Planning for Appropriate Recreation Activities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corporate Registry Registrar's Periodical Template

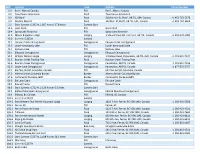

Service Alberta ____________________ Corporate Registry ____________________ Registrar’s Periodical SERVICE ALBERTA Corporate Registrations, Incorporations, and Continuations (Business Corporations Act, Cemetery Companies Act, Companies Act, Cooperatives Act, Credit Union Act, Loan and Trust Corporations Act, Religious Societies’ Land Act, Rural Utilities Act, Societies Act, Partnership Act) 101225945 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. Other 10978477 CANADA LTD. Federal Corporation Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2018 SEP 06 Registered Registered 2018 SEP 06 Registered Address: 2865 Address: 5009 - 47 STREET PO BOX 20 STN MAIN MADLE WAY NORTH WEST, EDMONTON (27419-1 TRK), LLOYDMINSTER ALBERTA, T6T 0W8. No: 2121414144. SASKATCHEWAN, S9V 0X9. No: 2121414847. 1133703 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 101259911 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. Other Registered 2018 SEP 05 Registered Address: 103, 201-2 Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2018 SEP 11 Registered STREET NE, SLAVE LAKE ALBERTA, T0G2A2. No: Address: 3315 11TH AVE NW, EDMONTON 2121411470. ALBERTA, T6T 2C5. No: 2121423640. 1178223 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 101289693 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. Other Registered 2018 SEP 04 Registered Address: 114-35 Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2018 SEP 04 Registered INGLEWOOD PARK SE, CALGARY ALBERTA, Address: 410, 316 WINDERMERE ROAD NW, T2G1B5. No: 2121411033. EDMONTON ALBERTA, T6W 2Z8. No: 2121411199. 1178402 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 102058691 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. Other Registered 2018 SEP 06 Registered Address: 1101-3961 Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2018 SEP 06 Registered 52ND AVENUE NE, CALGARY ALBERTA, T3J0J7. Address: 5016 LAC STE. ANNE TRAIL SOUTH PO No: 2121414698. BOX 885, ONOWAY ALBERTA, T0E 1V0. No: 2121414276. 1179276 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2018 SEP 13 Registered Address: SUITE 102059279 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. -

Canmore Nordic Centre Provincial Park Nordic Centre Area

Tear Sheet Canmore Nordic Centre Provincial Park March 2020 Mount Nordic Centre Area Map Canmore Lady MacDonald Bow Valley Wildland Nordic Centre Cougar Creek Canmore Canmore Nordic Centre Horseshoe 19.3 km Day Lodge Loop to Banff 1 To Banff Grotto Grassi Lakes 19.2 km Mountain Lake Louise Alpine Club (2706 m) Grassi Lakes of Canada Quarry 80 km Lake 742 Powerline Grotto Pond Grotto Canyon 1A 1A Whiteman’s Highline Pond Trail East Connector Goat Creek Ha Ling Peak (2407 m) Gap Lake 0.9 km Ha Ling 1 Lac High Peak Bow 1 Des Arcs Highline River Gap Rockies Trail Lake Old Camp Lac Des Arcs Three Sisters To Calgary, Hwy 40 & Kananaskis Country Banff Gate Bow Valley Wildland Mountain Resort Heart Mountain (2135 m) 7 km 742 Little Sister (2694 m) Pigeon Mountain (2394 m) High Middle Sister (2769 m) Rockies Windy Point (Closed Dec. 1 - June 15) Bow Valley Wildland Big Sister (2936 m) Goat Pond Smith-Dorrien/ Spray Lakes Road 7.3 km Skogan Pass Spray 742 Lakes West Centennial Ridge Wind West Driftwood (Closed April 1 - June 21) Pass Mount Windtower (2695 m) Spurling Creek Mount Collembola High (2758 m) Banff Rockies Mount National Park Spray Valley Lougheed (3105 m) Mount Allan (2819 m) 10.4 km Wind Mountain (3153 m) Boat Hiking Trail Launch Evan-Thomas Backcountry Parking Camping Bow Valley Wildland Centennial Bicycle Trail Information Sparrowhawk Ridge Camping Interpretive Area Trail Mount Sparrowhawk (3121 m) Cross-Country Snowshoeing Skiing Day Use Sleeping Mount Nestor Area Shelter (2974 m) Spray Lake Fishing Viewpoint Provincial Easy Trail 742 Ribbon Park Ribbon Peak Creek Provincial Park Intermediate Trail (2880 m) (Day Use) Difcult Trail Spray High Rockies Provincial Road (Closed Nov. -

Spray Valley Summer Trails

Legend Alberta/British Columbia Border B a ROADS n f POWER LINES f T HORSE/MOUNTAIN BIKING/HIKING ra il MOUNTAIN BIKING/HIKING TRAILS 6 G k e HIKING TRAILS ONLY m o r ( g UNDESIGNATED TRAILS o e n TRAIL DISTANCES 1.5 km t .. e o w w PARK BOUNDARY a y n ) 3 .5 k m Canmore Nordic G Centre o a Alpine Club t C 1 of Canada r e Grassi e k Lakes 1 9 .3 Grassi Goat Lakes km Creek to 3.5 km Banff Bow River Campground Bow River 742 Eau Claire KANANASKIS Sp 23 COUNTRY Driftwood Boat Launch Spray Lakes West BANFF NATIONAL PARK Sparrowhawk e id Spray Lake S t s e W S m i t h - D o r r i e n / S p r a y T r a i l Canyon Dam ek re r C B lle ry 9 km a B u n u B 1 km Guinns t l l Cr e Pass e Buller r e k ( M B Mountain a t. nf f P Buller ar Mount Pond k) Shark (Winter Only) ) Watridge k r Lake Mount a Shark P Watridge f f n Lake a 742 B 3.7 km ( s s a P Karst r Spring NORTH e Mt Engadine s 0.8 km i l l Lodge a P Peter Lougheed Provincial Park Spray Valley Spray Summer Trails Trails For Hikers, Mountain Bikers & Horseback Riders The way to the Spray Valley TRAIL ACCESS REMARKS Backcountry Permits WATRIDGE LAKE Mount Shark Day Use An easy trail to a beautiful emerald Backcountry permits are required to camp at any of the backcountry 3.7 km one way lake. -

Crowsnest Pass- Pincher Creek & Area

Calgary Reception Archive Copy Please Return -I - •• ."'T- .c•— v-fj'--- -r.=. Crowsnest Pass- Pincher Creek & Area USE THE YELLOW PAGE INDEX Area Code 403 AG August1982 yellow pages I I I d ) V J 2 BROCKET CNCP TELECOMMUNICATIONS To Send A Telegram Or Telepost (No Charge Dial) 1-800 222-6575 Pour Envoyer Un Telegramme Ou Teiepost BEAVER MINES— See Pincher Aucuns FraisOomposez 1-800 361-1872 Creek C P Air 505BurrardStVancouvef6C (No Charge Dial) 1-800 663-1444 Central Air Conditioning Vancouver - Cal Long Distance BELLEVUE— See Crowsnest Pass . (NoTol Charge)8 AskFor Zenith 08879 CITIZENS RESOURCE CENTRE BLAIRMORE— See Crowsnest Pass Bsmt20ia 30StBlairmofe Crowsnest Pass 562-2334 COMPUTER COMMUNICATIONS GROUP OF A BROCKET GT 3305 IBAvNLethbridgetNoChargeOia!) .. 1-800 552-8025 For dvlalM AOT Uttlngc Crowlodge Grocery Store 965-3838 •MPagc'l" . Dowshoe Francis 965-2376 SERVICE CALLS ED'S SERVICE STATION t965-3872 HRECT MSTANCE DUUNG 1 1965-3913 LONGOiSTANCE DUUJNG 0 Energesis-Control Systems Ltd Laogley BC- Call Long MtECTORY ASSISTANCE FOR Distance (No Tol Charge) 8 Ask For Zenith 08897 Local Numbers & calling Environment (ktuncil (}f Alberta .Cal Long O'lsiance (No Td Charge) 8 Ask For Zenith 06075 areas listed below 1 + 411 Four Horns Ed 965-2134 Numbers In other Alberta Locations (No Tol Charge) 1 + 555-1212 FUU GOSPEL CHURCH 965-3742 Numbers outside Alierta Gendarmerie Royale Du Canada (No Tol Charge) 659 Main St Pincher Creek 627-4424 STIN'YA Pas De Reponse Composez'0' (Appel Sans Frais) 1-FArea Coder- 555-1212 El Demandez Zenith -

Mastertd2019 V1.Pdf

MM Location Type Address Phone Number 0.0 Banff, Alberta Canada POI Banff, Alberta Canada 0.0 Townhouse Groceteria Food Townhouse Groceteria 0.0 IGA Banff Food 318 Marten St, Banff, AB T1L 1B4, Canada +1 403-762-5378 0.0 Nesters Market Food 122 Bear St, Banff, AB T1L 1A1, Canada +1 403-762-3663 2.1 Start Summit: 6,365 ft, 1,807 ft over 37.8 miles Summit Start 14.9 Goat Pond POI Goat Pond 19.4 Spray Lake Reservoir POI Spray Lake Reservoir 31.0 Mount Engadine Lodge Lodging 1 Mount Shark Rd, Canmore, AB T0L, Canada +1 403-678-4080 40.0 Summit: 6,365 ft Summit 45.7 Canyon Creek Campground Campground Canyon Creek Campground 45.9 Lower Kananaskis Lake POI Lower Kananaskis Lake 46.1 Spillway Lake POI Spillway Lake 50.1 Elkwood Campground Campground Elkwood Campground 50.4 William Watson Lodge Lodging 1 Watson Road, Kananaskis, AB T0L 2H0, Canada +1 403-591-7227 52.5 Boulton Creek Trading Post Food Boulton Creek Trading Post 52.6 Boulton Creek Campground Campground Kananaskis, AB T0L, Canada +1 403-591-7226 52.9 Lower Lake Campground Campground Kananaskis, AB T0L, Canada +1 877-537-2757 57.1 Elk Pass, British Columbia, Canada POI Elk Pass, British Columbia, Canada 57.2 Alberta British Columbia Border Border Alberta British Columbia Border 57.6 Continental Divide 6,368ft Border Continental Divide 6,368ft 59.9 Elk Lake Cabin Campground Elk Lake Cabin 98.4 Round Prairie POI Round Prairie 98.5 Start Summit: 6,722 ft, 2,526 ft over 5.5 miles Summit Start 99.4 Elkford Municipal Campground Campground Elkford Municipal Campground 99.4 Elkford, BC Canada -

SRV 1402 Regio CAN Web.Pdf

Exciting New Events 1 In Canada, many new and exciting Swiss and Swiss-related events are being planned and prepared for as you are reading this. The beau- tiful mountain town of Golden is in full gear organizing its first an- nual BC Mountain Festival which takes place May 18th & 19th. De- dicated to the celebration of the rich history and pioneering efforts Photo Golden Museum Edelwiss of the Swiss Mountain Guides in the Ro- Editorial Village then and ckies, and honoring their outstanding Dear Readers and Friends across Canada and around the World: now–Feuz contributions to the exploration and de- It is with delight that I’ve come to realize that our news not only in- family ca. 1914 velopment of the mountain culture, the form and entertain, but also connect people across the world! We festival features interactive talks and are evidently read far beyond Canada and Swit- presentations, authentic Swiss food and zerland as I have learned from recent reader feed- entertainment, and guided tours through back. It is also a pleasure for me to work together Edelweiss village built in 1912 by CP rail with you all—members of Swiss Societies, Official Photo Joanne Sweeting for the Swiss Guides and their families. Representations and other individuals and organi- An interesting and fun Victoria Day long-weekend event for which zations in the production of our Regional News! you find Tourism Golden’s schedule on page 2. Making this an informative cross-section of Swiss news in our beau- Many Swiss organization celebrate an anniversarythis year and tiful adopted home land Canada, I realize how much diversity, cre- are thus planning special events. -

Residential Flat Tax Court of Revision Meeting to Be Held at Municipal Hall 270 City Centre on Monday, April 26, 2021 at 7:00 P.M

1 To provide input on an item on the agenda, please call (250) 632-8900 or email [email protected] by 4:30 p.m. on Monday, April 26, 2021. RESIDENTIAL FLAT TAX COURT OF REVISION MEETING TO BE HELD AT MUNICIPAL HALL 270 CITY CENTRE ON MONDAY, APRIL 26, 2021 AT 7:00 P.M. 1. Court of Revision for Flat Tax Page 3 COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE MEETING TO BE HELD AT MUNICIPAL HALL 270 CITY CENTRE ON MONDAY, APRIL 26, 2021 FOLLOWING THE RESIDENTIAL FLAT TAX COURT OF REVISION 1. Call to Order 2. Public Input / Questions on Agenda Items 3. Media Inquiries - For Clarification Only 4. New Business/Adoption of Agenda Page 5 5. Delegation – Mount Elizabeth Cycling Association Page 99 6. Report – Amend Accessory Building provisions of the Kitimat Municipal Code Page 103 7. Report – Union of British Columbia Municipalities Local Government Development Approvals Program Page 113 8. Report – BC Hydro Level 3 Charging Station Location 2 Page 119 9. Report – Student Fare Transit Pilot Program Page 123 10. Report – Leisure Access Program Subsidy Page 129 11. Report – Provincial Travel Restrictions Campground Bookings SPECIAL MEETING OF COUNCIL MEETING TO BE HELD AT MUNICIPAL HALL, 270 CITY CENTRE ON MONDAY, APRIL 26, 2021 FOLLOWING THE COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE 1. Call to Order 2. Public Input / Questions on Agenda Items 3. Media Inquiries - For Clarification Only 4. New Business/Adoption of Agenda Page 133 5. Bylaw – Adoption - Solid Waste Collection and Disposal Amendment Bylaw No. 1997, 2021 Page 135 6. Report – Mutual Aid Agreement – City of Terrace and Regional District of Kitimat-Stikine (Thornhill Fire Protection) CLOSED MEETING TO BE HELD FOLLOWING THE SPECIAL MEETING OF COUNCIL ON MONDAY, APRIL 26, 2021 Call for Closed New Business Items and Agenda Changes Moved by , Seconded by , THAT the agenda be adopted and Council deal with these matters in closed session. -

2015-16 Annual Report FINAL

The Friends of Kananaskis Cooperating Society Annual Report April 1, 2015 – March 31, 2016 The Friends of Kananaskis Cooperating Society Annual Report April 1, 2015 – March 31, 2016 Table of Contents! Board and Staff, March 2015 – March 2016 ....................................................................... 3! 2015: Stretching our Wings ................................................................................................. 4! 2015 – 2016 Key Accomplishments ...................................................................................... 5! 2015 – 2016 Business Plan ................................................................................................... 6! Chair’s Report .................................................................................................................... 8! Governance Subcommittee Report .................................................................................... 9! Program Coordinator Report ............................................................................................ 10! Subcommittee Reports: ..................................................................................................... 13! Trail Care ................................................................................................................................... 13! Communications and Marketing ................................................................................................. 16! Human Resources ..................................................................................................................... -

October Newsletter

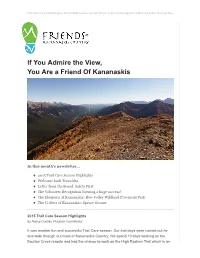

Fall colours are basically gone, but beautiful weather remains for you to get out and enjoy the wilderness before the snow flies. If You Admire the View, You Are a Friend Of Kananaskis In this month's newsletter... 2015 Trail Care Season Highlights Welcome back TransAlta Letter from the Board: Safety First The Volunteer Recognition Evening a huge success! The Elements of Kananaskis: Bow Valley Wildland Provincial Park The Critters of Kananaskis: Spruce Grouse 2015 Trail Care Season Highlights by Nancy Ouimet, Program Coordinator It was another fun and successful Trail Care season. Our trail days were carried out far and wide through out most of Kananaskis Country. We spend 10 days working on the Boulton Creek reroute and had the chance to work on the High Rockies Trail which is an exciting new addition to the Smith-Dorrien corridor. Season highlights include: 38 Trail Care days 1,814 Volunteer-hours recorded 167 Different individuals were engaged 330 Volunteer slots were filled 15 Volunteer crew leaders lead groups 1,353 Members on mailing list Trail Care projects were undertaken in 13 different locations, they include: Alberta Parks Galatea Creek Trail (4 days) Canmore Nordic Centre (5 days) Boulton Creek Trail (10 days) Ribbon Creek Trail (1 day) Mount Shark Ski Trail (1 day) Mist Creek Trail (1 day) Elk Pass Trail (1 day) ESRD - Backcountry Trail Flood Rehabilitation Program Diamond T Loop (1 Day) Prairie Creek Trail (5 days) Jumping Pound Ridge (5 days) High Rockies Trail Project Sparrowhawk (1 day) Buller Mountain (2 day) Highway 40 Clean Up (1 day) A big THANK YOU to the outstanding volunteers and crew leaders for their time and effort improving Kananaskis Country trails. -

Touring & Exploring Guide

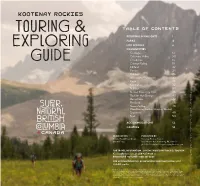

kootenay rockies TouRinG & table of contents REGIONAL HIGHLIGHTS 1 PARKS 4 EXPlOriNg HOT SPRINGS 6 COMMUNITIES Castlegar 12 Columbia Valley 30 GuiDE Cranbrook 16 Creston Valley 19 Elkford 22 Fernie 24 Golden 26 Invermere / Panorama 30 Kaslo 39 Kimberley 32 Nakusp 34 Nelson Kootenay Lake 36 distribution. for free in Canada Printed Radium Hot Springs 40 Revelstoke 42 Rossland 45 Slocan Valley 48 (New Denver, Sandon, Silverton, Winlaw) Sparwood 49 Trail 50 BC / Destination Medig by Kari Trail; / Rockwall Park National Kootenay Photo: ACCOMMODATIONS 52 CAMPING 55 PRODUCTION: PUBLISHED BY: Brenda MacGillivray Design Kootenay Rockies Tourism Mitchell Press 1905 Warren Ave, Kimberley, BC V1A 1S2 ph 250-427-4838 [email protected] FOR TRAVEL INFORMATION , CONTACT KOOTENAY ROCKIES TOURISM KootenayRockies.com, ph 250-427-4838 or BROCHURE HOTLINE 1-800-661-6603 FOR ACCOMMODATIONS, RESERVATIONS AND TRAVEL IDEAS VISIT HelloBC.com/kr © 2016 - Kootenay Rockies Tourism (the”Region”). All rights reserved. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited. This Guide does not constitute, and should not be construed as, an endorsement or recommendation of any carrier, hotel, restaurant or any other facility, attraction or activity in British Columbia, for which neither Destination BC Corp. nor the Region assumes any responsibility. Super, Natural British Columbia®, Hello BC®, Visitor Centre and all associated logos/trade-marks are trade-marks or Official Marks of Destination BC Corp. Admission fees and other terms and conditions may apply to attractions and facilities referenced in this Guide. Errors and omissions excepted. 11 11 Red Deer 93 11 2 22 1 2 Pacific Mountain Time Time BRITISH COLUMBIA KOOTENAY Vancouver ROCKIES Calgary Kinbasket L. -

Rossland Mountain Bike Visitor Study 2011

RESEARCH, PLANNING & EVALUATION GOLDEN MOUNTAIN BIKE VISITOR STUDY 2011 RESULTS December, 2012 Research, Planning & Evaluation Tourism British Columbia Ministry of Jobs, Tourism and Skills Training 3rd Floor-1803 Douglas St. Victoria, British Columbia V8W 9W5 Web: http://www.jtst.gov.bc.ca/research/ Email: [email protected] Phone: 250-387-1567 Golden Mountain Bike Visitor Study - Summer 2011 Acknowledgements The 2011 Golden Mountain Bike Visitor Study was a comprehensive survey of mountain bike travellers to Golden between July 1 and September 5, 2011. The Golden Mountain Bike Visitor Study was a partnership between Tourism British Columbia (part of the Ministry of Jobs, Tourism and Skills Training), Western Mountain Bike Tourism Association and Tourism Golden. Partial funding for the data collection was provided by the Town of Golden Resort Municipality Fund. Tourism British Columbia and partners would like to gratefully acknowledge the Recreation Sites and Trails Branch for providing trail counters, the Golden Cycling Club for the management of trail counters and Kicking Horse Resort in Golden that assisted the project by providing access for interviewers. We would also like to thank Kicking Horse Country Chamber of Commerce, Derailed Sports, and Summit Cycle for their support and feedback. Research, Planning and Evaluation, Tourism British Columbia i Golden Mountain Bike Visitor Study - Summer 2011 Executive Summary The purpose of this study was to develop a profile of mountain bikers who visited Golden in terms of their traveller and trip characteristics. Travellers were interviewed at trailheads while mountain biking on one of the four trail networks in Golden (Kicking Horse Mountain Resort, Moon Raker at Cedar Lake , Mount 7 at Reflection Lake, and CBT Mainline Trail at Columbia Bridge). -

Area Code 403 D\A

Calgary Archive CoPV Please J S \*h_ u*, Q_ li. I'(¥i3^w Area Code 403 D\A yellQw pages C P Air 505 BurrardSt Vancouver BC(No Lufthansa German Airlines Toronto - Cal 2 BROCKET ChargeDial) 1-800 663-1444 Long Distance (No Tol Ctiarge) A Ask CANADIAN WESTERN NATURAL For Zenith 02520 GAS CO LTD Matthies Arthur 157MountainSt 965-7235 BEAVER MINES— See NATURAL GAS SERVICE MEDICAL CLINIC (ASSOCUVTE) Pincher Creek 245 24 St (Cdect) (Fort Madeod) 553-3885 964KettlesSt Pincher Creek 627-3321 Career Development Peigan Band Native Counselling Service 965-3933 BOX7D 965-3863 North Peigan D 965-2431 BELLEVUE— See Ore Central Air ConcBtioning Vancouver - Cal North Peigan Fred 965-3957 Pass long Distance (No Tol Otarge) A Ash North Peigan i 965-3781 For Zenith 08879 North Peigan Manford 965-3804 North Peigan Rebecca 965-2362 BLAIRMGRE— See CITIZENS RESOURCE CENTRE 2675 21AV North Peigan Woodrow 965-3868 Crowsnest Pass Biaitmore Crowsnest Pass 562-2334 Northwest AirOhes Inc- CalLong Distance (No Tol Charge) A Ask For Zenith 07566 COMPUTER COMMUNICATIONS Nova An Alberta Corporation BROCKET GROUP OF A G T 24 Hr Emergency Service For dotailod AQT LMingt: 3305 18AvMethbridge(NoCharge •OO PiQO **1" . Cal Colect Calgary 252-8821 DiaQ 1-800 552-8025 OLD MAN RIVER CULTURAL SERVICE CAUS ED'S SERVICE STATION ^965-3872 MtECT DISTANCE DUUNG 1 iM5-3913 CENTRE 965-3939 LONG DISTANCE DIALMG 0 Energesis-Contrd Systems Ltd Langley B Old Man River Projects 965-3774 DIRECTORY ASSISTANCE FOR C- CU Long Distance (No Tol Ctiarge) A Ask Pacific Western Airlines - CauLong Local Numbers ft caBng For Zenith 08897 Distance (No Tol (3iarge) A Ask areas listed below 1 + 411 Envirofim^ CauncB Of Alberta -Cal Long For Zenith 66099 Numbers in other Alierta Distance (No Tol Charge) A Ask Pard Alen 965-2189 Locstions Fot Zenith 0607S PASS HERALD CNoTol Charge).