Avoiding Slush for Hot-Point Drilling of Glacier Boreholes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the United States District Court for the District of Maine

Case 2:21-cv-00154-JDL Document 1 Filed 06/14/21 Page 1 of 13 PageID #: 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MAINE ICE CASTLES, LLC, a Utah limited liability company, Plaintiff, COMPLAINT vs. Case No.: ____________ CAMERON CLAN SNACK CO., LLC, a Maine limited liability company; HARBOR ENTERPRISES MARKETING AND JURY TRIAL DEMANDED PRODUCTION, LLC, a Maine limited liability company; and LESTER SPEAR, an individual, Defendants. Plaintiff Ice Castles, LLC (“Ice Castles”), by and through undersigned counsel of record, hereby complains against Defendants Cameron Clan Snack Co., LLC; Harbor Enterprises Marketing and Production, LLC; and Lester Spear (collectively, the “Defendants”) as follows: PARTIES 1. Ice Castles is a Utah limited liability company located at 1054 East 300 North, American Fork, Utah 84003. 2. Upon information and belief, Defendant Cameron Clan Snack Co., LLC is a Maine limited liability company with its principal place of business at 798 Wiscasset Road, Boothbay, Maine 04537. 3. Upon information and belief, Defendant Harbor Enterprises Marketing and Production, LLC is a Maine limited liability company with its principal place of business at 13 Trillium Loop, Wyman, Maine 04982. Case 2:21-cv-00154-JDL Document 1 Filed 06/14/21 Page 2 of 13 PageID #: 2 4. Upon information and belief, Defendant Lester Spear is an individual that resides in Boothbay, Maine. JURISDICTION AND VENUE 5. This is a civil action for patent infringement arising under the Patent Act, 35 U.S.C. § 101 et seq. 6. This Court has subject matter jurisdiction over this controversy pursuant to 28 U.S.C. -

A Hail Size Distribution Impact Transducer

A Hail Size Distribution Impact Transducer John E. Lanea, Robert C. Youngquistb, William D. Haskella, and Robert B. Coxa aASRC Aerospace Corporation, P.O. Box 21087, Kennedy Space Center, FL 32815 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] bNational Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Kennedy Space Center, FL 32899 [email protected] Abstract: An active impact transducer has been designed and tested for the purpose of monitor- ing hail fall in the vicinity of the Space Shuttle launch pads. An important outcome of this design is the opportunity to utilize frequency analysis to discriminate between the audio signal generat- ed from raindrop impacts and that of hailstone impacts. The sound of hail impacting a metal plate is subtly but distinctly different than the sound of rain impacts. This useful characteristic permits application of signal processing algorithms that are inherently more robust than tech- niques relying on amplitude processing alone in the implementation of a hail disdrometer. 1 1. Introduction Impact disdrometers have long been a useful meteorological tool to measure and quantify rainfall drop size distributions, where a drop momentum is converted into a single electrical im- pulse.1,2 The electrical impulse amplitude is converted to an estimate of drop diameter by means of an empirical calibration formula. The calibration may be a one-time procedure involving dropping numerous known-size-calibration drops from a tower of sufficient height to achieve terminal velocity. The test drop sizes must adequately span the size range of interest. Alternative- ly, or as a supplement to the single drop calibration, an in situ method of comparing the sum of accumulated drop impulses to the tip time interval of a tipping-bucket rain gauge may be uti- lized.3 Prior to launch, the Space Shuttle and other NASA launch vehicles are primarily large ther- mos bottles containing substantial quantities of cryogenic fuels. -

ICE COVERED LAKES Ice Formation Thermal Regime

I ICE COVERED LAKES Ice formed from the underside of the ice sheet has crys- tals with columnar structure; it is possible to see through the ice. Such ice is called black ice. Ice can also be formed Lars Bengtsson in a slush layer between the snow and the top of the ice. Department of Water Resources Engineering, When the weight of the snow is more than the lifting force Lund University, Lund, Sweden from the ice, the ice cover is forced under the water surface and water enters into the snow which becomes saturated Ice formation with water. When this slush layer freezes, snow ice or Lakes at high latitudes or high altitudes are ice covered white ice is formed. The crystals in this kind of ice are ran- part of the year; typically from November to April and in domly distributed. This ice is not transparent but looks the very north sometimes from October to early June. Arc- somewhat like milk. An example of ice growth is shown tic lakes may be ice covered throughout the year. When in Figure 1 from a bay in the Luleå archipelago (almost there is a regular ice cover for several months, the ice fresh water). thickness reaches more than ½ meter. At mid latitudes The ice on a lake has ecological consequences. Since occasional ice cover may appear for short periods several there is no exchange with the atmosphere, the oxygen con- times during a winter. Where there is a stable ice cover, tent of the water decreases and the bottom layers may be ice roads are prepared. -

Guidelines for Safe Ice Construction

GUIDELINES FOR SAFE ICE CONSTRUCTION 2015 GUIDELINES FOR SAFE ICE CONSTRUCTION Department of Transportation February 2015 This document is produced by the Department of Transportation of the Government of the Northwest Territories. It is published in booklet form to provide a comprehensive and easy to carry reference for field staff involved in the construction and maintenance of winter roads, ice roads, and ice bridges. The bearing capacity guidance contained within is not appropriate to be used for stationary loads on ice covers (e.g. drill pads, semi-permanent structures). The Department of Transportation would like to acknowledge NOR-EX Ice Engineering Inc. for their assistance in preparing this guide. Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................5 2.0 DEFINITIONS ....................................................8 3.0 ICE BEHAVIOR UNDER LOADING ................................13 4.0 HAZARDS AND HAZARD CONTROLS ............................17 5.0 DETERMINING SAFE ICE BEARING CAPACITY .................... 28 6.0 ICE COVER MANAGEMENT ..................................... 35 7.0 END OF SEASON GUIDELINES. 41 Appendices Appendix A Gold’s Formula A=4 Load Charts Appendix B Gold’s Formula A=5 Load Charts Appendix C Gold’s Formula A=6 Load Charts The following Appendices can be found online at www.dot.gov.nt.ca Appendix D Safety Act Excerpt Appendix E Guidelines for Working in a Cold Environment Appendix F Worker Safety Guidelines Appendix G Training Guidelines Appendix H Safe Work Procedure – Initial Ice Measurements Appendix I Safe Work Procedure – Initial Snow Clearing Appendix J Ice Cover Inspection Form Appendix K Accident Reporting Appendix L Winter Road Closing Protocol (March 2014) Appendix M GPR Information Tables 1. Modification of Ice Loading and Remedial Action for various types of cracks .........................................................17 2. -

Best Practices for Building and Working Safely on Ice Covers in Ontario

Best Practices for Building and Working Safely on Ice Covers in Ontario ihsa.ca IHSA has additional information on this and other topics. Visit ihsa.ca or call Customer Service at 1-800-263-5024 The contents of this publication are for general information only. This publication should not be regarded or relied upon as a definitive guide to government regulations or to safety practices and procedures. The contents of this publication were, to the best of our knowledge, current at the time of printing. However, no representations of any kind are made with regard to the accuracy, completeness, or sufficiency of the contents. The appropriate regulations and statutes should be consulted. In case of any inconsistency between this document and the Occupational Health and Safety Act or associated regulations, the legislation will always prevail. Readers should not act on the information contained herein without seeking specific independent legal advice on their specific circumstance. The Infrastructure Health & Safety Association is pleased to answer individual requests for counselling and advice. The basis for this document is the 2013 version of the Government of Alberta’s Best Practices for Building and Working Safely on Ice Covers in Alberta. The content has been used with permission from the Government of Alberta. This document is dedicated to the nearly 500 people in Canada who have lost their lives over the past 10 years while crossing or working on floating ice. Over the period of 1991 to 2000, there were 447 deaths associated with activities on ice. Of these, 246 involved snowmobiles, 150 involved non-motorized activity, and 51 involved motorized vehicles. -

East Antarctic Sea Ice in Spring: Spectral Albedo of Snow, Nilas, Frost Flowers and Slush, and Light-Absorbing Impurities in Snow

Annals of Glaciology 56(69) 2015 doi: 10.3189/2015AoG69A574 53 East Antarctic sea ice in spring: spectral albedo of snow, nilas, frost flowers and slush, and light-absorbing impurities in snow Maria C. ZATKO, Stephen G. WARREN Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Spectral albedos of open water, nilas, nilas with frost flowers, slush, and first-year ice with both thin and thick snow cover were measured in the East Antarctic sea-ice zone during the Sea Ice Physics and Ecosystems eXperiment II (SIPEX II) from September to November 2012, near 658 S, 1208 E. Albedo was measured across the ultraviolet (UV), visible and near-infrared (nIR) wavelengths, augmenting a dataset from prior Antarctic expeditions with spectral coverage extended to longer wavelengths, and with measurement of slush and frost flowers, which had not been encountered on the prior expeditions. At visible and UV wavelengths, the albedo depends on the thickness of snow or ice; in the nIR the albedo is determined by the specific surface area. The growth of frost flowers causes the nilas albedo to increase by 0.2±0.3 in the UV and visible wavelengths. The spectral albedos are integrated over wavelength to obtain broadband albedos for wavelength bands commonly used in climate models. The albedo spectrum for deep snow on first-year sea ice shows no evidence of light- absorbing particulate impurities (LAI), such as black carbon (BC) or organics, which is consistent with the extremely small quantities of LAI found by filtering snow meltwater. -

Global Reporting Format AIS Aspects (SNOWTAM)

Global Reporting Format AIS Aspects (SNOWTAM) Christopher KEOHAN on behalf of Abbas NIKNEJAD Regional Officer, Air Navigation Systems Implementation ICAO EUR/NAT Office ICAO EUR GRF Implementation Workshop (Frankfurt, Germany, 10-11 December 2019) What is GRF? • A globally-harmonized methodology for runway surface conditions assessment and reporting to provide reports that are directly related to the performance of aeroplanes. Aeronautical information Aircraft operators utilize the services (AIS) provide the Aerodrome operator assess the information in conjunction with information received in the RCR runway surface conditions, the performance data provided to end users (SNOWTAM) including contaminants, for by the aircraft manufacturer to each third of the runway determine if landing or take-off length, and report it by mean of operations can be conducted a uniform runway condition Air traffic services (ATS) provide safely and provide runway report (RCR) the information received via the braking action special air-report RCR to end users (radio, ATIS) (AIREP) and received special air-reports 2 Dissemination of information • Through the AIS and ATS services: when the runway is wholly or partly contaminated by standing water, snow, slush, ice or frost, or is wet associated with the clearing or treatment of snow, slush, ice or frost. • Through the ATS only: when the runway is wet, not associated with the presence of standing water, snow, slush, ice or frost. AIS • SNOWTAM • Voice ATS • ATIS 3 Amendment 39B to Annex 15 Amendment 39B arises from: • Recommendations of the Friction Task Force of the Aerodrome Design and Operations Panel (ADOP) relating to the use of a global reporting format for assessing and reporting runway surface conditions. -

Icebergs Lesson by Pat Williams, Eugene, OR

TEACHER BACKGROUND Unit 1 - The Ocean Icebergs Lesson by Pat Williams, Eugene, OR Key Concepts 1. Large quantities of water on the earth exist as a solid in the form of ice and snow, including glaciers and icebergs. 2. Water is unique among liquids in that it becomes less dense as it turns to solid ice, a fact which allows ice to float on liquid water. 3. Water can change from a solid (ice) to a liquid. 4. Ice melts faster when broken into little pieces. Background Sea Ice and Icebergs When we think of the world ocean, often we picture rolling waves as far as the eye can see. While this is an accurate picture, it is not the only one. At the poles, vast reaches of the ocean are covered by ice. As winter approaches the north or south pole, air temperatures fall so low that seawater begins to freeze, forming a layer of slush. The slush congeals into sheets of new sea ice. In turn, these sheets of ice are broken into “pancakes” by waves and wind. As freezing continues the pancakes unite to form larger masses called floes. Some ice floes move with the currents and wind, shifting constantly. Others remain anchored to land. Other ice also floats in the sea. In both the northern and southern polar regions, giant masses of ice, called icebergs, break away from glaciers. Icebergs produced in the Arctic drift south as far as New England and into the busy shipping lanes of the North Atlantic. It was one of these icebergs that caused the infamous sinking of the Titanic on its maiden voyage in 1912, killing 1,517 people. -

Contaminated and Slippery Runways

CONTAMINATED AND SLIPPERY RUNWAYS Contaminated and Slippery Runways Cont Rwy.2 CONTAMINATED AND SLIPPERY RUNWAYS Agenda: • Basic Regulations and Definitions • Physics of Contaminated Runways • Operational Practice • Operational Data/Applications • Other Considerations Cont Rwy.3 CONTAMINATED AND SLIPPERY RUNWAYS Contaminated runway – More than 25% of the runway is covered by slush, standing water, snow covered, Ice covered or compacted snow Cont Rwy.4 CONTAMINATED AND SLIPPERY RUNWAYS Regulatory Requirements • FAA Operators Historically No definitive regulatory requirements for contaminated or slippery runway performance adjustments in Part 25 or 121 Current (737-6/7/8/900) - Wet runway is part of AFM certification basis No definitive regulatory requirements for contaminated or slippery (non-wet) Cont Rwy.5 CONTAMINATED AND SLIPPERY RUNWAYS Regulatory Requirements • FAA Guidelines: – Current approved guidelines published in Advisory Circular 91-6A, May 24, 1978 – Provides guidelines for operation with standing water, slush, snow or ice on runway – Does not provide for wet runways – Proposed Advisory Circular 91-6B (draft) Cont Rwy.6 CONTAMINATED AND SLIPPERY RUNWAYS Regulatory Requirements • JAA Operators - New certifications – Specific requirements covered in the AFM – Includes performance based on various runway conditions (wet, compact snow, wet ice, slush, dry snow) • JAROPS 1 – Requires operational contaminated/slippery runway data based on possibility of an engine failure Cont Rwy.7 CONTAMINATED AND SLIPPERY RUNWAYS Proposed Advisory -

Slush Machine Uss-Smm00001

SLUSH MACHINE USS-SMM00001 This manual should be made available to all users of this equipment. For best results, and for maximum durability of the equipment, carefully read and follow all instructions. Failure to do so can lead to serious injury or catastrophic damage to the user, machine, supplies, or surrounding areas. All safety suggestions must be followed closely, and extreme precaution must be taken to assure proper use of the equipment by only qualified personnel who have read this guide. Table of Contents I. Introduction.....................................................................................................................................1 II. Safety Notes.....................................................................................................................................2 III. Parameters.......................................................................................................................................3 IV. Setting Up the Machine..............................................................................................................4 V. Operating the Machine...............................................................................................................4 VI. Making your Slush.........................................................................................................................6 VII.Troubleshooting............................................................................................................................6 VIII. Cleaning the Machine...............................................................................................................8 -

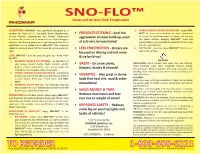

SNO-FLO™ Snow and Ice Anti-Stick Encapsulant

SNO-FLO™ Snow and Ice Anti-Stick Encapsulant DESCRIPTION: SNO-FLO™ was specifically designed as a 2. DURING WINTER STORM OPERATIONS - Apply SNO- solution for State DOT’s, Municipal Street Departments, • PREVENTS STICKING - And the FLO™ to snow accumulations on your equipment County Highway Departments and Private Contractors aggravation of snow build-up, even to break the bond between the snow and ice and to reduce the frustration of snow and ice slush sticking to the metal surface. Reapply SNO-FLO™ once the vehicles and de-icing equipment used during winter storm at sub-zero temperatures! accumulations are removed to prevent further snow operations. As an added bonus SNO-FLO™ also improves and ice slush build-up. safety by reducing snow fog from covering up your warning • LESS FRUSTRATION - Drivers are 3. ON THE GO - you may apply SNO-FLO™ directly to a lights. focused on driving and not snow wet or dry surface. USES: SNO-FLO™ can be used to give you three main benefits: & ice build-up! 1. PREVENTS SNOW & ICE STICKING - on the faces of WARNING your plows, blower chutes, loader buckets, grader • GREAT - On snow plows, PRECAUTION: Avoid contact with eyes, skin and clothing. blades, vehicle dump beds, and even prevents the Avoid breathing mists. Wear protective clothing, gloves, blowers, blades & shovels! eye protection. Wash thoroughly with soap and water after formation of snow pack under wheel-wells. handling. Keep containers closed when not in use. Keep out of 2. GREATLY REDUCES SHOVELING FATIGUE - shoveling is reach of children. a heavy job without the added weight of snow sticking • VERSATILE - Also great in dump RESPONSE: to your shovel. -

The Detection of Black Ice Accidents for Preventative Automated Vehicles Using Convolutional Neural Networks

electronics Article The Detection of Black Ice Accidents for Preventative Automated Vehicles Using Convolutional Neural Networks Hojun Lee 1, Minhee Kang 2 , Jaein Song 3 and Keeyeon Hwang 1,* 1 Department of Urban Design & Planning, Hongik University, Seoul 04066, Korea; [email protected] 2 Department of Smartcity, Hongik University Graduate School, Seoul 04066, Korea; [email protected] 3 Research Institute of Science and Technology, Hongik University, Seoul 04066, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-010-8654-7415 Received: 13 November 2020; Accepted: 16 December 2020; Published: 18 December 2020 Abstract: Automated Vehicles (AVs) are expected to dramatically reduce traffic accidents that have occurred when using human driving vehicles (HVs). However, despite the rapid development of AVs, accidents involving AVs can occur even in ideal situations. Therefore, in order to enhance their safety, “preventive design” for accidents is continuously required. Accordingly, the “preventive design” that prevents accidents in advance is continuously required to enhance the safety of AVs. Specially, black ice with characteristics that are difficult to identify with the naked eye—the main cause of major accidents in winter vehicles—is expected to cause serious injuries in the era of AVs, and measures are needed to prevent them. Therefore, this study presents a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)-based black ice detection plan to prevent traffic accidents of AVs caused by black ice. Due to the characteristic of black ice that is formed only in a certain environment, we augmented image data and learned road environment images. Tests showed that the proposed CNN model detected black ice with 96% accuracy and reproducibility.