Unit 1 Canon-Making in the Era of Gandhi, Nehru, Socialism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandhi and Socialism

International Journal of Advanced Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4030 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.24 www.advancedjournal.com Volume 2; Issue 5; September 2017; Page No. 399-401 Gandhi and socialism Dr. Neelam Pandey Assistant Professor, Dept. of Political Science & Public Administration, Annamalai University, Tamil Nadu, India Abstract Gandhi was not interested in developing any systematic theory. He believed in action. He expressed his views on socialism, which are suitable to Indian condition and environment. He has developed an Indian version of socialism, which is based on Indian philosophy. His socialism is for Indian population. In this research article a true sprit of Gandhi is socialism has been highlighted. Keywords: personality, selfishness, brotherhood, dharma, god Introduction and the vast literature of the Indian saints, and the lives of Gandhi has not written any technically sound and remarkable. these saints are the original, primeval source of socialism. Significant books on socialism. But no one can deny the fact These sources are universal, catholic, cosmic in their that he has something original, deep, significant and character, and they are concerned with the weal, welfare, contextually as well as eternally relevant to say on socialism. peace, happiness of everyone in the world. These essence of His thoughts on socialism are scattered in his numerous Bhagavad Gita is said to be ‘Saamayayoga’ which is a far writing and speeches. In this research paper a serious effort higher idea than socialism or ‘Samyavad’ [2]. All these are the has been made to find Gandhi’s views on socialism and to see sources of Gandhian socialist thought. -

Ms Nabilam Gandhianeconomi

M.K.Gandhi was born on Oct 2, 1869, @ Porbander From 1893 to 1914 Gandhi rendered great service to the cause of racial equality in South Africa. His philosophy of passive resistence, as it was known then, against the unjust persecution of the Indians in South Africa won the hearts even of his opponents He served the people of South Africa for two decades and came back to India in 1915. In 1920 Gandhi started the non-cooperation movement. In 1930 he led the ‘salt satyagraha’( Dandi march) In 1919, he conducted the civil disobedience movement and 1942 he launched the Quit India movement On 30 January 1948 he was shot dead by an Indian, named Nathu Ram Godse ,who did not agree with his views on political matters HIS ECONOMIC IDEAS Gandhi did not believe in any definite scheme of economics thought. His economic ideas are found scattered all over his writings and speeches. To him,economics was a part of way of life and hence his economic ideas are part of his general philosophy of life Gandhi’s economic ideas are based on 4 cardinal principles: truth , nonviolence, dignity of labour, and simplicity. Gandhi said that the only means of attaining eternal happiness is to lead a simple life. He believed in the principle of ‘simple living and high thinking’ He was an apostle of non-violence, and his economics may be called as economics of non-violence. The principle of non-violence is the soul of Gandhian philosophy. He believed that violence in any form will not bring any kind of peace because it breeds greater violence. -

From Marxism to Total Revolution and the Leadership Role of Loknayak Jaya Prakash Narayan: a Study

Vol-6 Issue-3 2020 IJARIIE-ISSN(O)-2395-4396 From Marxism to Total Revolution and the leadership role of Loknayak Jaya Prakash Narayan: A study Paritosh Barman Assistant Professor& Ph.D. Scholar Department of Political Science Cooch Behar Panchanan Barma University West Bengal, India Abstract JP never compromised people's interest with any ‘ism’ in his life. Jayprakash was an active supporter of the Sarvodaya Movement started by Gandhiji and spearheaded by Vinobha Bhave after Independence. JP’s Sarvodaya meant a new order to set up a classless and stateless society for the people’s socialism in the fifties. To eradicate the dominant party politics, he proposed the concept of partyless democracy and communitarian democracy to develop democratic values and culture. He devoted himself to establish people’s democracy eliminating power politics. Sampurna Kranti or total revolution was the last intellectual contribution of Jayprakash in his unending quest to seek and set up such a socio-economic and political order in the country which would turn India into a democratic, participatory, prosperous nation in the world. This study will focus on the social, political contributions of JP after Independence. He devoted himself to purify the political, socio- economic and moral aspects of the country and to the welfare of all. Keywords: Sarvodaya, Socialism, partyless democracy, non-violence, Total Revolution. I. Introduction: Loknayak Jayprakash Narayan (JP) was a freedom fighter and a social reformer. Jayprakash, who was dedicated himself to free the nation and never wanted any power or position for himself. JP always wanted to serve people as much as he could. -

Communism and Religion in North India, 1920–47

"To the Masses." Communism and Religion in North India, 1920–47 Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) eingereicht an der Kultur-, Sozial- und Bildungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin von Patrick Hesse Präsident der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Prof. Dr. Jan-Hendrik Olbertz Dekanin der Kultur-, Sozial- und Bildungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät Prof. Dr. Julia von Blumenthal Gutachter: 1. Michael Mann 2. Dietrich Reetz Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 20. Juli 2015 Abstract Among the eldest of its kind in Asia, the Communist Party of India (CPI) pioneered the spread of Marxist politics beyond the European arena. Influenced by both Soviet revolutionary practice and radical nationalism in British India, it operated under conditions not provided for in Marxist theory—foremost the prominence of religion and community in social and political life. The thesis analyzes, first, the theoretical and organizational ‘overhead’ of the CPI in terms of the position of religion in a party communist hierarchy of emancipation. It will therefore question the works of Marx, Engels, and Lenin on the one hand, and Comintern doctrines on the other. Secondly, it scrutinizes the approaches and strategies of the CPI and individual members, often biographically biased, to come to grips with the subcontinental environment under the primacy of mass politics. Thirdly, I discuss communist vistas on revolution on concrete instances including (but not limited to) the Gandhian non-cooperation movement, the Moplah rebellion, the subcontinental proletariat, the problem of communalism, and assertion of minority identities. I argue that the CPI established a pattern of vacillation between qualified rejection and conditional appropriation of religion that loosely constituted two diverging revolutionary paradigms characterizing communist practice from the Soviet outset: Western and Eastern. -

Smelws LOWER SHAW FARM Autumn/Winter Programme of Weekends: 5 — 7 Oct: Rough'woodwork — Creative Carpentry

Smelws LOWER SHAW FARM Autumn/Winter programme of weekends: 5 — 7 Oct: Rough'Woodwork — Creative Carpentry. 19 ~ 21 Oct: 34 Cowley Road, Oxford — - Walking Weekend. 7 9 Dec: Peace OX4iHZ — Tel: 0865-245301 Weekend. 4 6 Jan: Winter Cele— bration. £25 with concessions available. Wholefood meals. Send //M s.a.e to Lower Shaw Farm, Shaw, GREEN LINE is part of the \\\\\\ii‘l near Swindon, Wilts; or tel. international green movement. EWDEHOUSING CO—OP would like 0793 771080. It reflects the concerns of the to hear from people interested in alternative consensus which is living and working together in a COMMUNES NETWORK magazine is 'rejecting most of the norms of éhi rural setting near Oxford. All produced by and for people — capitalist industrial society ages welcome. For more informa— involved — or just interested as well as the established tion please write to us c/o in living and working collectively. 10 issues, 50p for 1, ideologies of right, left and Ferry House, Meadow Lane, Oxford Costs £5 per ‘ centre. The greens are far from OX4 4BJ or telephone 0865 249168: For further information send SAE exclusive: greenness is a per- to: Communes Network, c/o Some RESIDENTS WANTED for performing spective rather than an ideology. People in Leicester, 89 Evington arts/crafts community; goats, Anarchists, socialists, pagans, Road, Leicester LE2 10H. - poultry, large garden near Christians, feminists, gays, Swindon. Excellent environment RECON NEWSLETTER, contact magazine punks, hippies, vegans and so ‘ and fellow “wk.“ for children. vegetarian, non- for Buddhist ecologists on all rub shoulders. travellers. Two 1st class stamps il- smoking peace activists preferred. -

Mahatma Gandhi and His Philosophical Thoughts About Socialism: a Theoretical Discussion

Tamralipta Mahavidyalaya Research Review A Peer Reviewed National Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Online ISSN : 2456-1681 Vol.2:2017 MAHATMA GANDHI AND HIS PHILOSOPHICAL THOUGHTS ABOUT SOCIALISM: A THEORETICAL DISCUSSION Ratna Panda Dept. of Philosophy, Bajkul Milani Mahavidyalaya Bajkul, Purba Medinipur, West Bengal, India [email protected] Abstract: According to Gandhi ―Socialism is a beautiful word and so far as I am aware in socialism all the members of society are equal — none low, none high. In the individual body, the head is not high because it is the top of the body, nor are the soles of the feet low because they touch the earth. Even as members of the individual body are equal, so are the members of society‖. Socialism indicates a economic system of Society. A socialist economic system would consist of a system of production and distribution organized to directly satisfy economic demand and human needs. So that goods and service would be produces directly for use instead of private profit. Mahatma Gandhi wrote, ―Khadi is the only alternative to this and not the so-called socialism, which presupposes industrialism. The socialism that India can assimilate is the socialism of the spinning-wheel. Let the village worker; therefore, make the wheel the central point of his activities.‖ Gandhi‘s socialism may differ from western socialism. Gandhi‘s socialism mainly based on non-violence, faith on God, pure democracy, dharma and on the harmonious co-operation of labour and capital and the landlord and the tenant. In this study we try to understand the actual meaning of Gandhian socialism. -

International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research

International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research ISSN: 2455-8834 Volume: 05, Issue: 02 "February 2020" SARVODAYA IN ACTION AFTER MAHATMA GANDHI BY ACHARYA VINOBA BHAVE IN POST-INDEPENDENCE INDIA: AN ANALYTICAL STUDY Paritosh Barman Asst. Professor (Political Science), Cooch Behar Panchanan Barma University, Vivekananda Street, Cooch Behar (W.B), India. DOI: 10.46609/IJSSER.2020.v05i02.005 URL: https://doi.org/10.46609/IJSSER.2020.v05i02.005 ABSTRACT Vinayak Narahari Bhave, popularly known as ‘Acharya Vinoba Bhave’ was a saint, moral tribune, a man of God and solace to millions of Indians. Vinoba Bhave describes ‘Sarvoday’ (Universal wellbeing) as the best religion. In reality, all the religions of the World propose well- being, prosperity and happiness of all. Thus ‘Sarvodaya’ incorporates all the religions of the World. Sarvodaya Movement means a way to make an ideal society with truth, love and non- violence. The concept of Sarvodaya was first advocated by Gandhiji as the title of his Gujrati translation of John Ruskin’s “Unto this Last”. Today, Sarvodaya has become a synonym for Gandhian thought. The literary meaning of Sarvodaya is the welfare of all. Sarvodaya is an ideal as well as a movement to uplift all. It is considered as an Indian solution to World problems, Gandhian panacea for socio-economic evils. As the ardent follower of Gandhi, Vinoba Bhave started to practice Sarvodaya in action for making a Sarvodaya Society in India. To make the Indian Nation based on equality, justice and freedom for all, Vinoba launched Bhoodan, Gramdan, Sampattidan Movements to help landless poor and JP left Socialist Party to support Vinoba’s movement in 1954. -

The Political Economy of Hindu Nationalism: from V.D. Savarkar to Narendra Modi

Munich Personal RePEc Archive The Political Economy of Hindu Nationalism: From V.D. Savarkar to Narendra Modi Iwanek, Krzysztof Hankuk University of Foreign Studies 1 December 2014 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/63776/ MPRA Paper No. 63776, posted 24 Apr 2015 12:40 UTC 1 International Journal of Knowledge and Innovation in Business ISSN: 2332-3388 (print) December, 2014, Volume 2, Number 1, pp.1-38 2332-3396 (online) The Political Economy of Hindu Nationalism: From V.D. Savarkar to Narendra Modi Krzysztof Iwanek* Abstract In May 2014 India’s stock markets climbed to a record high, anticipating the victory of the Bharatiya Janata Party and its charismatic leader, Narendra Modi. However, the first economic decisions of Modi’s government did not incite a market revolution (though it has only been few months since its inception). This, however, is not surprising if one traces the Hindu nationalists’ changing views on economy throughout the last decades. The main inspirations of BJP’s ideology have been its mother-organization (RSS), and two earlier Hindu nationalist parties: Bharatiya Jana Sangh and Hindu Mahasabha (mostly through ideas of its leader, V.D. Savarkar). After briefly describing the views of all of these bodies, I will map out the main issues in the Hindu nationalist approach towards economy. Finally, I will try to show how the present government of Narendra Modi is trying to deal with these discrepancies. Keywords: political economy in India, Hindu nationalism, Hindutva, swadeshi, Bharatiya Janata Party, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh Acknowledgements This work was supported by Hankuk University of Foreign Studies Research Fund of 2014. -

Marxism and Beyond in Indian Political Thought: J

MARXISM AND BEYOND IN INDIAN POLITICAL THOUGHT: J. P. NARAYAN AND M. N. ROYfS CONCEPTS OF RADICAL DEMOCRACY Submitted by Eva-Maria Nag For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2003 1 UMI Number: U183143 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U183143 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F S20<? lot 5 7 3 S Abstract This project aims at a re-interpretation of the work of two Indian political thinkers and activists - M. N. Roy (1887-1954) and J. P. Narayan (1902-1979). In light of their early affiliation with and later rejection of communism, Marxism and nationalism, they have often been reduced to representing an idealistic anti-Marxist strand of the Indian left of the immediate pre-independence and post-independence era. However, their case for radical democracy can and should be revised. Not only does their work run parallel to some important trends within the history of the European left and thus contributes to the history of left thinking in the early to mid 20th century, it may also have a lasting impact. -

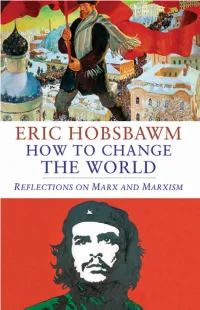

How to Change the World Also by Eric Hobsbawm

How to Change the World Also by Eric Hobsbawm The Age of Revolution 1789–1848 The Age of Capital 1848–1875 The Age of Empire 1875–1914 The Age of Extremes 1914–1991 Labouring Men Industry and Empire Bandits Revolutionaries Worlds of Labour Nations and Nationalism Since 1780 On History Uncommon People The New Century Globalisation, Democracy and Terrorism Interesting Times How to Change the World Reflections on Marx and Marxism Eric Hobsbawm New Haven & London To the memory of George Lichtheim This collection first published 2011 in the United States by Yale University Press and in Great Britain by Little, Brown. Copyright © 2011 by Eric Hobsbawm. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U.S. office) or [email protected] (U.K. office). Typeset in Baskerville by M Rules. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Control Number: 2011927314 ISBN 978-0-300-17616-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Foreword vii PART I: MARX AND ENGELS 1 Marx Today 3 2 Marx, -

Ideas of Democratic Socialism in Indian Political System

Vol. 8(3), pp. 77-81, March 2020 DOI: 10.14662/IJPSD2020.025 International Journal of Copy©right 2020 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Political Science and ISSN: 2360-784X http://www.academicresearchjournals.org/IJPSD/Index.html Development Review IDEAS OF DEMOCRATIC SOCIALISM IN INDIAN POLITICAL SYSTEM Dr. Shiw Balak Prasad Professor and Ex-Head, University Department of Political Science, B.N. Mandal University, Madhepura (Bihar), INDIA. E-mail: [email protected] Accepted 21 March 2020 Socialist thought in India, in the present century is the result of three streams of Socialist ideas. The first is the tradition of anarchistic Communitarian Socialism which was aspired by Gandhi and which is being carried forward by Vinobha Bhave in the form of Bhoodan movement and by J.P. Narain in the concept of Communitarian Society. Gandhian concept of a Ramrajya is a stateless Society, based on truth, love and non-violence. It literally means the rule of righteousness as Rama to Gandhi means ‘Truth’. This kind of Gandhian Socialism could not suit Indian conditions nor could it be found feasible for any programme of rapid economic growth. It was more utopian than practicable, more idealistic than actual. The failure of Gandhian Socialism to grapple with the needs of the country helped in the emergence of the Second Stream – that of Communism. The surging success of the Russian revolution of 1917, crossed the borders of Russia and its echoes reached India as well. The anti-imperialist aspect of Communism could well fit in the Indian freedom struggle. It captured the imagination of the people, and the leaders of the Congress. -

International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research

International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research ISSN: 2455-8834 Volume: 05, Issue: 03 "March 2020" A JOURNEY FROM SOCIALISM TO TOTAL REVOLUTION: AN EVALUATIVE STUDY OF LOKNAYAK JAYPRAKASH NARAYAN Paritosh Barman Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Cooch Behar Panchanan Barma University, Cooch Behar, West Bengal – 736101, India DOI: 10.46609/IJSSER.2020.v05i03.016 URL: https://doi.org/10.46609/IJSSER.2020.v05i03.016 ABSTRACT Loknayak Jayprakash Narayan popularly known as JP was a freedom fighter, political reformer and active political leader throughout his life. Jayprakash was educated at universities in the United States, where he became a Marxist Devotee. Upon his return to India, he joined the Indian National Congress. In the Post-Independence period, he left the party to work relentlessly the creation of an Anti-Congress Platform in 1948. By forming the Praja Socialist Party, J.P. gave voice to the marginalized and offered an alternative political platform in 1952. He tried his best to implement the Sarvodaya Movement, founded by Acharaya Vinoba Bhave. Jayprakash was an active worker of the Sarvodaya Movement started by Gandhiji and spearheaded by Vinobha Bhave. JP’s Sarvodaya meant a new order to set up a classless and stateless society for the people’s socialism in the fifties. He was deeply disturbed by the growth of political corruption in India. He was first “JeevanDanee”(devoted life) to Jeevandan Movement led by Vinoba Bhave. To eradicate the dominant party politics he proposed the concept of partyless democracy and communitarian democracy to develop democratic values and culture. Sampurna Kranti or total revolution was the last intellectual contribution of Jayprakash in his unending quest to seek and set up such a socio-economic and political order in the country which would turn India into a democratic, participatory, prosperous nation in the world.