The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 14 (Summer 2015)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BFMS Newsletter 2004-12.Indd

BALTIMORE FOLK MUSIC SOCIETY Member, Country Dance & Song Society www.bfms.org December 2004 Somebody Scream Productions Sponsored by BFMS and CCBC/CC Offi ce of Student Events presents Dikki Du and the Zydeco Crew Dikki Du returns to Catonsville with his Zydeco Crew of family and friends to provide rhythmic, hard driving music for your dancing pleasure. It should be known that Dikki (aka Troy) is the son of Roy Carrier, brother to Chubby Carrier and cousin to Dwight Carrier. Needless to say talent runs in the family! He impressed at Buff alo Jambalaya this year as he backed two bands on drums and also showed us his love of accordion. Admission: $12/$10 BFMS members/$5 CCBC/CC students with ID. Free, well-lit parking is available. Directions: From I-95, take exit 47 (Route 195). Follow signs for Route 166. Turn right onto Route 166 North (Rolling Road) towards Catonsville. At the second traffi c light (Valley Road), turn left into Catonsville Community College campus. Th e Barn Th eater is the stone building on the hill beyond parking lot A. Info: [email protected], www.WhereWeGoTo- Zydeco.com Th e Barn Th eater Catonsville Community College, Catonsville Saturday, Dec. 4, Dance lesson: 8 pm Music: 9 pm–midnight BFMS American Contra and Square Dance Dec. 1 Dec. 29 Sue Dupre with Sugar Beat: Susan Brandt (fl ute), Marc Glick- Open Band Night with caller Bob Hofkin. man (piano), and Elke Baker (fi ddle). Lovely Lane Church Dec. 8 2200 St. Paul St., Baltimore Steve Gester with the Altered Gardeners: Dave Weisler (piano, guitar), Alexander Mitchell (fi ddle), and George Paul (piano, Wednesday evenings, 8–11 pm accordion). -

The Vulnerabilities of Developed States to Economic Cyber Warfare

Working Paper The Vulnerabilities of Developed States to Economic Cyber Warfare Paul Cornish Head, International Security Programme and Carrington Professor of International Security, Chatham House June 2011 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication. Working Paper: The Vulnerabilities of Developed States to Economic Cyber Warfare INTRODUCTION The central features of the ‘cybered’ world of the early 21st century are the interconnectedness of global communications, information and economic infrastructures and the dependence upon those infrastructures in order to govern, to do business or simply to live. There are a number of observations to be made of this world. First, it is still evolving. Economically developed societies are becoming ever more closely connected within themselves and with other, technologically advanced societies, and all are becoming increasingly dependent upon the rapid and reliable transmission of ideas, information and data. Second, where interconnectedness and dependency are not managed and mitigated by some form of security procedure, reversionary mode or redundancy system, then the result can only be a complex and vitally important communications system which is nevertheless vulnerable to information theft, financial electronic crime, malicious attack or infrastructure breakdown. -

Boskone 31 a Convention Report by Evelyn C

Boskone 31 A convention report by Evelyn C. Leeper Copyright 1994 by Evelyn C. Leeper Table of Contents: l Hotel l Dealers Room l Art Show l Programming l The First Night l Comic Books and Alternate History l Sources of Fear in Horror l Saturday Morning l Immoral Fiction? l Neglected SF and Fantasy Films l Turbulence and Psychohistory l Creating an Internally Consistent Religion l Autographing l Parties l Origami l The Forgotten Fantasists: Swann, Warner, and others l The City and The Story l What's BIG in the Small Press l The Transcendent Man--A Theme in SF and Fantasy l Does It Have to Be a SpaceMAN?: Gender and Characterization l Deconstructing Tokyo: Godzilla as Metaphor, etc. l The Green Room l Leaving l Miscellaneous l Appendix: Neglected Fantasy and Science Fiction Films Last year the drive was one hour longer due to the move from Springfield to Framingham, and three hours longer coming back, because there was a snowstorm added on as well. This year it was another hour longer going up because of wretched traffic, but only a half-hour longer coming back. (Going up we averaged 45 miles per hour, but never actually went 45 miles per hour--it was either 10 miles per hour or 70 miles per hour, and when it was 10, the heater was going full blast because the engine was over-heating.) Having everything in one hotel is nice, but is it worth it? Three years ago, panelists registered in the regular registration area and were given their panelist information there. -

Exhibition Details

2 3 A WARM WELCOME TO OUR ANNUAL PHOTOGRAPHY EXHIBITION I would like to extend a very warm welcome to our photographic exhibition. It seems to come round quicker each year or is that I am getting older! A big thanks goes to the Exhibition Committee, and Jean in particular, for organising this event which involves a lot of work. Thanks also to the members who have helped in various ways, in- cluding putting the displays up, and who will be helping with teas and other duties over the dura- tion of the exhibition. Thank you also to the Judge Nat Coalson ARPS for giving his time to judge an increased number of both print and PDI entries, the whole process taking the best part of a day. We are back at Christchurch again this year because it is an excellent venue for our exhibition with plenty of space and lots of light. Don’t forget the teas and coffees that are available through- out Friday night and all day Saturday. There are also delicious cakes on sale, some homemade. So please try them. Our friendly volunteers will be waiting to serve you. We are displaying images from other clubs as well as our own. As well as the print display there are also projected digital images (PDI) to be enjoyed while you have a drink. I hope that you will agree with the judge on the high quality of all the images displayed. Finally, if you like what you see. perhaps you may consider attending one of our meetings when we meet again in September. -

Magazine Media

FEBRUARY 2010: THE FANTASY ISSUE M M MediaMagazine edia agazine Menglish and media centre issue 31 | februaryM 2010 Superheroes Dexter Vampires english and media centre Aliens Dystopia Apocalypses | issue 31 | february 2010 MM MM MediaMagazine is published by the English and Media Centre, a non-profit making organisation. editorial The Centre publishes a wide range of classroom materials and runs courses for teachers. If you’re studying English at A Level, look out e thought our last issue, on Reality, was one of our best yet, for emagazine, also published by Wbut this Fantasy-themed edition is just as inspired. Perhaps the Centre. our curiosity about the real and our fascination with fantasy are two sides of the same coin … The English and Media Centre 18 Compton Terrace By way of context, Annette Hill explores the factors behind London N1 2UN our current passion for the afterlife and the paranormal, while Telephone: 020 7359 8080 Chris Bruce suggests ways of investigating fantasy across media Fax: 020 7354 0133 platforms from an examiner’s perspective and Jerome Monahan provides an Email for subscription enquiries: illustrated history of fantasy at the movies via Jung, the Gothic and the ghost story. [email protected] We have a volley of vampires from Buffy to True Blood’s Bill, by way of Let The Right One In, and some persuasive and chilling accounts of how they represent real world Managing Editor: Michael Simons prejudices and fears. In a cluster of superhero articles, Matt Freeman explores the Editor: Jenny Grahame cultural significance of Superman, while Steph Hendry unpicks the ideologies of Editorial assistant/admin: superheroes and their relevance in a post-9/11 world – and identifies the world’s Rebecca Scambler first superheroic serial-killer. -

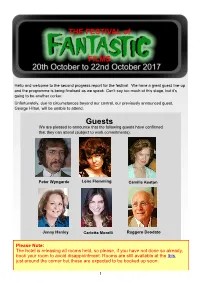

Guests We Are Pleased to Announce That the Following Guests Have Confirmed That They Can Attend (Subject to Work Commitments)

Hello and welcome to the second progress report for the festival. We have a great guest line-up and the programme is being finalised as we speak. Can’t say too much at this stage, but it’s going to be another corker. Unfortunately, due to circumstances beyond our control, our previously announced guest, George Hilton, will be unable to attend. Guests We are pleased to announce that the following guests have confirmed that they can attend (subject to work commitments). Peter Wyngarde Lone Flemming Camille Keaton Jenny Hanley Carlotta Morelli Ruggero Deodato Please Note: The hotel is releasing all rooms held, so please, if you have not done so already, book your room to avoid disappointment. Rooms are still available at the Ibis, just around the corner but these are expected to be booked up soon. 1 Welcome to the Festival : Once again the Festival approaches and as always it is great looking forward to meeting old friends again and talking films. The main topic of conversation so far this year seems to be the imminent arrival of some more classic Hammer films on Blu Ray, at long last. Like so many of you, I am very much looking forward to these and it is fortuitous that this year Jenny Hanley is making a return visit to our festival, just as her Hammer magnum opus with Christopher Lee and Dennis Waterman, Scars of Dracula is on the list of new blu rays being released. I am having to face the inevitable question of how much longer I can go on, but that is not your problem. -

INNOVATION Under Austerity

Issue 68, 1st Quarter 2013 INNOVATION Under Austerity European Missile Defense Military Values JOINT FORCE QUARTERLY Inside Issue 68, 1st Quarter 2013 Editor Col William T. Eliason, USAF (Ret.), Ph.D. JFQ Dialogue Executive Editor Jeffrey D. Smotherman, Ph.D. Supervisory Editor George C. Maerz Letters 2 Production Supervisor Martin J. Peters, Jr. From the Chairman Senior Copy Editor Calvin B. Kelley 4 Copy Editor/Office Manager John J. Church, D.M.A Bridging the Basics By Bryan B. Battaglia 6 Internet Publications Editor Joanna E. Seich Director, NDU Press Frank G. Hoffman Forum Design Chris Dunham, Guy Tom, and Jessica Reynolds U.S. Government Printing Office Executive Summary 8 Printed in St. Louis, Missouri by 10 Russia and European Missile Defenses: Reflexive Reset? By Stephen J. Cimbala Military Wisdom and Nuclear Weapons By Ward Wilson 18 NDU Press is the National Defense University’s Managing Foreign Assistance in a CBRN Emergency: The U.S. Government cross-component, professional military and 25 academic publishing house. It publishes books, Response to Japan’s “Triple Disaster” By Suzanne Basalla, William Berger, journals, policy briefs, occasional papers, and C. Spencer Abbot monographs, and special reports on national security strategy, defense policy, interagency 32 Operationalizing Mission Command: Leveraging Theory to Achieve cooperation, national military strategy, regional Capability By Kathleen Conley security affairs, and global strategic problems. Special Feature This is the official U.S. Department of Defense edition of JFQ. Any copyrighted portions of this The 600-pound Gorilla: Why We Need a Smaller Defense Department journal may not be reproduced or extracted without 36 permission of the copyright proprietors. -

2021 Honors Thesis Abstracts

ABSTRACTS OF THESIS PROJECTS SPRING 2021 The Honors Program and University Scholars ABSTRACTS OF THESIS PROJECTS SPRING 2021 Mahlet Adugna, Biology LesLee Funderburk, mentor The Effects of Leucine Supplementation on Lean Mass and Strength in Young and Midlife Adults Leucine is well known as a supplement that has the ability to augment lean mass and strength. Multiple studies on the benefits of leucine supplementation in older age groups have been published. Thus, this review focuses on examining articles studying the effects of leucine supplementation in younger and middle-aged subjects. In such studies, strength and body composition were assessed and comparisons made between those subjects taking placebo versus those taking the actual supplement. Fat mass, lean tissue mass, and maximum strength measurements are key variables used to assess the success of the supplementation as they indicate body composition changes as well as strength gains. Furthermore, the effects of leucine supplementation during periods of inactivity or bed rest were also examined. In this review, the CINHAL and Pubmed databases were used to choose a total of ten articles with young adult (18-35) and middle-aged (36-55) subjects and then analyzed on the categorical basis of gender, age group, training program length, and leucine dose. Common limitations of studies were discussed as well as implications of the use of leucine supplementation in the younger population. Mia Angeliese, Psychology Jennifer Howell, mentor “Made in the Image of God” – How the Tripartite Mind-Body-Spirit Structure of Humankind Mirrors the Trinitarian Structure of God, an Ontological Theory This thesis presents a new ontological theory of imago Dei (the image of God) in humankind. -

Armageddon and Beyond

Armageddon and Beyond by Richard F. Ames Mankind is developing newer and more frightening technologies with which to destroy itself, while political and social tensions increase around the world. Will the years just ahead of us bring worldwide nuclear devastation, or usher in an era of lasting peace? Will the prophesied “Battle of Armageddon” soon bring destruction and death to our planet? What will “Armageddon” mean to you and your loved ones? And what will come afterward? Your Bible reveals a frightening time ahead—but there is ultimate hope! Read on, to learn the amazing truth! AB Edition 1.0, December 2007 ©2007 LIVING CHURCH OF GODTM All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. This booklet is not to be sold! It has been provided as a free public educational service by the Living Church of God Scriptures in this booklet are quoted from the New King James Version (©Thomas Nelson, Inc., Publishers) unless otherwise noted. Cover: Tomorrow’s World Illustration n the first decade of the 21st century, most of us realize we live in a very dangerous world. It was just six decades ago that a I new weapon of unprecedented capacity was first unleashed, when the United States dropped atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan on August 6 and 9, 1945. A new era of mass destruction had begun. At the end of World War II, General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, accepted Japan’s uncondi- tional surrender. Aboard the battleship U.S.S. Missouri, General MacArthur summarized the danger and the choice facing humanity in this new era: “Military alliances, balances of power, leagues of nations, all in turn failed, leaving the only path to be the way of the crucible of war. -

Wild Abandon: Postwar Literature Between Ecology and Authenticity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--English English 2018 WILD ABANDON: POSTWAR LITERATURE BETWEEN ECOLOGY AND AUTHENTICITY Alexander F. Menrisky University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1241-8415 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2018.150 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Menrisky, Alexander F., "WILD ABANDON: POSTWAR LITERATURE BETWEEN ECOLOGY AND AUTHENTICITY" (2018). Theses and Dissertations--English. 66. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/english_etds/66 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the English at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--English by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Guide to the William K

Guide to the William K. Everson Collection George Amberg Memorial Film Study Center Department of Cinema Studies Tisch School of the Arts New York University Descriptive Summary Creator: Everson, William Keith Title: William K. Everson Collection Dates: 1894-1997 Historical/Biographical Note William K. Everson: Selected Bibliography I. Books by Everson Shakespeare in Hollywood. New York: US Information Service, 1957. The Western, From Silents to Cinerama. New York: Orion Press, 1962 (co-authored with George N. Fenin). The American Movie. New York: Atheneum, 1963. The Bad Guys: A Pictorial History of the Movie Villain. New York: Citadel Press, 1964. The Films of Laurel and Hardy. New York: Citadel Press, 1967. The Art of W.C. Fields. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1967. A Pictorial History of the Western Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1969. The Films of Hal Roach. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1971. The Detective in Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1972. The Western, from Silents to the Seventies. Rev. ed. New York: Grossman, 1973. (Co-authored with George N. Fenin). Classics of the Horror Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1974. Claudette Colbert. New York: Pyramid Publications, 1976. American Silent Film. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978, Love in the Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1979. More Classics of the Horror Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1986. The Hollywood Western: 90 Years of Cowboys and Indians, Train Robbers, Sheriffs and Gunslingers, and Assorted Heroes and Desperados. Secaucus, N.J.: Carol Pub. Group, 1992. Hollywood Bedlam: Classic Screwball Comedies. Secaucus, N.J.: Carol Pub. Group, 1994. -

Elijah Dating Christine

Mar 07, · Christine Sydelko and Elijah Daniel announced their professional split back in January, but insisted they were still friends. However, judging by their latest tweets, we can sense a bit of tension. Aug 29, · The two former creative partners clashed on Twitter Elijah Daniel and Christine Sydelko, former friends and partners have come head to head on Twitter. The two creators were at Author: Team Unicorns. Feb 21, · Christine started on Vine and Elijah started on Twitter, both for comedy. Now they make videos together, are engaged, and have the most electric videos on YouTube. When you hear that “bing bong,” know it’s a video from Elijah and Christine. None other than my gay best friend introduced me to the timeless renuzap.podarokideal.ru: Samantha Finley. Is elijah still dating christine - Find a man in my area! Free to join to find a woman and meet a woman online who is single and seek you. Join the leader in relations services and find a date today. Join and search! Rich woman looking for older man & younger man. I'm laid back and get along with everyone. Looking for an old soul like myself. I'm a man. Christine Sydelko is best known for being a YouTuber. Social media star who collaborates with her friend Elijah on the YouTube channel Elijah & Christine, which . Apr 28, · Elijah used his status to end her relationship with Christine Royce, so that she would follow him into the Mojave. Veronica was kept in the dark about the affair, and her reverence of Elijah only increased.