Particle Motions Caused by Seismic Interface Waves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acoustic Particle Velocity Investigations in Aeroacoustics Synchronizing PIV and Microphone Measurements

INTER-NOISE 2016 Acoustic particle velocity investigations in aeroacoustics synchronizing PIV and microphone measurements Lars SIEGEL1; Klaus EHRENFRIED1; Arne HENNING1; Gerrit LAUENROTH1; Claus WAGNER1, 2 1 German Aerospace Center (DLR), Institute of Aerodynamics and Flow Technology (AS), Göttingen, Germany 2 Technical University Ilmenau, Institute of Thermodynamics and Fluid Mechanics, Ilmenau, Germany ABSTRACT The aim of the present study is the detection and visualization of the sound propagation process from a strong tonal sound source in flows. To achieve this, velocity measurements were conducted using particle image velocimetry (PIV) in a wind tunnel experiment under anechoic conditions. Simultaneously, the acoustic pressure fluctuations were recorded by microphones in the acoustic far field. The PIV fields of view were shifted stepwise from the source region to the vicinity of the microphones. In order to be able to trace the acoustic propagation, the cross-correlation function between the velocity and the pressure fluctuations yields a proxy variable for the acoustic particle velocity acting as a filter for the velocity fluctuations. The temporal evolution of this quantity indicates the propagation of the acoustic perturbations. The acoustic radiation of a square rod in a wind tunnel flow is investigated as a test case. It can be shown that acoustic waves propagate from emanating coherent flow structures in the near field through the shear layer of the open jet to the far field. To validate this approach, a comparison with a 2D simulation and a 2D analytical solution of a dipole is performed. 1. INTRODUCTION The localization of noise sources in turbulent flows and the traceability of the acoustic perturbations emanating from the source regions into the far field are still challenging. -

Acoustics: the Study of Sound Waves

Acoustics: the study of sound waves Sound is the phenomenon we experience when our ears are excited by vibrations in the gas that surrounds us. As an object vibrates, it sets the surrounding air in motion, sending alternating waves of compression and rarefaction radiating outward from the object. Sound information is transmitted by the amplitude and frequency of the vibrations, where amplitude is experienced as loudness and frequency as pitch. The familiar movement of an instrument string is a transverse wave, where the movement is perpendicular to the direction of travel (See Figure 1). Sound waves are longitudinal waves of compression and rarefaction in which the air molecules move back and forth parallel to the direction of wave travel centered on an average position, resulting in no net movement of the molecules. When these waves strike another object, they cause that object to vibrate by exerting a force on them. Examples of transverse waves: vibrating strings water surface waves electromagnetic waves seismic S waves Examples of longitudinal waves: waves in springs sound waves tsunami waves seismic P waves Figure 1: Transverse and longitudinal waves The forces that alternatively compress and stretch the spring are similar to the forces that propagate through the air as gas molecules bounce together. (Springs are even used to simulate reverberation, particularly in guitar amplifiers.) Air molecules are in constant motion as a result of the thermal energy we think of as heat. (Room temperature is hundreds of degrees above absolute zero, the temperature at which all motion stops.) At rest, there is an average distance between molecules although they are all actively bouncing off each other. -

Chapter 3 Wave Properties of Particles

Chapter 3 Wave Properties of Particles Overview of Chapter 3 Einstein introduced us to the particle properties of waves in 1905 (photoelectric effect). Compton scattering of x-rays by electrons (which we skipped in Chapter 2) confirmed Einstein's theories. You ought to ask "Is there a converse?" Do particles have wave properties? De Broglie postulated wave properties of particles in his thesis in 1924, based partly on the idea that if waves can behave like particles, then particles should be able to behave like waves. Werner Heisenberg and a little later Erwin Schrödinger developed theories based on the wave properties of particles. In 1927, Davisson and Germer confirmed the wave properties of particles by diffracting electrons from a nickel single crystal. 3.1 de Broglie Waves Recall that a photon has energy E=hf, momentum p=hf/c=h/, and a wavelength =h/p. De Broglie postulated that these equations also apply to particles. In particular, a particle of mass m moving with velocity v has a de Broglie wavelength of h λ = . mv where m is the relativistic mass m m = 0 . 1-v22/ c In other words, it may be necessary to use the relativistic momentum in =h/mv=h/p. In order for us to observe a particle's wave properties, the de Broglie wavelength must be comparable to something the particle interacts with; e.g. the spacing of a slit or a double slit, or the spacing between periodic arrays of atoms in crystals. The example on page 92 shows how it is "appropriate" to describe an electron in an atom by its wavelength, but not a golf ball in flight. -

Chapter 12: Physics of Ultrasound

Chapter 12: Physics of Ultrasound Slide set of 54 slides based on the Chapter authored by J.C. Lacefield of the IAEA publication (ISBN 978-92-0-131010-1): Diagnostic Radiology Physics: A Handbook for Teachers and Students Objective: To familiarize students with Physics or Ultrasound, commonly used in diagnostic imaging modality. Slide set prepared by E.Okuno (S. Paulo, Brazil, Institute of Physics of S. Paulo University) IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency Chapter 12. TABLE OF CONTENTS 12.1. Introduction 12.2. Ultrasonic Plane Waves 12.3. Ultrasonic Properties of Biological Tissue 12.4. Ultrasonic Transduction 12.5. Doppler Physics 12.6. Biological Effects of Ultrasound IAEA Diagnostic Radiology Physics: a Handbook for Teachers and Students – chapter 12,2 12.1. INTRODUCTION • Ultrasound is the most commonly used diagnostic imaging modality, accounting for approximately 25% of all imaging examinations performed worldwide nowadays • Ultrasound is an acoustic wave with frequencies greater than the maximum frequency audible to humans, which is 20 kHz IAEA Diagnostic Radiology Physics: a Handbook for Teachers and Students – chapter 12,3 12.1. INTRODUCTION • Diagnostic imaging is generally performed using ultrasound in the frequency range from 2 to 15 MHz • The choice of frequency is dictated by a trade-off between spatial resolution and penetration depth, since higher frequency waves can be focused more tightly but are attenuated more rapidly by tissue The information in an ultrasonic image is influenced by the physical processes underlying propagation, reflection and attenuation of ultrasound waves in tissue IAEA Diagnostic Radiology Physics: a Handbook for Teachers and Students – chapter 12,4 12.1. -

Sound Waves Sound Waves • Speed of Sound • Acoustic Pressure • Acoustic Impedance • Decibel Scale • Reflection of Sound Waves • Doppler Effect

In this lecture • Sound waves Sound Waves • Speed of sound • Acoustic Pressure • Acoustic Impedance • Decibel Scale • Reflection of sound waves • Doppler effect Sound Waves (Longitudinal Waves) Sound Range Frequency Source, Direction of propagation Vibrating surface Audible Range 15 – 20,000Hz Propagation Child’’s hearing 15 – 40,000Hz of zones of Male voice 100 – 1500Hz alternating ------+ + + + + compression Female voice 150 – 2500Hz and Middle C 262Hz rarefaction Concert A 440Hz Pressure Bat sounds 50,000 – 200,000Hz Wavelength, λ Medical US 2.5 - 40 MHz Propagation Speed = number of cycles per second X wavelength Max sound freq. 600 MHz c = f λ B Speed of Sound c = Sound Particle Velocity ρ • Speed at which longitudinal displacement of • Velocity, v, of the particles in the particles propagates through medium material as they oscillate to and fro • Speed governed by mechanical properties of c medium v • Stiffer materials have a greater Bulk modulus and therefore a higher speed of sound • Typically several tens of mms-1 1 Acoustic Pressure Acoustic Impedance • Pressure, p, caused by the pressure changes • Pressure, p, is applied to a molecule it induced in the material by the sound energy will exert pressure the adjacent molecule, which exerts pressure on its c adjacent molecule. P0 P • It is this sequence that causes pressure to propagate through medium. • p= P-P0 , (where P0 is normal pressure) • Typically several tens of kPa Acoustic Impedance Acoustic Impedance • Acoustic pressure increases with particle velocity, v, but also depends -

4.9. Noise and Vibration 4.9.1

City of Malibu Environmental Impact Analysis Noise and Vibration 4.9. Noise and Vibration 4.9.1. Introduction This section provides an overview of the existing noise environment as well as applicable plans and policies. It also evaluates the potential for noise impacts to occur as a result of the proposed Project. Appendix H to this draft EIR includes the relevant noise data used to analyze impacts in this analysis. The Project, which would be constructed in three phases, has four main elements that could result in noise impacts: 1) wastewater treatment facility, 2) pump stations, 3) wastewater collection and recycled water distribution system pipelines, and 4) percolation ponds and groundwater injection wells. For the purposes of this section, “Project area” refers to the area that encompasses the extents of the four main elements described above and the area that would be served by these proposed Project facilities; “Project site” refers specifically to those areas that would be disturbed by construction activities associated with these four main elements. The Project would include a Local Coastal Program Amendment and modification of zoning for the wastewater treatment facility to include an Institutional District Overlay. Noise Fundamentals Noise is generally defined as unwanted sound. It may be loud, unpleasant, unexpected, or undesired sound typically associated with human activity that interferes with or disrupts the normal noise- sensitive ongoing activities of others. The objectionable nature of noise can be caused by its pitch or its loudness. Pitch is the height or depth of a tone or sound, depending on the relative rapidity (frequency) of the vibrations by which it is produced. -

Ch 7, Vib Fundamentals

Chapter 7: Basic Ground-Borne Vibration Concepts 7-1 7. BASIC GROUND-BORNE VIBRATION CONCEPTS Ground-borne vibration can be a serious concern for nearby neighbors of a transit system route or maintenance facility, causing buildings to shake and rumbling sounds to be heard. In contrast to airborne noise, ground- borne vibration is not a common environmental problem. It is unusual for vibration from sources such as buses and trucks to be perceptible, even in locations close to major roads. Some common sources of ground- borne vibration are trains, buses on rough roads, and construction activities such as blasting, pile driving and operating heavy earth-moving equipment. The effects of ground-borne vibration include feelable movement of the building floors, rattling of windows, shaking of items on shelves or hanging on walls, and rumbling sounds. In extreme cases, the vibration can cause damage to buildings. Building damage is not a factor for normal transportation projects with the occasional exception of blasting and pile driving during construction. Annoyance from vibration often occurs when the vibration exceeds the threshold of perception by 10 decibels or less. This is an order of magnitude below the damage threshold for normal buildings. The basic concepts of ground-borne vibration are illustrated for a rail system in Figure 7-1. The train wheels rolling on the rails create vibration energy that is transmitted through the track support system into the transit structure. The amount of energy that is transmitted into the transit structure is strongly dependent on factors such as how smooth the wheels and rails are and the resonance frequencies of the vehicle suspension system and the track support system. -

Absolute Calibration of Pressure and Particle Velocity Microphones A

UIUC Physics 193POM/406POM Acoustical Physics of Music/Musical Instruments Absolute Calibration of Pressure and Particle Velocity Microphones A. Absolute Calibration of Pressure Microphones 22 The Sound Pressure Level (SPL): SPL LPrmsrms10log10 p p 0 0log 10 p p 0 ( dB ) 5 where p0 reference sound over-pressure amplitude = 2.0×10 rms Pascals = 20 rms Pa = the {average} threshold of human hearing (at f = 1 KHz). Useful conversion factor(s): p = 1.0 rms Pascal SPL = 94.0 dB (in a free-air sound field) 2 n.b. 1.0 rms Pascal = 1.0 rms Pa = 1.0 rms N/m . We can determine (i.e. measure) the absolute sensitivity of a pressure microphone e.g. in a free-air sound field – such as the great wide-open or in an anechoic room{at an industry-standard reference frequency f = 1 KHz} side-by-side with a {NIST-absolutely calibrated} SPL Meter a distance of a few meters away from a sound source – e.g. a loudspeaker. We turn up the volume of the sound source until the SPL Meter e.g. reads a steady SPL of 94.0 dB (quite loud!) which corresponds to a p = 1.0 rms Pascal acoustic over-pressure amplitude. We then measure the rms AC voltage amplitude of the output of the pressure microphone Vpmic- (in rms Volts) e.g. using a Fluke 77 DMM on RMS AC volts. Thus, the absolute sensitivity of the pressure microphone is: Spmic-- V Pa,@ f 1 KHz , SPL 94 dB V pmic rmsVolts 1.0 rms Pa n.b. -

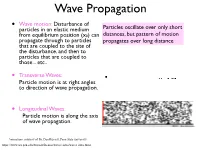

Standing Waves When They Superpose

Wave Propagation • Wave motion: Disturbance of particles in an elastic medium Particles oscillate over only short from equilibrium position (x0) can distances, but pattern of motion propagate through to particles propagates over long distance that are coupled to the site of the disturbance, and then to particles that are coupled to those... etc.. • Transverse Waves: Particle motion is at right angles to direction of wave propagation. • Longitudinal Waves: Particle motion is along the axis of wave propagation. Animations courtesy of Dr. Dan Russell, Penn State university https://www.acs.psu.edu/drussell/Demos/waves-intro/waves-intro.html Longitudinal Sound Waves Sinusoidal oscillation of air molecule positions at any given point in space results in sinusoidal oscillation of pressure between pressure maxima and minima (rarefactions). Sinusoidal oscillation in particle velocity also results--90˚ out of • phase with pressure. • Due to propagation sinusoidal pattern can also be seen in space. Increased Zero λ Velocity Decreased Velocity Velocity Wavelength (λ) is the distance in space between successive maxima (or minima) Wavelength and frequency Speed of Sound (c): • Pressure wave propagates through air at 34,029 cm/sec • Since distance traveled = velocity * elapsed time • if T is the period of one sinusoidal oscillation, then: λ = cT • And since T=1/f : λ = c/f Superposition of waves Waves traveling in opposite directions superpose when they coincide, then continue traveling. Oscillations of the same frequency, and same amplitude form standing waves when they superpose. •Don’t travel, only change in amplitude over time. •Nodes: no change in position. •Anti-nodes: maximal change in position. -

Sound Pressure and Particle Velocity Measurements from Marine Pile Driving at Eagle Harbor Maintenance Facility, Bainbridge Island WA

Suite 2101 – 4464 Markham Street Victoria, British Columbia, V8Z 7X8, Canada Phone: +1.250.483.3300 Fax: +1.250.483.3301 Email: [email protected] Website: www.jasco.com Sound pressure and particle velocity measurements from marine pile driving at Eagle Harbor maintenance facility, Bainbridge Island WA by Alex MacGillivray and Roberto Racca JASCO Research Ltd Suite 2101-4464 Markham St. Victoria, British Columbia V8Z 7X8 Canada prepared for Washington State Department of Transportation November 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction................................................................................................................. 1 2. Project description ...................................................................................................... 1 3. Experimental description ............................................................................................ 2 4. Methodology............................................................................................................... 4 4.1. Theory................................................................................................................. 4 4.2. Measurement apparatus ...................................................................................... 5 4.3. Data processing................................................................................................... 6 4.4. Acoustic metrics.................................................................................................. 7 4.4.1. Sound pressure levels................................................................................. -

Dynamics and Acceleration in Linear Structures J

DYNAMICS AND ACCELERATION IN LINEAR STRUCTURES J. Le Duff Laboratoire de l'Accélérateur Linéaire Bat. 200, Centre d'Orsay, 91405 Orsay, France 1 . BASIC METHODS OF LINEAR ACCELERATION 1 . 1 Early days In principle a linear accelerator is one in which the particles are accelerated on a linear path. Then the most simple scheme is the one which uses an electrostatic field as shown in Fig. 1. A high voltage is shared between a set of electrodes creating an electric accelerating field between them. The disadvantage of such a scheme, as far as high energies are concerned, is that all the partial accelerating voltages add up at some point and that the generation of such high electrostatic voltages will be rapidly limited (a few ten MV). This type of accelerator is however currently used for low energy ion acceleration, and is better known as the Van De Graaf accelerator. Fig. 1 Electrostatic accelerator scheme In the late 1920's propositions were made, essentially by R. Wideroe, to avoid the limitation of electrostatic devices due to voltage superposition. The proposed scheme, later on (early 1930's) improved by E. Lawrence and D. Sloan at the Berkeley University, is shown on Fig. 2. Fig. 2 Wideroe-type accelerator 82 An oscillator (7 MHz at that time) feeds alternately a series of drift tubes in such a way that particles see no field when travelling inside these tubes while they are accelerated in between. The last statement is true if the drift tube length L satisfies the synchronism condition: vT L = 2 where v is the particle velocity (βc) and T the period of the a.c. -

The Acoustic Wave Equation and Simple Solutions

Chapter 5 THE ACOUSTIC WAVE EQUATION AND SIMPLE SOLUTIONS 5.1INTRODUCTION Acoustic waves constitute one kind of pressure fluctuation that can exist in a compressible fluido In addition to the audible pressure fields of modera te intensity, the most familiar, there are also ultrasonic and infrasonic waves whose frequencies lie beyond the limits of hearing, high-intensity waves (such as those near jet engines and missiles) that may produce a sensation of pain rather than sound, nonlinear waves of still higher intensities, and shock waves generated by explosions and supersonic aircraft. lnviscid fluids exhibit fewer constraints to deformations than do solids. The restoring forces responsible for propagating a wave are the pressure changes that oc cur when the fluid is compressed or expanded. Individual elements of the fluid move back and forth in the direction of the forces, producing adjacent regions of com pression and rarefaction similar to those produced by longitudinal waves in a bar. The following terminology and symbols will be used: r = equilibrium position of a fluid element r = xx + yy + zz (5.1.1) (x, y, and z are the unit vectors in the x, y, and z directions, respectively) g = particle displacement of a fluid element from its equilibrium position (5.1.2) ü = particle velocity of a fluid element (5.1.3) p = instantaneous density at (x, y, z) po = equilibrium density at (x, y, z) s = condensation at (x, y, z) 113 114 CHAPTER 5 THE ACOUSTIC WAVE EQUATION ANO SIMPLE SOLUTIONS s = (p - pO)/ pO (5.1.4) p - PO = POS = acoustic density at (x, y, Z) i1f = instantaneous pressure at (x, y, Z) i1fO = equilibrium pressure at (x, y, Z) P = acoustic pressure at (x, y, Z) (5.1.5) c = thermodynamic speed Of sound of the fluid <I> = velocity potential of the wave ü = V<I> .