California Project WET Gazette

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geologic Map of the Long Valley Caldera, Mono-Inyo Craters

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP 1-1933 US. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF LONG VALLEY CALDERA, MONO-INYO CRATERS VOLCANIC CHAIN, AND VICINITY, EASTERN CALIFORNIA By Roy A. Bailey GEOLOGIC SETTING VOLCANISM Long Valley caldera and the Mono-Inyo Craters Long Valley caldera volcanic chain compose a late Tertiary to Quaternary Volcanism in the Long Valley area (Bailey and others, volcanic complex on the west edge of the Basin and 1976; Bailey, 1982b) began about 3.6 Ma with Range Province at the base of the Sierra Nevada frontal widespread eruption of trachybasaltic-trachyandesitic fault escarpment. The caldera, an east-west-elongate, lavas on a moderately well dissected upland surface oval depression 17 by 32 km, is located just northwest (Huber, 1981).Erosional remnants of these mafic lavas of the northern end of the Owens Valley rift and forms are scattered over a 4,000-km2 area extending from the a reentrant or offset in the Sierran escarpment, Adobe Hills (5-10 km notheast of the map area), commonly referred to as the "Mammoth embayment.'? around the periphery of Long Valley caldera, and The Mono-Inyo Craters volcanic chain forms a north- southwestward into the High Sierra. Although these trending zone of volcanic vents extending 45 km from lavas never formed a continuous cover over this region, the west moat of the caldera to Mono Lake. The their wide distribution suggests an extensive mantle prevolcanic basement in the area is mainly Mesozoic source for these initial mafic eruptions. Between 3.0 granitic rock of the Sierra Nevada batholith and and 2.5 Ma quartz-latite domes and flows erupted near Paleozoic metasedimentary and Mesozoic metavolcanic the north and northwest rims of the present caldera, at rocks of the Mount Morrisen, Gull Lake, and Ritter and near Bald Mountain and on San Joaquin Ridge Range roof pendants (map A). -

Urban Drought Guidebook 2008 Updated Edition

Publications (WR) Water Resources 2008 Urban drought guidebook 2008 updated edition State of California Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/water_pubs Part of the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Repository Citation State of California (2008). Urban drought guidebook 2008 updated edition. 1-208. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/water_pubs/3 This Report is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Report in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Report has been accepted for inclusion in Publications (WR) by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UrbanUrban DroughtDrought GuidebookGuidebook 20082008 UpdatedUpdated EditionEdition StateState ofof CaliforniaCalifornia DepartmentDepartment ofof WaterWater ResourcesResources OfficeOffice ofof WaterWater UseUse EfficiencyEfficiency andand TransfersTransfers Cover Photo Lake Mead, storing Colorado River water that supplies irrigation and domestic water to much of Southern California at 50 percent capacity, winter 2007. Photo by Andy Pernick , U.S. Bureau of Reclamation photographer. If you need this publication in an alternate form, contact the Equal Opportunity and Management Investigations Offi ce at TDD 1-800-653-6934, or Voice 1-800-653-6952. -

Yosemite, Lake Tahoe & the Eastern Sierra

Emerald Bay, Lake Tahoe PCC EXTENSION YOSEMITE, LAKE TAHOE & THE EASTERN SIERRA FEATURING THE ALABAMA HILLS - MAMMOTH LAKES - MONO LAKE - TIOGA PASS - TUOLUMNE MEADOWS - YOSEMITE VALLEY AUGUST 8-12, 2021 ~ 5 DAY TOUR TOUR HIGHLIGHTS w Travel the length of geologic-rich Highway 395 in the shadow of the Sierra Nevada with sightseeing to include the Alabama Hills, the June Lake Loop, and the Museum of Lone Pine Film History w Visit the Mono Lake Visitors Center and Alabama Hills Mono Lake enjoy an included picnic and time to admire the tufa towers on the shores of Mono Lake w Stay two nights in South Lake Tahoe in an upscale, all- suites hotel within walking distance of the casino hotels, with sightseeing to include a driving tour around the north side of Lake Tahoe and a narrated lunch cruise on Lake Tahoe to the spectacular Emerald Bay w Travel over Tioga Pass and into Yosemite Yosemite Valley Tuolumne Meadows National Park with sightseeing to include Tuolumne Meadows, Tenaya Lake, Olmstead ITINERARY Point and sights in the Yosemite Valley including El Capitan, Half Dome and Embark on a unique adventure to discover the majesty of the Sierra Nevada. Born of fire and ice, the Yosemite Village granite peaks, valleys and lakes of the High Sierra have been sculpted by glaciers, wind and weather into some of nature’s most glorious works. From the eroded rocks of the Alabama Hills, to the glacier-formed w Enjoy an overnight stay at a Yosemite-area June Lake Loop, to the incredible beauty of Lake Tahoe and Yosemite National Park, this tour features lodge with a private balcony overlooking the Mother Nature at her best. -

Consequences of Drying Lake Systems Around the World

Consequences of Drying Lake Systems around the World Prepared for: State of Utah Great Salt Lake Advisory Council Prepared by: AECOM February 15, 2019 Consequences of Drying Lake Systems around the World Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................... 5 I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 13 II. CONTEXT ................................................................................. 13 III. APPROACH ............................................................................. 16 IV. CASE STUDIES OF DRYING LAKE SYSTEMS ...................... 17 1. LAKE URMIA ..................................................................................................... 17 a) Overview of Lake Characteristics .................................................................... 18 b) Economic Consequences ............................................................................... 19 c) Social Consequences ..................................................................................... 20 d) Environmental Consequences ........................................................................ 21 e) Relevance to Great Salt Lake ......................................................................... 21 2. ARAL SEA ........................................................................................................ 22 a) Overview of Lake Characteristics .................................................................... 22 b) Economic -

Introducing Terminal Lakes Joe Eilers and Ron Larson

Terminal Lakes Introducing Terminal Lakes Joe Eilers and Ron Larson Study Lakes akes tend to be among the more ephemeral features of the landscape Land generally are formed and disappear rapidly on a geological time frame. However, to see groups of lakes disappear within a lifetime is typically not a natural phenomenon. Here in Oregon, we’ve witnessed the desiccation of what was formerly a 16-mile-long lake in a little over a decade. Endorehic lakes, commonly referred to as terminal lakes because they lack an outlet, are among the most vulnerable of lakes to human intervention. Because terminal lakes are usually located in arid environments where water is extremely valuable, they are the first to lose among the competing forces for water. But that doesn’t have to be the case. In some respects, terminal lakes are far easier to restore than eutrophic/hypereutrophic systems. No expensive alum treatments, no dredging, no chemicals . just add water and life returns: but as those in West know, “Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting over.” And fight we must. In this issue of LakeLine, we describe a series of terminal lakes in the western United States starting with the least saline lake among the group, Walker Lake, and ending with Lake Winnemucca, which was desiccated in the 20th century (Figure 1). Like all lakes, each of these has a unique story to relate with different Figure 1. Terminal lakes in the western United States described in this issue. chemistry and biota. The loss of Lake Winnemucca is an informative tale, but it a wider audience and reach a solution migration when the birds replenish fat is not necessarily the inevitable outcome that ensures adequate water to save the reserves. -

Open-File/Color For

Questions about Lake Manly’s age, extent, and source Michael N. Machette, Ralph E. Klinger, and Jeffrey R. Knott ABSTRACT extent to form more than a shallow n this paper, we grapple with the timing of Lake Manly, an inconstant lake. A search for traces of any ancient lake that inundated Death Valley in the Pleistocene upper lines [shorelines] around the slopes Iepoch. The pluvial lake(s) of Death Valley are known col- leading into Death Valley has failed to lectively as Lake Manly (Hooke, 1999), just as the term Lake reveal evidence that any considerable lake Bonneville is used for the recurring deep-water Pleistocene lake has ever existed there.” (Gale, 1914, p. in northern Utah. As with other closed basins in the western 401, as cited in Hunt and Mabey, 1966, U.S., Death Valley may have been occupied by a shallow to p. A69.) deep lake during marine oxygen-isotope stages II (Tioga glacia- So, almost 20 years after Russell’s inference of tion), IV (Tenaya glaciation), and/or VI (Tahoe glaciation), as a lake in Death Valley, the pot was just start- well as other times earlier in the Quaternary. Geomorphic ing to simmer. C arguments and uranium-series disequilibrium dating of lacus- trine tufas suggest that most prominent high-level features of RECOGNITION AND NAMING OF Lake Manly, such as shorelines, strandlines, spits, bars, and tufa LAKE MANLY H deposits, are related to marine oxygen-isotope stage VI (OIS6, In 1924, Levi Noble—who would go on to 128-180 ka), whereas other geomorphic arguments and limited have a long and distinguished career in Death radiocarbon and luminescence age determinations suggest a Valley—discovered the first evidence for a younger lake phase (OIS 2 or 4). -

2021 Falling for the Migration

Falling for the Migration: Bridgeport, Crowley, Mono American Avocets in flight, photo by Bob Steele August 20–22, 2021 ● Dave Shuford $182 per person / $167 for Mono Lake Committee members enrollment limited to 10 participants Welcome to our field seminar on the fall migration of birds in the Bridgeport Valley and the adjacent Sierra, the Mono Basin, Crowley Lake, Long Valley, and the outskirts of Mammoth Lakes. Beginners as well as experts will enjoy this introduction to the area’s birdlife found in a wide variety of habitats, from the shimmering shores of Mono Lake to lofty Sierra peaks. We will identify about 100 species by plumage and calls, and probe the secrets of their natural history. This seminar will include informal discussions on migration strategies, behavior, and ecology that complement our field observations. This seminar will involve easy hiking at elevations ranging from 6,400 to 9,600 feet above sea level. We will hike 1–2 miles a day, mostly on level terrain. The first stop Friday morning is at Bridgeport Reservoir, a mecca for migrant and late‐breeding waterbirds. For those who prefer to meet the seminar at this location (arriving Friday morning from points north), please contact Nora Livingston at [email protected] or (760) 647‐6595 to obtain directions. Dave Shuford is an expert birder, avid naturalist and teacher, and a retired professional ornithologist. Dave’s bird research in the region includes a long‐term study on the ecology of Mono Lake’s California Gull colony, an atlas of breeding birds in the Glass Mountain area, and surveys of Snowy Plovers at Mono and Owens lakes. -

California-Ko Ostatuak: a History Of

3-79 Af&ti /Jo. 281? CALIFORNIA-KO OSTATUAK: A HISTORY OF CALIFORNIA'S BASQUE HOTELS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Jeronima (Jeri) Echeverria, B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas May, 1988 Echevenia, Jeronima (Jeri), Cal^fornia-ko Ostatuak: A History of California's Basque Hotels. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May, 1988, 282 pp., 14 tables, 15 illustrations, bibliography, 512 titles. The history of California's Basque boardinghouses, or ostatuak, is the subject of this dissertation. To date, scholarly literature on ethnic boardinghouses is minimal and even less has been written on the Basque "hotels" of the American West. As a result, conclusions in this study rely upon interviews, census records, local directories, early maps, and newspapers. The first Basque boardinghouses in the United States appeared in California in the decade following the gold rush and tended to be outposts along travel routes used by Basque miners and sheepmen. As more Basques migrated to the United States, clusters of ostatuak sprang up in communities where Basque colonies had formed, particularly in Los Angeles and San Francisco during the late nineteenth century. In the years between 1890 and 1940, the ostatuak reached their zenith as Basques spread throughout the state and took their boardinghouses with them. This study outlines the earliest appearances of the Basque ostatuak, charts their expansion, and describes their present state of demise. The role of the ostatuak within Basque-American culture and a description of how they operated is another important aspect of this dissertation. -

Most Recent Eruption of the Mono Craters, Eastern Central California

JOURNALOF GEOPHYSICALRESEARCH, VOL. 91, NO. B12, PAGES12,539-12,571, NOVEMBER10, 1986 MOST RECENT ERUPTION OF THE MONO CRATERS, EASTERN CENTRAL CALIFORNIA Kerry Sieh and Marcus Bursik Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena Abstract. The most recent eruption at the gradually diminishing explosiveness of the North Mono Craters occurred in the fourteenth century Mono eruption probably resulted from a decrease A.D. Evidence for this event includes 0.2 km3 of of water content downward in the dike. The pyroclastic fall, flow, and surge deposits and pulsating nature of the early, explosive phase of 0.4 km3 of lava domesand flows. These rhyolitic the eruption may represent the repeated rapid deposits emanated from aligned vents at the drawdown of slowly rising vesiculated magma to northern end of the volcanic chain. Hence we about the saturation depth of the water within have named this volcanic episode the North Mono it. eruption. Initial explosions were Plinian to sub-Plinian events whose products form Introduction overlapping blankets of air fall tephra. Pyroclastic flow and surge deposits lie upon Several dozen silicic eruptions have occurred these undisturbed fall beds within several along the tectonically active eastern flank of kilometers of the source vents. Extrusion of the central Sierra Nevada within the past 35,000 five domes and coulees, including Northern Coulee years; many of these eruptions have, in fact, and Panurn Dome, completed the North Mono occurred within the past 2000 years. This eruption. Radiocarbon dates and violent, exciting, and youthful past suggests an dendrochronological considerations constrain the interesting future and encouraged us to undertake eruption to a period between A.D. -

Arcgis Geostatistical Analyst Tutorial Copyright © 2001, 2003–2006 ESRI All Rights Reserved

ArcGIS® 9 ArcGIS Geostatistical Analyst Tutorial Copyright © 2001, 2003–2006 ESRI All Rights Reserved. Printed in the United States of America. The information contained in this document is the exclusive property of ESRI. This work is protected under United States copyright law and the copyright laws of the given countries of origin and applicable international laws, treaties, and/or conventions. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except as expressly permitted in writing by ESRI. All requests should be sent to Attention: Contracts Manager, ESRI, 380 New York Street, Redlands, CA 92373-8100, USA. The information contained in this document is subject to change without notice. DATA CREDITS Carpathian Mountains data supplied by USDA Forest Service, Riverside, California, and is used here with permission. Radioceasium data supplied by International Sakharov Environmental University, Minsk, Belarus, and is used here with permission. Copyright © 1996. Air quality data for California supplied by California Environmental Protection Agency, Air Resource Board, and is used here with permission. Copyright © 1997. Radioceasium contamination in forest berries data supplied by the Institute of Radiation Safety “BELRAD”, Minsk, Belarus, and is used here with permission. Copyright © 1996. CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Kevin Johnston, Jay M. Ver Hoef, Konstantin Krivoruchko, and Neil Lucas DATA DISCLAIMER THE DATA VENDOR(S) INCLUDED IN THIS WORK IS AN INDEPENDENT COMPANY AND, AS SUCH, ESRI MAKES NO GUARANTEES AS TO THE QUALITY, COMPLETENESS, AND/OR ACCURACY OF THE DATA. EVERY EFFORT HAS BEEN MADE TO ENSURE THE ACCURACY OF THE DATA INCLUDED IN THIS WORK, BUT THE INFORMATION IS DYNAMIC IN NATURE AND IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. -

Decline of the World's Saline Lakes

PERSPECTIVE PUBLISHED ONLINE: 23 OCTOBER 2017 | DOI: 10.1038/NGEO3052 Decline of the world’s saline lakes Wayne A. Wurtsbaugh1*, Craig Miller2, Sarah E. Null1, R. Justin DeRose3, Peter Wilcock1, Maura Hahnenberger4, Frank Howe5 and Johnnie Moore6 Many of the world’s saline lakes are shrinking at alarming rates, reducing waterbird habitat and economic benefits while threatening human health. Saline lakes are long-term basin-wide integrators of climatic conditions that shrink and grow with natural climatic variation. In contrast, water withdrawals for human use exert a sustained reduction in lake inflows and levels. Quantifying the relative contributions of natural variability and human impacts to lake inflows is needed to preserve these lakes. With a credible water balance, causes of lake decline from water diversions or climate variability can be identified and the inflow needed to maintain lake health can be defined. Without a water balance, natural variability can be an excuse for inaction. Here we describe the decline of several of the world’s large saline lakes and use a water balance for Great Salt Lake (USA) to demonstrate that consumptive water use rather than long-term climate change has greatly reduced its size. The inflow needed to maintain bird habitat, support lake-related industries and prevent dust storms that threaten human health and agriculture can be identified and provides the information to evaluate the difficult tradeoffs between direct benefits of consumptive water use and ecosystem services provided by saline lakes. arge saline lakes represent 44% of the volume and 23% of the of migratory shorebirds and waterfowl utilize saline lakes for nest- area of all lakes on Earth1. -

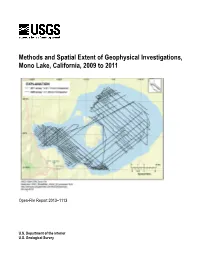

Methods and Spatial Extent of Geophysical Investigations, Mono Lake, California, 2009 to 2011

Methods and Spatial Extent of Geophysical Investigations, Mono Lake, California, 2009 to 2011 Open-File Report 2013–1113 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey FRONT COVER: Map showing location of seismic tracklines in Mono Lake: 2009 (solid lines), 68 tracklines, total 318 km; 2011 (dashed lines), 60 tracklines, total 199 km. Map prepared by Florence Wong, USGS Coastal and Marine Geology. Methods and Spatial Extent of Geophysical Investigations, Mono Lake, California, 2009 to 2011 By A.S. Jayko, P.E. Hart, J.R. Childs, M.H. Cormier, D.A.Ponce, N.D. Athens, and J.S. McClain Open-File Report 2013–1113 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2013 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Suggested citation: Jayko, A.S., Hart, P.E., Childs, J.R., Cormier, M.H., Ponce, D.A., Athens, N.A., and McClain, J.S., 2013, Methods and spatial extent of geophysical Investigations, Mono Lake, California, 2009 to 2011; U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2013–1113, 18 p., http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2013/1113/.