Arxiv:0805.1250V2 [Astro-Ph] 22 Oct 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of Contributions

Mapping the X-ray Sky with SRG: First Results from eROSITA and ART-XC Report of Contributions https://events.mpe.mpg.de/e/SRG2020 Mapping the X- … / Report of Contributions eROSITA discovery of a new AGN … Contribution ID : 4 Type : Oral Presentation eROSITA discovery of a new AGN state in 1H0707-495 Tuesday, 17 March 2020 17:45 (15) One of the most prominent AGNs, the ultrasoft Narrow-Line Seyfert 1 Galaxy 1H0707-495, has been observed with eROSITA as one of the first CAL/PV observations on October 13, 2019 for about 60.000 seconds. 1H 0707-495 is a highly variable AGN, with a complex, steep X-ray spectrum, which has been the subject of intense study with XMM-Newton in the past. 1H0707-495 entered an historical low hard flux state, first detected with eROSITA, never seen before in the 20 years of XMM-Newton observations. In addition ultra-soft emission with a variability factor of about 100 has been detected for the first time in the eROSITA light curves. We discuss fast spectral transitions between the cool and a hot phase of the accretion flow in the very strong GR regime as a physical model for 1H0707-495, and provide tests on previously discussed models. Presenter status Senior eROSITA consortium member Primary author(s) : Prof. BOLLER, Thomas (MPE); Prof. NANDRA, Kirpal (MPE Garching); Dr LIU, Teng (MPE Garching); MERLONI, Andrea; Dr DAUSER, Thomas (FAU Nürnberg); Dr RAU, Arne (MPE Garching); Dr BUCHNER, Johannes (MPE); Dr FREYBERG, Michael (MPE) Presenter(s) : Prof. BOLLER, Thomas (MPE) Session Classification : AGN physics, variability, clustering October 3, 2021 Page 1 Mapping the X- … / Report of Contributions X-ray emission from warm-hot int … Contribution ID : 9 Type : Poster X-ray emission from warm-hot intergalactic medium: the role of resonantly scattered cosmic X-ray background We revisit calculations of the X-ray emission from warm-hot intergalactic medium (WHIM) with particular focus on contribution from the resonantly scattered cosmic X-ray background (CXB). -

ASTRONOMY and ASTROPHYSICS the Elliptical Galaxy Formerly Known As the Local Group: Merging the Globular Cluster Systems

Astron. Astrophys. 358, 471–480 (2000) ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS The elliptical galaxy formerly known as the Local Group: merging the globular cluster systems Duncan A. Forbes1,2, Karen L. Masters1, Dante Minniti3, and Pauline Barmby4 1 University of Birmingham, School of Physics and Astronomy, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK 2 Swinburne University of Technology, Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Hawthorn, Victoria 3122, Australia 3 P. Universidad Catolica,´ Departamento de Astronom´ıa y Astrof´ısica, Casilla 104, Santiago 22, Chile 4 Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA Received 5 November 1999 / Accepted 27 January 2000 Abstract. Prompted by a new catalogue of M31 globular clus- al. 1995; Minniti et al. 1996). Furthermore Hubble Space Tele- ters, we have collected together individual metallicity values for scope studies of merging disk galaxies reveal evidence for the globular clusters in the Local Group. Although we briefly de- GC systems of the progenitor galaxies (e.g. Forbes & Hau 1999; scribe the globular cluster systems of the individual Local Group Whitmore et al. 1999). Thus GCs should survive the merger of galaxies, the main thrust of our paper is to examine the collec- their parent galaxies, and will form a new GC system around tive properties. In this way we are simulating the dissipationless the newly formed elliptical galaxy. merger of the Local Group, into presumably an elliptical galaxy. The globular clusters of the Local Group are the best studied Such a merger is dominated by the Milky Way and M31, which and offer a unique opportunity to examine their collective prop- appear to be fairly typical examples of globular cluster systems erties (reviews of LG star clusters can be found in Brodie 1993 of spiral galaxies. -

Maffei 1970 the MEMBER Technology, (H

THE ASTROPHYSICAL JOURNAL, 163:L25-L31, 1971January1 @ 1971. The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. 1971ApJ...163L..25S MAFFEI 1: A NEW MASSIVE MEMBER OF THE LOCAL GROUP? HYRON SPINRAD,* w. L. w. SARGENT,t J.B. 0KE,t GERRY NEUGEBAUER,t ROBERT LANDAU,* IVAN R. KING,* }AMES E. GUNN,t GORDON GARMIRE,t AND NANNIELOU H. DIETER§ Received 1970 November 2 ABSTRACT An extensive collection of observational data is presented which indicates that the recently dis covered infrared object Maffei 1 is a highly reddened giant elliptical galaxy at a distance of about 1 Mpc, and thus is probably a new massive member of the Local Group. I. INTRODUCTION In 1968, Maffei (1968) discovered two infrared objects in the neighborhood of IC 1805. The objects are conspicuous as extended, elliptical sources on I-N plates, but are just barely visible on the blue 48-inch Palomar Sky Survey plates. They are located in the plane of the Galaxy at approximately zn = 136°, bII = -0.5°; the two objects are separated by about 40'. At 2.2 µ, where differences due to interstellar extinction are small, the flux from the central 8" of Maffei 1 is comparable to that from a similar area of M31. Nonthermal radio emission at 3, 4, and 9 cm has been detected from Maffei 2 by Bell, Seaquist, and Brown (1970), although no radio emisssion was observed from Maffei 1. The possibility that these objects are reddened external galaxies, and possibly even members of the Local Group of galaxies, has led to an observational program among observers at the Leuschner, Lick, and Hale Observatories which utilizes a variety of techniques covering wavelengths from 0.4 to 3.5 µ. -

Astronomy 2009 Index

Astronomy Magazine 2009 Index Subject Index 1RXS J160929.1-210524 (star), 1:24 4C 60.07 (galaxy pair), 2:24 6dFGS (Six Degree Field Galaxy Survey), 8:18 21-centimeter (neutral hydrogen) tomography, 12:10 93 Minerva (asteroid), 12:18 2008 TC3 (asteroid), 1:24 2009 FH (asteroid), 7:19 A Abell 21 (Medusa Nebula), 3:70 Abell 1656 (Coma galaxy cluster), 3:8–9, 6:16 Allen Telescope Array (ATA) radio telescope, 12:10 ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/sub-millimeter Array), 4:21, 9:19 Alpha (α) Canis Majoris (Sirius) (star), 2:68, 10:77 Alpha (α) Orionis (star). See Betelgeuse (Alpha [α] Orionis) (star) Alpha Centauri (star), 2:78 amateur astronomy, 10:18, 11:48–53, 12:19, 56 Andromeda Galaxy (M31) merging with Milky Way, 3:51 midpoint between Milky Way Galaxy and, 1:62–63 ultraviolet images of, 12:22 Antarctic Neumayer Station III, 6:19 Anthe (moon of Saturn), 1:21 Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST), 4:24 APEX (Atacama Pathfinder Experiment) radio telescope, 3:19 Apollo missions, 8:19 AR11005 (sunspot group), 11:79 Arches Cluster, 10:22 Ares launch system, 1:37, 3:19, 9:19 Ariane 5 rocket, 4:21 Arianespace SA, 4:21 Armstrong, Neil A., 2:20 Arp 147 (galaxy pair), 2:20 Arp 194 (galaxy group), 8:21 art, cosmology-inspired, 5:10 ASPERA (Astroparticle European Research Area), 1:26 asteroids. See also names of specific asteroids binary, 1:32–33 close approach to Earth, 6:22, 7:19 collision with Jupiter, 11:20 collisions with Earth, 1:24 composition of, 10:55 discovery of, 5:21 effect of environment on surface of, 8:22 measuring distant, 6:23 moons orbiting, -

The Detection of Bright Asymptotic Giant Branch Stars in the Nearby Elliptical Galaxy Maffei 1

THE DETECTION OF BRIGHT ASYMPTOTIC GIANT BRANCH STARS IN THE NEARBY ELLIPTICAL GALAXY MAFFEI 1 T. J. Davidge 1 Canadian Gemini Office, Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, National Research Council of Canada, 5071 W. Saanich Road, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada V9E 2E7 email: [email protected] Sidney van den Bergh Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, National Research Council of Canada, 5071 W. Saanich Road, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada V9E 2E7 email: [email protected] ABSTRACT We have used the adaptive optics system on the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope to study a field 6 arcmin from the center of the heavily obscured elliptical galaxy Maffei 1. Our near diffraction-limited H and K0 images reveal an excess population of objects with respect to a background field, and we conclude that the asymptotic giant branch tip (AGB-tip) in Maffei 1 occurs at K =20 0:25. Assuming that stars at the AGB-tip in Maffei 1 have the ± same intrinsic luminosity as those in the bulge of M31, then the actual distance modulus of Maffei 1 is 28:2 0:3ifAV =5:1, which corresponds to a distance +0:6 ± of 4:4 0:5 Mpc. This is in excellent agreement with the distance estimated from − surface brightness flucuations in the infrared, and confirms that Maffei 1 is too distant to significantly affect the dynamics of the Local Group. Subject headings: galaxies: individual (Maffei 1) – galaxies: distances and redshifts 1Visiting Astronomer, Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope, which is operated by the National Research Council of Canada, the Centre National de le Recherche Scientifique, and the University of Hawaii. -

Bright Nebula Observing Program

Contact information: Inside this issue: Info Officer (General Info) – [email protected] Website Administrator – [email protected] Page January Club Calendar 3 Postal Address: Fort Worth Astronomical Society Tandy Hills Star Party Info 4 c/o Matt McCullar Cloudy Nights Review 5.,6 5801 Trail Lake Drive Fort Worth, TX 76133 Celestial Events 7 Web Site: http://www.fortworthastro.org (or .com) Object of the Month 8 Facebook: http://tinyurl.com/3eutb22 Twitter: http://twitter.com/ftwastro AL Observing Program 9,10,11,12 Yahoo! eGroup (members only): http://tinyurl.com/7qu5vkn ISS visibility info 13 Officers (2018-2020): Planetary Visibility info 13 President – Chris Mlodnicki , [email protected] Vice President – Fred Klich , [email protected] Sky Chart for Month 14 Tres – Laura Cowles, [email protected] Lunar Calendar 15 Secretary—Pam Klich, [email protected] Lunar Info 16 Board Members: Mars/Saturn Data 17 2018-2020 Phil Stage Fundraising/Donation Info 18,19 Robin Pond Photo Files 20 John McCrea Pam Kloepfer Cover Photo: IC1848 Photo via Alberto Pisabarro Observing Site Reminders: Be careful with fire, mind all local burn bans! Dark Site Usage Requirements (ALL MEMBERS): • Maintain Dark-Sky Etiquette (http://tinyurl.com/75hjajy) • Turn out your headlights at the gate! Ed itor : • Sign the logbook (in camo-painted storage shed. Inside the door on the left- hand side) George C. Lutch • Log club equipment problems (please contact a FWAS board member to inform them of any problems) • Put equipment back neatly when finished Issue Contribu- • Last person out: to rs : Check all doors – secured, but NOT locked Make sure nothing is left out Pa m K l ic h The Fort Worth Astronomical Society (FWAS) was founded in 1949 and is a non-profit 501(c)3 Matt McCullar scientific educational organization, and incorporated in the state of Texas. -

1 Introduction

Astr 555 Class Notes { Fall 2016 1 1 Introduction • What are galaxies? What are they composed of? { Galaxies: gravitationally bound collections of stars, gas/dust, dark matter, black holes • Galaxies as crossroads of astronomy: stellar physics, gas physics, cosmology • Understanding galaxy formation one of the current largest problems in astron- omy; almost all fields can be regarded as important for understanding galaxy formation! • Galaxies are luminous tracers of large scale structure, act as cosmological probes Goals of course: • Understand general current picture of galaxies and galaxy evolution • Basic understanding of how galaxies are observed • Review statistical properties of the galaxy population, and specific properties of different types of galaxies • Understand physical tools by which we learn and characterize different compo- nents of galaxies • If time permits: what we can learn from the Milky Way Note content cannot be complete, and that ideas/data change with time! Note place of ASTR555 in curriculum: ASTR555 to provide basic overview of galaxies and their components, ASTR616 to focus on galaxy formation and evolution. Class organization and assignments: • web page accessible through Canvas • basic order of presentation : observing galaxies, galaxy properties and charac- teristics, galaxies toolkit: stars, gas, dust, central black holes/galactic nucleii, dark matter/masses • web material/notes • books/other resources • responsibilities of students { Students will think about/review material covered in each class, and ask questions either during presentation or at the beginning of the following class { Formal assignments Astr 555 Class Notes { Fall 2016 2 ∗ reading / questions ∗ problems / projects ∗ exams Note that the main content of the course is a survey of material. -

Reflectionsreflections the Newsletter of the Popular Astronomy Club ESTABLISHED 1936 February 2021

Affiliated with ReflectionsReflections The Newsletter of the Popular Astronomy Club ESTABLISHED 1936 February 2021 President’s Corner February 2021 the speed of light, this means the object is Welcome to the Febru- trapped in the black hole. ary edition of Reflec- The escape velocity for a planet is the speed at tions. We are in the which an object (like a rocket) would have to middle of winter, which be launched from the surface of the planet so should be obvious to that it would fly up and completely escape Page Topic everyone and especially from the planet and never fall back down for astronomers. We again. A rocket could orbit a planet at a slightly 1-2 Presidents have had very few op- slower speed and never fall back to the Corner Alan Sheidler portunities to view ce- planet’s surface, but in that case, the rocket 2-4 Announcements lestial objects and when would not have escaped, it would have been 5-10 Contributions we have, it has been too cold or snowy for trapped in an orbit around the planet. 11 Astronomy in most of us to get out under the stars. Print We can calculate the escape velocity for the For many of us, this is a time when we take a 12-13 Skyward Earth and other solar system objects using the vacation from observing and do other things 14 Upcoming Events fairly simple equation below. For those of you (like buy new telescopes or plan observing 15 Sign-Up Sheet not wanting to bother doing the math, I creat- sessions when the weather improves this 16 Astronomical ed the following table showing the escape ve- spring). -

The Distance and Motion of the Maffei Group

Draft version February 27, 2019 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX62 The Distance and Motion of the Maffei Group Gagandeep S. Anand,1 R. Brent Tully,1 Luca Rizzi,2 and Igor D. Karachentsev3 1Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA 2W. M. Keck Observatory, 65-1120 Mamalahoa Hwy., Kamuela, HI 96743, USA 3Special Astrophysical Observatory, Nizhniy Arkhyz, Karachai-Cherkessia 369167, Russia ABSTRACT It has recently been suggested that the nearby galaxies Maffei 1 and 2 are further in distance than previously thought, such that they no longer are members of the same galaxy group as IC 342. We reanalyze near-infrared photometry from the Hubble Space Telescope, and find a distance to Maffei 2 of 5:73 ± 0:40 Mpc. With this distance, the Maffei Group lies 2.5 Mpc behind the IC 342 Group and has a peculiar velocity toward the Local Group of −128 ± 33 km s−1. The negative peculiar velocities of both of these distinct galaxy groups are likely the manifestation of void expansion from the direction of Perseus-Pisces. 1. INTRODUCTION in the optical (Rizzi et al. 2007), and somewhat larger in Our collaboration (Wu et al. 2014) determined an av- the near-infrared (Dalcanton et al. 2012; Wu et al. 2014). eraged distance to the galaxies Maffei 1 & 2 of 3.4 ± 0.2 TRGB distances to unobscured galaxies within 10 Mpc Mpc from Tip of the Red Giant Branch (TRGB) mea- can be achieved with a single orbit with HST (Rizzi et surements based on near infrared photometry of Hubble al. -

Extragalactic Database. VII Reduction of Astrophysical Parameters

A&A manuscript no. (will be inserted by hand later) ASTRONOMY AND Your thesaurus codes are: ASTROPHYSICS 11.19.2; 11.16.1; 11.09.4; 11.06.2; 04.01.1 26.3.2021 Extragalactic Database: VII Reduction of astrophysical parameters G. Paturel1, H. Andernach1, L. Bottinelli2+3, H. Di Nella1, N. Durand2, R. Garnier1, L. Gouguenheim2+3, P. Lanoix1 M.C. Marthinet1, C. Petit1, J. Rousseau1, G. Theureau2, and I. Vauglin1 1 CRAL-Observatoire de Lyon, UMR 5574 F69230 Saint-Genis Laval, FRANCE, 2 Observatoire de Paris-Meudon, URA 1757 F92195 Meudon Principal Cedex 3 Universit´eParis-Sud F91405 Orsay, FRANCE Received September 10; accepted November 05, 1996 Abstract. The Lyon-Meudon Extragalactic database (LEDA) gives a free access to the main astrophysical pa- rameters for more than 100,000 galaxies. The most com- 1. Introduction mon names are compiled allowing users to recover quickly any galaxy. All these measured astrophysical parame- This paper gives a detailed description of the reduc- ters are first reduced to a common system according to tion of astrophysical parameters available through LEDA well defined reduction formulae leading to mean homo- database for more than 100,000 galaxies. It is often re- geneized parameters. Further, these parameters are also quired by users of LEDA who need a reference where the transformed into corrected parameters from widely ac- description of parameters reduction is given. Most of these cepted models. For instance, raw 21-cm line widths are reduction procedures were described in previous studies: transformed into mean standard widths after correction – Central velocity dispersion (Davoust et al., 1985) for instrumental effect and then into maximum velocity ro- – Kinematical distance modulus (Bottinelli et al., 1986) tation properly corrected for inclination and non-circular – HI data (HI velocity, flux and 21-cm line width) (Bot- velocity. -

The Upper Asymptotic Giant Branch of the Elliptical Galaxy Maffei 1, and Comparisons with M32 and NGC 5128

THE UPPER ASYMPTOTIC GIANT BRANCH OF THE ELLIPTICAL GALAXY MAFFEI 1, AND COMPARISONS WITH M32 AND NGC 5128 T. J. Davidge 1, 2 Canadian Gemini Office, Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, National Research Council of Canada, 5071 W. Saanich Road, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada V9E 2E7 email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Deep near-infrared images obtained with adaptive optics (AO) systems on the Gemini North and Canada-France-Hawaii telescopes are used to investigate the bright stellar content and central regions of the nearby elliptical galaxy Maffei 1. Stars evolving on the upper asymptotic giant branch (AGB) are resolved in a field 3 arcmin from the center of the galaxy. The locus of bright giants on the (K,H − K) color-magnitude diagram is consistent with a population of stars like those in Baade’s Window reddened by E(H − K)=0.28 ± 0.05 mag. This corresponds to AV =4.5 ± 0.8 mag, and is consistent with previous estimates of the line of sight extinction computed from the integrated properties of Maffei 1. The AGB-tip occurs at K = 20.0, which correponds to MK = −8.7; hence, the AGB-tip brightness in Maffei 1 is comparable to that in M32, NGC 5128, and the bulges of M31 and the Milky-Way. The near-infrared luminosity arXiv:astro-ph/0207122v1 4 Jul 2002 functions (LFs) of bright AGB stars in Maffei 1, M32, and NGC 5128 are also in excellent agreement, both in terms of overall shape and the relative density of infrared-bright stars with respect to the fainter stars that dominate the light at visible and red wavelengths. -

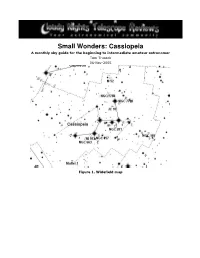

Cassiopeia a Monthly Sky Guide for the Beginning to Intermediate Amateur Astronomer Tom Trusock 06-Nov-2005

Small Wonders: Cassiopeia A monthly sky guide for the beginning to intermediate amateur astronomer Tom Trusock 06-Nov-2005 Figure 1. W idefield map 2/15 Small Wonders: Cassiopeia Target List Object Type Size Mag RA Dec h m s α (alpha) Cassiopeiae (Schedar) Star 2.2 00 40 51.2 +56° 34' 23" h m s η (eta) Cassiopeiae (Achird) Star 3.5 00 49 26.6 +57° 51' 07" M 52 Open Cluster 16.0' 6.9 23h 25m 06.5s +61° 38' 33" NGC 7788 Open Cluster 4.0' 9.4 23h 57m 00.3s +61° 26' 11" NGC 7789 Open Cluster 25.0' 6.7 23h 57m 42.3s +56° 44' 41" NGC 7790 Open Cluster 5.0' 8.5 23h 58m 42.6s +61° 14' 41" NGC 147 Galaxy 13.2'x7.8' 9.4 00h 33m 31.5s +48° 32' 34" NGC 185 Galaxy 8.0'x7.0' 9.3 00h 39m 17.7s +48° 22' 22" NGC 281 Bright Nebula 35.0'x30.0' 00h 53m 20.8s +56° 39' 26" NGC 457 Open Cluster 20.0' 6.4 01h 19m 55.9s +58° 19' 29" M 103 Open Cluster 6.0' 7.4 01h 33m 46.3s +60° 41' 28" NGC 654 Open Cluster 6.0' 6.5 01h 44m 25.0s +61° 54' 54" NGC 659 Open Cluster 6.0' 7.9 01h 44m 48.2s +60° 42' 05" NGC 663 Open Cluster 15.0' 7.1 01h 46m 41.6s +61° 14' 56" Challenge Objects Object Type Size Mag RA Dec IC 10 Galaxy 6.4'x5.3' 11.2 00h 20m 44.3s +59° 19' 43" Maffei 1 Galaxy 5.0'x3.0' 11.4 02h 36m 45.8s +59° 40' 40" Cassiopeia t‘s time to pay homage to the Queen.