PDF File Created from a TIFF Image by Tiff2pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1992 Assembly 1311

QUESTIONS WITHOUT NOTICE Thursday, 7 May 1992 ASSEMBLY 1311 Thursday, 7 May 1992 Mr Kennett interjected. Ms KIRNER - I actually manage to listen occaSionally in the House, which is more than the Leader of the Opposition does because he does not The SPEAKER (Hon. Ken Coghill) took the chair at agree with the shadow Treasurer on most things. 10.34 a.m. and read the prayer. The Leader of the Opposition is smiling, but it is interesting that when this House debates things like the Auditor-General's report, the opposition QUESTIONS WITHOUT NOTICE spokesman is missing from the House. Where is he now? I cannot see him! Perhaps he has gone to do another radio program to abuse people! Where is STATE ELECTION he? Here he is! Isn't that nice! Mr KENNEIT (Leader of the Opposition) - I Honourable members interjecting. refer the Premier to her often repeated claim of being a community-based politician and I ask: at The SPEAKER - Order! I warn the Leader of the what stage will she put the community's interests OppOSition. He is well aware of the provisions of ahead of her and the government's selfishness, Standing Orders. I expect him to observe the same sorts of standards in this House that he requires in incompetence and dishonesty in managing the meetings that he chairs. affairs of the community she claims to represent by immediately calling an election? Ms KIRNER - No doubt the shadow Treasurer Ms KIRNER (Premier) - I thank the Leader of was out practising his calculated abuse of individuals on the telephone. -

Hutchinsmbdec2005.Pdf

Magenta ANDBlack Print Post approved PP 739016/00028 Hutchins School Newsletter December 2005 Our Community There are events during the year School) was inaugurated in Tasmania that express the importance and the to afford a means of training up the depth and breadth of our Hutchins youth of Tasmania…” Community. I feel a strong sense of community As people’s connections with and tradition when flanked by some churches lessen, the School is asked 700 boys singing in the Cathedral. to hold funeral services for its current students and its Old Boys. We are The farewelling of our Leavers by very happy to do this and glad that the ELC choir brings a tear to the the School can provide support in eye because the journey for our such sad and stressful times. Father Year Twelves in the School is just John is a tower of strength on such concluding, and they are brought face occasions and his role is greatly to face with where they started all appreciated. those years ago. The ELC boys are these nights are people who have young, perhaps a little uncertain and touched and been touched by our We broke with tradition this year and yet to experience that journey. It is community. Old Boys, parents, moved the Anniversary Service from the juxtaposition of the younger boys grandparents, friends, staff, students Sunday evening to a time during with all their youthful exuberance and specially invited guests come the school day. While this may and the older boys who have lost together to celebrate our community. -

27 March 2012 (Extract from Book 4)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Tuesday, 27 March 2012 (Extract from book 4) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable ALEX CHERNOV, AC, QC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry Premier and Minister for the Arts................................... The Hon. E. N. Baillieu, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Police and Emergency Services, Minister for Bushfire Response, and Minister for Regional and Rural Development.................................................. The Hon. P. J. Ryan, MP Treasurer........................................................ The Hon. K. A. Wells, MP Minister for Innovation, Services and Small Business, and Minister for Tourism and Major Events...................................... The Hon. Louise Asher, MP Attorney-General and Minister for Finance........................... The Hon. R. W. Clark, MP Minister for Employment and Industrial Relations, and Minister for Manufacturing, Exports and Trade ............................... The Hon. R. A. G. Dalla-Riva, MLC Minister for Health and Minister for Ageing.......................... The Hon. D. M. Davis, MLC Minister for Sport and Recreation, and Minister for Veterans’ Affairs . The Hon. H. F. Delahunty, MP Minister for Education............................................ The Hon. M. F. Dixon, MP Minister for Planning............................................ -

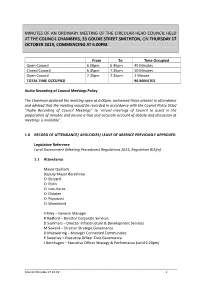

Minutes of an Ordinary Meeting of the Circular Head Council Held at the Council Chambers, 33 Goldie Street Smithton, on Thursday 17 October 2019, Commencing at 6.00Pm

MINUTES OF AN ORDINARY MEETING OF THE CIRCULAR HEAD COUNCIL HELD AT THE COUNCIL CHAMBERS, 33 GOLDIE STREET SMITHTON, ON THURSDAY 17 OCTOBER 2019, COMMENCING AT 6.00PM. From To Time Occupied Open Council 6.00pm 6.45pm 45 Minutes Closed Council 6.45pm 7.35pm 50 Minutes Open Council 7.35pm 7.36pm 1 Minute TOTAL TIME OCCUPIED 96 MINUTES Audio Recording of Council Meetings Policy The Chairman declared the meeting open at 6.00pm, welcomed those present in attendance and advised that the meeting would be recorded in accordance with the Council Policy titled “Audio Recording of Council Meetings” to ‘record meetings of Council to assist in the preparation of minutes and ensure a true and accurate account of debate and discussion at meetings is available’. 1.0 RECORD OF ATTENDANCE/ APOLOGIES/ LEAVE OF ABSENCE PREVIOUSLY APPROVED Legislative Reference Local Government (Meeting Procedures) Regulations 2015; Regulation 8(2)(a) 1.1 Attendance Mayor Quilliam Deputy Mayor Berechree Cr Blizzard Cr Ettlin Cr Ives-Heres Cr Oldaker Cr Popowski Cr Woodward S Riley – General Manager R Radford – Director Corporate Services D Summers – Director Infrastructure & Development Services M Saward – Director Strategic Governance D Mainwaring – Manager Connected Communities K Sweeney – Executive Officer Civic Governance J Bernhagen – Executive Officer Strategy & Performance (until 6.20pm) ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Council Minutes 17 10 19 1 1.2 Prayers Pastor Matt Nuske from Dreambuilders Church led the meeting in prayer. 1.3 Leave of Absence(s) previously approved Nil 1.4 Apologies Cr Kay 2.0 CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETING Legislative Reference Local Government (Meeting Procedures) Regulations 2015; Regulation 8(2) (b) MOVED: CR POPOWSKI SECONDED: CR IVES-HERES That the Minutes of the Ordinary Meeting 19 September 2019, a copy of which having previously been circulated to Councillors prior to the meeting, be confirmed as a true record. -

Sports Funding: Federal Balancing Act

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services BACKGROUND NOTE 27 June 2013 Sports funding: federal balancing act Dr Rhonda Jolly Social Policy Section Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Part 1: Federal Government involvement in sport .................................................................................. 3 From Federation to the Howard Government.................................................................................... 3 Federation to Whitlam .................................................................................................................. 3 Whitlam: laying the foundations of a new sports system ............................................................. 4 Fraser: dealing with the Montreal ‘crisis’ ...................................................................................... 5 Figure 1: comment on Australia’s sports system in light of its unspectacular performance in Montreal ............................................................................................................ 6 Table 1: summary of sports funding: Whitlam and Fraser Governments ..................................... 8 Hawke and Keating: a sports commission, the America’s Cup and beginning a balancing act ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Basis of policy .......................................................................................................................... -

Welcome to a More Rewarding Membership

MARCH 2018 | NO.168 | ISSN 1322-3771 MCC News Welcome to a more rewarding membership. to find out more see pages 10-11 CLUB NEWS Prominent members mourned he club has been left deeply saddened by the loss of three Tprominent, long-time members with significant links in the community. Ron Walker AO CBE died on January 30, aged 78 and had been an MCC member for almost 58 years. A former Lord Mayor of Melbourne, businessman and prominent Liberal Party figure, Walker was chairman of Melbourne Major Events Company, the body that helped attract new events to Victoria and the MCG. The club worked closely with Walker in his role as chairman of Melbourne 2006, the organising body for the 2006 Ron Walker Commonwealth Games. The completion of the northern stand redevelopment in time for that major event allowed the MCG to be the main stadium for the opening and editor with The Age for almost four and closing ceremonies. decades, he received the Walkley Award The Hon Alec Southwell QC died on for Most Outstanding Contribution to Australia Day, aged 91, and had been a Journalism late last year. member for nearly six decades. Gordon’s connections to the MCC and Southwell served with distinction on the MCG are many. His daughter, Sarah, is MCC Committee for 18 years (1979-97), a former MCC employee. Together with the last nine as a vice-president. He was his father, the late Harry Gordon, who a highly regarded judge, who served for 10 was a prominent journalist and Olympic years in the County Court and 18 years in historian, Michael co-authored the revised the Supreme Court. -

The Assertion of Tasmanian Aboriginality from the 1967 Referendum to Mabo

THE ASSERTION OF TASMANIAN ABORIGINALITY FROM THE 1967 REFERENDUM TO MABO BY Dennis W. Daniels B.A., B.Soe. Admin. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Humanities University of Tasmania, December 1995. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person, except when due reference is made in the text of the thesis. 'd dd Denn~sDaniels November 1995. Acknowledgments I wish to express my appreciation to Gillian Biscoe, Secretary of the Department of Community and Health Services, for permitting access to relevant material, and for Mary Bailey for facilitating the process. I am particularly grateful to the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre for approving the project and to those who granted personal interviews. Personal thanks to Tony Marshall of the Tasmanians section of the State Library. Thesis Abstract The Assertion of Aboriginality in Tasmania From the Referendum to Mabo This paper takes as its starting point a period before the 1967 Referendum which gave full citizenship rights to Australian Aborigines and the Federal Government a mandate over Aboriginal Affairs. During the 40's and 50's the Aboriginal people of Tasmania, represented by the people of Cape Barren Island, stubbornly resisted the assimilation policies of the day. In briefly examining the thesis of resistance as proposed by Lyndall Ryan in her 1981 edition of The Aboriginal Tasmanians, and the proposition that the Government sought to abandon the Island, the paper draws upon new material. -

Farewell to Ray Groom Great

Under The Stars REFLECTING LIFE’S JOURNEY... A Quarterly Publication of Southern Cross Care (Tas.) Inc. SPRING 2018 FAREWELL TO RAY GROOM Page 6 IN THIS ISSUE... SOUTHERN CROSS CARE (TAS.) INC. GREAT GRANDPARENTS DAYSpringhaven 2018 turning of the sod Photos and stories Page 8 TWO-WAY TAXI TRUCKS PH: 6273 1000 FURNITURE REMOVALIST, WAREHOUSE STORAGE, FORK HIRE & RENTAL 2 UNDER THE STARS – SPRING 2018 Under The Stars REFLECTING LIFE’S JOURNEY... SPRING 2018 A Quarterly Publication of Southern Cross Care (Tas.) Inc. FAREWELL TO RAY GROOM A Quarterly Magazine Page 6 IN THIS ISSUE published by Southern SPRING 2018 Cross Care (Tas.) Inc. ADDRESS 85 Creek Road New Town 7008 Great Grandparents Day celebrated in style at Glenara Lakes with resident Gaye How with granddaughter Chloe, daughter Janine and SOUTHERN CROSS CARE (TAS.) INC. IN THIS ISSUE... GREAT GRANDPARENTSSpringhaven DAY 2018 grandchild Lochie Moylonkjlk. turning of the Page sod 8 POSTAL Photos and stories P.O. Box 815 Moonah TAS 7009 CONTENTS Email: [email protected] FROM THE EDITOR 4 Ph: 6214 9717 YARAANDOO – KIDZ BIZ 5 EDITOR FAREWELL TO RAY GROOM 6 Michael Swinson GREAT GRANDPARENTS DAY SPECIAL 8 Email: [email protected] FAIRWAY RISE APARTMENTS – REMEMBERANCE 14 FEATURE CONTRIBUTORS SHOWTIME WITH ERIC BYRNE 15 John Birkett MOUNT ESK – TEAM BONDING 16 Eric Byrne MONEY MATTERS WITH SHIREEN DIEZ 17 Shireen Diez ROSARY GARDENS – LEUEY THE BLACKBIRD 18 Dean Ewington Pat Flanagan WINE NOTES WITH DAVID JOHNSTONE 19 David Johnstone GLENARA LAKES VILLAS – ROYAL WEDDING COCKTAIL -

Tasmanian Football Hall of Fame Record Photo Courtesy of the Launceston Examiner CONTENTS

ALL OF FAME HA TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME RECORD Photo courtesy of The Launceston Examiner CONTENTS CHAIRMAN'S MESSAGE 4 SELECTION CRITERIA 5 CALL FOR NOMINATIONS 2015 5 2014 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME ICONS 6 2014 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME LEGENDS 10 2014 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME INDUCTEES 12 2014 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME GREAT CLUB 18 2014 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME LEGENDARY TEAM 22 2014 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME MEMORABLE GAME 26 2014 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME SPECIAL INDUCTION "TEAM OF THE DECADE" 28 2014 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME LISTS 30 Special thanks to our media partners The Advocate, Examiner Newspaper and Mercury Newspaper for providing photos for this publication and to The Wade Gleeson and Ray Aitchison Collection and Joe J Cowburn Collection for providing photos of the New Norfolk District Football Club. 2014 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME 3 CHIEF EXECUTIVE'S MESSAGE Welcome to the tenth Tasmanian Football Hall of Fame induction dinner at Wrest Point. It seems like only yesterday that we conducted our Tasmanian Team of the Century dinner in 2004, followed by our inaugural Hall of Fame induction dinner in 2005. This is just another example of how quickly a decade passes by when you work in an industry as dynamic as Australian Football. Over this decade 277 individuals have entered our Hall of Fame ‘club’ as inductees. We have elevated 40 of these men to Legend status and further elevated just 14 to become Icons of Tasmanian Football. To be one of just 14 Icons to have been identified in over 149 years of the game being played in Tasmania is very special indeed. -

Tasmanian Football Hall of Fame Record Made in Tasmania for Tasmanians

ALL OF FAME HA TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME RECORD Made in Tasmania for Tasmanians Photo courtesy of The Launceston Examiner Courtesy of The Advocate CONTENTS CHAIRMAN'S MESSAGE 4 SELECTION CRITERIA 5 CALL FOR NOMINATIONS 2014 5 Made in 2013 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME ICONS 6 2013 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME LEGENDS 10 Tasmania 2013 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME INDUCTEES 12 2013 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME GREAT CLUB 16 for 2013 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME LEGENDARY TEAM 18 2013 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME MEMORABLE GAME 20 Tasmanians 2013 AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME 22 2013 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME LISTS 23 2013 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME 3 CHAIRMAN'S MESSAGE Welcome to our favourite event on the Tasmanian football calendar. AFL Tasmania devotes most of each year to focusing on the future; considering initiatives to grow our game for our community and for the benefit of the next generation of players, coaches, umpires, support staff, administrators and fans. While grand final day is always a special event for the participating clubs and their respective competitions, for AFL Tasmania our Tasmanian Football Hall of Fame is especially dear to our hearts because it is the only time during the year whereby we can pause for a brief moment and celebrate the past. In addition, we cherish the uniqueness of our Tasmanian Football Hall of Fame, which remains the only football event in the nation that enshrines great contributions from individuals, clubs, teams and games on a truly whole of state basis. We also recognise the special and distinctive elements of our great game in Tasmania such as the gravel oval in Queenstown and the King Island Football Association, to mention just two. -

The Social Construction of Joint Management in Kakadu National Park

Defined by contradiction: the social construction of joint management in Kakadu National Park Christopher David Haynes, B.Sc (For) School for Social and Policy Research Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Charles Darwin University July 2009 Title page: Digital camera case in one hand and mobile phone (it did not work) in the other, the author ponders the effects of globalisation to Kakadu’s ancient landscape and cultures at Twin Falls, one of Kakadu’s now-famous tourist icons, in a break during field work in 2005. (Photo: Liz Haynes). Abstract Born in the 1970s, a period when the Australian state needed to resolve land use conflicts in the then relatively remote Alligator Rivers region of Australia’s Northern Territory, Kakadu has become the nation’s largest and most famous national park. Aside from its worthy national park attributes and World Heritage status, it is also noted for its joint management, the sharing of management between the state and the traditional Aboriginal owners of the area. As an experienced park manager working in this park more than two decades after its declaration in 1979, I found joint management hard to comprehend and even harder to manage. In this thesis I explore this phenomenon as practice: how joint management works now, and how it came to be as it is. The work explains how the now accepted ‘best model’ for joint management – a legal arrangement based on land ownership by Aboriginal people, lease back to the state under negotiated conditions, a governing board of management with an Aboriginal majority, and regular consultation does not, on its own, satisfy either partner. -

Tasmanian Football Hall of Fame Record Photo Courtesy of the Launceston Examiner CONTENTS

LL OF FAM A E H Courtesy of Mercury Newspaper TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME RECORD Photo courtesy of The Launceston Examiner CONTENTS CHAIRMAN'S MESSAGE 4 SELECTION CRITERIA 5 CALL FOR NOMINATIONS 2013 5 2012 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME ICONS 6 2012 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME LEGEND 8 2012 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME INDUCTEES 10 2012 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME MEMORABLE GAME 14 2012 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME LEGENDAY TEAM 15 2012 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME SPECIAL CATEGORY 16 2012 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME GREAT CLUB 17 2012 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME TRIBUTE 18 2012 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME LISTS 19 2012 TASMANIAN FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME 3 CHAIRMAN'S MESSAGE Welcome to the 2012 Hall of Fame commemorative Special recognition must go to those current inductees Football Record. who are this year being elevated. AFL Tasmania, on behalf of the broader Tasmanian It is just wonderful to see Len Pye and Noel Atkins football community, is currently exploring a range of being granted Legend status and the elevation of Bruce exciting opportunities that will ensure that our great Carter and Brent Crosswell to become our eleventh and game continues to progress into the future. twelfth Icons in the Tasmanian Football Hall of Fame is due recognition for their outstanding records. In particular we are focusing on stakeholder relationships in an endeavour to provide Tasmanian football with a As Chairman of AFL Tasmania I am extremely pleased clearer management structure. Our strategic direction that my predecessors, Peter Hodgman and David Templeton, established the community aspect of our in terms of how we manage and administer our game is Hall of Fame.