For Peer Review Only

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Audit Report on the Accounts of District Government Chitral Audit Year 2016

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT GOVERNMENT CHITRAL AUDIT YEAR 2016-17 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .............................................................. ii Preface ................................................................................................................... iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................... v SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS ................................................................... viii Table 1: Audit Work Statistics ................................................................................................. viii Table 2: Audit observations Classified by Categories (Rs in million) ...................................... viii Table 3: Outcome Statistics ........................................................................................................ ix Table 4: Table of Irregularities pointed out ................................................................................. x Table 5: Cost Benefit Ratio ......................................................................................................... x CHAPTER 1 ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 District Government Chitral ......................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. -

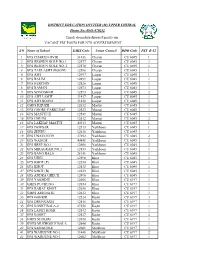

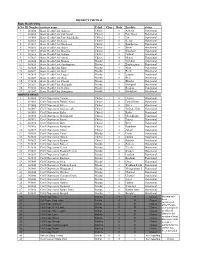

S.# Name of School EMIS Code Union Council DDO Code PST B-12 1

DISTRICT EDUCATION OFFICER (M) UPPER CHITRAL Phone No: 0943-470252 Email: [email protected] VACANT PST POSTS FOR NTS ADVERTISEMENT S.# Name of School EMIS Code Union Council DDO Code PST B-12 1 GPS CHARUN OVIR 31436 Charun CU 6045 1 2 GPS RESHUN GOLE NO.1 12577 Charun CU 6045 1 3 GPS RESHUN GOLE NO..2 12578 Charun CU 6045 1 4 GPS TAKLASHT (BOONI) 12596 Charun CU 6045 1 5 GPS AWI 12497 Laspur CU 6045 1 6 GPS BALIM 12499 Laspur CU 6045 1 7 GPS HERCHIN 12526 Laspur CU 6045 1 8 GPS RAMAN 12573 Laspur CU 6045 1 9 GPS SONOGHUR 12593 Laspur CU 6045 2 10 GPS AWI LASHT 31437 Laspur CU 6045 1 11 GPS AWI BOONI 31438 Laspur CU 6045 1 12 GMPS KHUZH 12632 Mastuj CU 6045 1 13 GPS GHORU PARKUSAP 12523 Mastuj CU 6045 1 14 GPS MASTUJ II 12549 Mastuj CU 6045 1 15 GPS CHUINJ 12512 Mastuj CU 6045 2 16 GPS LAKHAP MASTUJ 40313 Mastuj CU 6045 1 17 GPS DEWSAR 12513 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 18 GPS ZHUPU 12610 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 19 GPS UNAVOUCH 37292 Yarkhoon CU 6045 2 20 GPS WASUM 40841 Yarkhoon CU 6045 2 21 GPS BREP NO.1 12508 Yarkhoon CU 6045 2 22 GPS MIRAGRAM NO.2 12553 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 23 GPS BANG BALA 28141 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 24 GPS UJNU 12598 Khot CU 6045 1 25 GPS KHOT (P) 12534 Khot CU 6045 1 26 GPS KHOT 12532 Khot CU 6045 1 27 GPS KHOT (B) 12533 Khot CU 6045 1 28 GPS ANDRA GHECH 12496 Khot CU 6045 1 29 GPS YAKHDIZ 12606 Khot CU 6197 1 30 GMPS PUCHUNG 12654 Khot CU 6197 1 31 GPS RABAT KHOT 12656 Khot CU 6197 1 32 GMPS AMUNATE 12612 Khot CU 6197 1 33 GPS GOHKIR 12524 Kosht CU 6197 3 34 GPS DRUNGAGH 12516 Kosht CU 6197 1 35 GPS KOSHT BALA-2 27550 Kosht -

Pdf 325,34 Kb

(Final Report) An analysis of lessons learnt and best practices, a review of selected biodiversity conservation and NRM projects from the mountain valleys of northern Pakistan. Faiz Ali Khan February, 2013 Contents About the report i Executive Summary ii Acronyms vi SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. The province 1 1.2 Overview of Natural Resources in KP Province 1 1.3. Threats to biodiversity 4 SECTION 2. SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS (review of related projects) 5 2.1 Mountain Areas Conservancy Project 5 2.2 Pakistan Wetland Program 6 2.3 Improving Governance and Livelihoods through Natural Resource Management: Community-Based Management in Gilgit-Baltistan 7 2.4. Conservation of Habitats and Species of Global Significance in Arid and Semiarid Ecosystem of Baluchistan 7 2.5. Program for Mountain Areas Conservation 8 2.6 Value chain development of medicinal and aromatic plants, (HDOD), Malakand 9 2.7 Value Chain Development of Medicinal and Aromatic plants (NARSP), Swat 9 2.8 Kalam Integrated Development Project (KIDP), Swat 9 2.9 Siran Forest Development Project (SFDP), KP Province 10 2.10 Agha Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) 10 2.11 Malakand Social Forestry Project (MSFP), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 11 2.12 Sarhad Rural Support Program (SRSP) 11 2.13 PATA Project (An Integrated Approach to Agriculture Development) 12 SECTION 3. MAJOR LESSONS LEARNT 13 3.1 Social mobilization and awareness 13 3.2 Use of traditional practises in Awareness programs 13 3.3 Spill-over effects 13 3.4 Conflicts Resolution 14 3.5 Flexibility and organizational approach 14 3.6 Empowerment 14 3.7 Consistency 14 3.8 Gender 14 3.9. -

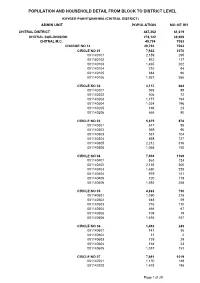

Chitral Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (CHITRAL DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH CHITRAL DISTRICT 447,362 61,619 CHITRAL SUB-DIVISION 278,122 38,909 CHITRAL M.C. 49,794 7063 CHARGE NO 14 49,794 7063 CIRCLE NO 01 7,933 1070 001140101 2,159 295 001140102 972 117 001140103 1,465 202 001140104 716 94 001140105 684 96 001140106 1,937 266 CIRCLE NO 02 4,157 664 001140201 593 89 001140202 505 72 001140203 1,171 194 001140204 1,024 196 001140205 198 23 001140206 666 90 CIRCLE NO 03 5,875 878 001140301 617 85 001140302 569 96 001140303 551 104 001140304 858 127 001140305 2,212 316 001140306 1,068 150 CIRCLE NO 04 7,939 1169 001140401 863 124 001140402 2,135 300 001140403 1,650 228 001140404 979 141 001140405 720 118 001140406 1,592 258 CIRCLE NO 05 4,883 730 001140501 1,590 218 001140502 448 59 001140503 776 110 001140504 466 67 001140505 109 19 001140506 1,494 257 CIRCLE NO 06 1,492 243 001140601 141 36 001140602 11 2 001140603 139 29 001140604 164 23 001140605 1,037 153 CIRCLE NO 07 7,691 1019 001140701 1,170 149 001140702 1,478 195 Page 1 of 29 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (CHITRAL DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 001140703 1,144 156 001140704 1,503 200 001140705 1,522 196 001140706 874 123 CIRCLE NO 08 9,824 1290 001140801 2,779 319 001140802 1,605 240 001140803 1,404 200 001140804 1,065 152 001140805 928 124 001140806 974 135 001140807 1,069 120 CHITRAL TEHSIL 228,328 31846 ARANDU UC 23,287 3105 AKROI 1,777 301 001010105 1,777 301 ARANDU -

Emerging Role of Traditional Birth Attendants in Mountainous Terrain: a Qualitative Exploratory Study from Chitral District, Pakistan

Open Access Research BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006238 on 26 November 2014. Downloaded from Emerging role of traditional birth attendants in mountainous terrain: a qualitative exploratory study from Chitral District, Pakistan Babar Tasneem Shaikh, Sharifullah Khan, Ayesha Maab, Sohail Amjad To cite: Shaikh BT, Khan S, ABSTRACT et al Strengths and limitations of this study Maab A, . Emerging role Objectives: This research endeavours to identify the of traditional birth attendants role of traditional birth attendants (TBAs) in supporting ▪ in mountainous terrain: A study, the first of its kind, which has expounded the maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) care, a qualitative exploratory study on the subject of traditional birth attendants from Chitral District, Pakistan. partnership mechanism with a formal health system (TBAs)’ role and livelihood after the introduction of BMJ Open 2014;4:e006238. and also explored livelihood options for TBAs in the trained maternal, newborn and child health provi- doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014- health system of Pakistan. ders in Pakistan. 006238 Setting: The study was conducted in district Chitral, ▪ The use of qualitative methods provided rich Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, covering the areas insight into women’s interpretations and ▸ Prepublication history for where the Chitral Child Survival programme was decision-making regarding healthcare seeking this paper is available online. implemented. during and after pregnancy in a relatively conser- To view these files please Participants: A qualitative exploratory study was vative setting of Pakistan. The study presents the visit the journal online conducted, comprising seven key informant interviews views of all stakeholders involved in the (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ with health managers, and four focus group discussions intervention. -

Military Report and Gazetteer Chitral - General Staff India

.' FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY. MOBILIZATION. This book is the property of the Government- of India. NOTE. The information given in this book is not to be communicated either directly OY indirec~ly lo the Press or to any prson not holding an official posi~ion in His Majsty's Service. MILITARY REPORT AND GAZETTEER CHITRAL - GENERAL STAFF INDIA (2nd Edition.) 1928 CALOUTTA GOVERNMEKT OF INDIA PREBB 1928 This publication renders obsolete the " Military Report on Chitral, 1st Edition, 1904." Officers are particularly requested to bring to notice any errors or omissions in this publication, or any further authentic information on the subjects dealt with. Such communications should be addressed, through the usual channels, to :- TABLE OF CONTENTS. PART I. PAQX. Chapter I.-History . 1 ,, 11.-Geography : Section I.-Physical Features . , 11.--Climate end health . ,, 111.-Places of strategical and tactical importance . ,, 111.-Population . ,, 1V.-Resources : Section I.-General . , 11.--Supplies . ,, 111.-Transport . , V.-Armed Forces : Section I.-General . Appendir I.-Mountain ranges and principal pease8 . 73 ,, 11.-Principal rivers and their tributaries . 86 ,, 111.-V/T. signalling stations . 104 ,, IV.-Beacon sites-Mastuj to Barogbil . 112 ,, V.-Epitome of principal routes in Chitral . 113 ,, V1.-Notes on the more importent personagee inchitre1 . 118 Pa~:orama from Arandu (Arnamai) looking S.S.W. towards Birkot . Frontispiece Plate 2.-Sarhad-i-Wakhan and R. Oxus . To face page 20 Plate 3.-Cantilever bridgv, M'arkhup . To face page 71 9% .....NAPS. Map 1.--Urtzun-Naghr zone-Chitral Defence Map 3-~ignallin~Chart No. scheme Rich River route . PassandChitral . Map 5.-Map of Chitral and adjacent countries . -

Status of Snow Leopard and Prey Species in Torkhow Valley, District Chitral, Pakistan

Din and Nawaz The Journal of Animal & Plant Sciences, 21(4): 2011, Page: J.836 Anim.-840 Plant Sci. 21(4):2011 ISSN: 1018-7081 STATUS OF SNOW LEOPARD AND PREY SPECIES IN TORKHOW VALLEY, DISTRICT CHITRAL, PAKISTAN J. U. Din and M. A. Nawaz * Snow Leopard Foundation, Pakistan, 17- Service Road North, I-8/3, Islamabad *Department of Animal Sciences, Quaid-I-Azam University, Islamabad Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The study was conducted from June – October 2007 and was aimed at assessing the status of snow leopard, its major prey base, and the extent of human-snow leopard conflict in northern Chitral (Torkhow Valley). Snow leopard occurrence was conformed through sign surveys using Snow Leopard Information Management System (SLIMS) protocol. Based on the data collected the number of snow leopards in the study area (1022 km²) was estimated to be 2-3 animals. Highest sign density was seen in Shah Junali (12.8/km), followed by Ujnu Gol (5.8) and Ziwar Gol (2.8). Extrapolating these estimates to the entire Chitral District, gives a population estimate of 36 snow leopards for the district. The livestock depredation reports collected from the area reflected 138 cases affecting 102 families (in a period of eight years, 2001-2008), indicating existence of serious human-snow leopard conflicts. Using point count method during the rut season, a total of 429 Himalayan ibex were counted in the area. The ibex is the only wild ungulate and primary prey for snow leopards in the study. Other carnivores recorded from the area included wolf, jackal, and fox. -

Exploring the Energy Consumption Environmental Impacts and Economic Consequences Of

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Graduate Capstones 2018 Exploring the energy consumption environmental impacts and economic consequences of Qureshi, Nazish Qureshi, N. (2018). Exploring the energy consumption environmental impacts and economic consequences of (Unpublished report). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/33095 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/108743 report University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY “Exploring the energy consumption, environmental impacts and economic consequences of implementing in-house solar cookers in Chitral.” by Nazish Qureshi A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE GRADUATE PROGRAM IN SUSTAINABLE ENERGY DEVELOPMENT CALGARY, ALBERTA AUGUST, 2018 © Nazish Qureshi 2018 ABSTRACT The ‘Theory of Himalayan Environmental Degradation’, as described by Ali & Benjaminsen (2004), is concerning for many. Chitral is a beautiful remote valley in north-west Pakistan, nestled in Hindu Raj, Hindu Kush and Karakoram-Himalayan mountain ranges. In the absence of other fuel options, about 99% of Chitral’s population uses traditional firewood stoves for cooking. To alleviate the consequent burdens of deforestation, pollution and health hazards, my analysis explores the feasibility of implementing solar cookers in Chitral. I make an energy comparison, study the environmental impacts and determine the economic viability of this transition. -

Auditor General of Pakistan

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF LOCAL GOVERNMENTS DISTRICT CHITRAL AUDIT YEAR 2018-19 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ............................................................... i Preface .................................................................................................................. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................. iii SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS .................................................................... vii I: Audit Work Statistics ....................................................................................... vii II: Audit observations Classified by Categories ................................................... vii III: Outcome Statistics ....................................................................................... viii IV: Table of Irregularities pointed out .................................................................. ix V: Cost Benefit Ratio ........................................................................................... ix CHAPTER-1 ........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Local Governments Chitral .................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) ..................... 5 1.1.3 Comments on the status -

S.No ID Number Institute Name Tehsil Class Beds Locality Status 1 343004 Basic Health Unit Asherat Chitral 1 0 Asherat Functiona

DISTRICT CHITRAL Basic Health Units S.No ID Number institute name Tehsil Class Beds Locality status 1 343004 Basic Health Unit Asherat Chitral 1 0 Asherat Functional 2 343005 Basic Health Unit Pati Nagar Chitral 1 0 Pati Nagar Functional 3 343008 Basic Health Unit Tar (Shishikoh) Chitral 1 0 Tar Functional 4 343012 Basic Health Unit Kesu Chitral 1 0 Kessu Functional 5 343013 Basic Health Unit Bumborat Chitral 1 0 Bumborate Functional 6 343016 Basic Health Unit Broze Chitral 1 0 Broze Functional 7 343017 Basic Health Unit Shoghore Chitral 1 0 Shoghore Functional 8 343018 Basic Health Unit Goboor Chitral 1 0 Goboor Functional 9 343021 Basic Health Unit Moroi Chitral 1 0 Moroi Functional 10 343024 Basic Health Unit Niskoo Mastuj 1 0 Nishkoo Functional 11 343025 Basic Health Unit Zondragram Mastuj 1 0 Zondragrame Functional 12 343026 Basic Health Unit Khot Mastuj 1 0 Khot Functional 13 343027 Basic Health Unit Rech Mastuj 1 0 Rech Functional 14 343028 Basic Health Unit Laspur Mastuj 1 0 Laspur Functional 15 343029 Basic Health Unit Brep Mastuj 1 0 Brep Functional 16 343030 Basic Health Unit Khosht Mastuj 1 0 Khosht Functional 17 343031 Basic Health Unit Shongush Mastuj 1 0 shongush Functional 18 343032 Basic Health Unit Reshun Mastuj 1 0 Reshun Functional 19 343047 Basic Health Unit Sonoghore Mastuj 1 0 Sonoghore Functional DISPENSARIES 1 343002 Civil Dispensary Ursoon Chitral 1 0 Ursoon Functional 2 343003 Civil Dispensary Damail Nisar Chitral 1 0 Damil Nisar Functional 3 343006 Civil Dispensary Sweer Chitral 1 0 Sweer Functional 4 343007 -

District Project Description BE 2017-18 CHITRAL LOWER

District Project Description BE 2017-18 CHITRAL LOWER CL15000012-Improvement/Rehabilitation of DWSS atMasjid Quba - Shahnigar and Tek Azurdam Drosh CHITRAL LOWER CL15000018-"Improvement/Rehabilitation of DWSS atMakar - gole,Traur and Laugurbat Paeen Masjid" CHITRAL LOWER CL15000019-Construction DWSS Ustrum Shishikoh - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000020-Construction/Repair of water tankHakimabad - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000021-"Provision of Pipe for WSS - Lalmibakarabad,Ghaziabad, orghoch and Tor deh chumurkhon" CHITRAL LOWER CL15000023-Provision of Pipe line for WSS atKoghuzi - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000024-Pipe line at Bakamak Maidan and PachiliOchosht - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000025-Water Tank at Alian - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000029-Water tank at Dolomos - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000030-Construction of Water Well Broze Kol - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000031-Provision of pipe Maskoor - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000032-Water tank at Mixhi Gram - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000033-Water tank at Izh - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000034-Rehabilitation of WSS Zalabad Arkari - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000035-Rehabilitation of WSS Shagram maidan - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000036-WSS at Galah - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000038-WSS at Ghurdan Dagh - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000039-Improvement of Water Supply SchemeOtresh Barenis - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000040-Improvement of WSS Sheli Lasht - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000041-"improvement of Water Supply SchemeDomon tek - sheli, bebolak, Hindustan, achingole bakarabad and Faiz abadkoh Chumurkhon" CHITRAL LOWER CL15000042-Repair of Water Tank at DHQ HospitalChitral - CHITRAL LOWER CL15000043-Pipeline for -

Local Adaptation Strategies Chitral, Pakistan NEW.Indd

Traditional Knowledge and Local Institutions Support Adaptation to Water-Induced Hazards in AGA KHAN RURAL SUPPORT PROGRAM Chitral, Pakistan (A Project of Aga Khan Foundation) Executive summary The central objective of the research project ‘Documenting and Assessing Adaptation Strategies to Too Much, Too Little Water’ is to document adaptation strategies at local or community level to constraints and hazards related to water and induced by climate change in the Himalayan region, including how people are affected by water stress and hazards, their local short and long-term responses, and the extent to which these strategies reduce vulnerability to water stress and hazards. Five case studies were carried out in four countries. The results of each have been summarised in separate documents on a CD-ROM to accompany a single synthesis document. The Pakistan case study presented here documents and assesses people’s responses to fl ash fl oods and water stresses in two union councils respectively, Shishikoh and Mulkhow, in Chitral district, North West Frontier Province (NWFP). Flash fl oods happen frequently in Shishikoh, whereas in Mulkhow dry weather prevails for most of the year. Data collection methods included focus group discussions, key informant interviews and direct observations. The livelihoods in both Mulkhow and Shishikoh depend heavily on natural resources. Due to remote location and limited development interventions, opportunities for diversifying livelihoods are almost negligible and this makes them extremely vulnerable to the impacts of water stresses and fl oods. Climate-induced hazards such as fl ash fl oods and water scarcity have had negative impacts on the livelihoods of the inhabitants.