Assessment of the Status of Himalayan Lynx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Audit Report on the Accounts of District Government Chitral Audit Year 2016

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT GOVERNMENT CHITRAL AUDIT YEAR 2016-17 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .............................................................. ii Preface ................................................................................................................... iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................... v SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS ................................................................... viii Table 1: Audit Work Statistics ................................................................................................. viii Table 2: Audit observations Classified by Categories (Rs in million) ...................................... viii Table 3: Outcome Statistics ........................................................................................................ ix Table 4: Table of Irregularities pointed out ................................................................................. x Table 5: Cost Benefit Ratio ......................................................................................................... x CHAPTER 1 ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 District Government Chitral ......................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. -

Eurasian Lynx – Your Essential Brief

Eurasian lynx – Your essential brief Background Q: Are lynx native to Britain? A: Based on archaeological evidence, the range of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) included Britain until at least 1,300 years ago. It is difficult to be precise about when or why lynx became extinct here, but it was almost certainly related to human activity – deforestation removed their preferred habitat, and also that of their prey, thus reducing prey availability. These declines in prey species may have been exacerbated by human hunting. Q: Where do they live now? A: Across Europe, Scandinavia, Russia, northern China and Southeast Asia. The range used to include other areas of Western Europe, including Britain, where they are no longer present. Q: How many are there? A: There are thought to be around 50,000 in the world, of which 9,000 – 10,000 live in Europe. They are considered to be a species of least concern by the IUCN. Modern range of the Eurasian lynx Q: How big are they? A: Lynx are on average around 1m in length, 75cm tall and around 20kg, with the males being slightly larger than the females. They can live to 15 years old, but this is rare in the wild. Q: What do they eat? A: The preferred prey of the lynx are the smaller deer species, primarily the roe deer. Lynx may also prey upon other deer species, including chamois, sika deer, smaller red deer, muntjac and fallow deer. Q: Do they eat other things? A: Yes. Lynx prey on many other species when their preferred prey is scarce, including rabbits, hares, foxes, wildcats, squirrel, pine marten, domestic pets, sheep, goats and reared gamebirds. -

An Ounce of Prevention: Snow Leopard Crime Revisited (PDF, 4

TRAFFIC AN OUNCE REPORT OF PREVENTION: Snow Leopard Crime Revisited OCTOBER 2016 Kristin Nowell, Juan Li, Mikhail Paltsyn and Rishi Kumar Sharma TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC, the wild life trade monitoring net work, is the leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC International as the copyright owner. Financial support for TRAFFIC’s research and the publication of this report was provided by the WWF Conservation and Adaptation in Asia’s High Mountain Landscapes and Communities Project, funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC network, WWF, IUCN or the United States Agency for International Development. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Nowell, K., Li, J., Paltsyn, M. and Sharma, R.K. (2016). An Ounce of Prevention: Snow Leopard Crime Revisited. -

Status of Large Carnivores in Serbia

Status of large carnivores in Serbia Duško Ćirović Faculty of Biology University of Belgrade, Belgrade Status and threats of large carnivores in Serbia LC have differend distribution, status and population trends Gray wolf Eurasian Linx Brown Bear (Canis lupus) (Lynx lynx ) (Ursus arctos) Distribution of Brown Bear in Serbia Carpathian Dinaric-Pindos East Balkan Population status of Brown Bear in Serbia Dinaric-Pindos: Distribution 10000 km2 N=100-120 Population increase Range expansion Carpathian East Balkan: Distribution 1400 km2 Dinaric-Pindos N= a few East Balkan Population trend: unknown Carpathian: Distribution 8200 km2 N=8±2 Population stable Legal status of Brown Bear in Serbia According Law on Protection of Nature and the Law on Game and Hunting brown bear in Serbia is strictly protected species. He is under the centralized jurisdiction of the Ministry of Environmental Protection Treats of Brown Bear in Serbia Intensive forestry practice and infrastructure development . Illegal killing Low acceptance due to fear for personal safety Distribution of Gray wolf in Serbia Carpathian Dinaric-Pindos East Balkan Population status of Gray wolf in Serbia Dinaric-Balkan: 2 Carpathian Distribution cca 43500 km N=800-900 Population - stabile/slight increasingly Dinaric Range - slight expansion Carpathian: Distribution 480 km2 (was) Population – a few Population status of Gray wolf in Serbia Carpathian population is still undefined Carpathian Peri-Carpathian Legal status of Gray wolf in Serbia According the Law on Game and Hunting the gray wolf in majority pars of its distribution (south from Sava and Danube rivers) is game species with closing season from April 15th to July 1st. -

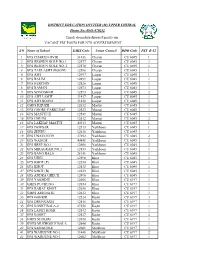

S.# Name of School EMIS Code Union Council DDO Code PST B-12 1

DISTRICT EDUCATION OFFICER (M) UPPER CHITRAL Phone No: 0943-470252 Email: [email protected] VACANT PST POSTS FOR NTS ADVERTISEMENT S.# Name of School EMIS Code Union Council DDO Code PST B-12 1 GPS CHARUN OVIR 31436 Charun CU 6045 1 2 GPS RESHUN GOLE NO.1 12577 Charun CU 6045 1 3 GPS RESHUN GOLE NO..2 12578 Charun CU 6045 1 4 GPS TAKLASHT (BOONI) 12596 Charun CU 6045 1 5 GPS AWI 12497 Laspur CU 6045 1 6 GPS BALIM 12499 Laspur CU 6045 1 7 GPS HERCHIN 12526 Laspur CU 6045 1 8 GPS RAMAN 12573 Laspur CU 6045 1 9 GPS SONOGHUR 12593 Laspur CU 6045 2 10 GPS AWI LASHT 31437 Laspur CU 6045 1 11 GPS AWI BOONI 31438 Laspur CU 6045 1 12 GMPS KHUZH 12632 Mastuj CU 6045 1 13 GPS GHORU PARKUSAP 12523 Mastuj CU 6045 1 14 GPS MASTUJ II 12549 Mastuj CU 6045 1 15 GPS CHUINJ 12512 Mastuj CU 6045 2 16 GPS LAKHAP MASTUJ 40313 Mastuj CU 6045 1 17 GPS DEWSAR 12513 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 18 GPS ZHUPU 12610 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 19 GPS UNAVOUCH 37292 Yarkhoon CU 6045 2 20 GPS WASUM 40841 Yarkhoon CU 6045 2 21 GPS BREP NO.1 12508 Yarkhoon CU 6045 2 22 GPS MIRAGRAM NO.2 12553 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 23 GPS BANG BALA 28141 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 24 GPS UJNU 12598 Khot CU 6045 1 25 GPS KHOT (P) 12534 Khot CU 6045 1 26 GPS KHOT 12532 Khot CU 6045 1 27 GPS KHOT (B) 12533 Khot CU 6045 1 28 GPS ANDRA GHECH 12496 Khot CU 6045 1 29 GPS YAKHDIZ 12606 Khot CU 6197 1 30 GMPS PUCHUNG 12654 Khot CU 6197 1 31 GPS RABAT KHOT 12656 Khot CU 6197 1 32 GMPS AMUNATE 12612 Khot CU 6197 1 33 GPS GOHKIR 12524 Kosht CU 6197 3 34 GPS DRUNGAGH 12516 Kosht CU 6197 1 35 GPS KOSHT BALA-2 27550 Kosht -

For Peer Review Only

BMJ Open BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006238 on 26 November 2014. Downloaded from Emerging role of traditional birth attendants in mountainous terrain of Chitral District, Pakistan ForJournal: peerBMJ Open review only Manuscript ID: bmjopen-2014-006238 Article Type: Research Date Submitted by the Author: 27-Jul-2014 Complete List of Authors: Shaikh, Babar; Aga Khan Foundation, Pakistan, Health & Built Environment Khan, Sharifullah; Aga Khan Foundation, Health & Built Environment Maab, Ayesha; Aga Khan Foundation, Health & Built Environment Amjad, Sohail; Aga Khan Foundation, Health & Built Environment <b>Primary Subject Health services research Heading</b>: Health policy, Obstetrics and gynaecology, Public health, Qualitative Secondary Subject Heading: research, Reproductive medicine Health policy < HEALTH SERVICES ADMINISTRATION & MANAGEMENT, Keywords: Organisation of health services < HEALTH SERVICES ADMINISTRATION & MANAGEMENT, Public health < INFECTIOUS DISEASES http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ on September 28, 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. For peer review only - http://bmjopen.bmj.com/site/about/guidelines.xhtml Page 1 of 19 BMJ Open BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006238 on 26 November 2014. Downloaded from 1 2 3 Emerging role of traditional birth attendants in mountainous terrain of Chitral District, Pakistan 4 5 6 7 Babar Tasneem Shaikh, PhD, FRCP Edin - Aga Khan Foundation 8 9 Sharifullah Khan, MPH - Aga Khan Foundation 10 11 Ayesha Maab, MSc - Aga Khan Foundation 12 13 Sohail Amjad, MPH - Aga Khan Foundation 14 15 For peer review only 16 17 18 19 Running title: Role of traditional birth attendants 20 21 22 23 24 25 Corresponding author 26 27 Dr Babar Tasneem Shaikh 28 29 Aga Khan Foundation (Pakistan) 30 31 Level Nine, Serena Business Complex 32 33 Khayaban-e-Suharwardy, Islamabad 34 http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ 35 t: +92 51 111-253-254 36 37 f: +92 51 2072552 38 39 e: [email protected] 40 41 42 on September 28, 2021 by guest. -

Pdf 325,34 Kb

(Final Report) An analysis of lessons learnt and best practices, a review of selected biodiversity conservation and NRM projects from the mountain valleys of northern Pakistan. Faiz Ali Khan February, 2013 Contents About the report i Executive Summary ii Acronyms vi SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. The province 1 1.2 Overview of Natural Resources in KP Province 1 1.3. Threats to biodiversity 4 SECTION 2. SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS (review of related projects) 5 2.1 Mountain Areas Conservancy Project 5 2.2 Pakistan Wetland Program 6 2.3 Improving Governance and Livelihoods through Natural Resource Management: Community-Based Management in Gilgit-Baltistan 7 2.4. Conservation of Habitats and Species of Global Significance in Arid and Semiarid Ecosystem of Baluchistan 7 2.5. Program for Mountain Areas Conservation 8 2.6 Value chain development of medicinal and aromatic plants, (HDOD), Malakand 9 2.7 Value Chain Development of Medicinal and Aromatic plants (NARSP), Swat 9 2.8 Kalam Integrated Development Project (KIDP), Swat 9 2.9 Siran Forest Development Project (SFDP), KP Province 10 2.10 Agha Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) 10 2.11 Malakand Social Forestry Project (MSFP), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 11 2.12 Sarhad Rural Support Program (SRSP) 11 2.13 PATA Project (An Integrated Approach to Agriculture Development) 12 SECTION 3. MAJOR LESSONS LEARNT 13 3.1 Social mobilization and awareness 13 3.2 Use of traditional practises in Awareness programs 13 3.3 Spill-over effects 13 3.4 Conflicts Resolution 14 3.5 Flexibility and organizational approach 14 3.6 Empowerment 14 3.7 Consistency 14 3.8 Gender 14 3.9. -

The Toledo Zoo/Thinkingworks Teacher Overview for the Cat Lessons

The Toledo Zoo/ThinkingWorks Teacher Overview for the Cat Lessons Ó2003 Teacher Overview: Cheetah, Lion, Snow Leopard and Tiger The cheetah, lion, snow leopard and tiger have traits that are unique to their particular species. Below is a list of general traits for each species that will help you and your students complete the ThinkingWorks lesson. The cheetah, lion, snow leopard and tiger belong to the class of vertebrate (e.g., animals with a backbone) animals known as Mammalia or Mammals. This group is characterized by live birth, suckling young with milk produced by the mother, a covering of hair or fur and warm-bloodedness (e.g., capable of producing their own body heat). The class Mammalia is further broken down into smaller groups known as orders and families. The cheetah, snow leopard and tiger belong to the order Carnivora, a group typified as flesh-eating, with large canine teeth. Two of the many other members of this order include dogs (e.g., wolf, African wild dog and fox) bears (e.g., polar and black bear), weasels (e.g., skunk and otter) and seals (e.g., gray and harbor seal). The cheetah, lion, snow leopard and tiger also belong to the family Felidae, a family composed of many species including the leopard, jaguar, bobcat and puma. Cheetahs are currently exhibited on the historic side of the Zoo near the Museum and on the north side of the Zoo in the Africa! exhibit. Lions are exhibited in the Africa Savanna near the exit. Snow leopards are exhibited on the historic side between the sloth bear exhibit and the exit to the African Savanna. -

Prey Density, Environmental Productivity and Home-Range Size in the Eurasian Lynx (Lynx Lynx)

J. Zool., Lond. (2005) 265, 63–71 C 2005 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom DOI:10.1017/S0952836904006053 Prey density, environmental productivity and home-range size in the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) Ivar Herfindal1, John D. C. Linnell2*, John Odden2, Erlend Birkeland Nilsen1 and Reidar Andersen1,2 1 Department of Biology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, N-7491 Trondheim, Norway 2 Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, Tungasletta 2, N-7485 Trondheim, Norway (Accepted 19 May 2004) Abstract Variation in size of home range is among the most important parameters required for effective conservation and management of a species. However, the fact that home ranges can vary widely within a species makes data transfer between study areas difficult. Home ranges of Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx vary by a factor of 10 between different study areas in Europe. This study aims to try and explain this variation in terms of readily available indices of prey density and environmental productivity. On an individual scale we related the sizes of 52 home ranges, derived from 23 (9:14 male:female) individual resident lynx obtained from south-eastern Norway, with an index of density of roe deer Capreolus capreolus. This index was obtained from the density of harvested roe deer within the municipalities covered by the lynx home ranges. We found a significant negative relationship between harvest density and home- range size for both sexes. On a European level we related the sizes of 111 lynx (48:63 male: female) from 10 study sites to estimates derived from remote sensing of environmental productivity and seasonality. -

Sabin Snow Leopard Grant Program

Sabin Snow Leopard Grant Program The Andrew Sabin Family Foundation and Panthera have partnered to launch the new Sabin Snow Leopard Grants Program, which will provide up to $100,000 a year to support in situ conservation projects on snow leop- ards. Awards of up to $20,000 per project will be made for one year, but may be extended to subsequent years, contingent upon performance and results. ELIGIBILITY Applications may be made by individuals, or institutions. In the latter case, the project leader must be identified and make the submission. Application is open to all qualified candidates but projects led by country nationals and/or in country NGOs will be given priority. SPECIES AND LOCATION The Sabin Snow Leopard Grants Program supports applications for in situ conservation efforts on the snow leop- ard in Asia. Emphasis will be given to requests for field conservation and research activities, including: • Applying interventions that directly and immediately mitigate threats to snow leopards including activities which measurably reduce the persecution of snow leopards by pastoralists and poachers, the illegal trade in snow leopards, and so on. • Monitoring and Research. We are very interested in survey efforts in areas of the snow leopard’s range for which there is limited or poor data, including developing baseline information on snow leopard populations; identifying and delineating important connections between known snow leopard populations; and undertak- ing basic research on snow leopard ecology where gaps exist. BUDGET GUIDELINES The maximum allowable request is $20,000 per annum. Panthera will consider local salaries, per diems, and sti- pends for local field personnel only; we will not fund salaries for core administrative and management personnel. -

Current Status of the Eurasian Lynx. Cat News. (2016)

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 10 | Autumn 2016 CatsCAT in Iran news 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, a component Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the International Union Co-chairs IUCN/SSC for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is published twice a year, and is Cat Specialist Group available to members and the Friends of the Cat Group. KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, Switzerland For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send <[email protected]> contributions and observations to [email protected]. Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews Cover Photo: From top left to bottom right: Caspian tiger (K. Rudloff) This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with support Asiatic lion (P. Meier) from the Wild Cat Club and Zoo Leipzig. Asiatic cheetah (ICS/DoE/CACP/ Panthera) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh caracal (M. Eslami Dehkordi) Layout: Christine Breitenmoser & Tabea Lanz Eurasian lynx (F. Heidari) Print: Stämpfli Publikationen AG, Bern, Switzerland Pallas’s cat (F. Esfandiari) Persian leopard (S. B. Mousavi) ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group Asiatic wildcat (S. B. Mousavi) sand cat (M. R. Besmeli) jungle cat (B. Farahanchi) The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Project Snow Leopard

PROJECT SNOW LEOPARD Ministry of Environment and Forests PROJECT SNOW LEOPARD Ministry of Environment and Forests CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1 2. Project Justification 5 3. Project Objectives 11 4. Project Areas 15 4.1. Criteria for determining landscapes 18 5. Broad management principles 19 5.1. Management approach 21 5.2. Management initiatives 22 5.3. Strategy for reaching out 24 5.4. Research 24 6. Indicative Activities under Project 27 7. Administration 31 8. Financial Implications 35 9. Conclusion 37 10. Time-lines 39 11. Annexures 41 1. Details of the Project Snow Leopard, Drafting Committee instituted by the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India, (vide Notification No. F.No., 15/5/2006 WL I, Dated 31 July 2006) 41 2. Recommendations of the National Workshop on ‘Project Snow Leopard’ held on 11-12 July, 2006 at Leh-Ladakh 42 3. Known protected areas in the Indian high altitudes (including the Trans-Himalaya and Greater Himalaya) with potential for snow leopard occurrence (Rodgers et al. 2000, WII Database and inputs from the respective Forest/Wildlife Departments). 43 4. List of PAs in the Five Himalayan States. PAs in the snow leopard range are seperately iden tified (based on WII Database and inputs from state Forest/Wildlife Departments) 44 12. Activity Flow chart 48 FOREWORD The Indian Himalaya have numerous unique ecosystems hidden within, which house rich biodiversity including a wealth of medicinal plants, globally important wildlife, besides providing ecological, aesthetic, spiritual and economic services. A significant proportion of these values is provided by high altitude areas located above the forests – the alpine meadows and the apparently bleak cold deserts beyond, an area typified by the mystical apex predator, the snow leopard, which presides over the stark landscape inhabited by its prey including a variety of wild sheep and goats.