PHONOLOGICAL ANALYSIS the Foot Domain in Bambara Christopher R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Meter

Introduction to Meter A stress or accent is the greater amount of force given to one syllable than another. English is a language in which all syllables are stressed or unstressed, and traditional poetry in English has used stress patterns as a fundamental structuring device. Meter is simply the rhythmic pattern of stresses in verse. To scan a poem means to read it for meter, an operation whose noun form is scansion. This can be tricky, for although we register and reproduce stresses in our everyday language, we are usually not aware of what we’re going. Learning to scan means making a more or less unconscious operation conscious. There are four types of meter in English: iambic, trochaic, anapestic, and dactylic. Each is named for a basic foot (usually two or three syllables with one strong stress). Iambs are feet with an unstressed syllable, followed by a stressed syllable. Only in nursery rhymes to do we tend to find totally regular meter, which has a singsong effect, Chidiock Tichborne’s poem being a notable exception. Here is a single line from Emily Dickinson that is totally regular iambic: _ / │ _ / │ _ / │ _ / My life had stood – a loaded Gun – This line serves to notify readers that the basic form of the poem will be iambic tetrameter, or four feet of iambs. The lines that follow are not so regular. Trochees are feet with a stressed syllable, followed by an unstressed syllable. Trochaic meter is associated with chants and magic spells in English: / _ │ / _ │ / _ │ / _ Double, double, toil and trouble, / _ │ / _ │ / _ │ / _ Fire burn and cauldron bubble. -

A Crash Course in Foot Structure

Representations Foot Parsing A Crash Course in Foot Structure Jochen Trommer [email protected] University of Leipzig Department of Linguistics Concatenative Approaches to Nonconcatenative Morphology EGG 2008 Jochen Trommer [email protected] A Crash Course in Foot Structure Representations Foot Parsing Not all syllables are created equal ba A ma la py tech ro nic Jochen Trommer [email protected] A Crash Course in Foot Structure Representations Foot Parsing Word Stress Metrical prominence of syllables in (phonological) words Jochen Trommer [email protected] A Crash Course in Foot Structure Representations Foot Parsing Phonetic Correlates of Word Stress I Length I Loudness I Pitch contour Jochen Trommer [email protected] A Crash Course in Foot Structure Representations Foot Parsing Consequences of Word Stress for Vowel Reduction EI t@m tO mIk @ I Vowels are maintained under stress I and reduced to [@] if unstressed Jochen Trommer [email protected] A Crash Course in Foot Structure Representations Foot Parsing Word Stress in the IPA [man.da."öi:.n@] ["Py:.b5.mO5.g@n] Jochen Trommer [email protected] A Crash Course in Foot Structure Representations Foot Parsing Overview Foot Parsing Jochen Trommer [email protected] A Crash Course in Foot Structure Representations Foot Parsing Prosodic Phonology Iambs&Trochees Hayes (1995) Word Stress in Prosodic Phonology (Selkirk, 1980) Phonological Word Footw Foots σs σw σs σw a la ba ma s = strong w = weak Jochen Trommer [email protected] A Crash Course -

ED 105 498 CS 202 027 Introduction to Poetry. Language Arts

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 105 498 CS 202 027 TITLE Introduction to Poetry. Language Arts Mini-Course. INSTITUTION Lampeter-Strasburg School District, Pa. PUB DATE 73 NOTE 13p.; See related documents CS202024-35; Product of Lampeter-Strasburg High School EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$1.58 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; *Course Descriptions; Course Objectives; *Curriculum Guides; Instructional Materials; *Language Arts; Literature; *Poetry; Secondary Education; *Short Courses IDENTIFIERS Minicourses ABSTRACT This language arts minicourse guide for Lampeter-Strasburg (Pennsylvania) High School contains a topical outline of an introduction to a poetry course. The guide includes a list of twenty course objectives; an outline of the definitions, the stanza forms, and the figures of speech used in poetry; a description of the course content .nd concepts to be studied; a presentation of activities and procedures for the classroom; and suggestions for instructional materials, including movies, records, audiovisual aids, filmstrips, transparencies, and pamphlets and books. (RB) U S Oh PAR TmENT OF HEALTH C EOUCATKIN WELFARE NAT.ONA, INSTITUTE OF EOUCATION Ch DO. Ls. 1 N THA) BE E 4 REPRO ^,,)I qAt L'e AS RECEIVED FROM 1' HI PE 4 sON OR ulICHLNIZA T ION ORIGIN :.' 4L, , T PO,N' s OF .IIE K OR OP .NICINS LiN .." E D DO NOT riFcE SSARL + RE PRE ,E % , Lr lat_ 4.% 00NAL INS T TUT e OF CD c D , .'`N POs. T 1C14 OR POLICY uJ Language Arts Mini-Course INTRODUCTION TO POETRY Lampeter-Strasburg High School ERM.SSION TO RE POODuCETHIS COPY M. 'ED MATERIAL HA; BEEN GRANTED BY Lampeter, Pennsylvania Lampeter-Strasburg High School TD ERIC AV) ORGANIZATIONS OPERATING P.t,EP AGREEMENTS .SiTH THE NATIONAL IN STTuTE Or EDUCATION FURTHER 1973 REPRO PUCTION OU'SIDE THE EPIC SYSTEMRE QUIRES PERMISS'ON OF THE COPYRIGHT OWNER N O INTRODUCTION TO POETRY OBJECTIVES: 1. -

How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed. Julie Ellen Kane Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1999 How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed. Julie Ellen Kane Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Kane, Julie Ellen, "How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed." (1999). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6892. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6892 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been rqxroduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directfy firom the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fiice, vdiile others may be from any typ e o f com pater printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^innm g at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Basic Guide to Latin Meter and Scansion

APPENDIX B Basic Guide to Latin Meter and Scansion Latin poetry follows a strict rhythm based on the quantity of the vowel in each syllable. Each line of poetry divides into a number of feet (analogous to the measures in music). The syllables in each foot scan as “long” or “short” according to the parameters of the meter that the poet employs. A vowel scans as “long” if (1) it is long by nature (e.g., the ablative singular ending in the first declen- sion: puellā); (2) it is a diphthong: ae (saepe), au (laudat), ei (deinde), eu (neuter), oe (poena), ui (cui); (3) it is long by position—these vowels are followed by double consonants (cantātae) or a consonantal i (Trōia), x (flexibus), or z. All other vowels scan as “short.” A few other matters often confuse beginners: (1) qu and gu count as single consonants (sīc aquilam; linguā); (2) h does NOT affect the quantity of a vowel Bellus( homō: Martial 1.9.1, the -us in bellus scans as short); (3) if a mute consonant (b, c, d, g, k, q, p, t) is followed by l or r, the preced- ing vowel scans according to the demands of the meter, either long (omnium patrōnus: Catullus 49.7, the -a in patrōnus scans as long to accommodate the hendecasyllabic meter) OR short (prō patriā: Horace, Carmina 3.2.13, the first -a in patriā scans as short to accommodate the Alcaic strophe). 583 40-Irby-Appendix B.indd 583 02/07/15 12:32 AM DESIGN SERVICES OF # 157612 Cust: OUP Au: Irby Pg. -

Refrain, Again: the Return of the Villanelle

Refrain, Again: The Return of the Villanelle Amanda Lowry French Charlottesville, VA B.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 1992, cum laude M.A., Concentration in Women's Studies, University of Virginia, 1995 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Virginia August 2004 ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ABSTRACT Poets and scholars are all wrong about the villanelle. While most reference texts teach that the villanelle's nineteen-line alternating-refrain form was codified in the Renaissance, the scholar Julie Kane has conclusively shown that Jean Passerat's "Villanelle" ("J'ay perdu ma Tourterelle"), written in 1574 and first published in 1606, is the only Renaissance example of this form. My own research has discovered that the nineteenth-century "revival" of the villanelle stems from an 1844 treatise by a little- known French Romantic poet-critic named Wilhelm Ténint. My study traces the villanelle first from its highly mythologized origin in the humanism of Renaissance France to its deployment in French post-Romantic and English Parnassian and Decadent verse, then from its bare survival in the period of high modernism to its minor revival by mid-century modernists, concluding with its prominence in the polyvocal culture wars of Anglophone poetry ever since Elizabeth Bishop’s "One Art" (1976). The villanelle might justly be called the only fixed form of contemporary invention in English; contemporary poets may be attracted to the form because it connotes tradition without bearing the burden of tradition. Poets and scholars have neither wanted nor needed to know that the villanelle is not an archaic, foreign form. -

POETRY NOTES POETRY Is… a Type of Literature That Expresses Ideas and Feelings, Or Tells a Story in a Specific Form (Usually Using Lines and Stanzas) POETIC FORM

POETRY NOTES POETRY is… a type of literature that expresses ideas and feelings, or tells a story in a specific form (usually using lines and stanzas) POETIC FORM FORM - the A word is dead appearance of the When it is said, words on the page Some say. LINE - a group of words together on one I say it just line of the poem Begins to live That day. STANZA - a group of - Emily Dickinson lines arranged together POETIC SOUND EFFECTS RHYTHM The beat created by the sounds of the words in a poem. Rhythm can be created by using, meter, rhymes, alliteration, and refrain. METER A pattern of stressed (strong) and unstressed (weak) syllables Each unit or part of the pattern is called a “foot” Types of Feet: • Iambic - unstressed, stressed • Trochaic - stressed, unstressed • Anapestic - unstressed, unstressed, stressed • Dactylic - stressed, unstressed, unstressed RHYMES Words sound alike because they share the same ending vowel and consonant sounds. A word always rhymes with itself. LAMP STAMP Share the short “a” vowel sound Share the combined “mp” consonant sound RHYME SCHEME a pattern of rhyming words or sounds (usually end rhyme, but not always). Use the letters of the alphabet to represent sounds to be able to visually “see” the pattern. (See next slide for an example.) SAMPLE RHYME SCHEME A mighty creature is the germ, A Though smaller than the pachyderm. A His customary dwelling place B Is deep within the human race. B His childish pride he often pleases C -from “The Germ” by Ogden Nash END RHYME A word at the end of one line rhymes with a word at the end of another line A Hector the Collector Collected bits of string. -

Chapter 3 Stress and Prosody

Chapter 3 Stress and prosody 3.1 Stress Stress in Kokota is characterised by considerable variation. Some words with a particular segmental structure may be assigned stress on one pattern, while others with the same structure may be assigned stress on another pattern. A single lexeme may be assigned stress on one pattern by some speakers, and on another by others. This variation occurs even to the extent that a single lexeme may be assigned stress variably by a single speaker. In elicitation of citation forms a single speaker may give a lexeme three times, with two different stress patterns evident. There are, however, patterns to this variation. The variation results from three factors: irregular stress patterning on some lexemes resulting from the prosodic shadow of lost morphological complexity; the gradual regularisation of these irregularities; and an overall shift in the language's stress regime from moraic trochees to syllabic trochees. 3.1.1 Metrical stress and moraic theory The following discussion of stress is couched within the framework of metrical theory (see Hayes 1995:26- 31 for an introduction), which views stress as a rhythmic structure not as a feature, and moraic theory (Hayes 1995:48-54). This approach has been adopted as it appears to most adequately allow a description of stress assignment in Kokota. In syllabic stress syllables are assigned to feet of two syllables each. In moraic stress morae are parsed into feet of two morae each. Morae represent units of weight, in which each weight bearing element constitutes one mora. Onsets are not weight bearing units. -

Poetry Explication: Sonnet Forms

UIL Literary Criticism Poetry Explication: Sonnet Forms The sonnet is a poem almost invariably of fourteen lines and following, perhaps with variance, one of several set rhyme schemes. Petrarchan (Italian) sonnet abbaabba cdcdcd (or one of several two-rhyme or three-rhyme combinations without couplet) envelope sonnet abba cddc . Spenserian sonnet abab bcbc cdcd ee Shakespearean (English) sonnet abab cdcd efef gg Miltonic sonnet abbaabba cdccdc (no volta: octave and sestet "combined" Anglo-Norman sonnet abab cdcd efeffe abab cdcd efgefg ababcdcd efggfe hybrid sonnet various combinations of elements characterizing the Italian and the English forms French sonnet eleven-syllable lines caudate sonnet the Italian (usually) sonnet with an additional (usually six) lines: "tails" curtal sonnet a sonnet whose octave is curtailed to six lines and sestet is curtailed to four and a half lines variants tributes, no doubt, to the basic form Petrarchan sonnet (Italian sonnet) London, 1802 Milton! thou shouldst be living at this hour: England hath need of thee: she is a fen Of stagnant waters: altar, sword, and pen, Fireside, the heroic wealth of hall and bower, Have forfeited their ancient English dower Of inward happiness. We are selfish men; Oh! raise us up, return to us again; And give us manners, virtue, freedom, power. Thy soul was like a Star, and dwelt apart; Thou hadst a voice whose sound was like the sea: Pure as the naked heavens, majestic, free, So didst thou travel on life's common way, In cheerful godliness; and yet thy heart The lowliest duties on herself did lay. William Wordsworth Sonnet 90 She let her gold hair scatter in the breeze that twined it in a thousand sweet knots, and wavering light, beyond measure, would burn in those beautiful eyes, which are now so dim: and it seemed to me her face wore the colour of pity, I do not know whether false or true: I who had the lure of love in my breast, what wonder if I suddenly caught fire? Her way of moving was no mortal thing, but of angelic form: and her speech rang higher than a mere human voice. -

Proquest Dissertations

THE ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE VILLANELLE IN ENGLISH LITERATURE by Jean S. Moreau Thesis presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Ottawa in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. LIBRARIES * ''K S*^ 6l~Sity <rf Ottawa, Canada, 1975 M Jean S. Moreau, Ottawa, Canada, 1975, UMI Number: EC56066 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform EC56066 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis is prepared under the guidance of Professor Frank M. Tierney, Ph.D., of the Department of English of the University of Ottawa. The writer is greatly beholden to Dr. Tierney for his direction, scholarship, courtesy and unfailing patience. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page INTRODUCTION 1 I. - THE ORIGINS, DEFINITION AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE VILLANELLE IN FRANCE 3 1. Origins and Development of the Villanelle 3 2. Revival and Definition of the Villanelle in France .... 22 II. - THE VILLANELLE IN ENGLISH LITERATURE: THE INTRODUCTORY PERIOD 41 III. -

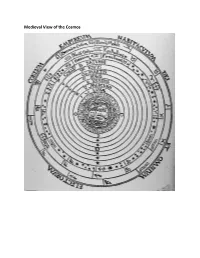

Medieval View of the Cosmos

Medieval View of the Cosmos Medieval World Map from 13th century Side-by-Side Comparison of Dante Translations Longfellow Translation Cary Translation Musa Translation Midway upon the journey of our life IN the midway of this our mortal Midway upon the road of our life I I found myself within a forest dark, life, found myself within a dark For the straightforward pathway had been lost. I found me in a gloomy wood, wood, for the right way had been astray missed. Ah! how hard a thing it Ah me! how hard a thing it is to say Gone from the path direct: and is to tell what this wild and rough and What was this forest savage, rough, and stern, e'en to tell dense wood was, which in Which in the very thought renews the fear. It were no easy task, how thought renews the fear! So bitter is it savage wild that death is little So bitter is it, death is little more; That forest, how robust and more. But in order to treat of the good But of the good to treat, which there I found, rough its growth, that there I found, I Speak will I of the other things I saw there. Which to remember only, my will tell of the other things that I have dismay seen there. I cannot I cannot well repeat how there I entered, Renews, in bitterness not far well recount how I entered it, so full So full was I of slumber at the moment from death. was I of slumber at that In which I had abandoned the true way. -

'The Feet of Love': Pagan Podophilia from A.C. Swinburne to Isadora

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 11 | 2015 Expressions of Environment in Euroamerican Culture / Antique Bodies in Nineteenth Century British Literature and Culture ‘The Feet of Love’: Pagan Podophilia from A.C. Swinburne to Isadora Duncan Charlotte Ribeyrol Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/6847 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.6847 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Charlotte Ribeyrol, “‘The Feet of Love’: Pagan Podophilia from A.C. Swinburne to Isadora Duncan”, Miranda [Online], 11 | 2015, Online since 21 July 2015, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/6847 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.6847 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. ‘The Feet of Love’: Pagan Podophilia from A.C. Swinburne to Isadora Duncan 1 ‘The Feet of Love’: Pagan Podophilia from A.C. Swinburne to Isadora Duncan Charlotte Ribeyrol In an article entitled “Le paganisme poétique en Angleterre” published in May 1867 in La Revue des Deux Mondes, the French literary critic Louis Etienne underlined the striking similarities between Keats’s and Swinburne’s pagan and sensual inspiration, deploring, however, the lack of manliness of their verses. Rather than emulating the virile ideal which the ancient Greeks had set so high, Keats and Swinburne seemed indeed to have favoured excessive “crying at the feet of Venus”―an effeminate whining tendency which Etienne detected “on almost every page” (316) of Swinburne’s Poems and Ballads, First Series (1866).