The Generic Allocation of the Green-Tailed Towhee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS of SONG and RESPONSES to SONG PLAYBACK University of Colorado at Denver

FINAL REPORT A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF SONG AND RESPONSES TO SONG PLAYBACK IN THE AVIAN GENUS PIPILO Peter S. Kaplan Department of Psychology University of Colorado at Denver Abstract An experiment was undertaken to characterize the responses of Green-tailed Towhees (Pipilo chlorura) and Rufous-sided Towhees (P. erythophthalmus) to each others' songs and to the songs of five other towhee species, plus one hybrid form. A total of 12 Green-Tailed Towhees and 10 Rufous-sided Towhees from Boulder and Gilpin counties were studied at three field sites: the Doudy Draw Trail, the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), and on private land at the mouth of Coal Creek Canyon. In May, each bird was mist-netted and banded to facilitate individual identification. During the subsequent playback phase in June and July, each individual received one three-part playback trial on each of 7 consecutive or near-consecutive days. A 9-min playback trial consisted of a 3-min "pre-play" period, during which the bird was observed in the absence of song playback, a 3-min "play" period, in which tape recorded song was played to the subject from a central point in his territory, and a 3-min "post-play" period when the bird • was again observed in the absence of song playback. Order of presentation of song exemplars from different towhee species were randomized across birds. The main dependent measure was the change in the number of songs produced by the subject bird during song playback, relative to the pre-play period. Results showed that Green-tailed Towhees responded by significantly increasing their rate of singing, but only in response to Green-tailed Towhee songs. -

Voice in Communication and Relationships Among Brown Towhees

THE CONDOR VOLUME 66 SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER, 1964 NUMBER 5 VOICE IN COMMUNICATION AND RELATIONSHIPS AMONG BROWN TOWHEES By JOET.MARSHALL,JR. This paper seeks to answer two questions: (1) What is the function of each song and call in brown towhees; that is, what information does a bird communicate to its fellows vocally, o’r how does it regulate their behavior by its voice? (2) What evi- dence does voice offer for understanding relationship by descent within the closely-knit group of brown towhee species? For the first, I would extend the analysis of Quain- tance (1938,194l) to all members of the group. As to the second question, an ingenious evolutionary reconstruction, based on museum and habitat studies, has been developed by Davis (1951). Do vocal attributes agree with his scheme? The three speciesof brown towhees, genus Pipdo, are the same size and general color and are more similar to each other than any one of them is to other ground-inhabiting finches in the same genus and in the genus Melozorte. Indeed, so close is their relation- ship that the same calls can easily be discerned in each species; although differing in timbre, similarity in form and usage proclaims them to be homologous. The Abert Towhee (Pipdo abed) occupies dense riparian woodland and mesquite thickets of the Colorado River and Gila River drainages, mostly in Arizona. The Brown Towhee proper (Pip20 fuscus) lives in brushy margins of openings in the southwestern United States and Mexico. The White-throated Towhee (Pipilo aZbicoZZis)inhabits brushy slopes, often with tree yuccas, in Puebla and Oaxaca, MCxico. -

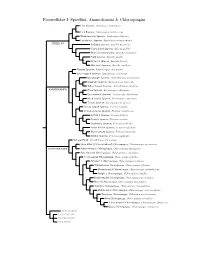

Passerellidae Species Tree

Passerellidae I: Spizellini, Ammodramini & Chlorospingini Lark Sparrow, Chondestes grammacus Lark Bunting, Calamospiza melanocorys Black-throated Sparrow, Amphispiza bilineata Five-striped Sparrow, Amphispiza quinquestriata SPIZELLINI Chipping Sparrow, Spizella passerina Clay-colored Sparrow, Spizella pallida Black-chinned Sparrow, Spizella atrogularis Field Sparrow, Spizella pusilla Brewer’s Sparrow, Spizella breweri Worthen’s Sparrow, Spizella wortheni Tumbes Sparrow, Rhynchospiza stolzmanni Stripe-capped Sparrow, Rhynchospiza strigiceps Grasshopper Sparrow, Ammodramus savannarum Grassland Sparrow, Ammodramus humeralis Yellow-browed Sparrow, Ammodramus aurifrons AMMODRAMINI Olive Sparrow, Arremonops rufivirgatus Green-backed Sparrow, Arremonops chloronotus Black-striped Sparrow, Arremonops conirostris Tocuyo Sparrow, Arremonops tocuyensis Rufous-winged Sparrow, Peucaea carpalis Cinnamon-tailed Sparrow, Peucaea sumichrasti Botteri’s Sparrow, Peucaea botterii Cassin’s Sparrow, Peucaea cassinii Bachman’s Sparrow, Peucaea aestivalis Stripe-headed Sparrow, Peucaea ruficauda Black-chested Sparrow, Peucaea humeralis Bridled Sparrow, Peucaea mystacalis Tanager Finch, Oreothraupis arremonops Short-billed (Yellow-whiskered) Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus parvirostris CHLOROSPINGINI Yellow-throated Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus flavigularis Ashy-throated Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus canigularis Sooty-capped Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus pileatus Wetmore’s Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus wetmorei White-fronted Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus albifrons Brown-headed -

Conservation of Biodiversity in México: Ecoregions, Sites

https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/281359459_DRAFT_Conservation_of_biodiversity_in_Mexico_ecoregions_sites_a nd_conservation_targets_Synthesis_of_identification_and_priority_setting_exercises_092000_ -_BORRADOR_Conservacion_de_la_biodiversidad_en_ CONSERVATION OF BIODIVERSITY IN MÉXICO: ECOREGIONS, SITES AND CONSERVATION TARGETS SYNTHESIS OF IDENTIFICATION AND PRIORITY SETTING EXERCISES DRAFT Juan E. Bezaury Creel, Robert W. Waller, Leonardo Sotomayor, Xiaojun Li, Susan Anderson , Roger Sayre, Brian Houseal The Nature Conservancy Mexico Division and Conservation Science and Stewardship September 2000 With support from the United States Agency for Internacional Development (USAID) through the Parks in Peril Program and the Goldman Fund ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dra. Laura Arraiga Cabrera - CONABIO Mike Beck - The Nature Conservancy Mercedes Bezaury Díaz - George Mason High School Tim Boucher - The Nature Conservancy Eduardo Carrera - Ducks Unlimited de México A.C. Dr. Gonzalo Castro - The World Bank Dr. Gerardo Ceballos- Instituto de Ecología UNAM Jim Corven - Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences / WHSRN Patricia Díaz de Bezaury Dr. Exequiel Ezcurra - San Diego Museum of Natural History Dr. Arturo Gómez Pompa - University of California, Riverside Larry Gorenflo - The Nature Conservancy Biol. David Gutierrez Carbonell - Comisión Nal. de Áreas Naturales Protegidas Twig Johnson - World Wildlife Fund Joe Keenan - The Nature Conservancy Danny Kwan - The Nature Conservancy / Wings of the Americas Program Heidi Luquer - Association of State Wetland -

Avian Survey Report

Spring/Summer 2010 Avian Survey Report Stony Creek Wind Farm Wyoming County, New York January 24, 2011 PREPARED FOR: Stony Creek Energy LLC 51 Monroe St. Suite 1604 Rockville, MD 20850 PREPARED BY: Lackawanna Executive Park 239 Main Street, Suite 301 Dickson City, PA 18519 www.shoenerenvironmental.com Stony Creek Wind Farm Avian Survey January 24, 2011 Table of Contents I. Summary and Background .................................................................................................1 Summary .......................................................................................................................1 Project Description ........................................................................................................1 Project Review Background ..........................................................................................2 II. Bald Eagle Survey .............................................................................................................3 Bald Eagle Breeding Status in New York ......................................................................3 Daily Movements of Bald Eagle in New York ...............................................................4 Bald Eagle Conservation Status in New York ................................................................4 Bald Eagle Survey Method ............................................................................................5 Analysis of Bald Eagle Survey Data ..............................................................................6 -

CRSQ Volume 15

CREATION RESEARCH SOCIETY QUARTERLY Copyright 1978 0 by Creation Research Society VOLUME 15 JUNE, 1978 NUMBER 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL BOARD Page Accurate Predictions can be Harold L. Armstrong, Editor Made on the Basis of Biblical 4 Couper Street Creation Concepts . 3 Kingston, Ontario, Canada Walter E. Lammerts Walter E. Lammerts, Research Editor A (Recently) Living Plesiosaur Found? . 8 Ralph Swanson Donald 0. Acrey . Geophysicist, Amarillo, Texas Thomas G. Barnes . University of Texas at El Paso, Texas More Recent Stalactites . 8 John Amer Duane T. Gish . Institute for Creation Research, San Diego, Calif. Rapid Stalactite Formation Observed . 9 George F. Howe . Los Angeles Baptist College, Eric B. Cannell Newhall, Calif. Creation, Evolution and Catastrophism . 12 John W. Klotz . Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, MO. James E. Strickling John N. Moore . Michigan State University East Lansing, Michigan Creationist Predictions Involving Cl4 Dating . ............ 14 Henry M. Morris . Institute for Creation Research, Don B. DeYoung San Diego, Calif. William J. Tinkle . Anderson College (retired) Radiocarbon Calibration-Revised. ............ 16 North Manchester, Indiana David J. Tyler John C. Whitcomb. Grace Theological Seminary, Dendrochronology, Radiocarbon, Winona Lake, Ind. and Bristlecones . 24 Emmett Williams . Bob Jones University, Harold S. Gladwin Greenville, S. Car. The Canopy and Ancient Longevity. 27 Notices of change of address, and failure to receive this publication Joseph C. Dillow should be sent to Wilbert H. Rusch, Sr. 27 17 Cranbrook Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48 104. Life Begins at 140 . 34 Creation Research Society Quarterly is published by the Creation Captain Geoffrey T. Whitehouse Research Society, 2717 Cranbrook Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104. -

LSNY Proceedings 74, 1977-1995

II >77 74 Proceedings ; 99 of ^Linnaean Society of New York ' 977~ l 995 On the cover: Selected examples of 77 specimens from the hybrid Collared/Spotted towhee (Pipilo ocai/maculatus) population of Cerro Viejo, Jalisco, Mexico. 1 hese eight specimens include the two extremes in the sample and some typical intermediate examples. See Charles G. Sibley, Hybridization in the Red-eyed Towhees of Mexico, page 6. Proceedings of the Linnaean Society of New York Figures i a and i b. Typical examples ofthe two species of red-eyed towhees ofMexico: upper, Pipilo ocai, Collared Towhee, lower, Pipilo maculatus, Spotted Towhee. Proceedings of ^Linnaean Society of New York The Linnaean Society of New York The Linnaean Society of New York, organized in 1 878, is the second oldest of existing Ameri- can ornithological societies. Regular meetings of the Society are held on the second and fourth Tuesdays of each month from September through May. The Annual Dinner, followed by the Annual Meeting and Election of Officers, is held during the second week of March. Informal summer meetings are held on the third Tuesday of each month from June through August. All meetings are open to the public and are held at the American Museum of Natural History. Persons interested in natural history are eligible for election to membership in the Society. The Society' conducts field trips and maintains a library for its members. It disu ibutes free to all members a monthly News-Letter and, at irregular intervals, an issue of Proceedings contain- ing longer articles, general notes, and annual reports of the activities of the Society’. -

WOS-AFO 2009 Program Final Complete

PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS WILSON ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY AND ASSOCIATION OF FIELD ORNITHOLOGISTS JOINT MEETING – 2009 08-12 April 2009 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Program and Abstracts 2009 WOS-AFO Meeting Thursday, 9 April 06:00AM – 8:00AM – Local birding trips (Three Rivers Bird Club coordinates) 08:00AM – 7:00PM – Registration Open 09:00AM – 5:00PM – WOS Council Meeting – Rivers Room 09:00AM – 5:00PM – AFO Council Meeting – Brigade Room 1:00PM – 5:00PM – Workshop on IACUC and Animal Care - Coffee breaks 10:30AM and 3:00PM 6:00PM – 8:00PM – Icebreaker social at Hilton Pittsburgh 8:00PM – 11:00PM – Hospitality Suite open at Hilton Pittsburgh Friday, 10 April 06:00AM – 8:00AM – Local birding trips (Three Rivers Bird Club coordinates) 07:00AM – 8:30AM – Hospitality Suite open at Hilton Pittsburgh 08:00AM – 7:00PM – Registration Open 08:00AM – 8:30AM – Welcome Grand Ballroom Room 3/4 National Aviary – Todd Katzner WOS – Jim Rising AFO – David Bonter 08:30AM – 09:30AM – AFO Plenary Lecture, Grand Ballroom Room 3/4 – Dr. Bruce M. Beehler, The Forgotten Science—A Role for Natural History in the 21 st Century 09:30AM – 10:00AM – Break – Ballroom Foyer 10:00AM – 12:00PM – Concurrent Paper Sessions, Grand Ballroom Room 3 & Room 4 11:30AM – 12:00PM – Meet the editors, Grand Ballroom Room 3 Clait Braun, Editor, Wilson Journal of Ornithology Gary Ritchison, Editor, Journal of Field Ornithology 12:00PM – 1:00PM – Lunch Break 12:00PM – 1:00PM – Hospitality Suite open at Hilton Pittsburgh 1:00PM – 2:00PM – Joint WOS/AFO Business Meeting Grand Ballroom Room -

Featured Photo Putative Canyon Towhee × Spotted Towhee: a New Intergeneric Hybrid

FEATURED PHOTO PUTATIVE CANYON TOWHEE × SPOTTED TOWHEE: A NEW INTERGENERIC HYBRID DAVID TØNNESSEN, 5230 Sevenoaks Drive, Colorado Springs, Colorado 80919; [email protected] At an elevation of 1800 m on the outskirts of Colorado Springs, Colorado, among iron-rich hillsides laden with mixed piñon–juniper woodland and Gambel’s oak thickets where Spotted Towhees (Pipilo maculatus) breed densely, a small popula- tion of the Canyon Towhee (Melozone fusca) also resides. Along with scattered pockets of the species elsewhere in El Paso County, this population in Red Rock Canyon Open Space represents the northernmost site for the Canyon Towhee. The Canyon Towhee has been increasing in numbers and spreading slowly northward from its historic range in southeastern Colorado (B. Maynard pers. comm). In the fall of 2019, I documented an occurrence that might be characteristic of such edges of species’ ranges. On 21 and 22 November 2019 I photographed an interesting towhee in good light and from many angles (Figures 1–3). Colored overall like the Canyon Towhees it was feeding with, this individual stood out because of its smaller size, timid be- havior, and odd dark smudges throughout the plumage. From its external features and behavior, I concluded that this bird was a Canyon Towhee × Spotted Towhee (Melozone fusca × Pipilo maculatus) and so the first known hybrid between the genera Melozone and Pipilo. This individual resembled a Canyon Towhee in its rufous crown and overall tannish coloration, but several plumage oddities ruled out a pure individual of that species. A charred tinge characterized the upperparts, where the mantle showed a slightly streaked pattern, while the flanks were slightly brighter and buffy. -

2020 Southern Mexico Species List

BIRD CHECKLIST Guides: Eagle-Eye Tours 2020 Southern Mexico Hector Gomez de Silva Steve Ogle Southern Mexico Seen/ No. Common Name Latin Name Heard TINAMOUS 1 Slaty-breasted Tinamou Crypturellus boucardi h 2 Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui h DUCKS, GEESE, AND WATERFOWL 3 Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor s 4 Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis s 5 Blue-winged Teal Anas (Spatula) discors s 6 Northern Pintail Anas acuta s 7 Green-winged Teal Anas crecca s 8 Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris s 9 Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis s GUANS, CHACHALACAS, AND CURASSOWS 10 Highland Guan Penelopina nigra h 11 Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula h 12 West Mexican Chachalaca Ortalis poliocephala s 13 White-bellied Chachalaca Ortalis leucogastra s NEW WORLD QUAIL 14 Long-tailed Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx macroura s GREBES 15 Least Grebe Tachybaptus dominicus s STORKS 16 Jabiru Jabiru mycteria s 17 Wood Stork Mycteria americana s FRIGATEBIRDS 18 Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens s CORMORANTS AND SHAGS 19 Neotropic Cormorant Phalacrocorax brasilianus s ANHINGAS 20 Anhinga Anhinga anhinga s PELICANS 21 American White Pelican Pelecanus erythrorhynchos s 22 Brown Pelican Pelecanus occidentalis s HERONS, EGRETS, AND BITTERNS 23 Pinnated Bittern Botaurus pinnatus s 24 Bare-throated Tiger-Heron Tigrisoma mexicanum s 25 Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias s 26 Great Egret Ardea alba s 27 Snowy Egret Egretta thula s 28 Little Blue Heron Egretta caerulea s 29 Tricolored Heron Egretta tricolor s 30 Reddish Egret Egretta rufescens s 31 Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis s 32 Green Heron Butorides virescens s 33 Black-crowned Night-Heron Nycticorax nycticorax s Page 1 of 16 BIRD CHECKLIST Guides: Eagle-Eye Tours 2020 Southern Mexico Hector Gomez de Silva Steve Ogle Southern Mexico Seen/ No. -

Printable PDF Format

Field Guides Tour Report Christmas in Oaxaca 2019 Dec 21, 2019 to Dec 28, 2019 Doug Gochfeld, Micah Riegner and Jorge Montejo For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. One of the biggest avian attractions of Oaxaca is the glowing red, silver-cheeked Red Warbler. Photo by guide Doug Gochfeld. Oaxaca, land of the Zapotecas, is a place all birders should go—its magic is not just in the birds, (and don’t get me wrong, the birding’s great) but in the vibrant culture, deep history, colorful rugs and distinct flavors that make Oaxaca, well, Oaxaca. Our Christmas tour landed numerous avian highlights from the flocks of Dwarf Jays that dazzled us in the moss-laden hardwoods of Cerro San Felipe to the Russet-crowned Motmots backdropped by columnar cacti along KM 77, the flock of Elegant Euphonias frantically flitting through mistletoe, and the crepuscular chorus of Fulvous Owls that chilly night in the mountains. For cultural activities we visited several important historical sites, like Mitla and Monte Alban, had dinner overlooking the bustling Zocalo, and watched the rug making demonstration by the Mendoza sisters, a Field Guides tradition that goes back many years. Day one, we worked the slope above Teotitlan del Valle, starting in the arid shrublands where we saw numerous sparrows, the endemic Boucard’s Wren, and our first Gray-fronted Woodpeckers. The reservoir above town had numerous Least Grebes, a Green Kingfisher and some Blue-winged Teal. After some nice views of Black-vented Orioles and Greenish Elaenia, we ascended into the Oak zone, to see Mexican Violetears, Mountain Trogon, a smattering of western warblers and Gray-collared Becard. -

Western Birds

WESTERN BIRDS Vol. 51, No. 3, 2020 Western Specialty: McKay’s Bunting Photo by Rachel Richardson of Anchorage, Alaska: McKay’s Bunting (Plectrophenax hyperboreus), St. Matthew Island, Alaska, 30 June 2018. In this issue of Western Birds, Jack Withrow explores plumage variation in the buntings Photo by Andrew Spencer of Ithaca, New York: of the genus Plectrophenax and suggests that McKay’s Bunting is a subspecies of Snow Cinereous Owl (Strix sartorii), Rancho la Noria, Sierra de San Juan, Bunting (P. nivalis) instead of a biological species. This female McKay’s Bunting shows Nayarit, Mexico, 5 June 2015. the broad white edges to the primaries, alula, and tertials, along with primary coverts that After searching six of the nine areas where the Cinereous Owl had been are dark for their entire length, that help to distinguish it from a male Snow Bunting at this collected in the 19th and 20th centuries, as well as four additional sites, season. On the basis of the faded primaries it may be a one-year-old bird. Note how a black Nathan Pieplow, Andrew Spencer, Carlos Sanchez, and Manuel Grosselet and white bird can blend in well with the lichens on its preferred nesting substrate of rocky found it at only one, as they report in this issue of Western Birds. In the talus. 21st century this species endemic to mainland Mexico has been reported from only two localities, implying a steep decline. Most of its habitat of pine–oak forest has been destroyed or degraded, and the Cinereous Owl may be seriously endangered.