The Development of a Regional Plan for the Oslo Metropolitan Area SJPA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Permo-Carboniferous Oslo Rift Through Six Stages and 65 Million Years

52 by Bjørn T. Larsen1, Snorre Olaussen2, Bjørn Sundvoll3, and Michel Heeremans4 The Permo-Carboniferous Oslo Rift through six stages and 65 million years 1 Det Norske Oljeselskp ASA, Norway. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Eni Norge AS. E-mail: [email protected] 3 NHM, UiO. E-mail: [email protected] 4 Inst. for Geofag, UiO. E-mail: [email protected] The Oslo Rift is the northernmost part of the Rotliegen- des basin system in Europe. The rift was formed by lithospheric stretching north of the Tornquist fault sys- tem and is related tectonically and in time to the last phase of the Variscan orogeny. The main graben form- ing period in the Oslo Region began in Late Carbonif- erous, culminating some 20–30 Ma later with extensive volcanism and rifting, and later with uplift and emplacement of major batholiths. It ended with a final termination of intrusions in the Early Triassic, some 65 Ma after the tectonic and magmatic onset. We divide the geological development of the rift into six stages. Sediments, even with marine incursions occur exclusively during the forerunner to rifting. The mag- matic products in the Oslo Rift vary in composition and are unevenly distributed through the six stages along the length of the structure. Introduction The Oslo Palaeorift (Figure 1) contributed to the onset of a pro- longed period of extensional faulting and volcanism in NW Europe, which lasted throughout the Late Palaeozoic and the Mesozoic eras. Widespread rifting and magmatism developed north of the foreland of the Variscan Orogen during the latest Carboniferous and contin- ued in some of the areas, like the Oslo Rift, all through the Permian period. -

What's Inside

TAKE ONE! June 2014 Paving the path to heritage WHAT’S INSIDE President’s message . 2 SHA memorials, membership form . 10-11 Picture this: Midsummer Night . 3 Quiz on Scandinavia . 12 Heritage House: New path, new ramp . 4-5 Scandinavian Society reports . 13-15 SHA holds annual banquet . 6-7 Tracing Scandinavian roots . 16 Sutton Hoo: England’s Scandinavian connection . 8-9 Page 2 • June 2014 • SCANDINAVIAN HERITAGE NEWS President’s MESSAGE Scandinavian Heritage News Vol. 27, Issue 67 • June 2014 Join us for Midsummer Night Published quarterly by The Scandinavian Heritage Assn . by Gail Peterson, president man. Thanks to 1020 South Broadway Scandinavian Heritage Association them, also. So far 701/852-9161 • P.O. Box 862 we have had sev - Minot, ND 58702 big thank you to Liz Gjellstad and eral tours for e-mail: [email protected] ADoris Slaaten for co-chairing the school students. Website: scandinavianheritage.org annual banquet again. Others on the Newsletter Committee committee were Lois Matson, Ade - Midsummer Gail Peterson laide Johnson, Marion Anderson and Night just ahead Lois Matson, Chair Eva Goodman. (See pages 6 and 7.) Our next big event will be the Mid - Al Larson, Carroll Erickson The entertainment for the evening summer Night celebration the evening Jo Ann Winistorfer, Editor consisted of cello performances by Dr. of Friday, June 20, 2014. It is open to 701/487-3312 Erik Anderson (MSU Professor of the public. All of the Nordic country [email protected] Music) and Abbie Naze (student at flags will be flying all over the park. Al Larson, Publisher – 701/852-5552 MSU). -

THE LION FLAG Norway's First National Flag Jan Henrik Munksgaard

THE LION FLAG Norway’s First National Flag Jan Henrik Munksgaard On 27 February 1814, the Norwegian Regent Christian Frederik made a proclamation concerning the Norwegian flag, stating: The Norwegian flag shall henceforth be red, with a white cross dividing the flag into quarters. The national coat of arms, the Norwegian lion with the yellow halberd, shall be placed in the upper hoist corner. All naval and merchant vessels shall fly this flag. This was Norway’s first national flag. What was the background for this proclamation? Why should Norway have a new flag in 1814, and what are the reasons for the design and colours of this flag? The Dannebrog Was the Flag of Denmark-Norway For several hundred years, Denmark-Norway had been in a legislative union. Denmark was the leading party in this union, and Copenhagen was the administrative centre of the double monarchy. The Dannebrog had been the common flag of the whole realm since the beginning of the 16th century. The red flag with a white cross was known all over Europe, and in every shipping town the citizens were familiar with this symbol of Denmark-Norway. Two variants of The Dannebrog existed: a swallow-tailed flag, which was the king’s flag or state flag flown on government vessels and buildings, and a rectangular flag for private use on ordinary merchant ships or on private flagpoles. In addition, a number of special flags based on the Dannebrog existed. The flag was as frequently used and just as popular in Norway as in Denmark. The Napoleonic Wars Result in Political Changes in Scandinavia At the beginning of 1813, few Norwegians could imagine dissolution of the union with Denmark. -

Delprosjekt Eidsvoll

Norges vassdrags- og energidirektorat Telefon: 22 95 95 95 Middelthunsgate 29 Telefaks: 22 95 90 00 Postboks 5091 Majorstua Internett: www.nve.no 0301 Oslo Flomsonekart Delprosjekt Eidsvoll Ahmed Reza Naserzadeh Julio Pereira 2 2007 FLOMSONEKART Flomsonekart nr 2/2007 Delprosjekt Eidsvoll Utgitt av: Norges vassdrags- og energidirektorat Forfattere: Ahmed Reza Naserzadeh Julio Pereira Trykk: NVEs hustrykkeri Opplag: 100 Forsidefoto: Sundet, vårflommen 10.06.1995 ©FOTONOR ISSN: 1504-5161 Emneord: Flomsone, flom, flomanalyse, flomareal, flomberegning, vannlinjeberegning, Vorma, Mjøsa, Eidsvoll kommune Norges vassdrags- og energidirektorat Middelthuns gate 29 Postboks 5091 Majorstua 0301 OSLO Telefon: 22 95 95 95 Telefaks: 22 95 90 00 Internett: www.nve.no Januar 2007 Sammendrag Rapporten inneholder detaljer rundt flomsonekartlegging av Vorma, fra Steinerud til Minnesund, en strekning på totalt ca 11 km. Området ligger i Eidsvoll kommune i Akershus. Grunnlaget for flomsonekartene er flomfrekvensanalyse og vannlinjeberegninger. Digitale flomsoner for 10-, 100-, 200-, og 500-årsflom dekker hele den kartlagte strekningen. I tillegg er det gitt vannstander for 20-, og 50-årsflom. Det er produsert flomsonekart for et område ved Minnesund og ved Sundet. Flomsonekart for 200-årsflommen samt flomdybdekart for 200-årsflommen ved Sundet er vedlagt rapporten. For at de beregnede flommene skal være mest mulig representative for fremtiden, er det valgt å betrakte perioden etter 1961, dvs. perioden etter de viktigste reguleringene fant sted. Det er derfor ikke tatt hensyn til flommer før 1961. Det er vårflommene som er de største både i Mjøsa og i Vorma. De fleste opptrer fra slutten av mai til midten av juli. Flom i Vorma innebærer en langsom vannstandsstigning på grunn av Mjøsa. -

Ullensaker, Nannestad Og Eidsvoll Kommuner

FYLKESADMINISTRASJONEN Ullensaker kommune Postboks 470 2051 JESSHEIM Att. Atle Sander Vår saksbehandler Vår dato Vår referanse (oppgis ved svar) Margaret A. Mortensen 04.04.2018 2014/14795-28/47845/2018 EMNE L12 Telefon Deres dato Deres referanse 22055622 13.02.2018 2014/6151-42 Ullensaker, Eidsvoll og Nannestad kommuner - Detaljregulering for Sessvollmoen skyte- og øvingsfelt - Foreløpig uttalelse til offentlig ettersyn Det vises til kommunens oversendelse datert 13. februar 2018 av reguleringsplan til offentlig ettersyn i henhold til plan- og bygningsloven § 12-10. Planområdet er på drøyt 7 km2 og ligger hovedsakelig i Ullensaker kommune, men omfatter også arealer i Nannestad og Eidsvoll. Planforslaget er i hovedsak i samsvar med gjeldende kommuneplaner. Formålet med planen er å avklare og fastsette rammevilkårene for videre utbygging og drift av Sessvollmoen skyte- og øvingsfelt. Det opplyses at det primært foreligger planer om å modernisere eksisterende anlegg, ikke å utvide skyte- og øvingsfeltet. Tiltaket er vurdert ut fra fylkeskommunens rolle som regional planmyndighet og som fagmyndighet for kulturminnevern. Fylkesrådmannen viser til uttalelse datert 21. mai 2015 til varsel om igangsatt reguleringsarbeid for området og til øvrig korrespondanse knyttet til kulturminneverdiene i området, og har følgende merknader til planforslaget: Automatisk fredete kulturminner Planområdet ble registrert av Akershus fylkeskommune våren 2005 og høsten 2014, vår ref. 03/10966 og 2014/14795. Det ble gjort funn av automatisk fredete kulturminner som er i hensyntatt i plankartet med båndleggingssone H730 (båndlegging etter lov om kulturminner). Innenfor reguleringsområdet er det også registrert automatisk fredete kulturminner i form av flere kullgroper og kullmiler, id 91319. Dette kulturminnet er fredet i medhold av lov om kulturminner av 9. -

COWI AS Nedre Strandgate 3 3015 DRAMMEN Ullensaker Kommune

FYLKESADMINISTRASJONEN COWI AS Nedre Strandgate 3 3015 DRAMMEN Vår saksbehandler Vår dato Vår referanse (oppgis ved svar) Erlend Hansen Sjåvik 24.04.2017 2016/15422-11/70188/2017 EMNE L12 Telefon Deres dato Deres referanse 20.03.2017 Ullensaker kommune - Reguleringsplan - Gbnr 17/239 med flere - Bakkedalen idretts og skoleområde på Kløfta - Varsel om utvidelse Vi viser til brev fra Cowi AS av 20.03.2017. Tiltaket er vurdert ut fra fylkeskommunens rolle som regional planmyndighet og som fagmyndighet for kulturminnevern. Fylkesrådmannen tar varselet til orientering og har ingen ytterligere merknader. Med vennlig hilsen Erlend Hanssen Sjåvik Rådgiver plan Dokumentet er elektronisk godkjent. Kopi til: Statens vegvesen Region øst, Fylkesmannen i Oslo og Akershus Saksbehandlere: Planfaglige vurderinger: [email protected], 22 05 56 86 Automatisk fredete kulturminner: [email protected], 22 05 55 20 Nyere tids kulturminner: [email protected], 22 05 56 28 Postadresse Besøksadresse Telefon Org. nr - juridisk Postboks 1200 sentrum Schweigaardsgt 4, 0185 Oslo (+47) 22055000 NO 958381492 MVA 0107 OSLO E-post Fakturaadresse Telefaks Org. nr - bedrift [email protected] Pb 1160 Sentrum, 0107 Oslo (+47) 22055055 NO 874587222 Tordenskiolds gate 12 Postboks 8111 Dep, 0032 OSLO Telefon 22 00 35 00 [email protected] www.fmoa.no Organisasjonsnummer NO 974 761 319 Cowi AS Deres ref.: Nedre Strandgate 3 Deres dato: 20.03.2017 3015 DRAMMEN Vår ref.: 2017/14177-2 FM-M Saksbehandler: Christina Kinck Direktetelefon: 22003708 Dato: 21.04.2017 Ullensaker kommune - Varsel om utvidelse av Bakkedalen idretts- og skoleområde - Fylkesmannens uttalelse - Fylkesmannens uttalelse Vi viser til brev fra Cowi AS av 20.03.2017. -

Agenda 2030 in Asker

Agenda 2030 in Asker Voluntary local review 2021 Content Opening Statement by mayor Lene Conradi ....................................4 Highlights........................................................................................5 Introduction ....................................................................................6 Methodology and process for implementing the SDGs ...................8 Incorporation of the Sustainable Development Goals in local and regional frameworks ........................................................8 Institutional mechanisms for sustainable governance ....................... 11 Practical examples ........................................................................20 Sustainability pilots .........................................................................20 FutureBuilt, a collaboration for sustainable buildings and arenas .......20 Model projects in Asker ...................................................................20 Citizenship – evolving as a co-creation municipality ..........................24 Democratic innovation.....................................................................24 Arenas for co-creation and community work ....................................24 Policy and enabling environment ..................................................26 Engagement with the national government on SDG implementation ...26 Cooperation across municipalities and regions ................................26 Creating ownership of the Sustainable Development Goals and the VLR .......................................................................... -

Online Appendix to Political Alignment and Bureaucratic Pay

Online Appendix to Political Alignment and Bureaucratic Pay Jon H. Fiva∗ Benny Geysy Tom-Reiel Heggedalz Rune Sørensenx November 13, 2020 ∗BI Norwegian Business School, Department of Economics, Nydalsveien 37, N-0484 Oslo, Norway. E-mail: jon.h.fi[email protected] yBI Norwegian Business School, Department of Economics, Kong Christian Frederiks plass 5, N-5006 Bergen, Norway. E-mail: [email protected] zBI Norwegian Business School, Department of Economics, Nydalsveien 37, N-0484 Oslo, Norway. E-mail: [email protected] xBI Norwegian Business School, Department of Economics, Nydalsveien 37, N-0484 Oslo, Norway. E-mail: [email protected] 1 Table of contents Appendix A Principal-agent model Appendix B Supplementary figures and tables Appendix C Data sources and measurement Appendix D RD analysis of changes in council majority 2 A Principal-agent model In this section, we formally analyze how political preference alignment between a principal (politician) and an agent (CMO) affects the agent's expected pay. Preference alignment is thereby understood as a similarity along relevant preference dimensions between prin- cipal and agent (see also below). We focus on two potential underlying mechanisms. First, preference alignment gives policy-motivated agents a direct stake in achieving the public output desired by the political principal (the political mission). This is equivalent to the assumptions on policy motivation by Besley and Ghatak (2005). Second, prefer- ence alignment works to streamline communication and facilitates cooperation between contracting partners, and thereby improves the productivity of a match. This notion of productivity in a match is central to the literature on the ally principle (Bendor, Glazer and Hammond 2001; Huber and Shipan 2008; Dahlstr¨omand Holmgren 2019), and its micro-foundations { including improved communication, cooperation and control { have been extensively debated in the foregoing literature (Peters and Pierre 2004; Kopecky et al. -

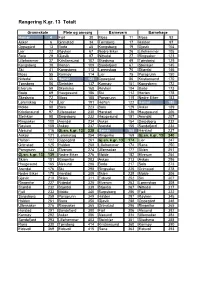

Rangering K.Gr. 13 Totalt

Rangering K.gr. 13 Totalt Grunnskole Pleie og omsorg Barnevern Barnehage Hamar 4 Fjell 30 Moss 11 Moss 92 Asker 6 Grimstad 34 Tønsberg 17 Halden 97 Oppegård 13 Bodø 45 Kongsberg 19 Gjøvik 104 Lier 22 Røyken 67 Nedre Eiker 26 Lillehammer 105 Sola 29 Gjøvik 97 Nittedal 27 Ringsaker 123 Lillehammer 37 Kristiansund 107 Skedsmo 49 Tønsberg 129 Kongsberg 38 Horten 109 Sandefjord 67 Steinkjer 145 Ski 41 Kongsberg 113 Lørenskog 70 Stjørdal 146 Moss 55 Karmøy 114 Lier 75 Porsgrunn 150 Nittedal 55 Hamar 123 Oppegård 86 Kristiansund 170 Tønsberg 56 Steinkjer 137 Karmøy 101 Kongsberg 172 Elverum 59 Skedsmo 168 Røyken 104 Bodø 173 Bodø 69 Haugesund 186 Ski 112 Horten 178 Skedsmo 72 Moss 188 Porsgrunn 115 Nedre Eiker 183 Lørenskog 74 Lier 191 Horten 122 Hamar 185 Molde 88 Sola 223 Sola 129 Asker 189 Kristiansund 97 Ullensaker 230 Harstad 136 Haugesund 206 Steinkjer 98 Sarpsborg 232 Haugesund 151 Arendal 207 Ringsaker 100 Arendal 234 Asker 154 Sarpsborg 232 Røyken 108 Askøy 237 Arendal 155 Sandefjord 234 Ålesund 116 Gj.sn. k.gr. 13 238 Hamar 168 Harstad 237 Askøy 121 Lørenskog 254 Ringerike 169 Gj.sn. k.gr. 13 240 Horten 122 Oppegård 261 Gj.sn. k.gr. 13 174 Lier 247 Grimstad 125 Halden 268 Lillehammer 174 Rana 250 Porsgrunn 133 Elverum 274 Ullensaker 177 Skien 251 Gj.sn. k.gr. 13 139 Nedre Eiker 276 Molde 182 Elverum 254 Skien 151 Ringerike 283 Askøy 213 Askøy 256 Haugesund 165 Ålesund 288 Bodø 217 Sola 273 Arendal 176 Ski 298 Ringsaker 225 Grimstad 278 Nedre Eiker 179 Harstad 309 Skien 239 Molde 306 Gjøvik 210 Skien 311 Eidsvoll 252 Ski 307 Ringerike -

Norway's 2018 Population Projections

Rapporter Reports 2018/22 • Astri Syse, Stefan Leknes, Sturla Løkken and Marianne Tønnessen Norway’s 2018 population projections Main results, methods and assumptions Reports 2018/22 Astri Syse, Stefan Leknes, Sturla Løkken and Marianne Tønnessen Norway’s 2018 population projections Main results, methods and assumptions Statistisk sentralbyrå • Statistics Norway Oslo–Kongsvinger In the series Reports, analyses and annotated statistical results are published from various surveys. Surveys include sample surveys, censuses and register-based surveys. © Statistics Norway When using material from this publication, Statistics Norway shall be quoted as the source. Published 26 June 2018 Print: Statistics Norway ISBN 978-82-537-9768-7 (printed) ISBN 978-82-537-9769-4 (electronic) ISSN 0806-2056 Symbols in tables Symbol Category not applicable . Data not available .. Data not yet available … Not for publication : Nil - Less than 0.5 of unit employed 0 Less than 0.05 of unit employed 0.0 Provisional or preliminary figure * Break in the homogeneity of a vertical series — Break in the homogeneity of a horizontal series | Decimal punctuation mark . Reports 2018/22 Norway’s 2018 population projections Preface This report presents the main results from the 2018 population projections and provides an overview of the underlying assumptions. It also describes how Statistics Norway produces the Norwegian population projections, using the BEFINN and BEFREG models. The population projections are usually published biennially. More information about the population projections is available at https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/statistikker/folkfram. Statistics Norway, June 18, 2018 Brita Bye Statistics Norway 3 Norway’s 2018 population projections Reports 2018/22 4 Statistics Norway Reports 2018/22 Norway’s 2018 population projections Abstract Lower population growth, pronounced aging in rural areas and a growing number of immigrants characterize the main results from the 2018 population projections. -

VA-Norm FELLES TEKNISKE NORMER for VANN

VA-norm FELLES TEKNISKE NORMER FOR VANN- OG AVLØPSANLEGG For kommunene Ullensaker, Nes, Eidsvoll, Hurdal og Nannestad for Aurskog Høland, Eidsvoll, Enebakk, Fet, Flateby vannverk, Gjerdrum, Hurdal, Kirkebygden og Ytre Enebakk vannverk, Lørenskog, Nannestad, Nes, Nittedal, Rælingen, Skedsmo, Sørum, Ullensaker kommuner, Årnes vannverk Anlegg for nåværende og fremtidige generasjoner Eidsvoll kommune: Vedtatt i kommunestyret 1.9.2020. Nannestad kommune: Vedtatt i kommunestyret 17.3.2020. 1-1 Desember 2019 VA-norm 1 Forord Samarbeidsprosjektet består nå av de 5 kommunene; Eidsvoll, Hurdal, Nannestad, Ullensaker Nes, samt GimilVann. Arbeidet har som mål å utarbeide en felles VA-norm som er tilpasset EU og gjeldende plan- og bygningslov. Det vil også effektivisere og kvalitetssikre utbyggingen av vann-, spillvann- og overvannsanlegg samt gi konsulenter, entreprenører og leverandører et mer forutsigbart og enhetlig regelverk for regionen. Den interkommunale normgruppa ble etablert i desember 2018 og ferdig norm forelå i desember 2019. Kontaktpersoner i kommunene: Kontaktperson Tlf.: E-post: Eidsvoll kommune Alexander Vatnehagen 92 25 48 47 [email protected] Hurdal Kommune Malin Beitdokken 90 47 28 35 [email protected] Nannestad kommune Adel Al-Jumaily 91 63 88 85 [email protected] Ullensaker kommune Terje Sandstad 94 86 08 50 [email protected] Nes kommune Ali Reza Heidari 46 24 13 14 [email protected] Normen er for alle samarbeidende kommuner/ledningseiere. VA-normen forutsettes i utgangspunktet å oppdateres annen hvert år på grunnlag av mottatte skriftlige forslag til endringer. Normen er sist revidert etter revisjonsmøte 11.12.2019. Arbeidsgruppe: Det opprettes en arbeidsgruppe på 3 personer fra kommunene/ledningseierne som har ansvar/oppgave å videreføre revisjonsarbeidet med VA-normen. -

Ruter and the Municipality of Bærum Sign Micromobility Contract with TIER

PRESS RELEASE 23 APRIL 2020 Ruter and the Municipality of Bærum sign micromobility contract with TIER TIER has been confirmed as the new supplier of micromobility solutions for the Municipality of Bærum. The municipality’s bike hire scheme will now be expanding to include electric scooters and electric bicycles. Ruter, the Public Transport Authority of Oslo and the former Akershus region, has entered into a public-public collaboration with the Municipality of Bærum. The purpose of the collaboration is to establish a wide range of mobility services for Bærum. The procurement process has now been concluded, with TIER GmbH being selected as the municipality’s supplier of micromobility solutions. – This will be the first time Ruter integrates micromobility solutions into our existing public transport system. Our collaboration with the municipality is working very well, and we believe this is going to be an important step towards the future of mobility services," says Endre Angelvik, director of mobility services at Ruter. The partnership’s plan is to integrate shared e-bikes and e-scooters into the existing public transport system – first in Lysaker, Sandvika and Fornebu in 2020, then in other parts of the municipality during springtime next year. Ruter and the municipality of Bærum intend for the new micromobility scheme to become a valuable and safe addition to the environments where they are introduced. To this end, the partnership will aim to keep in close touch with the municipality’s general population, for purposes of receiving feedback and making adjustments. Formally, the purpose of the contract is to develop a scheme that • complements existing public transport services by allowing travellers seamless movement from transport hubs all the way to their final destination • provides the aforementioned scheme to the city's inhabitants, visitors, businesses and municipal employees – Bærum is on the way towards becoming a climate-smart municipality.