Failure to Thrive and Cognitive Development in Toddlers with Infantile Anorexia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHALLENGING CASES: BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL PEDIATRICS Failure to Thrive in a 4-Month-Old Nursing Infant

CHALLENGING CASES: BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL PEDIATRICS Failure to Thrive in a 4-Month-Old Nursing Infant* CASE visits she was observed to respond quickly to visual Christine, a 4-month-old infant, is brought to the and auditory cues. There was no family history of office for a health-supervision visit by her mother, serious diseases. a 30-year-old emergency department nurse. The In that a comprehensive history and physical ex- mother, who is well known to the pediatrician to be amination did not indicate an organic cause, the a competent and attentive caregiver, appears unchar- pediatrician reasoned that the most likely cause of acteristically tired. They are accompanied by the 18- her failure to thrive was an unintentional caloric month-old and 4-year-old siblings because child care deprivation secondary to maternal stress and ex- was unavailable, and her husband has been out of haustion. Christine’s mother and the pediatrician town on business for the last 5 weeks. When the discussed how maternal stress, fatigue, and depres- pediatrician comments, “You look exhausted. It must sion could hinder the let-down reflex and reduce the be really tough to care for 3 young children,” the availability of an adequate milk supply, as well as mother appears relieved that attention was given to make it difficult to maintain regular feeding sessions. her needs. She reports that she has not been getting The pediatrician recommended obtaining help with much sleep because Christine wakes up for 2 or more child care and household responsibilities. The evening feedings and the toddler is now awakening mother was also encouraged to consume adequate at night. -

A Dose-Response Relationship Between Organic Mercury Exposure from Thimerosal-Containing Vaccines and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 9156-9170; doi:10.3390/ijerph110909156 OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health ISSN 1660-4601 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph Article A Dose-Response Relationship between Organic Mercury Exposure from Thimerosal-Containing Vaccines and Neurodevelopmental Disorders David A. Geier 1, Brian S. Hooker 2, Janet K. Kern 1,3, Paul G. King 4, Lisa K. Sykes 4 and Mark R. Geier 1,* 1 Institute of Chronic Illnesses, Inc., 14 Redgate Ct., Silver Spring, MD 20905, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (D.A.G.); [email protected] (J.K.K.) 2 Department of Biology, Simpson University, 2211 College View Dr., Redding, CA 96003, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, 5353 Harry Hine Blvd., Dallas, TX 75390, USA 4 CoMeD, Inc., 14 Redgate Ct., Silver Spring, MD 20905, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (P.G.K.); [email protected] (L.K.S.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-301-989-0548; Fax: +1-301-989-1543. Received: 12 July 2014; in revised form: 7 August 2014 / Accepted: 26 August 2014 / Published: 5 September 2014 Abstract: A hypothesis testing case-control study evaluated concerns about the toxic effects of organic-mercury (Hg) exposure from thimerosal-containing (49.55% Hg by weight) vaccines on the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDs). Automated medical records were examined to identify cases and controls enrolled from their date-of-birth (1991–2000) in the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) project. -

Environmental Enteric Dysfunction and Growth Failure/Stunting In

Environmental Enteric Dysfunction and Growth Failure/Stunting in Global Child Health Victor Owino, PhD,a Tahmeed Ahmed, PhD,b Michael Freemark, MD, c Paul Kelly, MD, d, e Alexander Loy, PhD,f Mark Manary, MD, g Cornelia Loechl, PhDa Approximately 25% of the world’s children aged <5 years have stunted abstract growth, which is associated with increased mortality, cognitive dysfunction, and loss of productivity. Reducing by 40% the number of stunted children is a global target for 2030. The pathogenesis of stunting is poorly understood. Prenatal and postnatal nutritional deficits and enteric and systemic a International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Austria; infections clearly contribute, but recent findings implicate a central role bInternational Centre for Diarrhoeal Research, Bangladesh, for environmental enteric dysfunction (EED), a generalized disturbance Dhaka, Bangladesh; cDivision of Pediatric Endocrinology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina; of small intestinal structure and function found at a high prevalence in dUniversity of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia; eBlizard Institute, children living under unsanitary conditions. Mechanisms contributing Queen Mary University of London, London, United Kingdom; fDepartment of Microbiology and Ecosystem Science, to growth failure in EED include intestinal leakiness and heightened Research Network “Chemistry meets Microbiology, ” permeability, gut inflammation, dysbiosis and bacterial translocation, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria; and gWashington systemic inflammation, -

Diet Therapy and Phenylketonuria 395

61370_CH25_369_376.qxd 4/14/09 10:45 AM Page 376 376 PART IV DIET THERAPY AND CHILDHOOD DISEASES Mistkovitz, P., & Betancourt, M. (2005). The Doctor’s Seraphin, P. (2002). Mortality in patients with celiac dis- Guide to Gastrointestinal Health Preventing and ease. Nutrition Reviews, 60: 116–118. Treating Acid Reflux, Ulcers, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Shils, M. E., & Shike, M. (Eds.). (2006). Modern Nutrition Diverticulitis, Celiac Disease, Colon Cancer, Pancrea- in Health and Disease (10th ed.). Philadelphia: titis, Cirrhosis, Hernias and More. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins. Nevin-Folino, N. L. (Ed.). (2003). Pediatric Manual of Clin- Stepniak, D. (2006). Enzymatic gluten detoxification: ical Dietetics. Chicago: American Dietetic Association. The proof of the pudding is in the eating. Trends in Niewinski, M. M. (2008). Advances in celiac disease and Biotechnology, 24: 433–434. gluten-free diet. Journal of American Dietetic Storsrud, S. (2003). Beneficial effects of oats in the Association, 108: 661–672. gluten-free diet of adults with special reference to nu- Paasche, C. L., Gorrill, L., & Stroon, B. (2004). Children trient status, symptoms and subjective experiences. with Special Needs in Early Childhood Settings: British Journal of Nutrition, 90: 101–107. Identification, Intervention, Inclusion. Clifton Park: Sverker, A. (2005). ‘Controlled by food’: Lived experiences NY: Thomson/Delmar. of celiac disease. Journal of Human Nutrition and Patrias, K., Willard, C. C., & Hamilton, F. A. (2004). Celiac Dietetics, 18: 171–180. Disease January 1986 to March 2004, 2382 citations. Sverker, A. (2007). Sharing life with a gluten-intolerant Bethesda, MD: United States National Library of person: The perspective of close relatives. -

Stunted Growth in Children from Fetal Life to Adolescence

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 1453 Stunted growth in children from fetal life to adolescence Risk factors, consequences and entry points for prevention - Cohort studies in rural Bangladesh PERNILLA SVEFORS ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6206 ISBN 978-91-513-0305-5 UPPSALA urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-347524 2018 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Gustavianum, Akademigatan 3, Uppsala, Friday, 25 May 2018 at 13:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Faculty of Medicine). The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Docent Torbjörn Lind (Umeå Universitet). Abstract Svefors, P. 2018. Stunted growth in children from fetal life to adolescence. Risk factors, consequences and entry points for prevention - Cohort studies in rural Bangladesh. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 1453. 73 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-513-0305-5. Stunted growth affects one in four children under the age of five years and comes with great costs for the child and society. With an increased understanding of the long-term consequences of chronic undernutrition the reduction of stunted growth has become an important priority on the global health agenda. WHO has adopted a resolution to reduce stunting by 40% by the year 2025 and to reduce stunting is one of the targets under the Sustainable Development Goals. The aim of this thesis was to study linear growth trajectories, risk factors and consequences of stunting and recovery of stunting from fetal life to adolescence in a rural Bangladeshi setting and to assess the cost-effectiveness of a prenatal nutrition intervention for under-five survival and stunting. -

WHA Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Stunting Policy Brief

WHA Global Nutrition Targets 2025: 1 Stunting Policy Brief TARGET: 40% reduction in the number of children under-5 who are stunted WHO/Antonio Suarez Weise What’s at stake In 2012, the World Health Assembly Resolution 65.6 endorsed a Comprehensive implementation plan on maternal, infant and young child nutrition1, which specified six global nutrition targets for 20252. This policy brief covers the first target: a 40% reduction in the number of children under-5 who are stunted. The purpose of this policy brief is to increase attention to, investment in, and action for a set of cost-effective interventions and policies that can help Member States and their partners in reducing stunting rates among children aged under 5 years. Childhood stunting is one of the most significant be stunted in 2025. Therefore, further investment impediments to human development, globally and action are necessary to the 2025 WHA target of affecting approximately 162 million children under reducing that number to 100 million. the age of 5 years. Stunting, or being too short for one’s age, is defined as a height that is more than Stunting is a well-established risk marker of poor two standard deviations below the World Health child development. Stunting before the age of 2 years 3 predicts poorer cognitive and educational outcomes Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards median . 5,6 It is a largely irreversible outcome of inadequate in later childhood and adolescence , and has nutrition and repeated bouts of infection during significant educational and economic consequences the first 1000 days of a child’s life. -

Promoting Early Child Development Withtyler Vaivada, Msc, Interventionsa Michelle F

Promoting Early Child Development WithTyler Vaivada, MSc, Interventions a Michelle F. Gaffey, MSc, a Zulfiqar A. Bhutta, in PhD a,Health b and CONTEXT: Nutrition: A Systematic Reviewabstract Although effective health and nutrition interventions for reducing child mortality and morbidity exist, direct evidence of effects on cognitive, motor, and psychosocial OBJECTIVE: development is lacking. To review existing evidence for health and nutrition interventions affecting direct DATA SOURCES: measures of (and pathways to) early child development. Reviews and recent overviews of interventions across the continuum of care and STUDY SELECTION: component studies. We selected systematic reviews detailing the effectiveness of health or nutrition interventions that have plausible links to child development and/or contain direct DATA EXTRACTION: measures of cognitive, motor, and psychosocial development. RESULTS: A team of reviewers independently extracted data and assessed their quality. Sixty systematic reviews contained the outcomes of interest. Various interventions reduced morbidity and improved child growth, but few had direct measures of child development. Of particular benefit were food and micronutrient supplementation for mothers to reduce the risk of small for gestational age and iodine deficiency, strategies to reduce iron deficiency anemia in infancy, and early neonatal care (appropriate resuscitation, delayed cord clamping, and Kangaroo Mother Care). Neuroprotective interventions for imminent preterm birth showed the largest effect sizes (antenatal corticosteroids for developmental delay: risk ratio 0.49, 95% confidence interval 0.24 to 1.00; magnesium LIMITATIONS: sulfate for gross motor dysfunction: risk ratio 0.61, 95% confidence interval 0.44 to 0.85). Given the focus on high-quality studies captured in leading systematic reviews, CONCLUSIONS: only effects reported within studies included in systematic reviews were captured. -

Intervention Ideas for Infants, Toddlers, Children, and Youth Impacted by Opioids

TOPICAL ISSUE BRIEF Intervention IDEAs for Infants, Toddlers, Children, and Youth Impacted by Opioids Overview Prevalence The abuse of opioids—such as heroin and various prescription drugs commonly prescribed for pain (e.g., oxycodone, hydrocodone, and fentanyl)—has rapidly gained attention across the United States as a public health crisis. Youth may be exposed to opioids in a variety of ways, including but not limited to infants born to mothers who took opioids during pregnancy; children mistakenly consuming opioids (perhaps thinking they are candy); teenagers taking opioids from an illicit street supply; or, more commonly, teenagers being given opiates for free by a friend or relative.1,2 Even appropriate opioid use among adolescents and young adults to treat pain may slightly increase their risk of later opioid misuse.3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have identified opioid abuse as an epidemic, noting that opioids impact and affect all communities and age groups.4 Between 1997 and 2012, 13,052 children were hospitalized for poisonings caused by oxycodone, Percocet (a combination of acetaminophen and oxycodone), codeine, and other prescription opioids.5 Every 25 minutes, an infant is born suffering from opioid withdrawal, and an estimated 21,732 infants were born in 2012 with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), a drug withdrawal syndrome.6 According to data from 2014, approximately 28,000 adolescents had used heroin within the past year, 16,000 were current heroin users, and 18,000 had a heroin use disorder.7 At the same time, relatively few data are available about the effects of opiates on the U.S. -

Growth and Development and Their Environmental and Biological

J Pediatr (Rio J). 2016;92(3):241---250 www.jped.com.br ORIGINAL ARTICLE Growth and development and their environmental ଝ and biological determinants ∗ Kelly da Rocha Neves, Rosane Luzia de Souza Morais , Romero Alves Teixeira, Priscilla Avelino Ferreira Pinto Postgraduate Program in Health, Society and Environment (SaSA), Universidade Federal dos Vales do Jequitinhonha e Mucuri (UFVJM), Unaí, MG, Brazil Received 25 March 2015; accepted 5 August 2015 Available online 6 January 2016 KEYWORDS Abstract Objective: To investigate child growth, cognitive/language development, and their environ- Failure to thrive; mental and biological determinants. Child development; Methods: This was a cross-sectional, predictive correlation study with all 92 children aged Child health 24---36 months who attended the municipal early childhood education network in a town in the Vale do Jequitinhonha region, in 2011. The socioeconomic profile was determined using the questionnaire of the Associac¸ão Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa. The socio-demographicand maternal and child health profiles were created through a self-prepared questionnaire. The height-for-age indicator was selected to represent growth. Cognitive/language development was assessed through the Bayley Scale of Infant and Toddler Development. The quality of educa- tional environments was assessed by Infant/Toddler Environment Scale; the home environment was assessed by the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment. The neighbor- hood quality was determined by a self-prepared questionnaire. A multivariate linear regression analysis was performed. Results: Families were predominantly from socioeconomic class D, with low parental educa- tion. The prevalence of stunted growth was 14.1%; cognitive and language development were below average at 28.6% and 28.3%, respectively. -

Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths: Early Childhood

Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths: Early Childhood CANS: EC Supplemental Guide A Support for the CANS (Early Childhood) Information Integration Tool for Young Children Ages Birth to Five SET is part of the System of Care Initiative, within the Allegheny County Department of Human Services, Office of Behavioral Health Stacey Cornett, Copyright 2007. Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths: Early Childhood (CANS:EC) Section One: Child Strengths This section focuses on the attributes, traits, talents and skills of the child that can be useful in developing a strength-based treatment plan. Within a systems of care approach identifying strengths is considered an essential part of the process (Miles, P., Burns, E.J., Osher, T.W., Walker, J.S., 2006). A focus on strengths that both the child and the family have to offer allows for a climate of hope and optimism and has been proven to engage families at a higher level. Strength-based assessment has been defined as, “the measurement of those emotional and behavioral skills, competencies, and characteristics that create a sense of personal accomplishment; contribute to satisfying relationships with family members, peers, and adults; enhance one’s ability to deal with adversity and stress; and promote one’s personal, social, and academic development” (Epstein & Sharma, 1998, p.3). The benefits of a strength- based assessment include involving parents and children in a service planning experience that builds on what a child and family are doing well, facilitates positive expectations for the child, and empowers family members to take responsibility for the decisions that will affect their child (Johnson & Friedman, 1991; Saleebey, 1992). -

The Child with Failure to Thrive

The Child with Failure to Thrive Bonnie Proulx, MSN, APRN, PNP Pediatric Gastroenterology Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth Manchester, NH DISCLOSURES None of the planners or presenters of this session have disclosed any conflict or commercial interest The Child with Failure to Thrive OBJECTIVES: 1. Review assessment and appropriate diagnostic testing for children who fail meet expected growth 2. Discuss various causes of failure to thrive. 3. Identify appropriate referrals for children with failure to thrive. Definition • Inadequate physical growth diagnosed by observation of growth over time on a standard growth chart Definition • More than 2 standard deviations below mean for age • Downward trend in growth crossing 2 major percentiles in a short time • Comparison of height and weight • Not a diagnosis but a finding Pitfalls • Some children are just tiny • Familial short stature children may cross percentiles to follow genetic predisposition • Normal small children may be diagnosed later given already tiny Frequency • Affects 5-10% of children under 5 in developing countries • Peak incidence between 9 and 24 months of age • Uncommon after the age of 5 What is normal growth • Birth to 6 months, a baby may grow 1/2 to 1 inch (about 1.5 to 2.5 centimeters) a month • 6 to 12 months, a baby may grow 3/8 inch (about 1 centimeter) a month • 2nd year of life 4-6 inches • 3rd year 3-4 inches • Annual growth until pre-puberty 2-3 inches per year Normal weight gain • Birth to 6 months-gain 5 to 7 ounces a week. • 6 to 12 months -gain 3 to 5 ounces (about 85 to 140 grams) a week. -

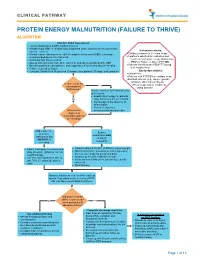

Protein Energy Malnutrition (Failure to Thrive) Algorithm

CLINICAL PATHWAY PROTEIN ENERGY MALNUTRITION (FAILURE TO THRIVE) ALGORITHM Conduct Initial Assessment • History and physical (H&P), nutrition focused • Weight height, BMI, % of ideal body weight and exam: assess severity (symmetric edema = severe) Inclusion criteria: • • Consider basic labs based on H&P; A complete blood count (CBC) is strongly Children newborn to 21 years of age • recommended due to risk of anemia Inpatients admitted for evaluation and • Additional labs based on H&P treatment of Protein Energy Malnutrition • Assess micronutrients: iron, zinc, vitamin D, and others as indicated by H&P (PEM) or Failure to thrive (FTT) OR • • Baseline potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium if concerned about re-feeding Patients identified with PEM/FTT during • Calorie count up to 3 days their hospital stay. • Consults: Social Work, Registered Dietician, Occupational Therapy, and Lactation Exclusion criteria: • Outpatients • Patients with FTT/PEM secondary to an identified concern (e.g., cancer, genetic condition, other chronic illness). Is there a risk for •Pts w/ suspected or confirmed micronutrient Yes eating disorder deficiencies? Initiate treatment for micronutrients deficiencies: • Empiric zinc therapy for patients No older than 6 months for 1 month • Iron therapy in the absence of inflammation • Vitamin D and other What are the micronutrients based on labs degrees of malnutrition and risk of refeeding? Mild, moderate, Severe or severe malnutrition AND malnutrition but at risk of NO RISK of refeeding refeeding • • Initiate feeding per recommended Initiate feeding at 30-50% of RDA for current weight • daily allowance (RDA) for current Monitor potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium weight and age once to twice a day for a total of 4 days • • Use PO route if patient is able to Advance by 10-20% if labs are normal • take 70% of estimated calories If labs abnormal hold off on advancing feed until orally corrected • Start thiamine Advance calories to meet level for catch up growth.