. The SA MAB NATCOM is financially supported by the National Department of Environmental Affairs. The SA MAB NATCOM is operational in accordance with the Lima Action Plan and is comprised of representatives from National, Provincial, local, Non-Profit Organisations and research institutions. SA National BR Committee has met once since the previous MAB ICC Session, in June 2018. South Africa is the current member of the MAB International Coordinating Committee (ICC) elected in November 2017 and also a member of the African Network of Man and Biosphere (AfriMAB) Bureau as coordinator for Southern Africa sub-region, elected in September 2017. The provinces supports Biosphere Reserves with operational funding. At the local level, there are Biosphere Reserve Forum, which meets on quarterly basis. These Forums are comprised of Provincial Government, Local Government, Non-Governmental Organizations and Biosphere