Criminal Law: Malicious Damage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 8 Criminal Conduct Offences

Chapter 8 Criminal conduct offences Page Index 1-8-1 Introduction 1-8-2 Chapter structure 1-8-2 Transitional guidance 1-8-2 Criminal conduct - section 42 – Armed Forces Act 2006 1-8-5 Violence offences 1-8-6 Common assault and battery - section 39 Criminal Justice Act 1988 1-8-6 Assault occasioning actual bodily harm - section 47 Offences against the Persons Act 1861 1-8-11 Possession in public place of offensive weapon - section 1 Prevention of Crime Act 1953 1-8-15 Possession in public place of point or blade - section 139 Criminal Justice Act 1988 1-8-17 Dishonesty offences 1-8-20 Theft - section 1 Theft Act 1968 1-8-20 Taking a motor vehicle or other conveyance without authority - section 12 Theft Act 1968 1-8-25 Making off without payment - section 3 Theft Act 1978 1-8-29 Abstraction of electricity - section 13 Theft Act 1968 1-8-31 Dishonestly obtaining electronic communications services – section 125 Communications Act 2003 1-8-32 Possession or supply of apparatus which may be used for obtaining an electronic communications service - section 126 Communications Act 2003 1-8-34 Fraud - section 1 Fraud Act 2006 1-8-37 Dishonestly obtaining services - section 11 Fraud Act 2006 1-8-41 Miscellaneous offences 1-8-44 Unlawful possession of a controlled drug - section 5 Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 1-8-44 Criminal damage - section 1 Criminal Damage Act 1971 1-8-47 Interference with vehicles - section 9 Criminal Attempts Act 1981 1-8-51 Road traffic offences 1-8-53 Careless and inconsiderate driving - section 3 Road Traffic Act 1988 1-8-53 Driving -

Double Jeopardy

The Law Commission Consultation Paper No 156 DOUBLE JEOPARDY A Consultation Paper The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Law Commissioners are: The Honourable Mr Justice Carnwath CVO, Chairman Miss Diana Faber Mr Charles Harpum Mr Stephen Silber, QC When this consultation paper was completed on 6 September 1999, Professor Andrew Burrows was also a Commissioner. The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Sayers and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London WC1N 2BQ. This consultation paper is circulated for comment and criticism only. It does not represent the final views of the Law Commission. The Law Commission would be grateful for comments on this consultation paper before 31 January 2000. All correspondence should be addressed to: Mr R Percival Law Commission Conquest House 37-38 John Street Theobalds Road London WC1N 2BQ Tel: (020) 7453-1232 Fax: (020) 7453-1297 It may be helpful for the Law Commission, either in discussion with others concerned or in any subsequent recommendations, to be able to refer to and attribute comments submitted in response to this consultation paper. Any request to treat all, or part, of a response in confidence will, of course, be respected, but if no such request is made the Law Commission will assume that the response is not intended to be confidential. The text of this consultation paper is available on the Internet at: http://www.open.gov.uk/lawcomm/ Comments can be sent by e-mail to: [email protected] 17-24-01 THE LAW COMMISSION DOUBLE JEOPARDY CONTENTS [PLEASE NOTE: The pagination in this Internet version varies slightly from the hard copy published version. -

Concealment of Birth: Time to Repeal a 200-Year-Old “Convenient Stop-Gap”?

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk Faculty of Arts and Humanities School of Society and Culture 2019-07 Concealment of Birth: Time to Repeal a 200-Year-Old "Convenient Stop-Gap"? Milne, E http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/15651 10.1007/s10691-019-09401-6 Feminist Legal Studies Springer Science and Business Media LLC All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. Concealment of birth: time to repeal a 200-year-old “convenient stop-gap”? Introduction The criminal offence of concealment of birth (concealment) prohibits the secret disposal of the dead body of a child in order to conceal knowledge of that child’s birth under English and Welsh criminal law.1 Most prosecutions are of women who have concealed or denied their pregnancy, then given birth alone, with the child dying around the time of birth, and the woman disposing of the body without informing another person of the existence of the child. The offence is closely connected to newborn infant homicide and defendants are often suspected of being responsible for the child’s death. While the offence can be committed by anyone, the defendant is most often the birth mother.2 The offence is rarely prosecuted with only four convictions between 2010 and 2014 (Milne 2017), and since 2002 only one person has received an immediate custodial sentence.3 However, despite the small number of convictions and nature of the sentence, the offence is significant, particularly when analysed from a feminist perspective. -

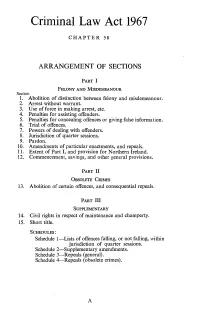

Criminal Law Act 1967 (C

Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. 58) 1 SCHEDULE 4 – Repeals (Obsolete Crimes) Document Generated: 2021-04-04 Status: This version of this schedule contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967, SCHEDULE 4. (See end of Document for details) SCHEDULES SCHEDULE 4 Section 13. REPEALS (OBSOLETE CRIMES) Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 The text of S. 10(2), S. 13(2), Sch. 2 paras. 3, 4, 6, 10, 12(2), 13(1)(a)(c)(d), 14, Sch. 3 and Sch. 4 is in the form in which it was originally enacted: it was not reproduced in Statutes in Force and does not reflect any amendments or repeals which may have been made prior to 1.2.1991. PART I ACTS CREATING OFFENCES TO BE ABOLISHED Chapter Short Title Extent of Repeal 3 Edw. 1. The Statute of Westminster Chapter 25. the First. (Statutes of uncertain date — Statutum de Conspiratoribus. The whole Act. 20 Edw. 1). 28 Edw. 1. c. 11. (Champerty). The whole Chapter. 1 Edw. 3. Stat. 2 c. 14. (Maintenance). The whole Chapter. 1 Ric. 2. c. 4. (Maintenance) The whole Chapter. 16 Ric. 2. c. 5. The Statute of Praemunire The whole Chapter (this repeal extending to Northern Ireland). 24 Hen. 8. c. 12. The Ecclesiastical Appeals Section 2. Act 1532. Section 4, so far as unrepealed. 25 Hen. 8. c. 19. The Submission of the Clergy Section 5. Act 1533. The Appointment of Bishops Section 6. Act 1533. 25 Hen. 8. c. -

PDF the Whole

Status: Point in time view as at 01/02/1991. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Indictments Act 1915. (See end of Document for details) Indictments Act 1915 1915 CHAPTER 90 5 and 6 Geo 5 An Act to amend the Law relating to Indictments in Criminal Cases, and matters incidental or similar thereto. [23rd December 1915] 1 Rules as to indictments. The rules contained in the First Schedule to this Act with respect to indictments shall have effect as if enacted in this Act, but those rules may be added to, varied, or annulled by further rules made . F1 under this Act. Textual Amendments F1 Words repealed by Criminal Justice Administration Act 1956 (c. 34), s. 19(4)(b) 2 Powers of rule committee. (1) . F2 (2) The [F3Crown Court rule committee] shall have power from time to time, . F4 to make rules varying or annulling the rules contained in the First Schedule to this Act and to make further rules with respect to the matters dealt with in those rules, and those rules shall have effect subject to any modifications or additions so made. (3) . F5 (4) . F6 Textual Amendments F2 S. 2(1) repealed by Criminal Justice Administration Act 1956 (c. 34), s. 19(4)(b) F3 Words substituted by virtue of Courts Act 1971 (c. 23), Sch. 8 para. 17(1) but not so as to invalidate any rules previously made F4 Words repealed by Criminal Justice Administration Act 1956 (c. 34), s. 19(4)(b) F5 S. 2(3) repealed by Courts Act 1971 (c. -

Indictments Act, 1915. [55& 6 GEO

Indictments Act, 1915. [55& 6 GEO. 5. CH. 90.] SOUT PLI- FOR THE , ) ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS. A.D. 1915. Section. 1. Rules as to indictments. 2. Powers of rule committee. 3. General provisions as to indictments. 4. Joinder of charges in the same indictment. 5. Orders for amendment of indictment, separate trial, and postponement of trial. 6. Costs of defective or redundant indictments. 7. Provision as to Vexatious Indictments Acts. 8. Savings and interpretation. 9. Repeal, extent, short title, and commencement. SCHEDULES. [5 & 6 GEO. 5.] Indictments Act, 1915. [CH. 90.] CHAPTER 90. An' Act to amend the Law relating to Indictments in A.D. 1915. Criminal Cases, and matters incidental or similar thereto. - [23rd December 1915.1 it enacted by the King's most Excellent Majesty, by and BEwith the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows : 1. The rules contained in the First Schedule to. this Act With Rules as to respect to indictments shall have effect as if enacted in this Act, indictments. but those rules may be added to, varied, or annulled by further rules made by the rule committee under this Act. 2.-(1) There shall be established for the purposes of this Powers of rule Act a rule committee consisting of the Lord Chief Justice of committee. England for the time being, and of a judge of the High Court, a chairman of quarter sessions, a recorder, a clerk of assize, a clerk of the peace, and another person having experience in criminal procedure, appointed in each case by the Lord Chief Justice. -

Violence Against the Person

Home Office Counting Rules for Recorded Crime With effect from April 2021 Violence against the Person Homicide Death or Serious Injury – Unlawful Driving Violence with injury Violence without injury Stalking and Harassment All Counting Rules enquiries should be directed to the Force Crime Registrar Home Office Counting Rules for Recorded Crime With effect from April 2021 Homicide Classification Rules and Guidance 1 Murder 4/1 Manslaughter 4/10 Corporate Manslaughter 4/2 Infanticide All Counting Rules enquiries should be directed to the Force Crime Registrar Home Office Counting Rules for Recorded Crime With effect from April 2021 Homicide – Classification Rules and Guidance (1 of 1) Classification: Diminished Responsibility Manslaughter Homicide Act 1957 Sec 2 These crimes should not be counted separately as they will already have been counted as murder (class 1). Coverage Murder Only the Common Law definition applies to recorded crime. Sections 9 and 10 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861 give English courts jurisdiction where murders are committed abroad, but these crimes should not be included in recorded crime. Manslaughter Only the Common Law and Offences against the Person Act 1861 definitions apply to recorded crime. Sections 9 and 10 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861 gives courts jurisdiction where manslaughters are committed abroad, but these crimes should not be included in recorded crime. Legal Definitions Corporate Manslaughter and Homicide Act 2007 Sec 1(1) “1 The offence (1) An organisation to which this section applies is guilty of an offence if the way in which its activities are managed or organised - (a) causes a person’s death, and (b) amounts to a gross breach of a relevant duty of care owed by the organisation to the deceased.” Capable of Being Born Alive - Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929 Capable of being born alive means capable of being born alive at the time the act was done. -

Arrangement of Sections

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART 11 OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES: Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH n , 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] E IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and BTemporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are J\b<?liti?n of hereby abolished. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967. (See end of Document for details) Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Annotations: Extent Information E1 Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1 Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2) Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12 Arrest without warrant. (1) The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by 2 Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. -

Cases and Materials on Criminal Law

Cases and Materials on Criminal Law Michael T Molan Head ofthe Division ofLaw South Bank University Graeme Broadbent Senior Lecturer in Law Bournemouth University PETMAN PUBLISHING Contents Preface ix Acknowledgements x Table ofcases xi Table of Statutes xxiii 1 External elements of liability 1 Proof - Woolmington v DPP - Criminal Appeal Act 1968 - The nature of external elements - R v Deller - Larsonneur - Liability for omissions - R v Instan - R v Stone and Dobinson - Fagan v Metropolitan Police Commissioner - R v Miller - R v Speck - Causation in law -Äv Pagett - Medical treatment - R v Sw/YA - R v Cheshire - The victim's reaction as a «ovtt.j öcto interveniens — Rv Blaue - R v Williams 2 Fault 21 Intention -Äv Hancock and Shankland - R v Nedrick - Criminal Justice Act 1967 s.8 - Recklessness -fiv Cunningham - R v Caldwell - R v Lawrence - Elliott \ C -R\ Reid -Rv Satnam; R v Kevra/ - Coincidence of acft« re«i and /nens rea - Thabo Meli v R - Transferred malice -Rv Pembliton -Rv Latimer 3 Liability without fault 56 Cundy v Le Cocq - Sherras v De Rutzen - SWef v Parsley - L/OT CA/« /4/£ v R - Gammon Ltd v Attomey-General for Hong Kong - Pharmaceutical Society ofGreat Britain v Storkwain 4 Factors affecting fault 74 Mistake - Mistake of fact negativing fault -Rv Tolson - DPP v Morgan - Mistake as to an excuse or justification - R v Kimber - R v Williams (Gladstone) - Beckford v R - Intoxication - DPP v Majewski - Rv Caldwell - Rv Hardie - R v Woods - R v O'Grady - Mental Disorder - M'Naghten's Case -Rv Kemp - Rv Sullivan - R v Hennessy -

Criminal Law

The Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 96) CRIMINAL LAW OFFENCES RELATING TO INTERFERENCE WITH THE COURSE OF JUSTICE Laid before Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to heprinted 7th November 1979 LONDON HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE 213 24.50 net k The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Commissioners are- The Honourable Mr. Justice Kerr, Chairman. Mr. Stephen M. Cretney. Mr. Stephen Edell. Mr. W. A. B. Forbes, Q.C. Dr. Peter M. North. The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr. J. C. R. Fieldsend and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London, WClN 2BQ. 11 THE LAW COMMISSION CRIMINAL LAW CONTENTS Paragraph Page PART I: INTRODUCTION .......... 1.1-1.9 1 PART 11: PERJURY A . PRESENT LAW AND WORKING PAPER PROPOSALS ............. 2.1-2.7 4 1. Thelaw .............. 2.1-2.3 4 2 . The incidence of offences under the Perjury Act 1911 .............. 2.4-2.5 5 3. Working paper proposals ........ 2.6-2.7 7 B . RECOMMENDATIONS AS TO PERJURY IN JUDICIAL PROCEEDINGS ........ 2.8-2.93 8 1. The problem of false evidence not given on oath and the meaning of “judicial proceedings” ............ 2.8-2.43 8 (a) Working paperproposals ...... 2.9-2.10 8 (b) The present law .......... 2.1 1-2.25 10 (i) The Evidence Act 1851. section 16 2.12-2.16 10 (ii) Express statutory powers of tribunals ......... -

The Abolition of the Death Penalty in the United Kingdom

The Abolition of the Death Penalty in the United Kingdom How it Happened and Why it Still Matters Julian B. Knowles QC Acknowledgements This monograph was made possible by grants awarded to The Death Penalty Project from the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, the United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the Sigrid Rausing Trust, the Oak Foundation, the Open Society Foundation, Simons Muirhead & Burton and the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture. Dedication The author would like to dedicate this monograph to Scott W. Braden, in respectful recognition of his life’s work on behalf of the condemned in the United States. © 2015 Julian B. Knowles QC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. Copies of this monograph may be obtained from: The Death Penalty Project 8/9 Frith Street Soho London W1D 3JB or via our website: www.deathpenaltyproject.org ISBN: 978-0-9576785-6-9 Cover image: Anti-death penalty demonstrators in the UK in 1959. MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARY 2 Contents Foreword .....................................................................................................................................................4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................5 A brief