CHAPTER I1 NATIW COCHHN and the Hhntemand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accused Persons Arrested in Alappuzha District from 17.05.2020To23.05.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Alappuzha district from 17.05.2020to23.05.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cr No-792 / 2020 U/s188, 269 IPC & 118(a) of KP KAMBIVALAPPIL Act & Sec. HOUSE 23-05- 4(2)(a), BAILED BY 1 ANEESH SHAJI 26 MaleKAKKAZHOM PURAKKAD 2020 AMBALAPUZHAJIJIN JOSEPH 4(2)(e), POLICE AMBALAPUZHA 21:10 4(2)(h) r/w 5 NORTH P/W - 15 of Kerala Epidemic Diseases Ordinance 2020 Cr No-792 / 2020 U/s188, 269 IPC & 118(a) of KP PUTHUVAL Act & Sec. 23-05- PURAKKAD PO 4(2)(a), BAILED BY 2 SHAMEER KUNJUMON38 Male PURAKKAD 2020 AMBALAPUZHAJIJIN JOSEPH PURAKKAD P/W - 4(2)(e), POLICE 21:10 17 4(2)(h) r/w 5 of Kerala Epidemic Diseases Ordinance 2020 Cr No-792 / 2020 U/s188, 269 IPC & 118(a) of KP MULLATH Act & Sec. VALAPPU 23-05- 4(2)(a), BAILED BY 3 ASHKAR ABDUL KHADER27 MaleTHIRUVAMPADY PURAKKAD 2020 AMBALAPUZHAJIJIN JOSEPH 4(2)(e), POLICE ALAPPUZHA 21:10 4(2)(h) r/w 5 MUNICIPAL of Kerala Epidemic Diseases Ordinance 2020 Cr No-792 / 2020 U/s188, 269 IPC & 118(a) of KP PALLIPURATHU Act & Sec. MADOM 23-05- 4(2)(a), BAILED BY 4 BABU GEORGEGEORGE 52 MaleTHAKAZHY PO PURAKKAD 2020 AMBALAPUZHAJIJIN JOSEPH 4(2)(e), POLICE THAKAZHY P/W - 21:10 4(2)(h) r/w 5 5 of Kerala Epidemic Diseases Ordinance 2020 Cr No-792 / 2020 U/s188, 269 IPC & 118(a) of KP KUTTIKKAL Act & Sec. -

Supremacy of Dutch in Travancore (1700-1753)

http://www.epitomejournals.com Vol. 4, Issue 6, June 2018, ISSN: 2395-6968 SUPREMACY OF DUTCH IN TRAVANCORE (1700-1753) Dr. B. SHEEBA KUMARI, Assistant Professor, Department of History, S. T. Hindu College, Nagercoil - 629 002. ABSTRACT in Travancore especially the Dutch from 1700 to 1753 A.D. was noted worthy in Travancore, a premier princely state of the history of the state. In this context, this south India politically, occupied an paper high lights the part of the Dutch to important place in Travancore history. On attain the political supremacy in the eve of the eighteenth century the Travancore. erstwhile state Travancore was almost like KEYWORDS a political Kaleidoscope which was greatly Travancore, Kulachal, Dutch Army, disturbed by internal and external Ettuveettil Pillamar, Marthanda Varma, dissensions. The internal feuds coupled Elayadathu Swarupam with machinations of the European powers. Struggled for political supremacy RESEARCH PAPER Travancore the princely state became an attractive for the colonists of the west from seventeenth century onwards. The Portuguese, the Dutch and the English developed commercial relations with the state of Travancore1. Among the Europeans the Portuguese 70 BSK Impact Factor = 3.656 Dr. Pramod Ambadasrao Pawar, Editor-in-Chief ©EIJMR All rights reserved. http://www.epitomejournals.com Vol. 4, Issue 6, June 2018, ISSN: 2395-6968 were the first to develop commercial contacts with the princes, and establish and fortress in the regions2. Their possessions were taken over by the later adventurers, the Dutch3. The aim of the Dutch in the beginning of the seventeenth century was to take over the whole of the Portuguese trading empire in Asia. -

M. R Ry. K. R. Krishna Menon, Avargal, Retired Sub-Judge, Walluvanad Taluk

MARUMAKKATHAYAM MARRIAGE COMMISSION. ANSWERS TO INTERROGATORIES BY M. R RY. K. R. KRISHNA MENON, AVARGAL, RETIRED SUB-JUDGE, WALLUVANAD TALUK. 1. Amongst Nayars and other high caste people, a man of the higher divi sion can have Sambandham with a woman of a lower division. 2, 3, 4 and 5. According to the original institutes of Malabar, Nayars are divided into 18 sects, between whom, except in the last 2, intermarriage was per missible ; and this custom is still found to exist, to a certain extent, both in Travan core and Cochin, This rule has however been varied by custom in British Mala bar, in Avhich a woman of a higher sect is not now permitted to form Sambandham with a man of a lower one. This however will not justify her total excommuni cation from her caste in a religious point of view, but will subject her to some social disabilities, which can be removed by her abandoning the sambandham, and paying a certain fine to the Enangans, or caste-people. The disabilities are the non-invitation of her to feasts and other social gatherings. But she cannot be prevented from entering the pagoda, from bathing in the tank, or touch ing the well &c. A Sambandham originally bad, cannot be validated by a Prayaschitham. In fact, Prayaschitham implies the expiation of sin, which can be incurred only by the violation of a religious rule. Here the rule violated is purely a social one, and not a religious one, and consequently Prayaschitham is altogether out of the place. The restriction is purely the creature of class pride, and this has been carried to such an extent as to pre vent the Sambandham of a woman with a man of her own class, among certain aristocratic families. -

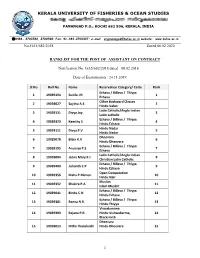

Ranklist for the Post of Assistant on Contract

KERALA UNIVERSITY OF FISHERIES & OCEAN STUDIES PANANGAD P.O., KOCHI 682 506, KERALA, INDIA 0484- 2703782, 2700598; Fax: 91-484-2700337; e-mail: [email protected] website: www.kufos.ac.in No.GA5/682/2018 Dated,06.02.2020 RANKLIST FOR THE POST OF ASSISTANT ON CONTRACT Notification No. GA5/682/2018 dated 08.02.2018 Date of Examination : 24.11.2019 Sl No Roll No Name Reservation Category/ Caste Rank Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 1 19039194 Sunila .M 1 Ezhava Other Backward Classes 2 19039027 Sajitha A.S 2 Hindu Valan Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 3 19039131 Divya Joy 3 Latin catholic Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 4 19039323 Keerthy S 4 Hindu Ezhava Hindu Nadar 5 19039111 Divya P.V 5 Hindu Nadar Dheevara 6 19039078 Bibin K.V 6 Hindu Dheevara Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 7 19039195 Anusree P.S 7 Ezhava Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 8 19039084 Jeena Mary K J 8 Christian Latin Catholic Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 9 19039403 Jishanth C.P 9 Hindu Ezhava Open Competetion 10 19039356 Nisha P.Menon 10 Hindu Nair Muslim 11 19039352 Shakira P.A. 11 Islam Muslim Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 12 19039041 Bindu.C.N 12 HIndu Ezhava Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 13 19039381 Beena N.K. 13 Hindu Thiyya Viswakarama 14 19039383 Rejana P.R. Hindu Vishwakarma, 14 Blacksmith Dheevara 15 19039013 Hitha Thanckachi Hindu Dheevara 15 1 16 Amrutha Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 16 19039336 Sundaram Hindu Ezhava Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 17 19039114 Mary Ashritha 17 Latin Catholic Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 18 19039120 Basil Antony K.J 18 Latin Catholic Dheevara 19 19039166 Thushara M.V 19 Deevara Sreelakshmi K Open Competetion 20 19039329 20 Nair Nair Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 21 19039373 Dileep P.R. -

Chapter Iv Traces of Historical Facts From

CHAPTER IV TRACES OF HISTORICAL FACTS FROM SANDESAKAVYAS & SHORT POEMS Sandesakavyas occupy an eminent place among the lyrics in Sanskrit literature. Though Valmiki paved the way in the initial stage it was Kalidasa who developed it into a perfect form of poetic literature. Meghasandesa, the unique work of Kalidasa, was re- ceived with such enthusiasam that attempts were made to emulate it all over India. As result there arose a significant branch of lyric literature in Sanskrit. Kerala it perhaps the only region which produced numerous works of real merit in this field. The literature of Kerala is full of poems of the Sandesa type. Literature can be made use of to yield information about the social history of a land and is often one of the main sources for reconstructing the ancient social customs and manners of the respective periods. History as a separate study has not been seriously treated in Sanskrit literature. Apart form literary merits, the Sanskrit literature of Kerala contains several historical accounts of the country with the exception of a few historical Kavyas, it is the Sandesakavyas that give us some historical details. Among the Sanskrit works, the Sandesa Kavya branch stands in a better position in this field (matter)Since it contains a good deal of historical materials through the description of the routes to be followed by the messengers in the Sandesakavyas. The Sandesakavyas play an impor- tant role in depicting the social history of their ages. The keralate Sandesakavyas are noteworthy because of the geographical, historical, social and cultural information they supply about the land. -

Kottayam Block Panchayat

Detailed Report on District wise Local Body Election Results District Name : Kottayam Block Panchayat Votes Valid InValid Votes in Local Body Sl.No Candidate Name Party Status Polled Votes Votes Favour 47 ssh¡w 1 sN¼v 6090 5917 173 1 tKm]n\mY³ ]nÅ BJP 224 Deposit Loss Vaikom Chembu Gopinathan Pilla 2 sI sI ctai³ CPI(M) 3323 Elected K K Ramesan 3 Fk. Un. kptcjv _m_p INC 2370 Non Elected S. D. Suresh Babu 2 {_ÒawKew 6172 5979 193 1 sI sNø³ CPI 2941 Elected Brahmamangalam K Chellappan 2 Fw sI cmP¸³ INC 2609 Non Elected M K Rajappan 3 jmPn BJP 429 Deposit Loss Shaji 3 adh³Xpcp¯v 6690 6527 163 1 tKm]meIrjvW³ \mbÀ INDEPENDENT 82 Deposit Loss Maravanthuruthu Gopalakrishnan Nair 2 AUz. ]n BÀ {]tamZv CPI(M) 3462 Elected Adv. P. R. Pramod 3 Fw. sI. jn_p INC 2983 Non Elected M. K. Shibu 4 ssh¡{¸bmÀ 6292 6111 181 1 cRvPn\n s]m¶¸³ INC 2282 Non Elected Vaikaprayar Ranjini Ponnappan 2 sseem cm[mIrjvW³ CPI 3829 Elected Laila Radhakrishnan 5 tXm«Iw 6758 6510 248 1 Fw. Un. _m_pcmPv CPI 4057 Elected Thottakam M .D. Baburaj 2 kmP³ sI sFk¡v INC 2453 Non Elected Sajan K Issac 6 Xebmgw 6082 5951 131 1 ]n. tcWp CPI(M) 3579 Elected Thalayazham P. Renu 2 kpPnX INC 2372 Non Elected Sujitha Page 1 of 323 Detailed Report on District wise Local Body Election Results District Name : Kottayam Block Panchayat Votes Valid InValid Votes in Local Body Sl.No Candidate Name Party Status Polled Votes Votes Favour 47 ssh¡w 7 CSbmgw 5541 5388 153 1 N{µnI CPI 2767 Elected Vaikom Idayazham Chandrika 2 `mh\ X¦¸³ INC 2621 Non Elected Bhavana Thankappan 8 sh¨qÀ 6233 6004 229 1 Pn. -

Environmental Impact of Sand Mining: a Cas the River Catchments of Vembanad La Southwest India

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF SAND MINING: A CAS THE RIVER CATCHMENTS OF VEMBANAD LA SOUTHWEST INDIA Thesis submitted to the COCHIN UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT UNDER THE FACULTY OF ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES BY SREEBHAS (Reg. No. 290 I) CENTRE FOR EARTH SCIENCE STUDIES THlRUVANANTHAPURAM - 695031 DECEMBER 200R Dedicated to my fBe[0 1/ea’ Tatfier Be still like a mountain and flow like a great river. Lao Tse DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis entitled “ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF SAND MINING: A CASE STUDY IN THE RIVER CATCHMENTS OF VEMBANAD LAKE, SOUTHWEST INDIA” is an authentic record of the research work carried out by me under the guidance of Dr. D Padmalal, Scientist, Environmental Sciences Division, Centre for Earth Science Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Management under the faculty of Environmental Studies of the Cochin University of Science and Technology. No part of it has been previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship or any other similar title or recognition of this or of any other University. ,4,/~=&P"9 SREEBHA S Thiruvananthapuram November, 2008 CENTRE FOR EARTH SCIENCE STUDIES Kerala State Council for Science, Technology & Environment P.B.No. 7250, Akkulam, Thiruvananthapuram - 695 031 , India CERTIFICATE This is to certify that this thesis entitled "ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF SAND MINING: A CASE STUDY IN THE RIVER CATCHMENTS OF VEMBANAD LAKE, SOUTHWEST INDIA" is an authentic record of the research work carried out by SREEBHA S under my scientific supervision and guidance, in Environmental Sciences Division, Centre for Earth Science Studies. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 23.04.2017 to 29.04.2017

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 23.04.2017 to 29.04.2017 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kakkattu House, Near Shameer M.K, 801/17 U/s. Morkulangara 25.4.17 SI of Police, 1 Raju K Neelakandan 59/17 Police Stn 279, 337, 338 CHRY Bail from PS Temple, Vazhappally, 11.30 AM Changanacherr IPC Changanacherry y Chiravalayil House, Shameer M.K, W/o. John 35/17 Kunnumpuram 25.4.17 12 800/17 U/s. SI of Police, 2 Binsi John Police Stn CHRY Bail from PS Jacob Female Bhagam, noon 279, 338 IPC Changanacherr Nedumkunnam y Shameer M.K, Ammanchiyil House, 791/17 U/s. Prasannakum 25.4.17 2 SI of Police, 3 Sreejesh 34/17 Puzhavath, Police Stn 279, 337, 338 CHRY Bail from PS ar PM Changanacherr Changanacherry IPC y Kaja Manzil, IE Nagar, 779/17 U/s. M.G Raju, Asst. 27.4.17 4 P.K Nazim Kunjumon 44/17 Chethipuzha, Puzhavath 279, 337, 338 CHRY Sub Inspector, Bail from PS 12.30 PM Changanacherry IPC Changanachery Bahsi Sedpur, Nr. T.V Joseph, JFMC 1st, Sudhakar Mujafer Jn., Karidpur Nr. Railway 29.4.17 7 849/17 U/s. Addl. SI of 5 Renjankumar 18/17 CHRY Changanacher Seni, P.O, Bassali District, Station PM 457, 380 IPC Police, y Bihar State Changanachery Palakottal, 24.04.17, 437/17 U/s Thrickodithan P.N. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Rta Kottayam Held on 03/11/2018

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE RTA KOTTAYAM HELD ON 03/11/2018. Present Chairman Dr. B.S. Thirumeni, IAS, The District Collector, Kottayam. Member Sri. Shaji Joseph, Deputy Transport Commissioner, Central Zone II, Ernakulam. Item No.01 Heard the learned counsel represented the applicant and KSRTC. This is an application for the grant fresh regular permit in respect of SC KL 05 Y 5099 / another suitable vehicle to operate on the route PALA KOTTARAMATTAM BUS STAND – PAMPADY via, Pala Old Bus Stand, 12th Mile, Panthathala, Mevida, Kanjiramattom, Chengalam, Kavungumpalam, Anickadu Pally, Pallickathodu, and Kooropada as Ordinary Service. This authority considered the application and connected documents in detail. The route portion of 1.5 kilo meter at Pala Town objectionably overlaps on Kottayam – Kattappana Scheme and a distance of 100 meters in Pampady objectionably overlaps on Ernakulam – Thekkady notified Scheme vide GO[P] No 42/2009 Trans dtd 14/07/2009, which is further modified by GO[P] No 08/2017/Tran dtd 23/03/2017. The total distance of overlapping in the proposed route is 1.6 KM ie, 4.7 % of the total route length of 34 km. These overlapping come under the permissible limit as per GO(P) No. 8/2017 Trans dated 23/03/2017. Hence this authority is in view that there is no legal impediment to grant the permit. The date of registration of the offered vehicle KL 05 Y 5099 is 08/02/2008 hence not fit for the issue of fresh regular permit as specified in the decision of STA held on 14/06/2017 in Departmental item No. -

Till 2001 - Education

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC Till 2011 - Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 1 010100031 Muhammed A Anaparakkal House,Pannicode,Pannicode 0 M M R Auto Rickshaw Transport Sector 50000 45000 01/07/1995 1 2 010100147 Rajendra Babu M S Sivananda Vilasam,Trivandrum,Mullur 0 C M R Electrical Goods Servicing Unit Service Sector 28421 25579 29/07/1995 1 010100147 Rajendra Babu M S Sivananda Vilasam,Trivandrum,Mullur 0 C M R Electrical Goods Servicing Unit Service Sector 6579 5921 26/09/1995 2 3 010100412 Sailesh Ea Edakkadu,Moolamattom,Moolamattom 0 M M R Eletrical Goods Service Service Sector 28421 25579 25/08/1995 1 010100412 Sailesh Ea Edakkadu,Moolamattom,Moolamattom 0 M M R Eletrical Goods Service Service Sector 6579 5921 31/10/1995 2 4 010100477 Chandrasekharan T Thavakkara House,Kannur,Kattampally 0 C M R Electrical Goods Servicing Service Sector 28421 25579 30/08/1995 1 010100477 Chandrasekharan T Thavakkara House,Kannur,Kattampally 0 C M R Electrical Goods Servicing Service Sector 6579 5921 08/12/1995 2 5 010100521 Kajahussain A Polani House,Puthunagaram,Pudunagaram 0 M M R Ready Made Garments Business Sector 29684 26716 18/09/1995 1 010100521 Kajahussain A Polani House,Puthunagaram,Pudunagaram 0 M M R Ready Made Garments Business Sector 12316 11084 06/12/1995 2 6 010100537 Sreekumar Pk Anitha Bhavan,Kadavanthara,Kadavanthara 0 C M U Electrical Goods And -

History-. of ··:Kerala: - • - ' - - ..>

HISTORY-. OF ··:KERALA: - • - ' - - ..> - K~ P. PAD!rlANABHA .MENON.. Rs. 8. 18 sh. ~~~~~~ .f-?2> ~ f! P~~-'1 IY~on-: f. L~J-... IYt;;_._dh, 4>.,1.9 .£,). c~c~;r.~, ~'").-)t...q_ A..Ja:..:..-. THE L ATE lVIn. K. P . PADJVIANABHA MENON. F rontispiece.] HISTORY· op::KERALA. .. :. ' ~ ' . Oowright and right of t'fanslation:. resen;e~ witk ' Mrs. K. P. PADMANABHA MENON. Copies can be had of . '. Mrs. K. P. PAI>MANABHA MENON, Sri Padmanabhalayam Bungalow~, Diwans' Road;-!Jmakulam, eochin state, S.INDIA. HISTORY OF KERALA. A HISTORY OF KERALA. WBI'l!TEN, IN THE FOBH OF NOTES ON VISSCHER'S LETTERS FROM MALABAR, BY K. P. PADMANABHA MENON, B.A., S.L, M.~.A.S., ' . Author of the History of Codzin, anti of severai P~p~rsconnectedwith the early History of Kerala; Jiak•l of the H1g-k Courts of Madras 0,.. of Travam:ore and of tke Ckief Court of. Cochin, ~ . • r . AND .EDITED BY SAHITHYAKUSALAN. "T. :K.' KRISHNA MENON, B. A.;~. • ' "'•.t . fl' Formerly, a Member of Jhe Royal Asiatic Society, and of the ~ocieties of Arts and of Aut/tors, 'anti a Fellow of the .Royal Histor~cal .Soci'ety. Kun.kamhu NamfJiyar Pr~sd:ian. For some ti'me, anE:cami'n.er for .Malayalam to the Umverfities of Madras, Benares and Hydera bad. A Member (Jf the .Board of Stzediet for Malayalam. A fJUOndum Editor of Pid,.a Vinodini. A co-Editor of tke ., .Sciene~ Primers Seriu in Malayalam. Editor of .Books for Malabar Bairns: The Author &- Editor of several works in Malayalam. A Member of the, Indian Women's Uni'r,ersity, and · · a .Sadasya of Visvn-.Bharatki, &-c. -

Kuttanad Report.Pdf

Measures to Mitigate Agrarian Distress in Alappuzha and Kuttanad Wetland Ecosystem A Study Report by M. S. SWAMINATHAN RESEARCH FOUNDATION 2007 M. S. SWAMINATHAN RESEARCH FOUNDATION FOREWORD Every calamity presents opportunities for progress provided we learn appropriate lessons from the calamity and apply effective remedies to prevent its recurrence. The Alappuzha district along with Kuttanad region has been chosen by the Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India for special consideration in view of the prevailing agrarian distress. In spite of its natural wealth, the district has a high proportion of population living in poverty. The M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation was invited by the Union Ministry of Agriculture to go into the economic and ecological problems of the Alappuzha district as well as the Kuttanad Wetland Ecosystem as a whole. The present report is the result of the study undertaken in response to the request of the Union Ministry of Agriculture. The study team was headed by Dr. S. Bala Ravi, Advisor of MSSRF with Drs. Sudha Nair, Anil Kumar and Ms. Deepa Varma as members. The Team was supported by a panel of eminent technical advisors. Recognising that the process of preparation of such reports is as important as the product, the MSSRF team held wide ranging consultations with all concerned with the economy, ecological security and livelihood security of Kuttanad wetlands. Information on the consultations held and visits made are given in the report. The report contains a malady-remedy analysis of the problems and potential solutions. The greatest challenge in dealing with multidimensional problems in our country is our inability to generate the necessary synergy and convergence among the numerous government, non-government, civil society and other agencies involved in the implementation of the programmes such as those outlined in this report.