Multan at the Time of Colonial Annexation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MATCH UPDATES and TIME TABLE of Pakistan Super League 2021 S.NO

MATCH UPDATES AND TIME TABLE Of Pakistan Super League 2021 S.NO. Date Time (IST) Match Venue 1. February 20 7:30 PM Karachi Kings vs National Stadium, Quetta Gladiators Karachi 2. February 21 2:30 PM Islamabad United National Stadium, v Multan Sultans Karachi 3. February 21 7:30 PM Islamabad United National Stadium, v Multan Sultans Karachi 4. February 22 7:30 PM Lahore Qalandars National Stadium, vs Quetta Karachi Gladiators 5. February 23 7:30 PM Peshawar Zalmi National Stadium, vs Multan Sultans Karachi 6 February 24 7:30 PM Karachi Kings vs National Stadium, Islamabad United Karachi 7. February 26 2:30 PM Lahore Qalandars National Stadium, vs Multan Sultans Karachi 8. February 26 7:30 PM Peshawar Zalmi National Stadium, vs Quetta Karachi Gladiators 9. February 27 2:30 PM Karachi Kings vs National Stadium, Multan Sultans Karachi 10. February 27 7:30 PM Peshawar Zalmi National Stadium, vs Islamabad Karachi United 11. February 28 7:30 PM Karachi Kings vs National Stadium, Lahore Qalandars Karachi 12. March 1 7:30 PM Islamabad United National Stadium, vs Quetta Karachi Gladiators 13. March 3 2:30 PM Karachi Kings vs National Stadium, Peshawar Zalmi Karachi 14. March 3 7:30 PM Quetta Gladiators National Stadium, vs Multan Sultans Karachi 15. March 4 7:30 PM Lahore Qalandars National Stadium, vs Islamabad Karachi United 16 March 5 7:30 PM Multan Sultans vs National Stadium, Karachi Kings Karachi 17. March 6 2:30 PM Islamabad United National Stadium, v Quetta Karachi Gladiators 18. March 6 7:30 PM Peshawar Zalmi v National Stadium, Lahore Qalandars Karachi 19. -

Consolidated List of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments

Consolidated list of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments List of HBL Branches for payments in Punjab, Sindh and Balochistan ranch Cod Branch Name Branch Address Cluster District Tehsil 0662 ATTOCK-CITY 22 & 23 A-BLOCK CHOWK BAZAR ATTOCK CITY Cluster-2 ATTOCK ATTOCK BADIN-QUAID-I-AZAM PLOT NO. A-121 & 122 QUAID-E-AZAM ROAD, FRUIT 1261 ROAD CHOWK, BADIN, DISTT. BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL TANDO GHULAM ALI 1661 MALTI, DISTT BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL MALTI, 1661 TANDO GHULAM ALI Cluster-3 Badin Badin DISTT BADIN CHISHTIAN-GHALLA SHOP NO. 38/B, KHEWAT NO. 165/165, KHATOONI NO. 115, MANDI VILLAGE & TEHSIL CHISHTIAN, DISTRICT BAHAWALNAGAR. 0105 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR KHEWAT,NO.6-KHATOONI NO.40/41-DUNGA BONGA DONGA BONGA HIGHWAY ROAD DISTT.BWN 1626 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR-TEHSIL 0677 442-Chowk Rafique shah TEHSIL BAZAR BAHAWALNAGAR Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAZAR BAHAWALPUR-GHALLA HOUSE # B-1, MODEL TOWN-B, GHALLA MANDI, TEHSIL & 0870 MANDI DISTRICT BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR Khewat #33 Khatooni #133 Hasilpur Road, opposite Bus KHAIRPUR TAMEWALI 1379 Stand, Khairpur Tamewali Distt Bahawalpur Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR KHEWAT 12, KHATOONI 31-23/21, CHAK NO.56/DB YAZMAN YAZMAN-MAIN BRANCH 0468 DISTT. BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR-SATELLITE Plot # 55/C Mouza Hamiaytian taxation # VIII-790 Satellite Town 1172 Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR TOWN Bahawalpur 0297 HAIDERABAD THALL VILL: & P.O.HAIDERABAD THAL-K/5950 BHAKKAR Cluster-2 BHAKKAR BHAKKAR KHASRA # 1113/187, KHEWAT # 159-2, KHATOONI # 503, DARYA KHAN HASHMI CHOWK, POST OFFICE, TEHSIL DARYA KHAN, 1326 DISTRICT BHAKKAR. -

Punjab Irrigated Agriculture Investment Program

Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors Sri Lanka Project Number: 37231 December 2006 Proposed Multitranche Financing Facility Islamic Republic of Pakistan: Punjab Irrigated Agriculture Investment Program CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 15 November 2006) Currency Unit – Pakistan rupee/s (PRs) PR1.00 = $0.0164 $1.00 = PRs60.8 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ADF – Asian Development Fund AWB – area water board EAF – environmental assessment framework EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental monitoring plan FFA – financial framework agreement DOFWM – Directorate of On-Farm Water Management GDP – gross domestic product GIS – geographic information system IEE – initial environmental examination IMU – irrigation management unit IPPMU – investment program planning and management unit JBIC – Japan Bank for International Cooperation LAR – land acquisition and resettlement LBDC – Lower Bari Doab Canal LBDCIP – Lower Bari Doab Canal Improvement Project LCC – Lower Chenab Canal MFF – multitranche financing facility MIS – management information system NDP – National Drainage Program O&M – operation and maintenance OFWM – on-farm water management PFR – periodic financing request PIAIP – Punjab Irrigated Agriculture Investment Program PIAPPF – Punjab irrigated agriculture project preparation facility PIDA – Punjab Irrigation and Drainage Authority PIPD – Punjab Irrigation and Power Department PISRP – Punjab Irrigation Sector Reform Program PIU – project implementation unit PMO – project management -

Orix Leasing Pakistan Limited List of Shareholders Without Cnic As on October 21, 2016

ORIX LEASING PAKISTAN LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS WITHOUT CNIC AS ON OCTOBER 21, 2016 NO. OF S. NO FOLIO NO. NAME FATHER'S \ HUSBAND'S NAME ADDRESS SHARES 5/20, DR. DATOO MANZIL, AGA KHAN ROAD 1 14 MOHAMMED MOOSA S/O MOHAMMED HUSSAIN 102 KHARADAR, KARACHI. M.R.6/13, VIRJEE STREET, JODIA BAZAR, 2 62 SH. AFZAL HUSSAIN S/O MOHD IQBAL 109 KARACHI. B-116, NEW DHORAJI COLONY, GULSHAN-E- 3 64 KHAIRUN BAI W/O MOHD IQBAL 98 IQBAL, BLOCK-4, KARACHI-47. 8, SHAH MOHD BUILDING, KIMAT RAI BHOJ 4 69 MOHD AMIN BHIMANI S/O ABDUL GHAFFAR BHIMANI 27 RAJ ROAD, ARAM BAGH, KARACHI. B-110, BLOCK-I, NORTH NAZIMABAD, 5 76 SAIFULLAH KHARI S/O MD ISHRATULLAH 658 KARACHI. C-42, BLOCK A , NORTH NAZIMABAD, 6 107 HADISUN NISA BEGUM W/O MOHAMMAD MASSOD KHAN 2,042 KARACHI. BROADWAY APPARTMENT, 2ND FLOOR FLAT 7 159 FATIMA W/O HAJI WALI MOHAMMED B-2, C-2, PLOT NO.227, STREET-16, B.M.C.H. 138 SOCIETY, SHARFABAD, KARACHI-74800. D.V. 71, USMANIA COLONY, B. ROAD, 8 340 MOHD HANIF S/O KHUDA BAKASH 138 NAZIMABAD NO.1, KARACHI. A/19-1, KHUDAD COLONY, KASHMIR ROAD, 9 344 M. A. RAOOF BAIG S/O M. REHMAT BAIG 169 KARACHI-5. 153 JINNAH COLINY MUSLIM ROAD, 10 524 TANVEER MEHRAJ S/O MEHRAJ DIN 35 SAMANABAD, LAHORE. C/O KHAWAJA TARIQ MAHMOOD, 18/B, TECH 11 525 FARZANA JABEEN D/O KH. BASHIRUDDIN 936 SOCIETY, CANAL BANK, LAHORE. HOUSE NO.18, STREET NO.35, SECTOR I-9/4, 12 526 MAHMUD AHMED S/O RIAZ AHMED 304 ISLAMABAD. -

List of Approved Clinical Trial Sites Under the Bio-Study Rules 2017

Government of Pakistan Ministry of National Health Services, Regulations & Coordination DRUG REGULATORY AUTHORITY OF PAKISTAN TF Complex, Sector G-9/4, Islamabad ****** “SAY NO TO CORRUPTION” Updated till: 09th April 2021. LIST OF APPROVED CLINICAL TRIAL SITES UNDER THE BIO-STUDY RULES 2017. S.No License Clinical Trial CTS Address Approved Study Approved Status Remarks Date of . Number Site for Drug. in C.S.C. Expiration Clinical of licence. Trial 01. CTS- M/s Holy Family Gynae Unit-I & II, Holy Women-II Tranexamic 4th CSC Approved. License issued. 17th July 0001 Hospital, Family Hospital, Said Pur Clinical Acid Meeting. 18th July 2019. 2019. Rawalpindi Road. Rawalpindi Studies. Held on 17th July 2019. 02. CTS- M/s Ghouri Plot C-76, Sector 31/5, End-TB, Multi Drug 4th CSC Approved. License issued. 09th October 0002 Clinic, The Indus Opposite Darussalam MDR TB Meeting. 10th October 2019. Hospital, Karachi Society, Korangi Crossing, Clinical Held on 17th 2019. Karachi-75190, Pakistan. Trial July 2019. 03. CTS- Aga Khan Stadium Road, P.O. Box Not Multiple 4th CSC Approved. License issued. 09th October 0003 University 3500, Karachi 74800, Specific Clinical Meeting. 10th October 2022. Hospital, Clinical Pakistan. Trials Held on 17th 2019. Trial Unit (CTU), July 2019. Karachi 04. CTS- Shaukat Khanum 7-A, Khayaban-e-Firdousi, Not Multiple 4th CSC Approved. License issued. 20th 0004 Memorial Cancer Block R3 M.A Johar Town, Specific Clinical Meeting. 21st November November Hospital & Lahore. Trials Held on 17th 2019. 2019. Research Center, July 2019. Lahore. Page 1 of 10 05. CTS- Department of Near Chandni Chowk, Women-II Tranexamic 4th CSC Approved. -

Market Monitor Report

Food Commodities Photo WFP/Aman ur Rehman khan Market Monitor Report WFP VAM | Food Security Analysis Pakistan | November 2020 HIGHLIGHTS • In October 2020, the average retail prices for wheat and wheat flour increased by 5.4% and 3.8%, respectively, while the prices of rice Irri-6 and rice Basmati increased by 0.4% and 0.1%, respectively, when compared to the previous month; • Headline inflation based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) increased in October 2020 by 1.70% over September 2020 and increased by 8.91% over October 2019; • The prices of staple cereals and non-cereal food commodities in October 2020 experienced negligible to slight fluctuations, except for live chicken and eggs which experienced significant price increases, when compared to the previous month’s prices; • In October 2020, the average ToT slightly decreased by 3.6% from the previous month; • In November 2020, the total global wheat production for 2020/21 is projected at 772.38 million MT, indicating a decrease of 0.7 million MT compared to the projection made in October 2020. Market Monitor | Pakistan | November 2020 Page 2 Headline inflation Headline inflation based on the Consumer Table 1: CPI (%) Price Index (CPI) increased in October Food Non-Food 2020 by 1.70% over September 2020 and Period Urban Rural Urban Rural increased by 8.91% over October 2019. 2020 YoY MoM YoY MoM YoY MoM YoY MoM The food/non-food values of CPI September 12.4 3.0 15.8 3.8 5.0 0.2 7.2 0.3 disaggregated at urban and rural areas is October 13.9 2.8 17.7 4.3 3.6 0.3 5.8 0.5 presented in Table 1. -

15 the Regions of Sind, Baluchistan, Multan

ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1 THE REGIONS OF SIND . 15 THE REGIONS OF SIND, BALUCHISTAN, MULTAN AND KASHMIR: THE HISTORICAL, SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC SETTING* N. A. Baloch and A. Q. Rafiqi Contents THE RULERS OF SIND, BALUCHISTAN AND MULTAN (750–1500) ....... 298 The cAbbasid period and the Fatimid interlude (mid-eighth to the end of the tenth century) ...................................... 298 The Period of the Ghaznavid and Ghurid Sultanates (eleventh and twelfth centuries) . 301 The era of the local independent states ......................... 304 KASHMIR UNDER THE SULTANS OF THE SHAH¯ MIR¯ DYNASTY ....... 310 * See Map 4, 5 and 7, pp. 430–1, 432–3, 437. 297 ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1 The cAbbasid period Part One THE RULERS OF SIND, BALUCHISTAN AND MULTAN (750–1500) (N. A. Baloch) From 750 to 1500, three phases are discernible in the political history of these regions. During the first phase, from the mid-eighth until the end of the tenth century, Sind, Baluchis- tan and Multan – with the exception of the interlude of pro-Fatimid ascendency in Mul- tan during the last quarter of the tenth century – all remained politically linked with the cAbbasid caliphate of Baghdad. (Kashmir was ruled, from the eighth century onwards, by the local, independent, originally non-Muslim dynasties, which had increasing political contacts with the Muslim rulers of Sind and Khurasan.) During the second phase – the eleventh and twelfth centuries – all these regions came within the sphere of influence of the powers based in Ghazna and Ghur. During the third phase –from the thirteenth to the early sixteenth century – they partly became dominions of the Sultanate of Delhi, which was in itself an extension into the subcontinent of the Central Asian power base. -

Report of Marketing Channel Survey (Mangoes) in Rahim Yar Khan and Multan

Policy and Institutional Reforms to Improve Horticultural Markets in Pakistan (ADP/2014/043) DRAFT REPORT 03/18 Preliminary Report of Marketing Channel Survey (Mangoes) in Rahim Yar Khan and Multan. Information Collected from Growers and Contractors. Nauman Ejaz Assistant Professor International Islamic University Islamabad [email protected] Abstract This reports preliminary results and observations on the supply chain and marketing issues including relationships between the various stakeholders (farmers, contractors, retailers, etc.), their respective profit margins and the stages through which mango flows from the farm to the consumer (marketing channels). It is based on information collected from interviews and discussions with a sample of selected mango growers and (pre-harvest) contractors in Rahim Yar Khan and Multan districts, two of the largest and most famous mango producing regions in Pakistan, during the peak mango season in July 2018. The preliminary findings suggest that the dominant system of mango marketing is the one where growers enter into pre-harvest contracts with contractors, who then sell their produce through commission agents. Often but not always entering into pre-harvest contracts and advance payment arrangements with them - and sometimes with exporters, is a stable system because it is attractive to all parties as it provides efficient methods for risk sharing and risk management. The relationships between contracting parties are informal but typically long term. But the system does not seem to provide incentives to growers to enhance quality or productivity, or acquire better skills and expertise, though there is some limited evidence of a quality premium being received by the contractors. As many growers as well as contractors consider mango as a part time occupation and a source of supplemental income, they are also unwilling to exert much effort on direct sales to wholesalers or exporters. -

The Ancient Geography of India

िव�ा �सारक मंडळ, ठाणे Title : Ancient Geography of India : I : The Buddhist Period Author : Cunningham, Alexander Publisher : London : Trubner and Co. Publication Year : 1871 Pages : 628 गणपुस्त �व�ा �सारत मंडळाच्ा “�ंथाल्” �तल्पा्गर् िनिमर्त गणपुस्क िन�म्ी वषर : 2014 गणपुस्क �मांक : 051 CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Cornell University Library DS 409.C97 The ancient geqgraphv.of India 3 1924 023 029 485 f mm Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924023029485 THE ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY ov INDIA. A ".'i.inMngVwLn-j inl^ : — THE ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY INDIA. THE BUDDHIST PERIOD, INCLUDING THE CAMPAIGNS OP ALEXANDER, AND THE TRAVELS OF HWEN-THSANG. ALEXANDER CUNNINGHAM, Ui.JOB-GBirBBALj BOYAL ENGINEEBS (BENGAL BETIBBD). " Venun et terrena demoDstratio intelligatar, Alezandri Magni vestigiiB insistamns." PHnii Hist. Nat. vi. 17. WITS TSIRTBBN MAPS. LONDON TEUBNER AND CO., 60, PATERNOSTER ROW. 1871. [All Sights reserved.'] {% A\^^ TATLOB AND CO., PEIKTEES, LITTLE QUEEN STKEET, LINCOLN'S INN EIELDS. MAJOR-Q-ENEEAL SIR H. C. RAWLINSON, K.G.B. ETC. ETC., WHO HAS HIMSELF DONE SO MUCH ^ TO THROW LIGHT ON THE ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY OP ASIA, THIS ATTEMPT TO ELUCIDATE A PARTIODLAR PORTION OF THE SUBJKcr IS DEDICATED BY HIS FRIEND, THE AUTHOR. PEEFACE. The Geography of India may be conveniently divided into a few distinct sections, each broadly named after the prevailing religious and political character of the period which it embraces, as the Brahnanical, the Buddhist^ and the Muhammadan. -

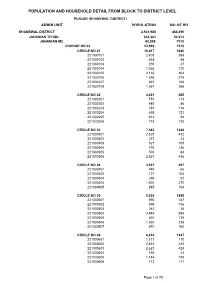

Population and Household Detail from Block to District Level

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (KHANEWAL DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH KHANEWAL DISTRICT 2,921,986 466,390 JAHANIAN TEHSIL 343,361 52,613 JAHANIAN MC 43,598 7010 CHARGE NO 03 43,598 7010 CIRCLE NO 01 10,417 1640 221030101 2,403 388 221030102 614 84 221030103 250 47 221030104 1,065 170 221030105 2,135 304 221030106 1,596 275 221030107 697 106 221030108 1,657 266 CIRCLE NO 02 4,001 655 221030201 751 113 221030202 480 86 221030203 781 116 221030204 658 121 221030205 613 94 221030206 718 125 CIRCLE NO 03 7,583 1226 221030301 2,625 432 221030302 237 43 221030303 521 105 221030304 776 126 221030305 503 84 221030306 2,921 436 CIRCLE NO 04 3,947 657 221030401 440 66 221030402 727 104 221030403 295 52 221030404 1,600 272 221030405 885 163 CIRCLE NO 05 9,034 1485 221030501 990 187 221030502 898 156 221030503 262 38 221030504 3,844 583 221030505 810 135 221030506 1,360 226 221030507 870 160 CIRCLE NO 06 8,616 1347 221030601 1,111 170 221030602 2,812 425 221030603 2,621 424 221030604 156 23 221030605 1,144 188 221030606 772 117 Page 1 of 74 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (KHANEWAL DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH JAHANIAN QH 169,785 25814 055/10-R PC 5,480 875 CHAK NO 053/10-R 1,932 337 221011403 1,124 197 221011404 700 124 221011405 108 16 CHAK NO 054/10-R 2,037 318 221011402 1,133 188 221011406 904 130 CHAK NO 055/10-R 1,511 220 221011401 1,511 220 056/10-R PC 6,093 890 CHAK NO 056/10-R 2,028 307 221011501 1,059 157 221011502 969 150 CHAK NO 057/10-R 2,786 -

Appendix - II Pakistani Banks and Their Branches (December 31, 2008)

Appendix - II Pakistani Banks and their Branches (December 31, 2008) Allied Bank Ltd. Bhalwal (2) Chishtian (2) -Grain Market -Grain Market (743) -Noor Hayat Colony -Mohar Sharif Road Abbaspur 251 RB Bandla Bheli Bhattar (A.K.) Chitral Chungpur (A.K.) Abbottabad (4) Burewala (2) Dadu -Bara Towers, Jinnahabad -Grain Market -Pineview Road -Housing Scheme Dadyal (A.K) (2) -Supply Bazar -College Road -The Mall Chak Jhumra -Samahni Ratta Cross Chak Naurang Adda Johal Chak No. 111 P Daharki Adda Nandipur Rasoolpur Chak No. 122/JB Nurpur Danna (A.K.) Bhal Chak No. 142/P Bangla Danyor Adda Pansra Manthar Darband Adda Sarai Mochiwal Chak No. 220 RB Dargai Adda Thikriwala Chak No. 272 HR Fortabbas Darhal Gaggan Ahmed Pur East Chak No. 280/JB (Dawakhri) Daroo Jabagai Kombar Akalgarh (A.K) Chak No. 34/TDA Daska Arifwala Chak No. 354 Daurandi (A.K.) Attock (Campbellpur) Chak No. 44/N.B. Deenpur Bagh (A.K) Chak No. 509 GB Deh Uddhi Bahawalnagar Chak No. 76 RB Dinga Chak No. 80 SB Bahawalpur (5) Chak No. 88/10 R Dera Ghazi Khan (2) Chak No. 89/6-R -Com. Area Sattelite Town -Azmat Road -Dubai Chowk -Model Town -Farid Gate Chakwal (2) -Ghalla Mandi -Mohra Chinna Dera Ismail Khan (3) -Settelite Town -Talagang Road -Circular Road -Commissionery Bazar Bakhar Jamali Mori Talu Chaman -Faqirani Gate (Muryali) Balagarhi Chaprar Balakot Charsadda Dhamke (Faisalabad) Baldher Chaskswari (A.K) Dhamke (Sheikhupura) Bucheke Chattar (A.K) Dhangar Bala (A.K) Chhatro (A.K.) Dheed Wal Bannu (2) Dina -Chai Bazar (Ghalla Mandi) Chichawatni (2) Dipalpur -Preedy Gate -College Road Dir Barja Jandala (A.K) -Railway Road Dunyapur Batkhela Ellahabad Behari Agla Mohra (A.K.) Chilas Eminabad More Bewal Bhagowal Faisalabad (20) Bhakkar Chiniot (2) -Akbarabad Bhaleki (Phularwan Chowk) -Muslim Bazar (Main) -Sargodha Road -Chibban Road 415 ABL -Factory Area -Zia Plaza Gt Road Islamabad (23) -Ghulam Muhammad Abad Colony Gujrat (3) -I-9 Industrial Area -Gole Cloth Market -Grand Trunk Road -Aabpara -Gole Kiryana Bazar -Rehman Saheed Road -Blue Area ABL -Gulburg Colony -Shah Daula Road. -

Regional Muslim Politics in Multan Under the British

Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences (PJSS) Vol. 34, No. 2 (2014), pp. 743-752 Regional Muslim Politics in Multan under the British Muhammad Shafique Bhatti Associate Professor, Department of History Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan Lubna Kanwal Assistant Professor, Department of Pakistan Studies Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan Email. Muhammadshafiq @ bzu.edu.pk Abstract Whether regional politics was subject to mainstream British Indian politics or was associated with the regional issues, is a major questions for the study of the History of British India. The paper evolves around the theme that regional politics under the British had been subject to Imperial structure of elites’ politics. In this structure, the regional political contests were the major reason of the change of parties or formation of political alliances. The introduction of western model of responsible representation shifted the priority area of politics from feudal to the groups and elites having a communal and mass footing. Regional politics emerged as a contest of elites having feudal decorum with those having masses temper and contacts. The success was won by those who had mass-contacts. The success of the political parties was subject to the support of those groups who had mass contacts. In the regional politics of Multan, Gillanis and Qureshis were two major contestants of Politics. Gillanis had a deep-rooted mass contact and won a mass support. The success of the Muslim League was subjects to the mass support which Gillanis has already won. Keywords: Regional Politics, Elite Politics in Multan, Politics in the British Punjab, British Multan, History of Multan I.