Able Constitution and It Was Ad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Day of Sir John Macdonald – a Chronicle of the First Prime Minister

.. CHRONICLES OF CANADA Edited by George M. Wrong and H. H. Langton In thirty-two volumes 29 THE DAY OF SIR JOHN MACDONALD BY SIR JOSEPH POPE Part VIII The Growth of Nationality SIR JOHX LIACDONALD CROSSING L LALROLAILJ 3VER TIIE XEWLY COSSTRUC CANADI-IN P-ICIFIC RAILWAY, 1886 From a colour drawinrr bv C. \TT. Tefferv! THE DAY OF SIR JOHN MACDONALD A Chronicle of the First Prime Minister of the Dominion BY SIR JOSEPH POPE K. C. M. G. TORONTO GLASGOW, BROOK & COMPANY 1915 PREFATORY NOTE WITHINa short time will be celebrated the centenary of the birth of the great statesman who, half a century ago, laid the foundations and, for almost twenty years, guided the destinies of the Dominion of Canada. Nearly a like period has elapsed since the author's Memoirs of Sir John Macdonald was published. That work, appearing as it did little more than three years after his death, was necessarily subject to many limitations and restrictions. As a connected story it did not profess to come down later than the year 1873, nor has the time yet arrived for its continuation and completion on the same lines. That task is probably reserved for other and freer hands than mine. At the same time, it seems desirable that, as Sir John Macdonald's centenary approaches, there should be available, in convenient form, a short r6sum6 of the salient features of his vii viii SIR JOHN MACDONALD career, which, without going deeply and at length into all the public questions of his time, should present a familiar account of the man and his work as a whole, as well as, in a lesser degree, of those with whom he was intimately associated. -

The Rebellion of 1837 in Lower Canada

This drawing shows a group of men marching down Yonge Street, Toronto, in December 1837. What do you think these people might do when they get to where they are going? istorians study how peop le and societies have changed over time. They observe that Hconflict between people and groups occurs frequently, and that conflict is one thing that causes "t Ex eet tions change. In this unit, you will read about various This unit will expl ore the qu estion, types of conflict, ways of dealing with conflict in the How have the Canadas changed since past and in the present, and some changes that the mid-1800s? have resulted from conflict. What You Will Learn in This Unit • How do ch ange, conflict , and conflict resolution help shape history? • Why were the 1837- 1838 re be llions in Upper an d Lower Canada important? • What led to t he political un ion of t he two Ca nadas? • What were the steps to responsible govern ment in t he colonies? • How can I communicate key characteristics of British North America in 18507 RCADING e all encounter conflict from time to time. It may be personal conflict with a family member or a friend. Or Making Connections W it may be a larger conflict in the world that we hear Use rapid writing to write about on the news. Conflict appears to be something we should about a time you had a conflict expect and be able to deal with. or problem with someone. (Do There are five common reactions to conflict. -

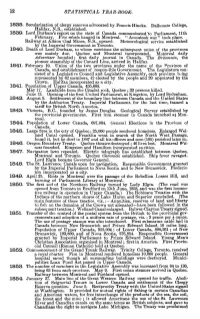

STATISTICAL YEAR-BOOK-. 1838. Secularization of Clergy Reserves

12 STATISTICAL YEAR-BOOK-. 1838. Secularization of clergy reserves advocated by Francis Hincks. Dalhousie College, Halifax, N.S., established. 1839. Lord Durham's report on the state of Canada communicated 'to Parliament, 11th February. Five rebels hanged in Montreal. " Aroostook war " took place. Railway at Albion Coal Mines, N.S., opened. Meteorological service established by the Imperial Government in Toronto. 1840. Death of Lord Durham, to whose exertions the subsequent union of the provinces was mainly due. Quebec and Montreal incorporated. Montreal daily Advertiser founded; first daily journal in Canada. The Britannia, the pioneer steamship of the Cunard Line, arrived in Halifax. 1841. February 10. Union of the two provinces under the name of the "Province of Canada, and establishment of responsible Government. The Legislature con sisted of a Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly, each province bfing represented by 62 members, 42 elected by the people and 20 appointed by the Crown. Halifax incorporated as a city. 1841. Population of Upper Canada, 455,688. May 17. Landslide from the Citadel rock, Quebec ; 32 persons killed. June 13. Opening of the first United Parliament, at Kingston, by Lord Sydenham. 1842. August 9. Settlement of the boundary line between Canada and the United States by the Ashburton Treaty. Imperial Parliament, for the last time, framed a tariff for British North America. 1843. Victoria, B.C., founded by James Douglas. Geological Survey established by the provincial government. First iron steamer in Canada launched a$ Mon treal. 1844. Population of Lower Canada, 697,084. General Elections in the Province of Canada. 1845. Large fires in the city of Quebec; 25,000 people rendered homeless. -

The Political History of Canada Between 1840 and 1855

IGtbranj KINGSTON. ONTARIO : 1 L THE POLITICAL HISTORY OF CUM BETWEEN 1840 AND 1855. A^ LECTURE DELIVERED ON THE 1 7th OCTOBER, 1877, AT THE REQUEST OP THE ST. PATRICK'S NATIONAL ASSOCIATION WITH COPIOUS ADDITIONS Hon. Sir FRANCIS HINCKS, P.C., K.C.M.G., C.B. JRontral DAWSON BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS. 1.877. «* ••••• ••••• •••«• • • • • • • • • • • I * • • • • • • • »•• • • • • « : THE POLITICAL HISTORY OF MAM BETWEEN 1840 AND 1855. A^ LECTURE DELIVERED ON THE 17th OCTOBER. 1877, AT THE REQUEST OF THE ST. PATRICK'S NATIONAL ASSOCIATION WITH COPIOUS ADDITIONS Hon. Sir FRANCIS HINCKS, P.C., K.C.M.G., C.B. Pontat DAWSON BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS. 1877. —A A desire having been expressed that the following lecture delivered on the 17th October, at the request of the St. Patrick's National Association—should be printed in pamphlet form, I have availed myself of the opportunity of elucidating some branches of the subjects treated of, by new matter, which could not have been introduced in the lecture, owing to its length. I have quoted largely from a pamphlet which I had printed in Jjondon in the year 1869, for private distribution, in consequence of frequent applications made to me, when the disestablishment of the Irish Church was under consideration in the House of Commons, for information as to the settlement of cognate ques- tions in Canada, and which was entitled w Religious Endowments in Canada: The Clergy Eeserve and Eectory Questions.— Chapter of Canadian History." The new matter in the pamphlet is enclosed within brackets, thus [ ]. F. HINCKS. Montreal, October, 1817. 77904 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/politicalhistoryOOhinc — The Political History of Canada. -

Conflict & Change Rebellions of 1837-38

Conflict & Change Rebellions of 1837-38 Grades 7-8 About this book: Teach the causes, personalities and consequences of rebellions of 1837-38 in Upper and Lower Canada. Students will recognize the nature of change and conflict, different ways of creating change, and methods of resolving conflicts. Information for students to examine the political, social, economic and legal changes that occurred as a result of the rebellions and their impact on the Canadas, and the future development of Canada. Seven complete lesson plans start with discussion questions to introduce the topic and continue with reading passages and follow-up worksheets. This book supports many of the fundamental concepts and learning outcomes from the curriculums for the province of Ontario, Grade 7, History, Conflict & Change. Written by Frances Stanford Revised by Lisa Solski Illustrated by Ric Ward and On The Mark Press Copyright © On The Mark Press 2013 This publication may be reproduced under licence from Access Copyright, or with the express written permission of On The Mark Press or as permitted by law. All rights are otherwise reserved, and no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, scanning, recording or otherwise, except as specifically authorized. “We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for this project.” All Rights Reserved Printed in Canada Published in Canada by: On The Mark Press 15 Dairy Avenue Napanee, Ontario K7R 1M4 www.onthemarkpress.com SSJ1-86 ISBN: 9781770788145 © On The Mark Press Conflict & Change - Rebellions of 1837-38 Contents Expectations............................................................................................................... -

Conflict and Change Its Nature and Patterns

Conflict and Change Its nature and patterns Including: Conflict : An Investigation Picture This Causes of Rebellion in Upper Canada Causes for Rebellion in Lower Canada Famous Personalities of the Rebellions Rebellion Effects - Long and Short Term Resolution of Conflict Every Day Conflict The Radical Rebel An Integrated Unit for Grade 7 Written by: The Curriculum Review Team 2005 Length of Unit: approximately: 19.5 hours July 2005 Written using the Ontario Curriculum Unit Planner 3.0 PLNR2002 Official Version Open Printed on Jul 19, 2005 at 3:00:33 PM Conflict and Change Its nature and patterns An Integrated Unit for Grade 7 Acknowledgements The developers are appreciative of the suggestions and comments from colleagues involved through the internal and external review process. Participating Lead Public School Boards: Mathematics, Grades 1-8 Grand Erie District School Board Kawartha Pine Ridge District School Board Renfrew District School Board Science and Technology, Grades 1-8 Lakehead District School Board Thames Valley District School Board York Region District School Board Social Studies, History and Geography, Grade 1-8 Renfrew District School Board Thames Valley District School Board York Region District School Board The following organizations have supported the elementary curriculum unit project through team building and leadership: The Council of Ontario Directors of Education The Ontario Curriculum Centre The Ministry of Education, Curriculum and Assessment Policy Branch An Integrated Unit for Grade 7 Written by: The Curriculum Review Team 2005 CAPB (416)325-0000 EDU Based on a unit by: A. Heath, K. Russell, C. Giese, J. Sheik, D. Gordon, C. Bray Thames Valley District School Board [email protected] This unit was written using the Curriculum Unit Planner, 1999-2002, which was developed in the province of Ontario by the Ministry of Education. -

Hincks, Sir Francis

HINCKS , Sir FRANCIS , banker, journalist, politician, and colonial administrator; b. 14 Dec. 1807 in Cork (Republic of Ireland), the youngest of nine children of the Reverend Thomas Dix Hincks and Anne Boult; m. first 29 July 1832 Martha Anne Stewart (d. 1874) of Legoniel, near Belfast (Northern Ireland), and they had five children; m. secondly 14 July 1875 Emily Louisa Delatre, widow of Robert Baldwin Sullivan*; d. 18 Aug. 1885 in Montreal, Que. Francis Hincks’s father was a Presbyterian clergyman whose interest in education and social reform led him to resign his pastorate and devote himself full time to teaching. His elder sons, of whom William* was one, became university teachers or clergymen, and it was assumed that Francis would follow in their footsteps. However, after briefly attending the Royal Belfast Academical Institution in 1823, he expressed a strong preference for a business career and was apprenticed to a Belfast shipping firm, John Martin and Company, in that year. In August 1832 Hincks and his bride of two weeks departed for York (Toronto), Upper Canada. He had visited the colony during the winter of 1830–31 while investigating business opportunities in the West Indies and the Canadas. Early in December he opened a wholesale dry goods, wine, and liquor warehouse in premises rented from William Warren Baldwin* and his son Robert*; the two families soon became close friends. Hincks’s first advertisement in the Colonial Advocate offered sherry, Spanish red wine, Holland Geneva (gin), Irish whiskey, dry goods, boots and shoes, and stationery to the general merchants of Upper Canada. -

Building a Nation

03_horizons2e_4th.qxp 3/31/09 3:43 PM Page 82 3 Building a Nation Chapter Outcomes This chapter describes society and culture in British North America, and how the colonies came together to form the Dominion of Canada. By the end of the chapter, you will • evaluate the interactions between Aboriginal peoples, colonists, and the government • describe how immigration influenced Canada’s identity • explain the development of Canada as a French and English country • analyze political, social, geographical, and economic factors that led to Confederation • compare the positions of the colonies on Confederation • explain the British North America Act in terms of the divisions of powers between the federal and provincial governments, and describe the three branches of federal government 82 03_horizons2e_4th.qxp 3/31/09 3:43 PM Page 83 Significance Patterns and Change Judgements CRITICAL Evidence INQUIRY Cause and Consequence Perspectives What were the social, eco- nomic, and geographical factors behind the struggle to unify the colonies in Confederation? Many people in the colonies of British North America were deeply divided on the issue of union. National unity and the gains that could come with it conflicted with fears of loss—loss of language, culture, identity, and freedom. These issues were especially important to those who were not members of the British ruling class. Key Terms Victorian Rebellion Losses Bill reserves federation assimilate Manifest Destiny enfranchisement coalition The image of Montreal’s Bonsecours Market shown on the infrastructure representation by opposite page was taken in 1875, less than ten years after mercantilism population Confederation. Imagine being one of the people in the constitution marketplace. -

Montréal, Capital of the United Canada a Parliament Beneath Your Feet

Montréal, Capital of the United Canada A Parliament Beneath Your Feet Why is this site important? To grasp the historic significance of this archaeological site, it is important to realize that Montréal was the country’s capital starting in 1844 and played an essential role – economically, politically and socially. The city was the metropolis of the United Province of Canada, or the United Canada, and the country’s financial centre. It was also a commercial hub, thanks to its international harbour. The Queen of England chose Montréal as the capital, and the members sat in the former St. Ann’s Market building, converted to house the Parliament, from 1844 to 1849. Montréal went on to establish itself as the birthplace of modern Canada, and its Parliament was witness to a major chapter in Canadian history. During the 1840s, significant reforms were adopted: French was recognized as one of the official languages of the state, and the Assembly won full control over the budget. Many changes took place in the administration: for example, several ministries (Public Works, Crown Land, Secretariat, etc.) were created to meet public needs, and the legal and educational systems were improved. In March 1848, the Reform party, led by Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine and Robert Baldwin, won the election and was recognized by the Governor General as a “responsible government.” This local autonomy within the British Empire was an important step in the lead-up to Canadian Confederation. The Parliament of the United Canada in Montréal saw major transformations in the Canadian political system. In 1849, a riot was sparked by the Royal sanction given to the act indemnifying victims of the 1837–1838 Rebellions. -

Responsible Government Introduction

LEARNING ACTIVITIES GUIDE Baldwin & La Fontaine: Toward Responsible Government Introduction The learning activities in this guide relate to the content of these four documentary films: 1) Collège La Cité (Ottawa) Imaginary Duality 2) University of Sudbury The Unity of a People: A Conversation on Responsible Government 3) University of Regina Baldwin and LaFontaine’s Journey to Implementing Responsible Government 4) Université de Saint-Boniface La Fontaine-Baldwin: The Reform Alliance and the Birth of a Country The learning activities are designed for high school students, although they could be adapted for students in junior high or middle school as well. They can be used in French, English, (reading, writing, oral communication) or social studies classes. The activities are divided into five parts: - Part 1: Interpretation activities (open questions, selected response questions, true or false questions) - Part 2: Games! - Part 3: Writing activities - Part 4: Oral communication activities - Part 5: Topics for research, reflection or independent study projects Teachers can choose from the various activities according to the needs of their students. The level of complexity varies, especially in parts 3, 4 and 5. Teachers are welcome to modify or adapt the activities in this guide. They can also complete the activities in any order. TABLE OF CONTENTS Documentaries… under the microscope! .................................................................... 4 Part 1 Interpretation activities ............................................................................................... -

Artisans De Notre Histoire

Lord Elgin: Voice of the People User’s Guide Audience: High school history classes Running time: 28:58 Historical Context Lord Elgin’s period of service as Governor-General of Canada (1846-1854) marked an important period in the country’s constitutional evolution. James Bruce, 8th Earl of Elgin, succeeded Lord Durham as Governor-General and shared his predecessor’s views on ministerial responsibility. He was also in agreement with the views of Colonial Secretary Earl Grey (who happened to be Elgin’s uncle). Grey had written that it was time to look for new methods of constitutional government for British North America, as that appeared to be the wish of its people — and Elgin held completely to that goal. At the same time, Elgin hoped for the formation of two political parties in Lower Canada: one conservative (or Tory) and the other reformist (or liberal), each allied with its counterpart in Upper Canada. A clear-sighted and just man, Elgin did not want to irritate Canadians of any stripe. He considered the various efforts to “denationalize” French Canadians as a misguided political mistake. Following the 1847 election, which saw the victory of a coalition of Lower Canadian Liberals and Upper Canadian Reformers, Elgin acceded to the wishes of the majority, inviting leaders Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine and Robert Baldwin to form a cabinet. At the opening of Parliament in 1849, Elgin became the first Governor-General to deliver his throne speech in both English and French — thereby simply and effectively affirming the political equality of both peoples. One of the bills presented to the House by Lafontaine during the 1849 parliamentary session inflamed old hatreds. -

The Family Historian

The Family Historian Patrick Wohler Column #34 Clues from Postage Stamps Family correspondence, if you can find it, can provide a lot of leads to people's origins, distant family members, and significant events. Often, however, the old letters have been thrown out but don't give up yet. Someone may have saved the envelopes or the stamps and, if you can find a stamp collection in the family, especially with the envelopes intact (so that you know it was sent to your ancestor) you could be in luck. The stamps, themselves, will be able to tell you the country of origin of the correspondent and a date range for the correspondence. The date of introduction for each stamp and the period in which it was used is known and published in such books as Scott's Stamp Catalogue , which may be available in your local library. If the catalogue suggests that there are variations of this stamp over time, you might want the help of a stamp collecting friend who will be able to identify your stamp more easily. The other thing to look for is the cancellation and you may want a magnifying glass for this. There may only be a partial one on the stamp but, if you have several stamps from the same correspondent, you may be able to put together the post office of origin and then you will know what town or village or part of a city these letters were mailed from. If you only knew that someone was from Germany, then finding that the bulk of their German correspondence was from Brake, gives you a place to start looking for their origins.