River Flow and Quality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insights from the Kruger National Park, South Africa

Morphodynamic response of a dryland river to an extreme flood Morphodynamics of bedrock-influenced dryland rivers during extreme floods: Insights from the Kruger National Park, South Africa David Milan1,†, George Heritage2, Stephen Tooth3, and Neil Entwistle4 1School of Environmental Sciences, University of Hull, Cottingham Road, Hull, HU6 7RX, UK 2AECOM, Exchange Court, 1 Dale Street, Liverpool, L2 2ET, UK 3 Department of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Llandinam Building, Penglais Campus, Aberystwyth, SY23 3DB, UK 4School of Environment and Life Sciences, Peel Building, University of Salford, Salford, M5 4WT, UK ABSTRACT some subreaches, remnant islands and vege- the world’s population (United Nations, 2016). tation that survived the 2000 floods were re- Drylands are characterized by net annual mois- High-magnitude flood events are among moved during the smaller 2012 floods owing ture deficits resulting from low annual precipita- the world’s most widespread and signifi- to their wider exposure to flow. These find- tion and high potential evaporation, and typically cant natural hazards and play a key role in ings were synthesized to refine and extend a by strong climatic variability. Although precipi- shaping river channel–floodplain morphol- conceptual model of bedrock-influenced dry- tation regimes vary widely, many drylands are ogy and riparian ecology. Development of land river response that incorporates flood subject to extended dry periods and occasional conceptual and quantitative models for the sequencing, channel type, and sediment sup- intense rainfall events. Consequently, dryland response of bedrock-influenced dryland ply influences. In particular, with some cli- rivers are commonly defined by long periods rivers to such floods is of growing scientific mate change projections indicating the po- with very low or no flow, interspersed with in- and practical importance, but in many in- tential for future increases in the frequency frequent, short-lived, larger flows. -

Towards a Socio-Ecological Systems View of the Sand River Catchment, South Africa

Towards a Socio-Ecological Systems View of the Sand River Catchment, South Africa An Exploratory Resilience Analysis by Sharon Pollard1 2 Harry Biggs 1 Derick du Toit 1 Association for Water and Rural Development (AWARD), Acornhoek 2 SanParks, Scientific Services, Skukuza WRC Report No TT 364/08 OCTOBER 2008 Obtainable from: [email protected] Water Research Commission Private Bag X03 Gezina Pretoria 0031 The publication of this report emanates from a project entitled: Towards a socio-ecological systems view of the Sand River Catchment, South Africa: A resilience analysis of the socio- ecological system (WRC Consultancy No. K8/591). DISCLAIMER This report has been reviewed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the WRC, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. ISBN 978-1-77005-747-0 Printed in the Republic of South Africa Acknowledgements We had the benefit of a visit by Dr Allison (to SANParks Skukuza for several weeks) and were able to discuss the basic aspirations behind this proposal and obtain her input – for which she is thanked here. The Water Research Commission is gratefully acknowledged for financial support. Assistance to the project was given by Oonsie Biggs and Duan Biggs Participants of the specialist workshop are thanked. They included: Tessa Cousins Prof Kevin Rogers Prof Sakkie Niehaus Dr Sheona Shackleton Dr Wayne Twine Duan Biggs -

Our Glorious AFS Itinerary Jun 17 Air Is

Our Glorious AFS Itinerary Jun 17 Air is so easy round-trip to Jo’burg (JNB)! Full details to come on this in AFS Trip Tips with info about flights, overnight options, packing, etc. We urge you to fly in a day early to arrive Jun 18. Full details to come on all air options, overnight options and packing in AFS trips tips. Day 1: Fri, Jun 19 Chisomo Safari Camp, Kruger Private Reserves Our land tour officially begins! We gather early morning at JNB Airport and fly an hour to Kruger. We arrive in time for lunch and a short rest before heading out on your first afternoon game drive. South Africa This vast country is undoubtedly one of the most culturally and geographically diverse places on earth. Fondly known by locals as the 'Rainbow Nation', South Africa has 11 official languages and its multicultural inhabitants are influenced by a fascinating mix of cultures. Discover the gourmet restaurants, impressive art scene, vibrant nightlife and beautiful beaches of Cape Town; enjoy a local braai (barbecue) in the Soweto Township; browse the bustling Indian markets in Durban; or sample some of the world’s finest wines at the myriad wine estates dotting the Cape Winelands. Some historical attractions to explore include the Zululand battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal, the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg and Robben Island, just off the coast of Cape Town. Above all else, its remarkably untamed wilderness with its astonishing range of wildlife roaming freely across massive unfenced game reserves such as the world-famous Kruger National Park. With all of this variety on offer, it is little wonder that South Africa has fast become Africa’s most popular tourist destination. -

Ecological Suitability Modeling for Anthrax in the Kruger National Park, South Africa

RESEARCH ARTICLE Ecological suitability modeling for anthrax in the Kruger National Park, South Africa Pieter Johan Steenkamp1, Henriette van Heerden2*, Ockert Louis van Schalkwyk2¤ 1 University of Pretoria, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Department of Production Animal Studies, Onderstepoort, South Africa, 2 University of Pretoria, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Department of Veterinary Tropical Diseases, Onderstepoort, South Africa ¤ Current address: Office of the State Veterinarian, Skukuza, South Africa * [email protected] Abstract a1111111111 The spores of the soil-borne bacterium, Bacillus anthracis, which causes anthrax are highly a1111111111 resistant to adverse environmental conditions. Under ideal conditions, anthrax spores can a1111111111 a1111111111 survive for many years in the soil. Anthrax is known to be endemic in the northern part of a1111111111 Kruger National Park (KNP) in South Africa (SA), with occasional epidemics spreading southward. The aim of this study was to identify and map areas that are ecologically suitable for the harboring of B. anthracis spores within the KNP. Anthrax surveillance data and selected environmental variables were used as inputs to the maximum entropy (Maxent) OPEN ACCESS species distribution modeling method. Anthrax positive carcasses from 1988±2011 in KNP (n = 597) and a total of 40 environmental variables were used to predict and evaluate their Citation: Steenkamp PJ, van Heerden H, van Schalkwyk OL (2018) Ecological suitability relative contribution to suitability for anthrax occurrence in KNP. The environmental vari- modeling for anthrax in the Kruger National Park, ables that contributed the most to the occurrence of anthrax were soil type, normalized dif- South Africa. PLoS ONE 13(1): e0191704. https:// ference vegetation index (NDVI) and precipitation. -

SANDF Control of the Northern and Eastern Border Areas of South Africa Ettienne Hennop, Arms Management Programme, Institute for Security Studies

SANDF Control of the Northern and Eastern Border Areas of South Africa Ettienne Hennop, Arms Management Programme, Institute for Security Studies Occasional Paper No 52 - August 2001 INTRODUCTION Borderline control and security were historically the responsibility of the South African Police (SAP) until the withdrawal of the counterinsurgency units at the end of 1990. The Army has maintained a presence on the borders in significant numbers since the 1970s. In the Interim Constitution of 1993, borderline functions were again allocated to the South African Police Service (SAPS). However, with the sharp rise in crime in the country and the subsequent extra burden this placed on the police, the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) was placed in service by the president to assist and support the SAPS with crime prevention, including assistance in borderline security. As a result, the SANDF had a strong presence with 28 infantry companies and five aircraft deployed on the international borders of South Africa at the time.1 An agreement was signed on 10 June 1998 between the SANDF and the SAPS that designated the responsibility for borderline protection to the SANDF. In terms of this agreement, as contained in a cabinet memorandum, the SANDF has formally been requested to patrol the borders of South Africa. This is to ensure that the integrity of borders is maintained by preventing the unfettered movement of people and goods across the South African borderline between border posts. The role of the SANDF has been defined technically as one of support to the SAPS and other departments to combat crime as requested.2 In practice, however, the SANDF patrols without the direct support of the other departments. -

Phase 1 AIA / HIA Sabie Hydro Project, Hazyview

SPECIALIST REPORT PHASE 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL / HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR PROPOSED SABIE HYDRO POWER (PTY Ltd) PROJECT, ON PORTION 17 OF THE FARM TEVREDE 178 JT, HAZYVIEW, MPUMALANGA PROVINCE REPORT COMPILED FOR RHENGU ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES MR. RALF KALWA P.O. Box 1046, MALELANE, 1320 Cell: 0824147088 / Fax: 0866858003 / e-mail: [email protected] SEPTEMBER 2016 ADANSONIA HERITAGE CONSULTANTS ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHERN AFRICAN PROFESSIONAL ARCHAEOLOGISTS C. VAN WYK ROWE E-MAIL: [email protected] Tel: 0828719553 / Fax: 0867151639 P.O. BOX 75, PILGRIM'S REST, 1290 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A Phase 1 Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA) regarding archaeological and other cultural heritage resources was conducted on the footprint for the proposed Sabie Hydro Power project next to the Sabie River near Hazyview. The study area is located on portion 17 of the farm TEVREDE 178JT, Hazyview. The farm is situated on topographical maps, 1:50 000, 2530 BB (SABIE) & 2531 AA (KIEPERSOL), which is in the Mpumalanga Province. The study area is situated on 2530 BB SABIE. This area falls under the jurisdiction of the Ehlanzeni District Municipality, and Thaba Chweu Local Municipality. The National Heritage Resources Act, no 25 (1999)(NHRA), protects all heritage resources, which are classified as national estate. The NHRA stipulates that any person who intends to undertake a development, is subjected to the provisions of the Act. The applicants (private landowner with some shareholders) in co-operation with Rhengu Environmental Services are requesting the establishment of a hydro facility on the Sabie River near Hazyview. There was a hydro facility on the farm approximately 40 years ago and the new one will follow more or less the same route and alignment. -

Seasonal Metal Speciation in the Sabie River Catchment, Mpumalanga, South Africa

18th JOHANNESBURG Int'l Conference on Science, Engineering, Technology & Waste Management (SETWM-20) Nov. 16-17, 2020 Johannesburg (SA) Seasonal Metal Speciation in the Sabie River Catchment, Mpumalanga, South Africa 1,2R. Lusunzi, 1E. Fosso-Kankeu, 1F. Waanders of water. Abstract - The present study investigated the hydrochemical Various anthropogenic sources which include mining, characteristic changes of the Sabie River catchment. Water sampling agricultural activities and industrial wastewater contribute to was done in November and December (wet season, 2019) and July pollution of surface water [1], [2]. Various factors that influence (Dry season, 2020). Physicochemical parameters and metal speciation were analyzed to assess their impact on water quality and fitness for the mobility of the likely or definite contaminants from human consumption. The hydrochemical characteristics of Sabie anthropogenic activities such as mining and mineral processing catchment showed variation of quality with seasons when compared activities had been described [3] and [4]. These factors include with drinking water guidelines. Seepage from Nestor tailings storage occurrence, abundance, reactivity and hydrology. The term facility (TSF) was also collected during wet season. In both season, species had been defined as different forms of a particular aqueous metal speciation was done using the PHREEQC geochemical 2+ 2- element or its compounds [5]. For this study, the term speciation modelling code. Higher concentrations of Ca and SO4 were found in mine water while the dominant anion and cation were Mg2+ and Cl- had been used to indicate the distribution of species in samples in surface water samples. Additionally, the seasonal variation in the from the Sabie catchment. -

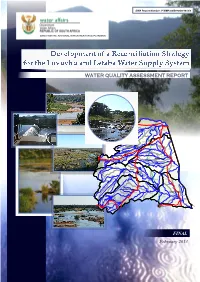

Development of a Reconciliation Strategy for the Luvuvhu and Letaba Water Supply System WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT

DWA Report Number: P WMA 02/B810/00/1412/8 DIRECTORATE: NATIONAL WATER RESOURCE PLANNING Development of a Reconciliation Strategy for the Luvuvhu and Letaba Water Supply System WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT u Luvuvh A91K A92C A91J le ta Mu A92B A91H B90A hu uv v u A92A Luvuvhu / Mutale L Fundudzi Mphongolo B90E A91G B90B Vondo Thohoyandou Nandoni A91E A91F B90C B90D A91A A91D Shingwedzi Makhado Shing Albasini Luv we uv dz A91C hu i Kruger B90F B90G A91B KleinLeta B90H ba B82F Nsami National Klein Letaba B82H Middle Letaba Giyani B82E Klein L B82G e Park B82D ta ba B82J B83B Lornadawn B81G a B81H b ta e L le d id B82C M B83C B82B B82A Groot Letaba etaba ot L Gro B81F Lower Letaba B81J Letaba B83D B83A Tzaneen B81E Magoebaskloof Tzaneen a B81B B81C Groot Letab B81A B83E Ebenezer Phalaborwa B81D FINAL February 2013 DEVELOPMENT OF A RECONCILIATION STRATEGY FOR THE LUVUVHU AND LETABA WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT REFERENCE This report is to be referred to in bibliographies as: Department of Water Affairs, South Africa, 2012. DEVELOPMENT OF A RECONCILIATION STRATEGY FOR THE LUVUVHU AND LETABA WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM: WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT Prepared by: Golder Associates Africa Report No. P WMA 02/B810/00/1412/8 Water Quality Assessment Development of a Reconciliation Strategy for the Luvuvhu and Letaba Water Supply System Report DEVELOPMENT OF A RECONCILIATION STRATEGY FOR THE LUVUVHU AND LETABA WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM Water Quality Assessment EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Department of Water Affairs (DWA) has identified the need for the Reconciliation Study for the Luvuvhu-Letaba WMA. -

Kruger National Park River Research: a History of Conservation and the ‘Reserve’ Legislation in South Africa (1988-2000)

Kruger National Park river research: A history of conservation and the ‘reserve’ legislation in South Africa (1988-2000) L. van Vuuren 23348674 Dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Magister Artium in History at the School of Basic Sciences, Vaal Triangle campus of the North-West University Supervisor: Prof J.W.N. Tempelhoff May 2017 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation is my own, unaided work. It is being submitted for the degree of Masters of Arts in the subject group History, School of Basic Sciences, Vaal Triangle Faculty, North-West University. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination in any other university. L. van Vuuren May 2017 i ABSTRACT Like arteries in a human body, rivers not only transport water and life-giving nutrients to the landscape they feed, they are also shaped and characterised by the catchments which they drain.1 The river habitat and resultant biodiversity is a result of several physical (or abiotic) processes, of which flow is considered the most important. Flows of various quantities and quality are required to flush away sediments, transport nutrients, and kick- start life processes in the freshwater ecosystem. South Africa’s river systems are characterised by particularly variable flow regimes – a result of the country’s fluctuating climate regime, which varies considerably between wet and dry seasons. When these flows are disrupted or diminished through, for example, direct water abstraction or the construction of a weir or dam, it can have severe consequences on the ecological process which depend on these flows. -

Bushbuckridge Mpumalanga Nodal Economic Profiling Project Business Trust & Dplg, 2007 Bushbuckridge Context

Nodal Economic Profiling Project Bushbuckridge Mpumalanga Nodal Economic Profiling Project Business Trust & dplg, 2007 Bushbuckridge Context IInn 22000011,, SSttaattee PPrreessiiddeenntt TThhaabboo MMbbeekkii aannnnoouunncceedd aann iinniittiiaattiivvee ttoo aaddddrreessss uunnddeerrddeevveellooppmmeenntt iinn tthhee mmoosstt sseevveerreellyy iimmppoovveerriisshheedd rruurraall aanndd uurrbbaann aarreeaass ((““ppoovveerrttyy nnooddeess””)) iinn SSoouutthh AAffrriiccaa,, wwhhiicchh hhoouussee aarroouunndd tteenn mmiilllliioonn ppeeooppllee.. TThhee UUrrbbaann RReenneewwaall PPrrooggrraammmmee ((uurrpp)) aanndd tthhee IInntteeggrraatteedd SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee RRuurraall Maruleng DDeevveellooppmmeenntt PPrrooggrraammmmee (isrdp) were created in 2001 to Sekhukhune (isrdp) were created in 2001 to aaddddrreessss ddeevveellooppmmeenntt iinn tthheessee Bushbuckridge aarreeaass.. TThheessee iinniittiiaattiivveess aarree Alexandra hhoouusseedd iinn tthhee DDeeppaarrttmmeenntt ooff Kgalagadi Umkhanyakude PPrroovviinncciiaall aanndd LLooccaall GGoovveerrnnmmeenntt ((ddppllgg)).. Zululand Maluti-a-Phofung Umzinyathi Galeshewe Umzimkhulu I-N-K Alfred Nzo Ukhahlamba Ugu Central Karoo OR Tambo Chris Hani Mitchell’s Plain Mdantsane Khayelitsha Motherwell UUP-WRD-Bushbuckridge Profile-301106-IS 2 Nodal Economic Profiling Project Business Trust & dplg, 2007 Bushbuckridge Bushbuckridge poverty node Activities z Research process Documents People z Overview z Economy – Overview – Selected sector: Tourism – Selected sector: Agriculture z Investment opportunities -

RDUCROT Baseline Report Limpopo Mozambique

LAND AND WATER GOVERNANCE AND PROPOOR MECHANISMS IN THE MOZAMBICAN PART OF THE LIMPOPO BASIN: BASELINE STUDY WORKING DOCUMENT DECEMBER 2011 Raphaëlle Ducrot Project : CPWF Limpopo Basin : Water Gouvernance 1 SOMMAIRE 1 THE FORMAL INSTITUTIONAL GOVERNANCE FRAMEWORK 6 1.1 Territorial and administrative governance 6 1.1.1 Provincial level 6 1.1.2 District level 7 1.1.3 The Limpopo National Park 9 1.2 Land management 11 1.3 Traditional authorities 13 1.4 Water Governance framework 15 1.4.1 International Water Governance 15 1.4.2 Governance of Water Resources 17 a) Water management at national level 17 b) Local and decentralized water institutions 19 ARA 19 The Limpopo Basin Committee 20 Irrigated schemes 22 Water Users Association in Chokwé perimeter (WUA) 24 1.4.3 Governance of domestic water supply 25 a) Cities and peri-urban areas (Butterworth and O’Leary, 2009) 25 b) Rural areas 26 1.4.4 Local water institutions 28 1.4.5 Governance of risks and climate change 28 1.5 Official aid assistance and water 29 1.6 Coordination mechanisms 30 c) Planning and budgeting mechanisms in the water sector (Uandela, 2010) 30 d) Between government administration 31 e) Between donor and government 31 f) What coordination at decentralized level? 31 2 THE HYDROLOGICAL FUNCTIONING OF THE MOZAMBICAN PART OF THE LIMPOPO BASIN 33 2.1 Description of the basin 33 2.2 Water availability 34 2.2.1 Current uses (Van der Zaag, 2010) 34 2.2.2 Water availability 35 2.3 Water related risks in the basin 36 2.4 Other problems 36 2 3 WATER AND LIVELIHOODS IN THE LIMPOPO BASIN 37 3.1 a short historical review 37 3.2 Some relevant social and cultural aspects 40 3.3 Livelihoods in Limpopo basin 42 3.4 Gender aspects 45 3.5 Vulnerability to risks and resilience 46 3.5.1 Water hazards: one among many stressors. -

HOW to GET to SABI SABI on the Portia Shabangu Drive (Old Kruger Gate Road) the Turn-Off to Sabi Sabi Is Approximately 37Km from Hazyview

HOW TO GET TO SABI SABI On the Portia Shabangu Drive (Old Kruger Gate Road) the turn-off to Sabi Sabi is approximately 37km from Hazyview. Turn left onto a gravel road and follow the signs to Sabi Sabi. Little Bush Camp To Bushbuckridge To Shaws Gate Fill in form at gate Selati Camp Entrance fee payable Bush Lodge To Sabi Town Second sign 2km to Sabi Sabi Airstrip Traffic Sabie River Lights Earth Lodge N Signboard to R536 Hazyview Portia Shabangu Drive R536 (Old Kruger Gate Road) Kruger Gate/Hek 37km 4km Shopping Centre Traffic First sign Lights to Sabi Sabi To Sabi Town 2km 47km 19km At stop turn left IGNORE Nelspruit R40 White River road signs to Sabi Town KMIA KRUGER SABI SAND NATIONAL Sand PARK WiltUIN Bosbokrand Sabi Sabi Newington Gate Private Pilgrim’s Rest Shaws Gate Game Reserve Graskop R536 R533 Sabie Sabie Paul Kruger Gate Skukuza Airport Hazyview Sabie R516 Kiepersol R40 R37 R538 Plaston KRUGER NATIONAL White River Kruger PARK Mpumalanga Airport R538 Hectorspruit N4 Elandshoek Nelspruit N4 Malalane Gate DIRECTIONS TO SABI SABI From Johannesburg OR Tambo International Airport take the R21in the direction of Boksburg / East Rand. Then take the N12 towards Emalahleni (Witbank). This road becomes the N4 toll road to Nelspruit. Just after Machadodorp Toll the N4 splits with either option getting you to Nelspruit. Once in Nelspruit follow the signs to White River. A new bypass is available or you can continue into Nelspruit and take the R40 to White River. As you enter White River proceed on the main road and turn left at the 4th traffic light into Theo Kleynhans Street towards Hazyview.