Tom Crean Antarctic Explorer Born to Explore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Landscapes of Exploration' Education Pack

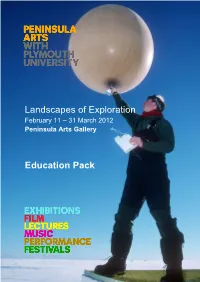

Landscapes of Exploration February 11 – 31 March 2012 Peninsula Arts Gallery Education Pack Cover image courtesy of British Antarctic Survey Cover image: Launch of a radiosonde meteorological balloon by a scientist/meteorologist at Halley Research Station. Atmospheric scientists at Rothera and Halley Research Stations collect data about the atmosphere above Antarctica this is done by launching radiosonde meteorological balloons which have small sensors and a transmitter attached to them. The balloons are filled with helium and so rise high into the Antarctic atmosphere sampling the air and transmitting the data back to the station far below. A radiosonde meteorological balloon holds an impressive 2,000 litres of helium, giving it enough lift to climb for up to two hours. Helium is lighter than air and so causes the balloon to rise rapidly through the atmosphere, while the instruments beneath it sample all the required data and transmit the information back to the surface. - Permissions for information on radiosonde meteorological balloons kindly provided by British Antarctic Survey. For a full activity sheet on how scientists collect data from the air in Antarctica please visit the Discovering Antarctica website www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk and select resources www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk has been developed jointly by the Royal Geographical Society, with IBG0 and the British Antarctic Survey, with funding from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) supports geography in universities and schools, through expeditions and fieldwork and with the public and policy makers. Full details about the Society’s work, and how you can become a member, is available on www.rgs.org All activities in this handbook that are from www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk will be clearly identified. -

Endurance: a Glorious Failure – the Imperial Transantarctic Expedition 1914 – 16 by Alasdair Mcgregor

Endurance: A glorious failure – The Imperial Transantarctic Expedition 1914 – 16 By Alasdair McGregor ‘Better a live donkey than a dead lion’ was how Ernest Shackleton justified to his wife Emily the decision to turn back unrewarded from his attempt to reach the South Pole in January 1909. Shackleton and three starving, exhausted companions fell short of the greatest geographical prize of the era by just a hundred and sixty agonising kilometres, yet in defeat came a triumph of sorts. Shackleton’s embrace of failure in exchange for a chance at survival has rightly been viewed as one of the greatest, and wisest, leadership decisions in the history of exploration. Returning to England and a knighthood and fame, Shackleton was widely lauded for his achievement in almost reaching the pole, though to him such adulation only heightened his frustration. In late 1910 news broke that the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen would now vie with Shackleton’s archrival Robert Falcon Scott in the race to be first at the pole. But rather than risk wearing the ill-fitting and forever constricting suit of the also-ran, Sir Ernest Shackleton then upped the ante, and in March 1911 announced in the London press that the crossing of the entire Antarctic continent via the South Pole would thereafter be the ultimate exploratory prize. The following December Amundsen triumphed, and just three months later, Robert Falcon Scott perished; his own glorious failure neatly tailored for an empire on the brink of war and searching for a propaganda hero. The field was now open for Shackleton to hatch a plan, and in December 1913 the grandiloquently titled Imperial Transantarctic Expedition was announced to the world. -

Tom Crean – Antarctic Explorer

Tom Crean – Antarctic Explorer Mount Robert Falcon Scott compass The South Pole Inn Terra Nova Fram Amundsen camp Royal Navy Weddell Endurance coast-to-coast Annascaul food Elephant Georgia glacier Ringarooma experiments scurvy south wrong Tom Crean was born in __________, Co. Kerry in 1877. When he was 15 he joined the_____ _____. While serving aboard the __________ in New Zealand, he volunteered for the Discovery expedition to the Antarctic. The expedition was led by Captain __________ _________ __________. The aim of the expedition was to explore any lands that could be reaching and to conduct scientific __________. Tom Crean was part of the support crew and was promoted to Petty Officer, First Class for all his hard work. Captain Scott did not reach the South Pole on this occasion but he did achieve a new record of furthest __________. Tom Crean was asked to go on Captain Scott’s second expedition called __________ __________to Antarctica. This time Captain Scott wanted to be the first to reach the South Pole. There was also a Norwegian expedition called __________ led by Roald __________ who wanted to be the first to reach the South Pole. Tom Crean was chosen as part of an eight man team to go to the South Pole. With 250km to go to the South Pole, Captain Scott narrowed his team down to five men and ordered Tom Crean, Lieutenant Evans and Lashly to return to base _______. Captain Scott made it to the South Pole but were beaten to it by Amundsen. They died on the return journey to base camp. -

Navigation on Shackleton's Voyage to Antarctica

Records of the Canterbury Museum, 2019 Vol. 33: 5–22 © Canterbury Museum 2019 5 Navigation on Shackleton’s voyage to Antarctica Lars Bergman1 and Robin G Stuart2 1Saltsjöbaden, Sweden 2Valhalla, New York, USA Email: [email protected] On 19 January 1915, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, under the leadership of Sir Ernest Shackleton, became trapped in their vessel Endurance in the ice pack of the Weddell Sea. The subsequent ordeal and efforts that lead to the successful rescue of all expedition members are the stuff of legend and have been extensively discussed elsewhere. Prior to that time, however, the voyage had proceeded relatively uneventfully and was dutifully recorded in Captain Frank Worsley’s log and work book. This provides a window into the navigational methods used in the day-to- day running of the ship by a master mariner under normal circumstances in the early twentieth century. The conclusions that can be gleaned from a careful inspection of the log book over this period are described here. Keywords: celestial navigation, dead reckoning, double altitudes, Ernest Shackleton, Frank Worsley, Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, Mercator sailing, time sight Introduction On 8 August 1914, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic passage in the 22½ foot (6.9 m) James Caird to Expedition under the leadership of Sir Ernest seek rescue from South Georgia. It is ultimately Shackleton set sail aboard their vessel the steam a tribute to Shackleton’s leadership and Worsley’s yacht (S.Y.) Endurance from Plymouth, England, navigational skills that all survived their ordeal. with the goal of traversing the Antarctic Captain Frank Worsley’s original log books continent from the Weddell to Ross Seas. -

Tom Crean Resources

Tom Crean – Antarctic Explorer Mount Robert Falcon Scott compass The South Pole Inn Terra Nova Fram Amundsen camp Royal Navy Weddell Endurance coast-to-coast Annascaul food Elephant Georgia glacier Ringarooma experiments scurvy south wrong Tom Crean was born in __________, Co. Kerry in 1877. When he was 16 he joined the_____ _____. While serving aboard the __________ in New Zealand, he volunteered for the Discovery expedition to the Antarctic. The expedition was led by Captain __________ _________ __________. The aim of the expedition was to explore any lands that could be reaching and to conduct scientific __________. Tom Crean was part of the support crew and was promoted to Petty Officer, First Class for all his hard work. Captain Scott did not reach the South Pole on this occasion but he did achieve a new record of furthest __________. Tom Crean was asked to go on Captain Scott’s second expedition called __________ __________to Antarctica. This time Captain Scott wanted to be the first to reach the South Pole. There was also a Norwegian expedition called __________ led by Roald __________ who wanted to be the first to reach the South Pole. Tom Crean was chosen as part of an eight man team to go to the South Pole. With 250km to go to the South Pole, Captain Scott narrowed his team down to five men and ordered Tom Crean, Lieutenant Evans and Lashly to return to base _______. Captain Scott made it to the South Pole but were beaten to it by Amundsen. They died on the return journey to base camp. -

One of the Most Famous and Courageous New Zealanders That Many of Us Have Never Heard Of!

One of the most famous and courageous New Zealanders that many of us have never heard of! This book is a biography of Frank Worsley, without doubt one of New Zealand’s greatest, but largely unsung adventuring heroes. Born in Akaroa he went to sea as a teenager in 1888 on the sailing ships plying their trade between New Zealand and England. But the greatest adventure of his life began when he became the captain of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s ship Endurance, which was trapped in pack ice on the 1914–1916 Antarctic expedition and slowly crushed. The crew of 28 spent over a year camped on the Antarctic ice before Shackleton, Worsley and four others sailed a tiny lifeboat across the wild Southern Ocean to South Georgia to summon help for the rest of the men, who were all eventually rescued. This 17-day journey remains one of the greatest ever feats of seamanship and relied totally on Worsley’s brilliant navigation. Worsley was more than just Shackleton’s captain however. For the rest of his life he continued to seek adventures in a manner contemporaries described as ‘fearless’, being decorated for bravery in both world wars, and continuing to captain ships all around the world. This is a revision of John Thomson’s 1998 book Shackleton’s Captain and features new information and illustrations to refresh a story that deserves to be retold for future generations. The story of this proud New Zealander’s remarkable approach to life, far from home, will inspire young men and women who dare to lift their gaze above the ordinary. -

Thesis Template

Thinking with photographs at the margins of Antarctic exploration A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Canterbury by Kerry McCarthy University of Canterbury 2010 Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... 2 List of Figures and Tables ............................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................... 6 Abstract ........................................................................................................................... 7 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Thinking with photographs ....................................................................... 10 1.2 The margins ............................................................................................... 14 1.3 Antarctic exploration ................................................................................. 16 1.4 The researcher ........................................................................................... 20 1.5 Overview ................................................................................................... 22 2 An unauthorised genealogy of thinking with photographs .............................. 27 2.1 The -

We Look for Light Within

“We look for light from within”: Shackleton’s Indomitable Spirit “For scientific discovery, give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel, give me Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when you are seeing no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.” — Raymond Priestley Shackleton—his name defines the “Heroic Age of Antarctica Exploration.” Setting out to be the first to the South Pole and later the first to cross the frozen continent, Ernest Shackleton failed. Sent home early from Robert F. Scott’s Discovery expedition, seven years later turning back less than 100 miles from the South Pole to save his men from certain death, and then in 1914 suffering disaster at the start of the Endurance expedition as his ship was trapped and crushed by ice, he seems an unlikely hero whose deeds would endure to this day. But leadership, courage, wisdom, trust, empathy, and strength define the man. Shackleton’s spirit continues to inspire in the 100th year after the rescue of the Endurance crew from Elephant Island. This exhibit is a learning collaboration between the Rauner Special Collections Library and “Pole to Pole,” an environmental studies course taught by Ross Virginia examining climate change in the polar regions through the lens of history, exploration and science. Fifty-one Dartmouth students shared their research to produce this exhibit exploring Shackleton and the Antarctica of his time. Discovery: Keeping Spirits Afloat In 1901, the first British Antarctic expedition in sixty years commenced aboard the Discovery, a newly-constructed vessel designed specifically for this trip. -

After Editing

Shackleton Dates AUGUST 8th 1914 The team leave the UK on the ship, Endurance. DEC 5th 1914 They arrive at the edge of the Antarctic pack ice, in the Weddell Sea. JAN 18th 1915 Endurance becomes frozen in the pack ice. OCT 27TH 1915 Endurance is crushed in the ice after drifting for 9 months. Ship is abandoned and crew start to live on the pack ice. NOV 1915 Endurance sinks; men start to set up a camp on the ice. DEC 1915 The pack ice drifts slowly north; Patience camp is set up. MARCH 23rd 2016 They see land for the first time – 139 days have passed; the land can’t be reached though. APRIL 9th 2016 The pack ice starts to crack so the crew take to the lifeboats. APRIL 15th 1916 The 3 crews arrive on ELEPHANT ISLAND where they set up camp. APRIL 24th 1916 5 members of the team, including Shackleton, leave in the lifeboat James Caird, on an 800 mile journey to South Georgia, for help. MAY 10TH 1916 The James Caird crew arrive in the south of South Georgia. MAY 19TH -20TH Shackleton, Crean and Worsley walk across South Georgis to the whaling station at Stromness. MAY 23RD 1916 All the men on Elephant Island are safe; Shackleton starts on his first attempt at a rescue from South Georgia but ice prevents him. AUGUST 25th Shackleton leaves on his 4th attempt, on the Chilian tug boat Yelcho; he arrives on Elephant Island on August 30th and rescues all his crew. MAY 1917 All return to England. -

THE PUBLICATION of the NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY Vol 34, No

THE PUBLICATION OF THE NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY Vol 34, No. 3, 2016 34, No. Vol 03 9 770003 532006 Vol 34, No. 3, 2016 Issue 237 Contents www.antarctic.org.nz is published quarterly by the New Zealand Antarctic Society Inc. ISSN 0003-5327 30 The New Zealand Antarctic Society is a Registered Charity CC27118 EDITOR: Lester Chaplow ASSISTANT EDITOR: Janet Bray New Zealand Antarctic Society PO Box 404, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand Email: [email protected] INDEXER: Mike Wing The deadlines for submissions to future issues are 1 November, 1 February, 1 May and 1 August. News 25 Shackleton’s Bad Lads 26 PATRON OF THE NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY: From Gateway City to Volunteer Duty at Scott Base 30 Professor Peter Barrett, 2008 NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY How You Can Help Us Save Sir Ed’s Antarctic Legacy 33 LIFE MEMBERS The Society recognises with life membership, First at Arrival Heights 34 those people who excel in furthering the aims and objectives of the Society or who have given outstanding service in Antarctica. They are Conservation Trophy 2016 36 elected by vote at the Annual General Meeting. The number of life members can be no more Auckland Branch Midwinter Celebration 37 than 15 at any one time. Current Life Members by the year elected: Wellington Branch – 2016 Midwinter Event 37 1. Jim Lowery (Wellington), 1982 2. Robin Ormerod (Wellington), 1996 3. Baden Norris (Canterbury), 2003 Travelling with the Huskies Through 4. Bill Cranfield (Canterbury), 2003 the Transantarctic Mountains 38 5. Randal Heke (Wellington), 2003 6. Bill Hopper (Wellington), 2004 Hillary’s TAE/IGY Hut: Calling all stories 40 7. -

The Centenary of the Scott Expedition to Antarctica and of the United Kingdom’S Enduring Scientific Legacy and Ongoing Presence There”

Debate on 18 October: Scott Expedition to Antarctica and Scientific Legacy This Library Note provides background reading for the debate to be held on Thursday, 18 October: “the centenary of the Scott Expedition to Antarctica and of the United Kingdom’s enduring scientific legacy and ongoing presence there” The Note provides information on Antarctica’s geography and environment; provides a history of its exploration; outlines the international agreements that govern the territory; and summarises international scientific cooperation and the UK’s continuing role and presence. Ian Cruse 15 October 2012 LLN 2012/034 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of the House of Lords and their personal staff, to provide impartial, politically balanced briefing on subjects likely to be of interest to Members of the Lords. Authors are available to discuss the contents of the Notes with the Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Any comments on Library Notes should be sent to the Head of Research Services, House of Lords Library, London SW1A 0PW or emailed to [email protected]. Table of Contents 1.1 Geophysics of Antarctica ....................................................................................... 1 1.2 Environmental Concerns about the Antarctic ......................................................... 2 2.1 Britain’s Early Interest in the Antarctic .................................................................... 4 2.2 Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration ....................................................................... -

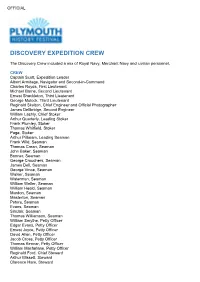

Discovery: Crew List

OFFICIAL DISCOVERY EXPEDITION CREW The Discovery Crew included a mix of Royal Navy, Merchant Navy and civilian personnel. CREW Captain Scott, Expedition Leader Albert Armitage, Navigator and Second-in-Command Charles Royds, First Lieutenant Michael Barne, Second Lieutenant Ernest Shackleton, Third Lieutenant George Mulock, Third Lieutenant Reginald Skelton, Chief Engineer and Official Photographer James Dellbridge, Second Engineer William Lashly, Chief Stoker Arthur Quarterly, Leading Stoker Frank Plumley, Stoker Thomas Whitfield, Stoker Page, Stoker Arthur Pilbeam, Leading Seaman Frank Wild, Seaman Thomas Crean, Seaman John Baker, Seaman Bonner, Seaman George Crouchers, Seaman James Dell, Seaman George Vince, Seaman Walker, Seaman Waterman, Seaman William Weller, Seaman William Heald, Seaman Mardon, Seaman Masterton, Seaman Peters, Seaman Evans, Seaman Sinclair, Seaman Thomas Williamson, Seaman William Smythe, Petty Officer Edgar Evans, Petty Officer Ernest Joyce, Petty Officer David Allan, Petty Officer Jacob Cross, Petty Officer Thomas Kennar, Petty Officer William Macfarlane, Petty Officer Reginald Ford, Chief Steward Arthur Blissett, Steward Clarence Hare, Steward OFFICIAL Dowsett, Steward Gilbert Scott, Steward Roper, Cook Brett, Cook Charles Clarke, 2nd Cook Clarke, Laboratory Assistant Buckridge, Laboratory Assistant Fred Dailey, Carpenter James Duncan, Carpenter’s Mate & Shipwright Thomas Feather, Boatswain (Bosun) Miller, Sailmaker Hubert, Donkeyman SCIENTIFIC Dr George Murray, Chief Scientist (left the ship at Cape Town) Louis Bernacchi, Physicist Hartley Ferrar, Geologist Thomas Vere Hodgson, Marine Biologist Reginald Koettlitz, Doctor Edward Wilson, Junior Doctor and Zoologist .