Preface to the Italian Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the High Court of Judicature at Bombay Criminal Appellate Jurisdiction

1 of 63 ABA.314.2019.doc IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT BOMBAY CRIMINAL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CRIMINAL ANTICIPATORY BAIL APPLICATION NO.314 OF 2019 Anand T !"#$%d & Age () *ear,& Occ.Seni/+ P+/0 ,,/+ C1ai+& B.g Data Ana!*".-,& G/a Inst."#" /0 Manage$ent& R2/.G/a Inst."#"e /0 Manage$ent& Sanque!.$& G/a-403 505. A66!.cant 7 +,#, T1e S"at /0 Maharash"+a and /"1 +, R ,6/ndent, 8ITH INTERIM APPLICATION NO.1 OF 2019 IN CRIMINAL ANTICIPATORY BAIL APPLICATION NO.314 OF 2019 T1e S"at /0 Maharash"+a A66!.cant 7 +,#, Anand Ba6#+ao T !"#$%d R ,6/ndent M+.M.1.+ Desai& Seni/+ Ad7/cat & .2%* D 7*ani 9#!:a+ni 0/+ ap6!.cant .n ABA N/.24(1 /0 2019 and 0/+ R ,6/ndent .n I.A. N/.122019. S$".A+una S. Pa.& S6 -.al P#%!.c P+/, -#"/+ 0/+ S"a" 2R ,6/ndent. D+.S1.7aj. Pawar& ACP and Inv ,".gat.ng Of0.- +. CORAM = PRA9ASH D. NAI9& J. Date /0 R , +7.ng "1e Ord + = 1)"1 D - $% + 2019 Date /0 P+/nouncing "1e Ord + = 14"1 F %+ua+* 2020 PC = 1. T1., .s an ap6!.cat./n 0/+ ant.-.6at/+* %ai! #nd + S -"./n 43) /0 C/d /0 C+.$.nal P+/-ed#+ & 19)3 >`C+.P.C@A. T1 ap6!.cant ., ::: Uploaded on - 14/02/2020 ::: Downloaded on - 14/02/2020 15:20:15 ::: 2 of 63 ABA.314.2019.doc a66+ 1end.ng a++ ," .n -/nnect./n <."1 CR N/.4 /0 201) + '.," +ed <."1 B.,1+a$%agh P/!.- S"a"./n, Pune. -

Have Playgrounds Become KOREGAONISSUE

For Private CirculationFor Private Only Circulation Only September 2020 March 2018 Mumbai PRESENTEDPRESENTED BY BY THE THE STUDENTS STUDENTS OF OF THE THE SPICE SPICE PG PG DIPLOMA DIPLOMA IN IN JOURNALISM JOURNALISM TIMELINE OF BHIMA RECORD VIRTUAL TURNOUT MARKS ABOUT THIS Have playgrounds become KOREGAONISSUE... CASE CYBER MEET ON BHIMA KOREGAON CASE NOBELNeha Solanki laureate and economist Joseph Stiglitz Team Spice Enquirer She questioned how the law allows wider polity. l Decembersaid 31,development 2017: Elgaar is Parish about- just regular groundsthem to be held in jail in spite of no Relatives now? of those arrested came ad heldtransforming to protest the the desecration lives of ore than 400 people evidence being produced, adding, up to speak movingly about their of the shrinepeople, that not commemorated just transform - logged in last Saturday “We can no longer be quiet and wait concerns for the health of their rel- Dalit icon,ing Govindeconomies. Gaikwad. In this And edi - to attend a virtual public for law to bring justice. We must atives in jail. Jenny Rowena, part- for Dalittion assertion of SPICE Enquirer, M l audit of the Bhima-Koregaon case come out and speak against this oth- ner to the latest arrest, Professor January 1, 2018: Thousands William Paul we’re exploring develop- of rioting and violence and dating erwise we will not be able to save Babu, spoke of the fear and frus- gather at Bhima Koregaon to ment across a variety of from earlylaygrounds 2018. What in Mumbai was even have our Constitution.” tration of not being able to speak to commemorate the martyrdom of more remarkable is that a simulta- “The Supreme Court Mihir Desai, also a Supreme him. -

Common Order on Cri. Bail Application Nos. 3170/18, 4552/18, 4554/18, 4555/18 & 5414/18 and Below Exh.107 in Special A.T.S

Ba:r & Bench (www.barandb,ench.com) 1 COMMON ORDER ON CRI. BAIL APPLICATION NOS. 3170/18, 4552/18, 4554/18, 4555/18 & 5414/18 AND BELOW EXH.107 IN SPECIAL A.T.S. NO.1/2018 1. These are applications for bail filed by accused No.1 Sudhir Dhavale, No.2. Rona Wilson, No.3 Surendra Gadling, No.4 Shoma Sen, No.5 Mahesh Raut and accused No.6 P. Varavara Rao, as per Section 439 of Cr.P.C. They have been charge-sheeted for commission of offences punishable under Sections 121, 121A, 124A, 153A, 505(1)(b), 117, 120B read with 34 of the Indian Penal Code, 1872 (hereinafter referred to as `I.P.C.') and under Sections 13, 16, 17, 18, 18B, 20, 38, 39, 40 of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967, as amended in 2008 and 2012 (hereinafter referred to as `UAPA'). 2. The facts of the case are inter-linked in respect of the applicants/accused, therefore, it would be proper to consider and decide bail applications of all the accused by common order. 3. The accused Nos.1 to 5 were arrested on 6/6/2018 and accused No.6 was arrested on 28/8/2018. They have been interrogated by police and remanded to judicial custody. At present, all the applicants/accused are in judicial custody. BRIEF FACTS OF THE CASE OF PROSECUTION : 4. The FIR was lodged on 8.1.2018 at Vishrambaug Police Station by one Tushar Ramesh Damgude. It was registered for commission of offences punishable under Sections 153A, 505(1)(b) and 117 read with 34 of IPC. -

Bhima Koregaon Case Hearing: Arguments by Petitioners and Respondents

BHIMA KOREGAON CASE HEARING: ARGUMENTS BY PETITIONERS AND RESPONDENTS. BY KRITIKA A & NIKITA AGARWAL The hearing on the petition Romila Thapar and Ors. vs. Union of India and Ors., known as the Bhima Koregaon case continued on September 19, 2018 at the Supreme Court heard by Chief Justice of India Deepak Misra, Justice D.Y. Chandrachud and Justice A.M. Khanwilkar. In the long arguments which lasted till 4 o’clock with a one hour lunch break, both sides—for the five plus five activists’ arrested on June 6th and August 28th in connection to Bhima Koregaon violence under FIR No. 04/2018 and the prosecution, the State of Maharashtra put forth their best arguments. Senior counsel for the activists Abhishek Manu Singhvi opened his argument by pointing towards the first FIR filed by Anita Salve, a Dalit woman and eye witness to the violence unleashed by right wing extremist groups: “Anita Salve, an eye witness to the violence of 1st January 2018, lodged FIR 2/2018 at P.S. Pimpri on 2nd January 2018, stating that violence was unleashed by a mob armed with swords, rods etc. against the Dalits and specifically names Sambhaji Bhide, Chief of Shivajinagar Pratishthan and Milind Ekbote, Chief of Hindu Janjagaran Samiti, as the perpetrators and conspirators of the attack.” He emphasised that a belated FIR was filed by Tushar Damgude, who is an Intervenor before this Court, on January 8th, eight days after the incident and seven days after the first FIR. This FIR is what is known as FIR 4/ 2018 and the raids and arrests of the activists’ have taken place under this FIR. -

Rona-Wilson-Final.Pdf

1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT MUMBAI IN ITS CRIMINAL JURISDICTION CRIMINAL WRIT PETITION NO. /2021 DISTRICT : MUMBAI IN THE MATTER OF ARTICLE 226, 227 CONSTITUTION OF INDIA AND IN THE MATTER UNDER SECTION 482 OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE CODE, 1973 AND IN THE MATTER OF ARTICLE 14, 21 AND 22 OF CONSTITUTION OF INDIA AND 2 IN THE MATTER OF CASES REGISTERED INVOKING UNLAWFUL ACTIVITIES PREVENTION ACT, 1967 AND IN THE MATTER OF INCARCERATION BY CREATING FAKE, FABRICATED DOCUMENTS IN ORDER TO FALSELY IMPLICATE PUBLIC INTELLECTUALS AND IN THE MATTER OF POLICY OF THE RESPONDENTS IN TARGETTING INTELLECTUALS BY SLAPPING CASES UNDER STRINGENT LAWS AGAINST PUBLIC JUSTICE RONA S/O JACOB WILSON ) AGED 42 YEARS, CURRENTLY ) JAILED IN CENTRAL PRISON TALOJA ) ORDINARY RESIDENT OF DELHI )... PETITIONER VERSUS 1. STATE OF MAHARASHTRA, ) THROUGH ITS ADDL. CHIEF SECRETARY, ) 3 DEPARTMENT OF HOME AFFAIRS ) HAVING HIS OFFICE AT ) MANTRALAYA MUMBAI ) 2. SHIVAJI PAWAR , AT THE MATERIAL TIME ) THE INVESTIGATING OFFICER, NOW ) HAVING HIS OFFICE AT THE OFFICE OF ) THE COMMISSIONER OF POLICE , SADHU ) VASVWANI CHOWK, CHURCH PATH, ) AGARKAR NAGAR, PUNE 411001 ) 3. UNION OF INDIA, THROUGH THE ) SECRETARY, MINISTRY OF ) HOME AFFAIRS, HAVING HIS OFFICE ) AT NORTH BLOCK NEW DELHI ) 4. NATIONAL INVESTIGATION ) AGENCY, THROUGH ITS ) SUPERINTENDENT VIKRAM ) KHALATE, HAVING HIS OFFICE AT ) CUMBALLA HILLS, PEDDAR ROAD, ) RESPONDENTS TO THE HON’BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE AND OTHER HON’BLE PUISNE JUDGES OF HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE OF BOMBAY THE HUMBLE PETITION OF THE PETITIONER -

Statement from Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) Students, Alumni and Faculty Members

Statement from Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) Students, Alumni and Faculty members We, the undersigned students, alumni, faculty, staff and other members of the TISS community stand with Mahesh Raut and the four other activists who have been arrested unfairly and demand for their immediate and unconditional release. On the morning of June 6th, 2018, the Pune Police investigating the Bhima Koregaon case arrested Mr. Mahesh Raut. Mahesh is an alumni of TISS, a former fellow at the prestigious Prime Minister’s Rural Development Programme (PMRD) and an anti-displacement activist working with gram sabhas on implementation of laws like PESA (Panchayat Extension to Scheduled Areas) and FRA (Forest Rights Act). He was arrested from Nagpur, where he had been staying for his ongoing medical treatment. On the same day, the premises of Mr. Sudhir Dhawale, Dalit activist and editor of Marathi magazine Vidrohi, Professor Shoma Sen, Head of the English literature department at Nagpur University, Advocate Surendra Gadling, general secretary of Indian Association of People’s Lawyers (IAPL), and Mr. Rona Wilson, secretary of the Committee for Release of Political Prisoners (CRPP) were raided and they were arrested too. Even as the police informed that they were being picked up in connection to the Bhima Koregaon case, the media started releasing news about them being ‘top urban Maoist operatives’. Subsequently we were also informed, again by the media, that they had been apprehended as a money trail between banned Maoist organisations and that had been discovered, in connection to funding Bhima Koregaon and the Dalit -Bahujan- Maratha- Muslim protests that ensued. -

National Alliance of People's Movements

National Alliance of People’s Movements strongly condemns the unlawful persecution and arrests of pro-people activists Shoma Sen, Advocate Surender Gadling, Sudhir Dhawale, Rona Wilson, and Mahesh Raut by the Maharashtra Police and demand for their immediate and unconditional release. New Delhi, June 8, 2018 : At around 6 am on the 6th of June, Professor Shoma Sen – Head of the English Department in Nagpur University and a long time Dalit and women’s rights activist, Advocate Surendra Gadling - General Secretary of the Indian Association of Peoples’ Lawyers (IAPL), who has been relentlessly fighting cases of human rights violations, Sudhir Dhawale - editor of the Marathi magazine Vidrohi and founder of the Republican Panther – Caste Annihilation Movement, Rona Wilson – human rights activist and Secretary of Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners (CRPP) and Mahesh Raut - anti-displacement activist working with Gram Sabhas in the mining areas of Gadchiroli and a former Prime Minister’s Rural Development Fellow – had their houses raided and were arrested from different locations in Nagpur, Bombay, and Delhi by the Maharashtra police. This was reportedly in connection with the Bhima-Koregaon agitation that took place in January 2018. Mahesh Raut has been fighting alongside local communities against State and corporate land grab, and the resultant exploitation of indigenous communities and natural resources. Adv. Gadling has been fighting out these battles in the court room and representing many Dalits and adivasis accused and arrested under false charges and draconian laws. He is also a legal counsel in the case of Dr. G.N. Saibaba, a Delhi University professor with 90% disabilities, who has been accused of having Maoist links. -

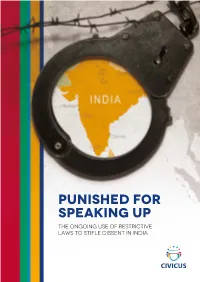

Punished for Speaking Up

PUNISHED FOR SPEAKING UP The ongoing use of restrictive laws to stifle dissent in India An Indian Student protester wearing a mask takes part in a protest demonstration during an anti-government protest against new citizenship law and recent riots on March 03, 2020 in New Delhi, India. © Yawar Nazir/ Getty Images CIVICUS is a global alliance of civil society organisations and activists dedicated to strengthening citizen action and civil society around the world. We strive to promote marginalised voices, especially from the Global South, and have members in more than 170 countries throughout the world. We believe that a healthy society is one where people have multiple opportunities to participate, come together, deliberate and act for the common good. We work for civil society, protecting and growing `civic space’ - the freedoms of expression, association and assembly - that allow citizens and organisations to speak out, organise and take action. 2 PUNISHED FOR SPEAKING UP Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ 4 THE ASSAULT ON DISSENT IN INDIA .............................................................................. 5 Judicial harassment and attacks on human rights defenders ...................................................... 5 The targeting of journalists .......................................................................................................... 5 Crackdown on protests ............................................................................................................... -

Citizens' Solidarity with Voices of Democracy

Citizens’ Solidarity with Voices of Democracy We condemn the arrest of five human rights activists, professors and lawyers in connection with the Bhima-Koregaon clashes early this year. The alarming arrest of Advocate and General Secretary of Indian Association of Peoples’ Lawyers (IAPL) Surendra Gadling, Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners (CRPP) Public Relations Secretary Rona Wilson, Head of English Department Professor Shoma Sen of Nagpur University and member of Women against Sexual Violence and State Repression (WSS), cultural activist and founder of Republican Panthers Jaatiya Antachi Chalwal Sudhir Dhawale and anti-displacement activist and Prime Ministers Rural Development Fellow (PMRDF) Mahesh Raut is a clear manifestation of state terror to crush the voices of dissent in this country. The intemperate use of sections of the IPC and Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) on all five reveals legal over-reach and exposes the desperation to foist extraordinary and excessive charges on all five to ensure they remain in the clutches of the Fadnavis-Maharashtra government. All the arrested have consistently worked for the assertion of oppressed and marginalised communities against majoritarian forces, spoken out against Brahmanical patriarchy, upheld peoples’ rights to land, life and dignity, and have strived for the release of political prisoners. Today, after standing for the assertion of dalits, adivasis, Muslims, women, workers, farmers, marginalised sexualities, and oppressed communities, upholding the principles of democracy, and, consequently, being a thorn in the side of a vengeful police force, they are under the custody of impunity. Meanwhile, the perpetrators of violence during the Bhima-Koregaon clashes enjoy the protection of the state, patronage of the RSS and walk free. -

(CRIMINAL) NO. 260 of 2018 Romila Thapar and Ors

1 REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 260 OF 2018 Romila Thapar and Ors. ….. Petitioner(s) :Versus: Union of India and Ors. ....Respondent(s) J U D G M E N T A.M. Khanwilkar, J. 1. Five illustrious persons in their own field have filed this petition on 29th August, 2018 complaining about the high- handed action of the Maharashtra Police in raiding the homes and arresting five well known human rights activists, journalists, advocates and political worker, with a view to kill independent voices differing in ideology from the party in power and to stifle the honest voice of dissent. They complain that the five activists, namely, Gautam Navalakha, Sudha Bharadwaj, Varavara Rao, Arun Ferreira and Vernon Gonsalves were arrested on 28th August, 2018 from their 2 homes at New Delhi, Faridabad, Mumbai, Thane and Hyderabad, respectively, without any credible material and evidence against them justifying their arrest, purportedly in connection with FIR No.0004/2018 dated 8th January, 2018 registered with Police Station Vishram Bagh, Pune City. This action was to silence the dissent, stop people from helping the poor and downtrodden and to instill fear in the minds of people and was a motivated action to deflect people‟s attention from real issues. The petitioners have made it clear in their petition that they were seriously concerned about the erosion of democratic values and were approaching this Court “not to stop investigation into allegations” “but” to ensure independent and credible “investigation into the arrest of stated five human rights activists.” They claim that anything short of that relief will damage the fabric of the nation irreparably. -

UAPA & Other Laws

Contents Against the Very Idea of Justice, UAPA & Other Laws Introduction 1. A Look at Repressive Laws in India 05 2. UAPA: A Brief History 42 3. Statistics: Increasing Arrests & Little Convictions 49 4. The Victims 52 5. A Law Contradicting with Indian Constitution 66 6. Need of the Hour: A United Effort 78 1. A Look at Repressive Laws in India In India, several unconstitutional laws repress its citizens1 . Indian lawmaking bodies have made, and continue to make, laws that neglect the fundamental rights of the citizens. Some laws have even blatantly violated those rights. The list of such laws, passed by both the parliament and the state legislatures, is not small. Let's have a quick look at those extraordinary, unconstitutional Indian laws (except the UAPA, which is discussed in detail later): 1.1. Sedition law (Section 124A of Indian Penal Code, 1860) 1.2. Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958 1.3. National Security Act, 1980 1.4. Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, 1987 (Amended in 1989, 1993) 1.5. Prevention of Terrorism Act, 2002 1.6. Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 1.7. The National Investigation Agency Act, 2008 1.8. Jammu & Kashmir Public Safety Act, 1978 Widespread misuse and contempt for human rights make these laws connected with each other. While some national-level anti-terror laws, like the UAPA, directly attacked the human rights of the citizens, 1https://www.epw.in/engage/article/indias-unforgivable-laws 05 Against the Very Idea of Justice the AFSPA, a law active only in a few states, did the same with giving chilling impunity to armed forces involved in different forms of violence, including extrajudicial killings. -

India's Covid Crisis: Can the Modi Regime Get India out Of

India’s Covid Crisis: Can the Modi Regime Get India Out of It? It’s hard to live in India these days, surrounded by death, fear and grief. We are inundated with heart-breaking TV reports of people begging for hospital beds and oxygen as their family members die on the pavement or in vehicles gasping for breath. Others die inside hospitals as they run out of oxygen. Equally disturbing are reports of crematorium and burial ground staff working 24/7 and still unable to get through the huge number of corpses, so that extra pyres have to be set up in parks and car parks; the massive discrepancy between those who are cremated or buried under Covid protocols and the official figures is explained by the fact that officials have been told not to write ‘Covid-19’ as the cause of death, suggesting to some experts that the real death toll may be 2 to 5 times higher than the reported figure.[1] Other medical experts say the death toll could be up to 10 times the official one.[2] Let’s spell this out, for the sake of clarity. Twice the official death count of over 250,000 would bring it to 500,000 deaths, five times would bring it to 1.25 million, while 10 times would bring it up to 2.5 million. And since the cases are similarly undercounted due to the lack of testing, they too are probably the highest in the world. These images from major cities have been flashed around the world, but what is happening in villages is even more terrifying.