Health Sciences Center Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter VOL

The Obstetrical Society of Philadelphia To embrace our legacy, foster collegiality, and share expertise to improve the health of women in Philadelphia and beyond OCTOBER 2018 Newsletter VOL . 46, NO. 2 President’s Message Upcoming Lecture The Obstetrical Society of Philadelphia; Is It Worth Our Time and Effort? PETER F. SCHNATZ, D.O. As we celebrate our sesquicentennial anniversary and spend time focusing on our accomplishments and achievements over the years, it causes us to Thursday, November 15, 2018, 6:00 PM look forward to the future of our organization. Many state OBGYN societies have stopped functioning over the past decade or so, for a variety of reasons, including fi nances, time constraints, the busyness of our personal and professional lives, and “Osteoporosis: an assortment of other competing factors. Before strategizing ways to be successful Update and Overview” this year, and in the coming years, it is important to ask the following question; “Is the society truly of value or are we simply keeping it going for the sake of nostalgia?” We hope that you will be able to join us While the acquisition of medical knowledge and guest presenters are at the core of for our October meeting, when Michael what we do, this can be acquired through a variety of mechanisms and in and of itself McClung, M.D., of Oregon Osteoporosis Center will discuss osteoporosis. is probably not worth sustaining the organization. As I assess our society, here are some of the core values and reasons I see to spend our time, fi nances, and resources in See page 3 for details. -

1 Skull 1970 Temple University School of Medicine Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Library Temple UnW«*J CenW Health Sciences TEMPLE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE Temple University Hospital Library Temple University Health Sciences Center September 6,1966-June 14,1970 four years is time... four years is work.. four years is happiness TEMPLE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MEQWNE ADMINISTRATION OFFICES OFFICE OF THE OEM 1ST FL NORTH LIBRARIAN RMEtO OIR STUDENT LABORATORIES STUDENT ACTIVITIES LIBRARY 2ND FLOOR LECTURE ROOM A » * ' "• CASE STUDY RM A » B 1ST FL *£** RECEJVIH6 CLERK "'•:.:/"•." - our years is ^guC^^jMiwfeggiiwwiiiwiwawuitiiiiii change... Textbook of PEDIATRICS NELSON VAUGHAN i?«!^ •>/"•:'{€: - ft,.' •• McKAY I«?V, j- s ... V* . • !*« * mi • Ill NtNTMISmOH ILLJ EIGHTH EDITION •*'"<••' ~Z'A'7,~~;™Z?'rZrX.'V?i^:'' OAT T*\ T T^ in T> P N-ai»wy«wiww'<yiwwpitfea|b *• iMpm 4 :\i I II* I .:«. #3 % * but for the class of 1970, four years is just the beginning. ,-, ••-• 1 skull 1970 temple university school of medicine Philadelphia, Pennsylvania S93p$\f* ***** » ,\*\ S %* 5i^' •\v.. table of BwA. contents Dedication Carson D. Schneck, M.D., Ph.D i?:.^r fflfcfc Our four years Whither the class of 1970? by Alan G. Giberson, M.D. Seniors Hw Senior Directory Faculty and Administration Underclassmen Organizations Skull Staff -1970 Patrons and Advertising dedication Carson D. Schneck, M.D., Ph.D, Associate Professor of Anatomy It is apparent to any member of the audience that Carson Schneck loves to teach. He attacks the subject of the hour with enthusiasm and precision, creating in his students a basic understanding of certain com plex anatomical relationships. In time, the varied facets of the problem discussed fall into perspective and are absorbed by all present. -

Tower Health Overview

For the Period Ended June 30, 2020 Unaudited Quarterly Disclosure 0 Tower Health Overview Tower Health (“Tower Health” or the “System”) is a Pennsylvania nonprofit corporation that serves as the parent organization of seven acute care hospitals, an inpatient behavioral health facility, and related facilities that have formed an integrated healthcare system located in the Counties of Berks, Chester and Montgomery, Pennsylvania and the City of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Brandywine Hospital in Coatesville (171 licensed beds); Chestnut Hill Hospital in Philadelphia (148 licensed beds); Jennersville Hospital in West Grove (63 licensed beds); Phoenixville Hospital in Phoenixville (137 licensed beds); Pottstown Hospital in Pottstown (232 licensed beds); and Reading Hospital in Reading (738 licensed beds, including 62 beds at Reading Rehabilitation Hospital at Wyomissing) St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children in Philadelphia (188 licensed beds) – as part of a 50/50 Joint Venture between Tower Health and Drexel University On July 14, 2020, Tower Behavioral Health, a 144-bed inpatient facility and ambulatory campus opened under a joint venture with Acadia Healthcare. Tower Health Medical Group - Network of more than 128 primary care and specialty care locations, that includes 890 physicians and 411 Advanced Practice Providers. Tower Health Partners - Clinically Integrated Network with more than 3,096 participating providers Tower Health UPMC Health Plan Tower Health Urgent Care - Tower Health acquired 19 urgent care locations from Premier Urgent Care on December 1, 2018. According to the Philadelphia Business Journal, the acquisition made Tower Health the largest operator of urgent care centers in the metropolitan Philadelphia area Tower Health at Home- Since July 1, 2019 home health services have grown 21% to a daily census of 386 patients and hospice services have grown 22% with an average daily census of 44 patients. -

Berks County Industrial Development Authority

NEW ISSUE – BOOK-ENTRY ONLY Ratings: S&P: A Moody’s: A3 Fitch: A In the opinion of Stevens & Lee, P.C. (“Bond Counsel”), assuming continuing compliance by the Authority and the Obligated Group with certain covenants to comply with provisions of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the “Code”), and all regulations applicable thereunder, interest on the 2017 Bonds is not includable in gross income under Section 103(a) of the Code and interest on the 2017 Bonds is not an item of tax preference for purposes of the federal, individual or corporate alternative minimum taxes; although Bond Counsel observes that such interest is included in adjusted current earnings when calculating the corporate alternative minimum taxable income; also see “TAX EXEMPTION AND OTHER TAX MATTERS” herein for a brief description of some of the other provisions of the Code affecting the purchasers and holders of the 2017 Bonds. In the opinion of Bond Counsel, under the laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (the “Commonwealth”), the 2017 Bonds and interest on the 2017 Bonds shall be free from taxation for state and local purposes within the Commonwealth, but this exemption does not extend to gift, estate, succession or inheritance taxes or any other taxes not levied directly on the 2017 Bonds or the income therefrom. Under the laws of the Commonwealth, profits, gains or income derived from the sale, exchange or other disposition of the 2017 Bonds, are subject to state and local taxation within the Commonwealth. $590,500,000 BERKS COUNTY INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT -

Ready; Comprehensive Stroke Center

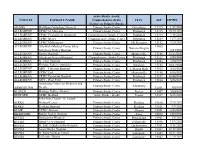

Acute Stroke -ready; COUNTY FACILITY NAME Comprehensive stroke CITY ZIP EXPIRES Center; or Primary Stroke ADAMS WellSpan Gettysburg Hospital Primary Stroke Center Gettysburg 17325 1/22/2024 ALLEGHENY UPMC St. Margaret Primary Stroke Center Pittsburgh 15215 10/20/2022 ALLEGHENY UPMC Presbyterian Shadyside Comprehensive Stroke Center Pittsburgh 15213 7/18/2021 ALLEGHENY UPMC Mercy Comprehensive Stroke Center Pittsburgh 15219 12/7/2021 ALLEGHENY UPMC McKeesport Primary Stroke Center Mc Keesport 15132 7/20/2021 ALLEGHENY Alle-Kiski Medical Center d/b/a/ 15065 Primary Stroke Center Natrona Heights Allegheny Valley Hospital 3/14/2021 ALLEGHENY Forbes Hospital Primary Stroke Center Monroeville 15146 11/17/2022 ALLEGHENY Allegheny General Hospital Comprehensive Stroke Center Pittsburgh 15212 3/20/2021 ALLEGHENY St. Clair Hospital Primary Stroke Center Pittsburgh 15243 2/24/2023 ALLEGHENY Heritage Valley - Swickley Primary Stroke Center Swickley 15143 10/17/2021 ALLEGHENY AHN - Jefferson Hospital Primary Stroke Center Jefferson Hills 15025 3/13/2023 ALLEGHENY UPMC East Primary Stroke Center Monroeville 15146 6/16/2023 ALLEGHENY UPMC Passavant Hospital Primary Stroke Center Pittsburgh 15237 10/28/2022 ALLEGHENY AHN - West Penn Primary Stroke Center Pittsburgh 15224 5/26/2021 Armstrong Center for Medicine and Primary Stroke Center Kittanning ARMSTRONG Health 16201 3/8/2022 BEAVER Heritage Valley - Beaver Primary Stroke Center Beaver 15009 10/4/2021 BEDFORD UPMC Bedford Acute Stroke - Ready Everett 15537 6/25/2021 Penn State Health - St. Joseph BERKS Medical Center Primary Stroke Center Reading 19610 7/24/2022 BERKS Reading Hospital Primary Stroke Center Reading 19611 9/9/2021 BLAIR UPMC Altoona Primary Stroke Center Altoona 16601 5/15/2023 BRADFORD Robert Packer Hospital Primary Stroke Center Sayre 18840 12/5/2022 BUCKS Doylestown Hospital Primary Stroke Center Doylestown 18901 3/5/2021 BUCKS Grand View Hospital Primary Stroke Center Sellersville 18960 11/4/2022 BUCKS St. -

Internship and Residency Matches Class of 2011

Internship and Residency Matches Class of 2011 Match Type Specialty Site, City and State Allopathic Internship Traditional Rotating Allegheny General Hospital Pittsburgh, PA 1 Medical College of Georgia Augusta, GA 1 Summa Health System Akron, OH 1 University of Florida Collegeof Medicine Jacksonville, FL 2 University of North Dakota Grand Forks, ND 1 Transitional Year Henry Ford Health System Detroit, MI 1 New Hanover Regional Medical Center Wilmington, NC 1 St. Elizabeth Health Center Youngstown, OH 1 Allopathic Residency Anesthesiology Albany Medical Center Albany, NY 1 Cleveland Clinic Foundation Avon, OH 1 Dallas Southwest Medical Ctr Dallas, TX 1 Hershey Medical Center Hershey, PA 1 Jackson Memorial Hospital Miami, FL 2 Loyola University Maywood, IL 1 Shands Hosp., U of Florida Gainesville, FL 1 UPMC Education Program Pittsburg, PA 2 Emergency Medicine Akron General Medical Center Akron, OH 2 Albert Einstein Medical Center Philadelphia, PA 1 Baystate Medical Center Springfield, MA 2 Detroit Receiving Hospital Detroit, MI 1 Florida Hospital East Orlando Orlando, FL 1 Hershey Medical Center Hershey, PA 1 John Peter Smith Hospital Fort Worth, TX 1 Michigan State University Kalamazoo, MI 2 Summa Health System Akron, OH 1 Texas A&M - Scott-White Temple, TX 1 University of Illinois Collegeof Medicine-Peoria Peoria, IL 1 University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics Iowa City, IA 1 York Hospital York, PA 3 Family Medicine Bayfront Medical Center St. Petersburg, FL 1 Broward General Medical Center Fort Lauderdale, FL 1 Community Hospitals Indianapolis, -

Directory of Physicians & Health Care Resource Guide

2016-2017 BERKS MEDICAL SOCIETY 2016-2017 BERKS COUNTY MEDICAL SOCIETY 2016-2017 DIRECTORY OF PHYSICIANS & HEALTH CARE RESOURCE GUIDE DIRECTORY OF PHYSICIANS OF DIRECTORY No Charge Delivery! In-Home Senior Care SERVICES Seniors want to live safely and Personal Care: independently in their own homes…with •Bathing / Dressing •Mobility Assistance Comfort Keepers® professional in-home •Transferring / care…they can! Positioning •Toileting & Together we can: Incontinence Care •Feeding • Reduce hospitalizations •Dementia Care • Assure continuation of individualized •End of Life Care care plans Companionship • Encourage recommended diet Services: •Medication Reminders and exercise •Meal Preparation • Support the well-being of seniors •Laundry •Light Housekeeping •Grocery Shopping / Serving Berks County Since 2001 Errands •Incidental Transportation •24 hour care •Respite & Relief for Family Call to discuss your patient's needs (610) 678-8000 ComfortKeepers.com/BerksCounty-PA Award-Winning Answering Services Advantage TeleMessaging, Inc. knows that running a medical practice in today’s fast-paced, competitive environment is tough enough. Since 1994, we have provided affordable and professional telephone answering services, and HIPAA/HITECH-compliant call management solutions that give you the competitive advantage you need for your practice to succeed! Call us today at 610.372.5551 to find out how we can improve your business! www.AdvantageTeleMessaging.com BERKS COUNTY MEDICAL SOCIETY 2016-2017 DIRECTORY OF PHYSICIANS OFFICERS AND STAFF 2016 President Andrew R. Waxler, MD President Chair, Executive Council D. Michael Baxter, MD 2016 Secretary Greg Wilson, DO 2016 Treasurer Michael Haas, MD Immediate Past President Lucy L. Cairns, MD Executive Director T. J. Huckleberry Executive Assistant Betsy Ostermiller BERKS COUNTY MEDICAL SOCIETY 1170 Berkshire Blvd., Wyomissing, PA 19610 Phone: 610-375-6555 l Fax: 610-375-6535 [email protected] l www. -

Accredited Primary Stroke Centers

Accredited Primary Stroke Centers County Facility Name City Zip Montgomery Abington Memorial Hospital Abington 19001 Armstrong ACMH – Armstrong County Kittanning 16201 Philadelphia Albert Einstein Med. Center Philadelphia 19141 Allegheny Allegheny General Hospital Pittsburgh 15212 Bucks Aria Health – Bucks County Campus – Bucks County Langhorne 19047 Philadelphia Aria Health – Frankford Campus – Philadelphia County Philadelphia 19124 Philadelphia Aria Health – Torresdale Campus – Philadelphia County Philadelphia 19114 Chester Brandywine Hospital Coatesville 19320 Mercer Co., NJ Capital Health Medical Center – Hopewell New Jersey – Mercer Co., New Jersey Pennington NJ 8534 Mercer Co., NJ Capital Health Regional Medical Center – Trenton New Jersey – Mercer Co., NJ Trenton NJ 8638 Franklin Chambersburg Hospital Chambersburg 17201 Chester Chester County Hospital – Chester County West Chester 19380 Philadelphia Chestnut Hill Hospital Philadelphia 19118 Cambria Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center Johnstown 15905 Delaware Crozer Chester Medical Center, Taylor Ridley Park 19078 Delaware Crozer Chester Medical Center, Upland Upland 19013 Delaware Delaware County Memorial Hospital Drexel Hill 19026 Bucks Doylestown Hospital Doylestown 18901 Northampton Easton Hospital Easton 18042 Montgomery Einstein Medical Center Montgomery East Norriton 19403 Lancaster Ephrata Community Hospital Ephrata 17522 Union Evangelical Community Hospital Lewisburg 17837 Allegheny Forbes Hospital Monroeville 15146 Lackawanna Geisinger Community Medical Center – Scranton -

Keystone HMO Proactive Hospital Tier Placements

Keystone HMO Proactive hospital tier placements Tier 1 – Preferred $ Pennsylvania New Jersey Bucks Montgomery Burlington Aria Health — Bucks County Campus Abington Memorial Hospital Deborah Heart & Lung Center Doylestown Hospital Albert Einstein Medical Center — Virtua Willingboro Hospital Grand View Hospital Montgomery Campus Camden Lower Bucks Hospital Holy Redeemer Hospital and Medical Center Cooper Hospital University Medical Center Rothman Orthopaedic Specialty Hospital Lansdale Hospital St. Luke’s Health Network — Quakertown Campus Suburban Community Hospital Mercer Tower Health — Pottstown Memorial Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital Chester Medical Center at Hamilton Chester County Hospital St. Francis Medical Center Tower Health — Brandywine Hospital Philadelphia Tower Health — Jennersville Regional Hospital Albert Einstein Medical Center Salem Tower Health — Phoenixville Hospital Albert Einstein Medical Center — Memorial Hospital of Salem County Delaware Germantown Campus Warren Crozer-Chester Medical Center Aria Health — Frankford Campus Hackettstown Community Hospital Delaware County Memorial Hospital Aria Health — Torresdale Campus Springfield Hospital Jeanes Hospital Taylor Hospital Roxborough Memorial Hospital Tower Health — Chestnut Hill Hospital Lehigh Wills Eye Hospital St. Luke’s Health Network — Allentown Campus St. Luke’s Health Network — Bethlehem Campus Tier 2 – Enhanced $$ Pennsylvania New Jersey Delaware Philadelphia Camden New Castle Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Virtua Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital A.I. DuPont Hospital for Children Fox Chase Cancer Center Gloucester St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children Inspira Medical Center — Woodbury Shriner’s Hospital for Children Tier 3 – Standard $$$ Pennsylvania New Jersey Berks Montgomery Burlington Salem St. Joseph Medical Center Main Line Health — Bryn Mawr Virtua Marlton Hospital Inspira Medical Center — Elmer Tower Health — Reading Hospital and Hospital Virtua Memorial Hospital Warren Medical Center Main Line Health — Lankenau Camden St. -

Nursing Program

NURSING PROGRAM RHSchoolofHealthSciences.org Reading Hospital School of Health Sciences Offers a Registered Nurse diploma program that builds on 131 years of experience in educating women and men for an exciting career in the nursing profession. Graduates have secured positions at Reading Hospital and elsewhere in our community, as well as around the world. The Nursing Program is based within the School of Health Sciences, located near the hospital’s main campus in West Reading, Pennsylvania. The Program admits new classes in August. Accredited by the Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing, the Nursing Program offers education focusing on knowledge and skills required for entry level RN practitioners and includes clinical experiences in specialty areas such as pediatrics, maternity, oncology, and intensive care. The Nursing Program is affiliated with a university college vendor. Physical sciences, biological sciences, behavioral sciences, and English composition are taught at the School of Health Sciences by University faculty. This affiliation enables Nursing Program graduates to qualify for RN-BSN completion programs. The relationship between schools to this agreement is that of independent contractors and not construed to constitute a partnership, joint venture, or any other relationship other than that of independent contractors. Financial aid, tuition, fees, and all financial aspects of attending the Nursing Program at Reading Hospital School of Health Sciences are administered through Reading Hospital School of Health Sciences. Accreditations and Approvals Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing (ACEN) The diploma nursing program at Reading Hospital at the Reading Hospital School of Health Sciences located in Reading, PA is accredited by the: Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing (ACEN) 3390 Peachtree Road NE, Suite 1400, Atlanta, GA 30326 Phone: 404-975-5000 The most recent accreditation decision made by the ACEN Board of Commissioners for the diploma nursing program is Continuing Accreditation. -

UPMC Inside Advantage Network Listing

UPMC Inside Advantage Network listing of UPMC Health Plan participating Effective March 2021 hospitals for commercial employer group plans Level 1 Hospitals and Facilities Lycoming Level 2 Hospitals and Facilities UPMC Muncy Allegheny Allegheny UPMC Williamsport Curahealth Pittsburgh Heritage Valley Health System – UPMC Williamsport Divine Select Specialty Hospital – McKeesport Heritage Valley Kennedy Providence Campus Select Specialty Hospital – Heritage Valley Health System – Pittsburgh UPMC McKean Heritage Valley Sewickley UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh Bradford Regional Medical Center Jefferson Hospital UPMC East UPMC Kane LifeCare Behavioral Health Hospital of UPMC Hillman Cancer Center Pittsburgh Mercer UPMC Magee-Womens Hospital Grove City Medical Center LifeCare Hospitals of Pittsburgh at UPMC McKeesport UPMC Horizon – Greenville Main Campus UPMC Mercy UPMC Horizon – Shenango Valley St. Clair Hospital UPMC Montefiore The Children’s Home of Pittsburgh UPMC Passavant – McCandless Potter The Children’s Institute UPMC Presbyterian UPMC Cole Armstrong UPMC St. Margaret Somerset Armstrong County Memorial UPMC Shadyside UPMC Somerset Hospital UPMC Western Psychiatric Hospital Tioga Beaver Bedford UPMC Wellsboro Curahealth Hospital Heritage Valley UPMC Bedford Memorial Venango Heritage Valley Health System – Blair UPMC Northwest Heritage Valley Beaver UPMC Altoona Warren Berks Butler Warren General Hospital Penn State Health St. Joseph UPMC Passavant – Cranberry Reading Hospital Westmoreland Surgical Institute of Reading Cambria -

Save with Keystone HMO Proactive

Save with Keystone HMO Proactive Keystone HMO Proactive health plans use a tiered network, so you save on monthly premiums. Plus, you have the option to save even more on your out-of-pocket costs each time you receive covered services. How you’ll save Tier 1 – Preferred Like a typical HMO, you select a primary care physician who can refer you to specialists. You can visit any doctor or hospital in the Keystone Health Plan East network. We grouped our network into three tiers based on cost and, in many cases, quality measures. While all of the doctors and hospitals in our network must meet high quality standards, many offer services at a lower cost. You’ll pay the lowest out-of-pocket costs when you visit doctors Tier 2 – Enhanced Tier 3 – Standard and hospitals in Tier 1 – Preferred, which includes more than 50 percent of doctors and hospitals in the Keystone Health Plan East network. But the choice is always yours, and you can choose Tier 1 – Preferred for some services, and Tiers 2 or 3 for others. Also keep in mind: 50% of doctors and hospitals are • For some services, your out-of-pocket costs are the same in Tier 1 – Preferred. no matter what doctor or hospital you use, including preventive care, emergency room visits, and urgent care. Visit ibx.com/providerfinder, and select • For some services, like surgery, you pay out-of-pocket Keystone HMO Proactive under Your costs for both the facility and the performing doctor. To save the most money, you’ll want to make sure both Plan to find Tier 1 providers and save.