Piercing the Veil the Experience of Trance in Early Modern Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Precio Maketa Punk-Oi! Oi! Core 24 ¡Sorprendete!

GRUPO NOMBRE DEL MATERIAL AÑO GENERO LUGAR ID ~ Precio Maketa Punk-Oi! Oi! Core 24 ¡Sorprendete! La Opera De Los Pobres 2003 Punk Rock España 37 100% Pure British Oi! Música Punk HC Cd 1 Punk Rock, HC Varios 6 100% Pure British Oi! Música Punk HC Cd 2 Punk Rock, HC Varios 6 100% Pure British Oi! Música Punk HC Cd 1 Punk Rock, HC Varios 10 100% Pure British Oi! Música Punk HC Cd 2 Punk Rock, HC Varios 10 1ª Komunion 1ª Komunion 1991 Punk Rock Castellón 26 2 Minutos Valentin Alsina Punk Rock Argentina 1 2 Minutos Postal 97 1997 Punk Rock Argentina 1 2 Minutos Volvió la alegría vieja Punk Rock Argentina 2 2 Minutos Valentin Alsina Punk rock Argentina 12 2 Minutos 8 rolas Punk Rock Argentina 13 2 Minutos Postal ´97 1997 Punk Rock Argentina 32 2 Minutos Valentin Alsina Punk Rock Argentina 32 2 Minutos Volvio la alegria vieja 1995 Punk Rock Argentina 32 2 Minutos Dos Minutos De Advertencia 1999 Punk Rock Argentina 33 2 Minutos Novedades 1999 Punk Rock Argentina 33 2 Minutos Superocho 2004 Punk Rock Argentina 47 2Tone Club Where Going Ska Francia 37 2Tone Club Now Is The Time!! Ska Francia 37 37 hostias Cantando basjo la lluvia ácida Punk Rock Madrid, España 26 4 Skins The best of the 4 skins Punk Rock 27 4 Vientos Sentimental Rocksteady Rocksteady 23 5 Years Of Oi! Sweat & Beers! 5 Years Of Oi! Sweat & Beers! Rock 32 5MDR Stato Di Allerta 2008 Punk Rock Italia 46 7 Seconds The Crew 1984 Punk Rock, HC USA 27 7 Seconds Walk Together, Rock Together 1985 Punk Rock, HC USA 27 7 Seconds New Wind 1986 Punk Rock, HC USA 27 7 Seconds Live! One Plus One -

Altered States of Embodiment and the Social Aesthetics of Acupuncture Anderson KT* Machmer Hall University of Massachusetts-Amherst Amherst, Mass

Integrati & ve e M iv t e Anderson, Altern Integ Med 2013, 2:3 a d n i c r i e n t DOI: 10.4172/2327-5162.1000112 l e A Alternative & Integrative Medicine ISSN: 2327-5162 Review Article Open Access Altered States of Embodiment and the Social Aesthetics of Acupuncture Anderson KT* Machmer Hall University of Massachusetts-Amherst Amherst, Mass. 01003, USA Abstract Acupuncture therapy encompasses various domains of experience: from the aesthetics and atmosphere of the clinic; to the sensorial aspects of needling; to the aftereffects in terms of potential changes in health and lifestyle. In my research (conducted in Galway and Dublin Ireland) one of the prevailing reasons expressed by patients as to the appeal of acupuncture, and rationale for its continual use, was that treatments were regarded as both pleasurable and transformative. This transformation–in either an immediate-sensorial, or a long-term behavioral way–is the key focus of this paper. Interviews with patients strongly suggested that an embodied sense of transformation– experiencing unusual bodily and emotional sensations–is not only part of the appeal, but is one of the key constructs for determining the medical efficacy of acupuncture. Such embodied transformations are referred to as altered states of embodiment (ASE). Keywords: Acupuncture therapy; Altered states of embodiment are interpreted as signs of acupuncture’s efficacy. Patient determinations (ASE) of efficacy rest in part, or at least coincide, with the appealing aspects of time, attention, pleasure, bodily transformations and visual imagery. Introduction Further, these are aspects of treatment that a quantitative analysis of Three predominant themes emerged from my interviews with acupuncture efficacy would find difficult to register. -

Localisation of Visual Hallucinations

BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL 16 JULY 1977 147 of hypothermia; the duration of cardiac arrest; and the disturbances of sleep or consciousness.4 Hallucinations may be promptness and correctness of treatment. Peterson's pessi- evoked by sensory deprivation, but other factors are usually mistic report from California,8 in which all 15 near-drowned present; thus the "black-patch" delirium that may follow children who had fits, fixed dilated pupils, flaccidity, and loss cataract extraction in the elderly probably results from sensory Br Med J: first published as 10.1136/bmj.2.6080.147 on 16 July 1977. Downloaded from of pain sensation suffered severe anoxic encephalopathy, deprivation and mild senile brain changes and is more frequent may be explained by the high water temperatures there. In when hearing is also impaired.5 warm water the protective effect of hypothermia against brain Hallucinations may be due to focal lesions. Past experiences, damage would be missing. In contrast was the case described the quality of eidetic imagery, and psychodynamic "actors in Trondheim, Norway,9 in which a 5-year-old fell through influence the content of organic hallucinosis,6 and it would be ice in fresh water with an outside temperature of 10° below unwise to lean too heavily on the occurrence and nature of zero centigrade. He was in the water for 22 minutes and was hallucinosis in localising intracranial lesions. Visual hallucina- brought out apparently dead, with widely dilated pupils and tions are a relatively infrequent accompaniment oflesions ofthe bluish white skin. He was warmed up (the method was not calcarine cortex (Brodmann's area 17), which has few thalamo- described) and-despite the risks noted above-was given cortical connections; yet they may occur as a false-localising external cardiac massage without suffering ventricular symptom of frontal or subtentorial lesions. -

'Goblinlike, Fantastic: Little People and Deep Time at the Fin De Siècle

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output ’Goblinlike, fantastic: little people and deep time at the fin de siècle https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40443/ Version: Full Version Citation: Fergus, Emily (2019) ’Goblinlike, fantastic: little people and deep time at the fin de siècle. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email ‘Goblinlike, Fantastic’: Little People and Deep Time at the Fin De Siècle Emily Fergus Submitted for MPhil Degree 2019 Birkbeck, University of London 2 I, Emily Fergus, confirm that all the work contained within this thesis is entirely my own. ___________________________________________________ 3 Abstract This thesis offers a new reading of how little people were presented in both fiction and non-fiction in the latter half of the nineteenth century. After the ‘discovery’ of African pygmies in the 1860s, little people became a powerful way of imaginatively connecting to an inconceivably distant past, and the place of humans within it. Little people in fin de siècle narratives have been commonly interpreted as atavistic, stunted warnings of biological reversion. I suggest that there are other readings available: by deploying two nineteenth-century anthropological theories – E. B. Tylor’s doctrine of ‘survivals’, and euhemerism, a model proposing that the mythology surrounding fairies was based on the existence of real ‘little people’ – they can also be read as positive symbols of the tenacity of the human spirit, and as offering access to a sacred, spiritual, or magic, world. -

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

'A Great Or Notorious Liar': Katherine Harrison and Her Neighbours

‘A Great or Notorious Liar’: Katherine Harrison and her Neighbours, Wethersfield, Connecticut, 1668 – 1670 Liam Connell (University of Melbourne) Abstract: Katherine Harrison could not have personally known anyone as feared and hated in their own home town as she was in Wethersfield. This article aims to explain how and why this was so. Although documentation is scarce for many witch trials, there are some for which much crucial information has survived, and we can reconstruct reasonably detailed accounts of what went on. The trial of Katherine Harrison of Wethersfield, Connecticut, at the end of the 1660s is one such case. An array of factors coalesced at the right time in Wethersfield for Katherine to be accused. Her self-proclaimed magical abilities, her socio- economic background, and most of all, the inter-personal and legal conflicts that she sustained with her neighbours all combined to propel this woman into a very public discussion about witchcraft in 1668-1670. The trial of Katherine Harrison was a vital moment in the development of the legal and theological responses to witchcraft in colonial New England. The outcome was the result of a lengthy process jointly negotiated between legal and religious authorities. This was the earliest documented case in which New England magistrates trying witchcraft sought and received explicit instruction from Puritan ministers on the validity of spectral evidence and the interface between folk magic and witchcraft – implications that still resonated at the more recognised Salem witch trials almost twenty-five years later. The case also reveals the social dynamics that caused much ambiguity and confusion in this early modern village about an acceptable use of the occult. -

On Fairy Stories by J

On Fairy Stories By J. R. R. Tolkien On Fairy-stories This essay was originally intended to be one of the Andrew Lang lectures at St. Andrews, and it was, in abbreviated form, delivered there in 1938. To be invited to lecture in St. Andrews is a high compliment to any man; to be allowed to speak about fairy-stories is (for an Englishman in Scotland) a perilous honor. I felt like a conjuror who finds himself, by mistake, called upon to give a display of magic before the court of an elf-king. After producing his rabbit, such a clumsy performer may consider himself lucky, if he is allowed to go home in proper shape, or indeed to go home at all. There are dungeons in fairyland for the overbold. And overbold I fear I may be accounted, because I am a reader and lover of fairy-stories, but not a student of them, as Andrew Lang was. I have not the learning, nor the still more necessary wisdom, which the subject demands. The land of fairy-story is wide and deep and high, and is filled with many things: all manner of beasts and birds are found there; shoreless seas and stars uncounted; beauty that is an enchantment, and an ever-present peril; both sorrow and joy as sharp as swords. In that land a man may (perhaps) count himself fortunate to have wandered, but its very riches and strangeness make dumb the traveller who would report it. And while he is there it is dangerous for him to ask too many questions, lest the gates shut and the keys be lost. -

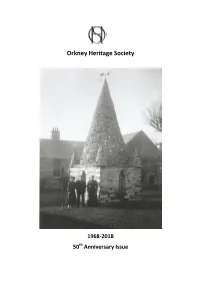

2018 50Th Anniversary Issue

Orkney Heritage Society 1968-2018 50th Anniversary Issue Objectives of the Orkney Heritage Society The aims of the Society are to promote and encourage the following objectives by charitable means: 1. To stimulate public interest in, and care for the beauty, history and character of Orkney. 2. To encourage the preservation, development and improvement of features of general public amenity or historical interest. 3. To encourage high standards of architecture and town planning in Orkney. 4. To pursue these ends by means of meetings, exhibitions, lectures, conferences, publicity and promotion of schemes of a charitable nature. New members are always welcome To learn more about the society and its ongoing work, check out the regularly updated website at www.orkneycommunities.co.uk/ohs or contact us at Orkney Heritage Society PO Box No. 6220 Kirkwall Orkney KW15 9AD Front Cover: Robert Garden and his wife, Margaret Jolly, along with one of their daughters standing next to the newly re-built Groatie Hoose. It got its name from the many shells, including ‘groatie buckies’, decorating the tower. Note the weather vane showing some of Garden’s floating shops. Photo gifted by Mrs Catherine Dinnie, granddaughter of Robert Garden. 1 Orkney Heritage Society Committee 2018 President: Sandy Firth, Edan, Berstane Road, Kirkwall, KW15 1NA [email protected] Vice President: Sheena Wenham, Withacot, Holm [email protected] Chairman: Spencer Rosie, 7 Park Loan, Kirkwall, KW15 1PU [email protected] Vice Chairman: David Murdoch, 13 -

Morgan Le Fay's Ultimate Treason Revealed

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Lehigh University: Lehigh Preserve Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 1993 Avalon revisited : Morgan le Fay's ultimate treason revealed: and 'The veils of wretched love':uncovering Sister Loepolda's hidded truths in Louise Erdrich's Love medicine and Tracks Ann Maureen Cavanaugh Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Recommended Citation Cavanaugh, Ann Maureen, "Avalon revisited : Morgan le Fay's ultimate treason revealed: and 'The eiv ls of wretched love':uncovering Sister Loepolda's hidded truths in Louise Erdrich's Love medicine and Tracks" (1993). Theses and Dissertations. Paper 201. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UH R: Cavanaugh,. nn Maureen T~TLE:, valon Revisited: Morgan La Fayus Ultimate I Treason Revealedaac ""'l DATE: October 10,1993 Avalon Revisited: Morgan Ie Fay's Ultimate Treason Revealed and 'The Veils of Wretched Love': uncovering sister Leopolda's Hidden Truths in Louise Erdrich's Love Medicine and Tracks by Ann Maureen Cavanaugh A Thesis Presented to the Graduate and Research Committee of Lehigh University in candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English Lehigh university October 1993 "Yet in every winter's heart there is a quivering spring, and behind the veil of each night there is a smiling dawn. Now my despair has turned into hope." (Kahlil Gibran) Thanks Dad, Mom, Gr~ndmom, Bert, steen, Andrea, and Maurice for your loving support. -

Changelings-High-School-Edition.Pdf

CHANGELINGS: HIGH SCHOOL PERFORMANCE EDITION Written by Reina Hardy Reinahardy.com 312-330-3031 [email protected] For whatsoever from one place doth fall, Is with the tide unto another brought: For there is nothing lost, that may be found, if sought. -The Fairy Queen, Edmond Spenser Forget about the baby. -Labyrinth, David Bowie Note: This version of the script takes place in Austin, TX, but could be adapted to any city with at least one university. ii. Casting Information Humans, in order of appearance The Young Mother- female Luther Powers- male, early 20s. Has a habit of holding eye contact with others for entirely too long. Megan Powers- His sister. Female, early 20s. Knows she is pretty. Timothy Stamp- Her fiance. Male, early 20s. Magus Kemp- any gender, but male is preferred. A grandiose and talkative wizard. Angus Powers- male, 30s-40s. A less than ideal father from the Elizabethan era. Fairies, in order of appearance (note, with the exception of the Wicked Child and Pandora, the gender casting for fairies is quite flexible. Adjust pronouns as needed.) The Wicked Child/Elizabeth- female, appears around 13. A whimsical, dangerous fairy princess with a habit of stealing babies. The Whiteling- any gender, sort of a mother of pearl gargoyle thing. The Mysterious Figure/Pandora- female. An immensely powerful and scary fairy queen. The Luck Angel- any gender. A very kind and pretty fairy. Luwis- any gender. A fairy janitor. Grunts. Bantam Beth- a little girl who is also a fierce fighter. Bantam- the same person as Bantam Beth, but a large burly dude. -

The Witch-Cult in Western Europe, by 1

The Witch-cult in Western Europe, by 1 The Witch-cult in Western Europe, by Margaret Alice Murray This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Witch-cult in Western Europe A Study in Anthropology Author: Margaret Alice Murray Release Date: January 22, 2007 [EBook #20411] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WITCH-CULT IN WESTERN EUROPE *** Produced by Michael Ciesielski, Irma Špehar and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net THE WITCH-CULT IN WESTERN EUROPE A Study in Anthropology BY MARGARET ALICE MURRAY The Witch-cult in Western Europe, by 2 OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS 1921 Oxford University Press London Edinburgh Glasgow Copenhagen New York Toronto Melbourne Cape Town Bombay Calcutta Madras Shanghai Humphrey Milford Publisher to the UNIVERSITY PREFACE The mass of existing material on this subject is so great that I have not attempted to make a survey of the whole of European 'Witchcraft', but have confined myself to an intensive study of the cult in Great Britain. In order, however, to obtain a clearer understanding of the ritual and beliefs I have had recourse to French and Flemish sources, as the cult appears to have been the same throughout Western Europe. The New England records are unfortunately not published in extenso; this is the more unfortunate as the extracts already given to the public occasionally throw light on some of the English practices. -

Episode #032 – a Deed Without a Name

“The Infinite and the Beyond” hosted by Chris Orapello Episode #032 – A Deed Without A Name 1 Episode #032 – A Deed Without A Name The Infinite and the Beyond An esoteric podcast for the introspective pagan mind hosted by Chris Orapello www.infinite-beyond.com Show Introduction. ➢ MM, BB, 93, Hello and Welcome to the 32nd Episode of “The Infinite and the Beyond,” an esoteric podcast for the introspective pagan mind. Where we explore a variety of topics which relate to life and one’s unique spiritual journey. I am your host Chris Orapello. Intro music by George Wood. ➢ In this episode… • We speak with Author, Lee Morgan about her new book A Deed Without A Name: Unearthing the Legacy of Traditional Witchcraft. We hear some awesome music by our featured artist Swallows from their latest album “Witching and Divining.” In A Corner in the Occult we learn about Scottish witch Isobel Gowdie who was tried for witchcraft back in the 17th century. And in the Essence of Magick we consider the values and issues surrounding Authenticity, but before all that, here is “Witching and Divining” by the band Swallows. Enjoy. ▪ http://swallows.bandcamp.com/album/witching-divining ▪ http://swallowthemusic.com/ Featured Artist “Witching and Diving” by Swallows Interview Part 1 : Lee Morgan Segment: A Corner in the Occult: (approx. 1300-1500 words): Isobel Gowdie (Background Music: “Piano Quartet in g 3rd Movement by Mozart” performed by Linda Holzer) Hello and welcome to “A Corner in the Occult” Where we focus on one part or person from the history of occultism.