Ch06: ENDODONTIC DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seltzer and Benders Dental Pulp 2012 4.Pdf

Effects of Thermal and Mechanical Challenges burs).19 Collectively, these results indicate that pulpal 8 HS air reactions to various restorative procedures17-19 are not necessarily caused by excessive heat production. However, it is difficult to precisely position tempera ture sensors to detect heat generated during cut ting. In addition, the poor thermal conductivity of dentin can result in thermal burns to surface dentin without much change in pulpal temperature.20 HS air-water Pulpal reactions to restorative procedures may / - - - ...... in part be caused indirectly. It is possible that a high LS air-water surface temperature can thermally expand the den tinal fluid in the tubules immediately beneath poorly -5 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 irrigated burs. If the rate of expansion of dentinal Time(s) fluid is high, the fluid flow across odontoblast pro cesses, especially where the odontoblast cell body fills the tubules in predentin, may create shear forces Fig 15-2 Changes in pulpal temperature during low-speed (LS) and high sufficiently large to tear the cell membrane21 and speed (HS) cavity preparation with and without air-water cooling. (Modified from Zach and Cohen10 with permission.) induce calcium entry into the ce//,22 possibly leading to cell death.23 This hypothesis suggests that ther mally induced fluid shifts across tubules serve as the transduction mechanism for pulp cell injury without causing much change in pulpal temperature. An additional factor that can cause pulpal irrita that produced in pulp tissues. However, the out tion is evaporative fluid flow.24 Blowing air on dentin come may be influenced by the fact that the blood causes rapid outward fluid flow that can induce the flow per milligram of tissue is higher in the periodon same cell injury as the inward fluid flow caused by tal ligament (PDL) than in the pulp.9 heat. -

Clinical Implications of Calcifying Nanoparticles in Dental Diseases: a Critical Review

International Journal of Nanomedicine Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article REVIEW Clinical implications of calcifying nanoparticles in dental diseases: a critical review Mohammed S Alenazy1 Background: Unknown cell-culture contaminants were described by Kajander and Ciftçioğlu Hezekiah A Mosadomi2,3 in 1998. These contaminants were called nanobacteria initially and later calcifying nanoparticles (CNPs). Their exact nature is unclear and controversial. CNPs have unique and unusual charac- 1Restorative Dentistry Department, 2Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology teristics, which preclude placing them into any established evolutionary branch of life. 3 Department, Research Center, Riyadh Aim: The aim of this systematic review was to assess published data concerning CNPs since Colleges of Dentistry and Pharmacy, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia 1998 in general and in relation to dental diseases in particular. Materials and methods: The National Library of Medicine (PubMed) and Society of Pho- tographic Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE) electronic and manual searches were conducted. Nanobacteria and calcifying nanoparticles were used as keywords. The search yielded 135 full-length papers. Further screening of the titles and abstracts that followed the review criteria resulted in 43 papers that met the study aim. Conclusion: The review showed that the existence of nanobacteria is still controversial. Some inves- tigators have described a possible involvement of CNPs in pulpal and salivary gland calcifications, as well as the possible therapeutic use of CNPs in the treatment of cracked and/or eroded teeth. Keywords: calcifying nanoparticles, nanobacteria, sialolith, pulp stone, enamel repair Introduction Unknown cell-culture contaminants were first described by Kajander and Ciftçiog˘lu in 1998. -

Denticles. a Literature Review

Prog Health Sci 2015, Vol 5, No2 Denticles – literature review Denticles. A literature review Kisiel M, Laszewicz J, Frątczak P, Dąbrowska B, Pietruska M, Dąbrowska E. Department of Social and Preventive Dentistry Medical University of Bialystok, Poland Social and Preventive Dentistry Research Club under the supervision of Ewa Dąbrowska ABSTRACT __________________________________________________________________________________________ Denticles are pulp degenerations in the form of obtain proper access to the pulp chamber bottom and calcified deposits of mineral salts, usually found in the canal orifices. There is also the increased risk of molars and lower incisors, as well as in impacted bending or breaking the endodontic instruments. teeth and deciduous molars. Denticles may come in Sometimes, denticles fill the entire space of the tooth various sizes, from microscopic particles to larger chamber and pushing the pulp to the edges of the mass that almost obliterate the pulp chamber and are chamber. Denticles can cause pain due to the visible only on X-ray images. Denticles form as a pressure on the nerves and blood vessels supplying result of chronic inflammatory lesions, but may also the internal tissue of the tooth. The presence of large be caused by injuries and conservative treatment. denticles might eventually lead to necrosis of the They are most frequently found in necrotic foci. pulp. Denticles accompany certain diseases, such as Denticles may cause problems for root canal dentin dysplasia, odontodysplasia or Albright treatment, as their presence might make it difficult to hereditary dystrophy. Key wards: teeth, denticles, _________________________________________________________________________________________ *Corresponding author: Ewa Dąbrowska Department of Social and Preventive Dentistry Medical University of Bialystok ul. -

Denture Technology Curriculum Objectives

Health Licensing Agency 700 Summer St. NE, Suite 320 Salem, Oregon 97301-1287 Telephone (503) 378-8667 FAX (503) 585-9114 E-Mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.Oregon.gov/OHLA As of July 1, 2013 the Board of Denture Technology in collaboration with Oregon Students Assistance Commission and Department of Education has determined that 103 quarter hours or the equivalent semester or trimester hours is equivalent to an Associate’s Degree. A minimum number of credits must be obtained in the following course of study or educational areas: • Orofacial Anatomy a minimum of 2 credits; • Dental Histology and Embryology a minimum of 2 credits; • Pharmacology a minimum of 3 credits; • Emergency Care or Medical Emergencies a minimum of 1 credit; • Oral Pathology a minimum of 3 credits; • Pathology emphasizing in Periodontology a minimum of 2 credits; • Dental Materials a minimum of 5 credits; • Professional Ethics and Jurisprudence a minimum of 1 credit; • Geriatrics a minimum of 2 credits; • Microbiology and Infection Control a minimum of 4 credits; • Clinical Denture Technology a minimum of 16 credits which may be counted towards 1,000 hours supervised clinical practice in denture technology defined under OAR 331-405-0020(9); • Laboratory Denture Technology a minimum of 37 credits which may be counted towards 1,000 hours supervised clinical practice in denture technology defined under OAR 331-405-0020(9); • Nutrition a minimum of 4 credits; • General Anatomy and Physiology minimum of 8 credits; and • General education and electives a minimum of 13 credits. Curriculum objectives which correspond with the required course of study are listed below. -

DENTAL PULP the Pulp Proper but Are in Small Amounts and Not Well

DENTAL PULP 9 Diffuse collagen fibers Collagen bundles Collagen bundles Fig. 9.17 Collagen bundles in an older pulp organ. Trauma may also have contributed to collagen in this pulp. the pulp proper but are in small amounts and not well areas of the body, and the blood pressure is quite high. The characterized. diameter of the arteries varies from 50 to 100 m, which equals the size of arterioles in other areas of the body. These Vascularity vessels have three layers: the inner lining, or intima, which The pulp organ is highly vascularized, with vessels arising consists of oval or squamous-shaped endothelial cells sur- from the external carotid arteries to the superior and inferior rounded by a closely associated fibrillar basal lamina; a alveolar arteries. It drains by the same veins. Although the middle layer or media, which consists of muscle cells from periodontal and pulpal vessels both originate from these one to three cell layers thick (Fig. 9-20 ); and an outer layer, vessels, their walls are different. The walls of the periodontal or adventitia, which consists of a sparse layer of collagen and pulpal vessels become quite thin as they enter the pulp, fibers forming a loose network around the larger arteries. because the pulp is protected within a hard, unyielding con- Smaller arterioles with a single layer of muscle cells range tainer of dentin. These thin-walled arteries and arterioles from 20 to 30 m, and terminal arterioles of 10 to 15 m enter the apical canal and pursue a direct route up the root are also present. -

Assessment of the Frequency and Correlation of Carotid Artery

Clinical and Experimental Health Sciences Assessment of The Frequency and Correlation of Carotid Artery Calcifications and Pulp Stones with Idiopathic Osteosclerosis Using Digital Panoramic Radiographs Sema Sonmez Kaplan , Tuna Kaplan , Guzide Pelin Sezgin Department of Endodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Biruni University, Istanbul, Turkey. Correspondence Author: Sema Sonmez Kaplan E-mail: [email protected] Received: 15.12.2020 Accepted: 25.03.2021 ABSTRACT Objective: The aim of this study was to assess the correlation of carotid artery calcifications (CACs) and pulp stones with idiopathic osteosclerosis (IO) using digital panoramic radiographs (DPRs) to determine whether pulp stones or IO might be possible indicators of the presence of CACs. Methods: In total, DPRs of 1207 patients (645 females and 562 males) taken within 2018 were retrospectively evaluated to determine the prevalence of CACs, pulp stones and IO according to age and sex. Statistical analysis was performed using chi-square test and Fisher’s exact chi- square test. Results: In total, 287 (23.8%) patients had at least one pulp stone, and 64 (5.3%) patients had CACs. The negative/negative (-/-) status of CACs/ pulp stones was significantly higher in the 18–29 years age group than in the 30–39, 40–49, 50–59 and ≥60 years age groups (p<0.05). It was also significantly higher in males than females (p<0.05). Sixteen (1.3%) patients had IO, which was related to right mandibular molars in all cases. Patients with CACs had a significantly higher prevalence of IO (6.3%) than those without CACs (1%) (p<0.05). There was no statistically significant association between pulp stones and the presence of IO and CACs (p>0.05). -

2021-2022 ADC Catalog

American Denturist College 145 E. 12th Alley Eugene OR 97401 Office 541.654.5885 Toll Free 800.544.6267 https://adc.edu Denturist Diploma & Bachelor’s of Technical Science Degree in Denturism College Catalog Page 1 of 143 (Effective Date: January 2021 through January 2022) Table of Contents College Information .............................................................................................................................................. 7 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 About Us .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Denturist and Denturist-related Education ....................................................................................... 8 General Education Goals ........................................................................................................................... 8 Administrative Staff and Faculty ........................................................................................................... 8 Educators ........................................................................................................................................................ 9 Advisory Board .......................................................................................................................................... 11 Authorization and Accrediting -

Pulp Calcification

It is a localized or generalized condition of pulp tissue characterized by the presence of pulp stone in the pulp tissue in the form of calcified bodies. Site: coronal or radicular dentine. Size: variable Sign and symptoms: painless Radiographic features: Radio opaque mass of variable size in pulp chamber and pulp canal. HISTOLOGICAL TYPES True pulp stone: consist of dentinal tubules. False pulp stones: consists of concentric calcified rings. Free pulp stones: is freely located in pulp chamber and pulp canals. Attached pulp stone: is adherent to dentine wall. Embeded pulp stone: is surrounded by secondary dentine. complications It can interferes with root canal treatment. Causes pain if it impinges on major nerves of pulp. Pulp necrosis It is an irreversible condition of pulp tissue characterized by dead pulp tissue and degeneration (necrosis). Aetiology Severely irritant agent. Sign and symptoms: painfull Duration: 10-15min, severe and short. Precipitating factors of pain: hot and cold agents Nature of pain: Throbbing, continuous and radiating. Pain stops as precipitating factors are removed. Periapical lesions Periapical abscess Periapical granuloma Periapical cyst Aetiology of periapical pathosis Presence of open or closed pulpitis Virulence of involved organisms Extent of sclerosis of detinal tubules Competency of the host immune response. Periapical granuloma It refers to a mass of chronically inflammed granulation tissue at the apex of a non vital tooth. May arise either after an acute condition like periapial abscess becomes quiet or may arise denovo. Importance: These lesions are not static and may transform into periapical cyst or undergo acute excerbation. Clinical features Mostly asymptomatic. Pain and sensitivity developes if it undergoes acute excerbation. -

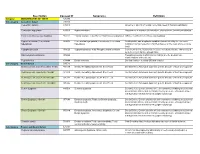

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition Category ABNORMALITIES OF TEETH 426390 Subcategory Cementum Defect 399115 Cementum aplasia 346218 Absence or paucity of cellular cementum (seen in hypophosphatasia) Cementum hypoplasia 180000 Hypocementosis Disturbance in structure of cementum, often seen in Juvenile periodontitis Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia 958771 Familial multiple cementoma; Florid osseous dysplasia Diffuse, multifocal cementosseous dysplasia Hypercementosis (Cementation 901056 Cementation hyperplasia; Cementosis; Cementum An idiopathic, non-neoplastic condition characterized by the excessive hyperplasia) hyperplasia buildup of normal cementum (calcified tissue) on the roots of one or more teeth Hypophosphatasia 976620 Hypophosphatasia mild; Phosphoethanol-aminuria Cementum defect; Autosomal recessive hereditary disease characterized by deficiency of alkaline phosphatase Odontohypophosphatasia 976622 Hypophosphatasia in which dental findings are the predominant manifestations of the disease Pulp sclerosis 179199 Dentin sclerosis Dentinal reaction to aging OR mild irritation Subcategory Dentin Defect 515523 Dentinogenesis imperfecta (Shell Teeth) 856459 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield I 977473 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield II 976722 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; -

289 Abstract

Atatürk Üniv. DiĢ Hek. Fak. Derg. Araştırma/ ResearchDAĞISTAN, Article MĠLOĞLU J Dent Fac Atatürk Uni Cilt:25, Sayı:3, Yıl: 2015, Sayfa: 289-293 THE RELATIONSHIP OF THE CHRONIC RENAL FAILURE WITH CAROTID ARTERY CALCIFICATIONS, DENTAL PULP CALCIFICATIONS AND DENTAL PULP STONES KRONİK BÖBREK YETMEZLİĞİ İLE KAROTİD ARTER KALSİFİKASYONLARI, DENTAL PULPA KALSİFİKASYONLARI VE DENTAL PULPA TAŞLAR I ARASINDAKİ İLİŞKİ Doç. Dr. Saadettin DAĞISTAN* Doç. Dr. Özkan MİLOĞLU* Makale Kodu/Article code: 2396 Makale Gönderilme tarihi: 17.09.2015 Kabul Tarihi: 10.12.2015 ABSTRACT ÖZET Aim: The aim of this study was to investigate the existence of carotid artery calcifications in dental Amaç: Bu çalıĢmanın amacı diyalize giren kronik panoramic radiographs and dental pulp calcifications böbrek yetmezliği olan hastalar ile sağlıklı bireyleri, together with dental pulp stones in periapical panoramik radyografilerde karotid arter kalsifikasyonu radiographs in patients with chronic renal failure ve periapikal radyografilerdeki pulpa kalsifikasyonu ve undergoing haemodialysis and healthy individuals, and pulpa taĢı varlığı açısından karĢılaĢtırarak incelemektir. to identify the relationship between the two groups. Materyal ve metot: ÇalıĢmaya kronik böbrek Material and method: A total of 115 cases (57 yetmezliği olup diyalize giren 57 ve sağlıklı 58 birey patients on haemodialysis for chronic renal failure and olmak üzere toplam 115 kiĢi dahil edilmiĢ ve bu 58 healthy individuals without any systemic disease) kiĢilerde panoramik radyografilerdeki karotid arter were included in the study. Carotid artery calcifications kalsifikasyonu ve periapikal radyografilerdeki pulpa in panoramic radiographs and dental pulp kalsifikasyonları ve pulpa taĢları araĢtırılmıĢtır. calcifications, and pulp stones in periapical Bulgular: Kontrol grubundaki bireylerin hiçbirinde radiographs were investigated. karotid arter kalsifikasyonu belirlenmemesine rağmen Results: None of the individuals in the control group diyalize giren 57 hastanın 3’ünde (5,26%) karotid had calcifications of carotid artery. -

Prevalence and Clinical Characteristics of Teeth Extracted with a Diagnosis of Cracked Tooth: a Retrospective Study

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2017 Prevalence and Clinical Characteristics of Teeth Extracted with a Diagnosis of Cracked Tooth: A Retrospective Study Riley B. Sturgill Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Dental Public Health and Education Commons, and the Endodontics and Endodontology Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4820 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Riley B. Sturgill, DMD 2017 All Rights Reserved Prevalence and Clinical Characteristics of Teeth Extracted with a Diagnosis of Cracked Tooth: A Retrospective Study A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Dentistry at Virginia Commonwealth University. by Riley B. Sturgill, DMD, BS, King University, 2008 DMD, Arizona School of Dentistry & Oral Health, 2013 Director: Garry L. Myers, DDS Director, Advanced Education Program in Endodontics, Department of Endodontics, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Dentistry Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May, 2017 ii Acknowledgement The author wishes to thank several people. I would like to thank my husband, family, and friends for all of their many prayers, love, and support. I would also like to thank Drs. Best, Myers, and Coe for their help and guidance with this project. iii Table of Contents List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. v List of Figures ............................................................................................................................... -

Health Sciences

Clinical and Experimental Contents Health Sciences RESEARCH ARTICLES Naringenin Reduces Hepatic Inflammation and Apoptosis Induced by Vancomycin in Rats ...............................................191 Zuhal Uckun Sahinogullari, Sevda Guzel, Necmiye Canacankatan, Cem Yalaza, Deniz Kibar, Gulsen Bayrak Nicotine Dependence Levels of Individuals Applying to a Family Health Center and Their Status of Being Affected by Warnings on Cigarette Packs ............................................................................................................................................................199 Erdal Akdeniz, Selma Oncel Urine Influences Growth and Virulence Gene Expressions in Uropathogenic E. coli: A Comparison with Nutrient Limited Medium ...........................................................................................................................................................................209 Fatma Kalayci Yuksek, Defne Gumus, Gulsen Uz, Ozlem Sefer, Emre Yoruk, Mine Ang Kucuker Turkish Adaptation of Attention Function Index: A Validity and Reliability Study ..............................................................215 Nese Uysal, Gulcan Bagcivan, Filiz Unal Toprak, Yeter Soylu, Bektas Kaya Effect of Web-Based Training on Complication Control and Quality of Life of Spinal Cord Damaged Individuals: Randomized Controlled Trial .................................................................................................................................................................220 Elif Ates, Naile Bilgili