Partly Free 49 12 20 17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia's 2008 Presidential Election

Election Observation Report: Georgia’s 2008 Presidential Elections Election Observation Report: Georgia’s saarCevno sadamkvirveblo misiis saboloo angariSi angariSi saboloo misiis sadamkvirveblo saarCevno THE IN T ERN at ION A L REPUBLIC A N INS T I T U T E 2008 wlis 5 ianvari 5 wlis 2008 saqarTvelos saprezidento arCevnebi saprezidento saqarTvelos ADV A NCING DEMOCR A CY WORLD W IDE demokratiis ganviTarebisTvis mTel msoflioSi mTel ganviTarebisTvis demokratiis GEORGI A PRESIDEN T I A L ELEC T ION JA NU A RY 5, 2008 International Republican Institute saerTaSoriso respublikuri instituti respublikuri saerTaSoriso ELEC T ION OBSERV at ION MISSION FIN A L REPOR T Georgia Presidential Election January 5, 2008 Election Observation Mission Final Report The International Republican Institute 1225 Eye Street, NW, Suite 700 Washington, DC 20005 www.iri.org TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction 3 II. Pre-Election Period 5 A. Political Situation November 2007 – January 2008 B. Presidential Candidates in the January 5, 2008 Presidential Election C. Campaign Period III. Election Period 11 A. Pre-Election Meetings B. Election Day IV. Findings and Recommendations 15 V. Appendix 19 A. IRI Preliminary Statement on the Georgian Presidential Election B. Election Observation Delegation Members C. IRI in Georgia 2008 Georgia Presidential Election 3 I. Introduction The January 2008 election cycle marked the second presidential election conducted in Georgia since the Rose Revolution. This snap election was called by President Mikheil Saakashvili who made a decision to resign after a violent crackdown on opposition street protests in November 2007. Pursuant to the Georgian Constitution, he relinquished power to Speaker of Parliament Nino Burjanadze who became Acting President. -

Summons and Complaint

FILED: NEW YORK COUNTY CLERK 01/22/2010 INDEX NO. 150024/2010 NYSCEF DOC. NO. 1 RECEIVED NYSCEF: 01/22/2010 SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK JWL Group, Inc. and Joseph Kay, as Personal Representatives of the late Arcady Badri Index No. ______/10 Patarkatsishvili, Little Rest Twelve, Inc., and Fisher Island Investments, Inc., Plaintiffs, - against - Inna Gudavadze a/k/a Ina Goudavadze, Boris Berezovsky a/k/a Platon Elenin, Yuly Dubov, Anatoly Motkin, Sophie Boubnova, Victor Perelman, and John Does 1-50, Defendants. Summons and Complaint STERNIK & ZELTSER 119 West 72nd Street # 229 New York, NY 10023 t/f: 212-656-1810 email: [email protected] MOUND COTTON, WOLLAN & GREENGRASS Michael R. Koblenz, Esq. One Battery Park Plaza New York, NY 10004-1486 (2 I 2) 804-4200 SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK JWL Group, Inc. and Joseph Kay, as Personal Representatives of the late Arcady Badri Index No. ______/10 Patarkatsishvili, Little Rest Twelve, Inc., and Fisher Island Investments, Inc., Summons Plaintiffs, - against - Inna Gudavadze a/k/a Ina Goudavadze, Boris Berezovsky a/k/a Platon Elenin, Yuly Dubov, Anatoly Motkin, Sophie Boubnova, Victor Perelman, and John Does 1-50, Defendants. To the above named Defendants: YOU ARE HEREBY SUMMONED to appear in this Supreme Court of the State of New York, County of New York at 60 Centre Street in New York City within twenty (20) days of service of the Summons, exclusive of the day of service, or within thirty (30) days after the service is complete if this Summons is not personally delivered to you within the State of New York, and to answer this Summons and the allegations set forth in the annexed Complaint with the Clerk, and serve a true copy thereof upon the Attorney for Plaintiff. -

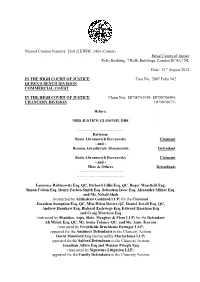

Berezovsky-Judgment.Pdf

Neutral Citation Number: [2012] EWHC 2463 (Comm) Royal Courts of Justice Rolls Building, 7 Rolls Buildings, London EC4A 1NL Date: 31st August 2012 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE Case No: 2007 Folio 942 QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION COMMERCIAL COURT IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE Claim Nos: HC08C03549; HC09C00494; CHANCERY DIVISION HC09C00711 Before: MRS JUSTICE GLOSTER, DBE - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: Boris Abramovich Berezovsky Claimant - and - Roman Arkadievich Abramovich Defendant Boris Abramovich Berezovsky Claimant - and - Hine & Others Defendants - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Laurence Rabinowitz Esq, QC, Richard Gillis Esq, QC, Roger Masefield Esq, Simon Colton Esq, Henry Forbes-Smith Esq, Sebastian Isaac Esq, Alexander Milner Esq, and Ms. Nehali Shah (instructed by Addleshaw Goddard LLP) for the Claimant Jonathan Sumption Esq, QC, Miss Helen Davies QC, Daniel Jowell Esq, QC, Andrew Henshaw Esq, Richard Eschwege Esq, Edward Harrison Esq and Craig Morrison Esq (instructed by Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP) for the Defendant Ali Malek Esq, QC, Ms. Sonia Tolaney QC, and Ms. Anne Jeavons (instructed by Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP) appeared for the Anisimov Defendants to the Chancery Actions David Mumford Esq (instructed by Macfarlanes LLP) appeared for the Salford Defendants to the Chancery Actions Jonathan Adkin Esq and Watson Pringle Esq (instructed by Signature Litigation LLP) appeared for the Family Defendants to the Chancery Actions Hearing dates: 3rd – 7th October 2011; 10th – 13th October 2011; 17th – 19th October 2011; 24th & 28th October 2011; 31st October – 4th November 2011; 7th – 10th November 2011; 14th - 18th November 2011; 21st – 23 November 2011; 28th November – 2nd December 2011; 5th December 2011; 19th & 20th December 2011; 17th – 19th January 2012. -

Russia Intelligence

N°18 - October 11 2007 Published every two weeks/International Edition CONTENTS GEORGIA P. 1/4 GEORGIA c A small metter of settling c A small metter of settling scores between "friends scores between "friends P. 2 DUSHANBE SUMMITS Since the end of September, Georgia has been facing one of the most serious political crises c Vladimir Putin tries the country has known since its “Rose Revolution” of the autumn of 2003. The former Defense Min- to breathe new life into ister, Irakli Okruashvili, who came back to Georgia after six months in voluntary exile in the the CIS United Kingdom and in Ukraine, announced that he had formed an opposition party – Movement P. 3 TURKMENISTAN For a United Georgia – and attacked President Mikhail Saakashvili head-on. c The balancing act of Berdymukhammedov In a televised declaration on September 25, Okruashvili accused the president of having ac- KAZAKHSTAN c The redrawing quired most of his wealth illegally, and of having tried to cover up extortion charges against his of oligarch circles uncle, Temur Alasania. However, the former Prime Minister’s main allegations against the pres- ident are political in nature. Okruashvili declared that Saakashvili had, on several occasions, or- dered the attack or the assassination of opponents. One of the most sensational of these allega- tions is that the president told him to “get rid of” Badri Patarkatsishvili, the owner of the Imedi READ ALSO… media group, whose television channel is considered to favor the opposition. The former minister also hinted that the Interior Minister, Vano Merabishvili and the head of the Constitutional Se- RUSSIA INTELLIGENCE curity Department, Dato Akhalia, were directly implicated in the 2006 murder of the banker San- www.russia-intelligence.fr dro Girgvliani, for which several officials from the Interior Ministry were sentenced. -

BASEES Sampler

R O U T L E D G E . TAYLOR & FRANCIS Slavonic & East European Studies A Chapter and Journal Article Sampler www.routledge.com/carees3 Contents Art and Protest in Putin's Russia by Laurien 1 Crump Introduction Freedom of Speech in Russia edited by Piotr 21 Dutkiewicz, Sakwa Richard, Kulikov Vladimir Chapter 8: The Putin regime: patrimonial media The Capitalist Transformation of State 103 Socialism by David Lane Chapter 11: The move to capitalism and the alternatives Europe-Asia Studies 115 Identity in transformation: Russian speakers in Post- Soviet Ukrane by Volodymyr Kulyk Post-Soviet Affairs 138 The logic of competitive influence-seeking: Russia, Ukraine, and the conflict in Donbas by Tatyana Malyarenko and Stefan Wolff 20% Discount Available Enjoy a 20% discount across our entire portfolio of books. Simply add the discount code FGT07 at the checkout. Please note: This discount code cannot be combined with any other discount or offer and is only valid on print titles purchased directly from www.routledge.com. www.routledge.com/carees4 Copyright Taylor & Francis Group. Not for distribution. 1 Introduction It was freezing cold in Moscow on 24 December 2011 – the day of the largest mass protest in Russia since 1993. A crowd of about 100 000 people had gathered to protest against electoral fraud in the Russian parliamentary elections, which had taken place nearly three weeks before. As more and more people joined the demonstration, their euphoria grew to fever pitch. Although the 24 December demonstration changed Russia, the period of euphoria was tolerated only until Vladimir Putin was once again installed as president in May 2012. -

John Dunlop “Storm in Moscow” a Plan of the El’Tsin “Family” to Destabilize Russia

John Dunlop “Storm in Moscow” A Plan of the El’tsin “Family” to Destabilize Russia “Storm in Moscow” A Plan of the El’tsin “Family” to Destabilize Russia John B. Dunlop Hoover Institution CSSEO Working Paper No. 154 March 2012 Centro Studi sulla Storia dell’Europa Orientale Via Tonelli 13 – 38056 Levico Terme (Tn) Italy tel/fax: 0461 702137 e-mail: [email protected] John Dunlop “Storm in Moscow”: A Plan of the El’tsin “Family” to Destabilize Russia CSSEO Working Paper No. 154 March 2012 © 2012 by Centro Studi sulla Storia dell’Europa Orientale 2 “Truth always wins. The lie sooner or later evaporates and the truth remains.”1 (Boris El’tsin, Midnight Diaries, 2000) This paper was originally presented at an October 2004 seminar held at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), Johns Hopkins University, Washington DC. The seminar was hosted by Professor Bruce Parrott, at the time Director of Russian and Eurasian Studies at SAIS. The essay was subsequently revised to take into consideration comments made by the seminar’s two discussants, Professor Peter Reddaway of George Washington University and Donald N. Jensen, Director of Communications at Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty in Washington (and currently Senior Fellow, Center for Transatlantic Relations, Voice of America). In March of 2005, the paper was posted on the SAIS web-site (sais-jhu.edu). Eventually the paper was retired from the jhu.edu web-site.2 By the current year, 2011, it had become clear that an updated and revised version of the paper was needed, one which would take into consideration significant new information which has come to light since 2005. -

Georgia and Ukraine: Similar Revolutions, Different Trajectories

EURASIA DAILY MONITOR Volume 4 , Issue 211 (November 13, 2007) GEORGIA AND UKRAINE: SIMILAR REVOLUTIONS, DIFFERENT TRAJECTORIES By Taras Kuzio The ongoing political crisis in Georgia shares similar roots with the September 2005 crisis in Ukraine (see EDM, September 8, 14, 16, 2005). The Georgian crisis began when former defense minister Irakli Okruashvili accused President Mikheil Saakashvili of money laundering, misuse of power, and instigating violence against his opponents. Arrested on corruption charges, Okruashvili retracted his accusations and then fled abroad. In Ukraine two years ago, the head of the presidential secretariat and former head of President Viktor Yushchenko’s 2004 election campaign, Oleksandr Zinchenko, also accused the president’s entourage of corruption, although not of violence. Both insiders made their accusations without producing evidence. This is a frequent tactic in former Soviet states; that is, using accusations of corruption to discredit opponents. It is difficult to see how the opposition’s accusations against Saakashvili can be taken seriously, when the Georgian opposition is headed by Badri Patarkatsishvili. One of the wealthiest oligarchs in Georgia, Patarkatsishvili made his fortune through rather murky means in the 1990s by working for the now-exiled Russian oligarch Boris Berezovsky. Both Okruashvili and Zinchenko used the accusations to launch opposition political parties that have failed to attract voters. With 0.04% of the vote, Zinchenko’s Patriots bloc placed 44th out of 45 parties in the 2006 parliamentary elections, and it did not contest the September 2007 vote. Okruashvili’s Movement for a United Georgia may share a similar fate if he does not return. -

Who Owns Georgia's Media

Who Owns Georgia’s Media tbilisi, 2018 Authors: Salome Tsetskhladze Mariam Gogiashvili Co-author and research supervisor Mamuka Andguladze The publication has been prepared with the financial support of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Transparency International Georgia is solely responsible for the report’s content. The views expressed in the report do not necessarily represent those of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Contents Introduction ______________________________________________________________ 4 Key findings ______________________________________________________________ 6 Rustavi 2 Holding ________________________________________________________ 7 Imedi Media Holding ______________________________________________________ 11 Iberia TV __________________________________________________________________ 15 TV Pirveli __________________________________________________________________ 18 Obieqtivi TV ________________________________________________________________ 21 Palitra TV __________________________________________________________________ 22 R.B.G. ____________________________________________________________________ 25 Stereo + ____________________________________________________________________ 26 Media concentration ________________________________________________________ 27 Recommendations ________________________________________________________ 30 Introduction Television is Georgia’s most popular medium, representing the main source of information on political issues for decades1 and having a significant -

The Information Specialist's Method: Klebnikov Quotes the Tycoon's Published Scint—-Which Be Later Bought, with the the More He Talked up His Eonnections, the Denials

I H of the Italian songs; but it was fascinating cover of a novel near Caines's head (it was cable foe). Instead Klebnikov gives us Z m to see him summarily and radically edit Elective Affinities). They tapped on the three hundred harrowing pages to convey his work for the requirements of a differ- glass to tr\' to get him to acknowledge that Berezovsky is the "godfather of god- ent venue. their presence. He told me later that after fathers." When Klebnikov first invoked the Caines is a genuinely .surprising artist. the third tap, he learned that if he sighed g-word, in a Forbes profile in December The same month, for the "Deli Dances" or shifted his weight slightly when they 1996, Berezovsky sued for libel. Recently, m series, where dancers peribrmed in knocked, he satisfied their demands and the Russian won the right to sue the Amer- Chashama's storefront window, he con- they stopped. ican magazine in a British court. With the c structed two installations. In one, wearing Some day, I have no douht, he will put appearance of Godfather of the Kremlin, CD shorts and an eyeshade, he simply slept however, it may be time for Berezovsky I- that lesson into play in a dance. At the (or tried to sleep) on a mat for two hours, moment, for November performances at to sue Klebnikov for impersonating his o with a small collection of over-the- The Construction Company, Caines is publicity agent. counter remedies for insomnia lined up preparing a trio to four Worid War I-era next to him. -

Berezovsky Abramovich Summary Amended

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF THE FULL JUDGMENT OF GLOSTER J IN Berezovsky v Abramovich Action 2007 Folio 942 Introduction 1. This is an executive summary of my full judgment in this action. The full judgment is the definitive judgment and this summary is provided simply for the convenience of the parties and the public. 2. In action 2007 Folio 942, which I shall refer to as the Commercial Court action, the claimant, Boris Abramovich Berezovsky sues the defendant, Roman Arkadievich Abramovich for sums in excess of US dollars (“$”) 5.6 billion. 3. Both men are Russian citizens and are, or were, successful businessmen. Mr. Berezovsky fled from Russia to France on 30 October 2000, following a public dispute with Vladimir Putin, who was elected President of the Russian Federation in March 2000. Mr. Berezovsky subsequently settled in England and applied for asylum in the United Kingdom on 27 October 2001. His application was accepted on 10 September 2003. He is now resident in England. 1 October 2012 16:28 Page 1 4. At the time Mr. Berezovsky fled Russia, he had substantial commercial interests in the Russian Federation. According to his United Kingdom tax returns, he remains domiciled in Russia for tax purposes and intends to return to Russia when the political situation permits him to do so. 5. Mr. Abramovich frequently visits England because of his ownership of Chelsea Football Club. He also had substantial commercial interests in the Russian Federation at material times for the purposes of this litigation. 6. Jurisdiction in the action was founded on service, or attempted service, of the claim form personally on Mr. -

Russia Intelligence

N°22 -December 6 2007 Published every two weeks / International Edition CONTENTS KYRGYZSTAN P. 1 KYRGYZSTAN c Wariness Reigns Ahead of December 16 Election c Wariness Reigns Ahead of December 16 Election Can President Kurmanbek Bakiev and his entourage refrain from taking all the seats in the P. 2&3 GEORGIA Jogorku Kenesh when snap parliamentary elections are held on December 16? Will they be able to re- c Election Campaign and frain from taking advantage of administrative resources after having set up exceptionally restrictive ru- Political Maneuvering in les for the game? Given that his position is hardly as solid as that of Vladimir Putin and Nursultan Na- Georgia zarbaev, will Bakiev be capable of sharing power ? DEFENSE P. 4 c Kazakhstan Builds its Caspian Sea Fleet The possible misuse of power is what is feared by most of the twelve parties vying for the 90 seats at stake, on a party list system, even though the potential is there to make this election one of the ALERT c Kazakhstan to Preside most contested that the young republic has ever known. The parliamentary election could usher in ei- OSCE in 2010 ther a renewal of political turmoil, or the end of the chaos that has reigned since the fall of President Akaev in March 2005. There is nothing to encourage an optimistic outlook. On November 28, Prime Mi- nister Almaz Atambaev, head of the Social Democratic Party of Kyrgyzstan (SDPK), resigned from his READ ALSO… government post. According to the party’s secretary, Edil Baisalov, the Prime Minister threw in the RUSSIA INTELLIGENCE towel because he “told President Bakiev to his face that Ak Jol (his party, “the bright path”) and go- www.russia-intelligence.fr vernment officials were interfering in the election process.” Many members of political parties and KREMLIN NGOs condemn the ruling coalition’s use of administrative resources and of the media. -

Georgia - Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on Tuesday 25 August 2015

Georgia - Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on Tuesday 25 August 2015 Information on Imedi television network, particularly the branch in Kutaisi A report issued in December 2007 by Human Rights Watch states: “The popular Imedi television station was founded in 2002 by wealthy businessman Badri Patarkatsishvili, a former close associate of exiled Russian tycoon Boris Berezovsky. Imedi became increasingly critical of the authorities after Patarkatsishvili fell out with Saakashvili’s government in 2006, allegedly amidst business disputes. The station aired investigative pieces into controversial subjects, including on the murder of Sandro Girgvliani, head of United Georgian Bank’s international relations department, by Ministry of Interior employees in January 2006…Government officials criticized Imedi, calling it an opposition mouthpiece, and refused all invitations to participate in debates or talk shows on Imedi” (Human Rights Watch (19 December 2007) Crossing the Line, Georgia’s Violent Dispersal of Protestors and Raid on Imedi Television, p.13). In June 2014 a publication released by the NATO Parliamentary Assembly states: “The editorial policy of another popular TV channel Imedi has shifted more to the centre since the ownership of the channel was returned to its original majority shareholder, the family of Badri Patarkatsishvili, shortly after the 2012 elections” (NATO Parliamentary Assembly (1 June 2014) Georgia's Euro-Atlantic Integration: Internal and External Challenges, point 60). A publication