Prairie Falcon Prey in the Mojave Desert, California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

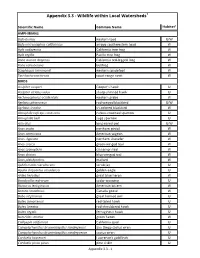

Appendix 3.3 - Wildlife Within Local Watersheds1

Appendix 3.3 - Wildlife within Local Watersheds1 2 Scientific Name Common Name Habitat AMPHIBIANS Bufo boreas western toad U/W Bufo microscaphus californicus arroyo southwestern toad W Hyla cadaverina California tree frog W Hyla regilla Pacific tree frog W Rana aurora draytonii California red-legged frog W Rana catesbeiana bullfrog W Scaphiopus hammondi western spadefoot W Taricha torosa torosa coast range newt W BIRDS Accipiter cooperi Cooper's hawk U Accipiter striatus velox sharp-shinned hawk U Aechmorphorus occidentalis western grebe W Agelaius phoeniceus red-winged blackbird U/W Agelaius tricolor tri-colored blackbird W Aimophila ruficeps canescens rufous-crowned sparrow U Aimophilia belli sage sparrow U Aiso otus long-eared owl U/W Anas acuta northern pintail W Anas americana American wigeon W Anas clypeata northern shoveler W Anas crecca green-winged teal W Anas cyanoptera cinnamon teal W Anas discors blue-winged teal W Anas platrhynchos mallard W Aphelocoma coerulescens scrub jay U Aquila chrysaetos canadensis golden eagle U Ardea herodius great blue heron W Bombycilla cedrorum cedar waxwing U Botaurus lentiginosus American bittern W Branta canadensis Canada goose W Bubo virginianus great horned owl U Buteo jamaicensis red-tailed hawk U Buteo lineatus red-shouldered hawk U Buteo regalis ferruginous hawk U Butorides striatus green heron W Callipepla californica California quail U Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus sandiegensis San Diego cactus wren U Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus sandiegoense cactus wren U Carduelis lawrencei Lawrence's -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Why Birds Are So Named

27 WHY BIRDS ARE SO NAMED. BY KATIE M. ROADS. “What’s in a name ?” Would some of the names of our birds suit one as well as another, or, as in other branches of science, has there been some significance attached to them or so1n.echaracteristic described by them ? While some birds rest content with one name, some have such marked pecularities as to attract the attention of different per- sons and each person has given his own interpretatioa of these by giving a name of his own. This may account for the 124 different names for thbeFlicker as complcid by Prank L. Burns. in The Wilson Bulletin No. 31. While all birds have not this motley array of names, the majority are supplied with several. In the following incomplete list it will be observed that the names employed involve practically every part of the bird’s external anatomy. The color involves the main color of the bird,as well as the colo’r of the head, the back, the wings, the tail, the under parts, the sides, the biK,and even peculiarities in markings. The shape and length of tail and bill, peculiarities of feet and Iegs, the pIace it frequents, the call notes, the song, the imitation in either form, color, or notes, and other things, including persons and places. While many of these names are more or I’ess useful in describing the bird, some of them are distinctly misleading or misnomers. It will be impossible to collate all names which every bird may be or may have been called by, therefore it seems wise to limit this paper to the vernacular or English names in gene.r- al use and of recognized standing in ornithological literature. -

!["Streaked Horned Lark Habitat Characteristics" [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0957/streaked-horned-lark-habitat-characteristics-pdf-480957.webp)

"Streaked Horned Lark Habitat Characteristics" [Pdf]

Photo: Rod Gilbert Streaked Horned Lark Habitat Characteristics Prepared by, Hannah E. Anderson Scott F. Pearson Center for Natural Lands Management Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife April 2015 Purpose Statement In this document, we attempt to identify landscape, site, and patch habitat features used by breeding streaked horned larks (Eremophila alpestris strigata). We provide this information in a hierarchical framework from weakest to strongest evidence of suitable habitat to help inform where to focus potential survey effort. We relied primarily on quantitative assessments to describe lark habitat but also use descriptions of occupied habitats and expert opinion where necessary. When using this document, it is important to consider that we had little to no information on the relative influence of different habitat conditions on lark reproduction and survival. In addition, larks readily use landscapes recently modified by humans (e.g., airfields, expanses of dredged material, agricultural fields), which indicates that the landscapes used by larks today are not necessarily reflective of those used in the past. Thus, we don’t discuss the fitness consequences of habitat selection to larks. Finally, because larks tend to use early successional habitats and vegetation conditions may change rapidly within and between seasons, habitat suitability may change over time depending on the site, the type of vegetation, and the nature of past and ongoing human disturbance. Because of these changing conditions, it may be necessary to periodically re- evaluate a site’s suitability. Our descriptions of landscape, site, and patch characteristics do not include information on the habitat used by larks historically or in portions of its range that are no longer occupied. -

Conference Highlights, Bird List and Photos

Highlights of the 2013 WFO Conference in Petaluma, California WFO’s 2013 Conference was one of our most successful meetings ever. We set a new WFO record with over 270 registrants. Science Sessions included descriptions of a new species of seabird, Bryan's Shearwater. Ed Harper’s photo ID quizzes tested our skills with visual challenges and Nathan Pieplow enlightened us with his creative and educational arrangements of bird sounds. The headquarters of PRBO Conservation Science gave us the ideal venue for our opening reception where we enjoyed seeing some of the latest work of artists Sophie Webb and Keith Hansen. We offered six workshops covering a variety of field skills. Thirty-eight field trips, including four pelagic trips, produced a list 240 species. Details below… WFO 2013 Petaluma Science Sessions The Science Sessions kicked off with Peter Pyle presenting on the discovery and identification of a new seabird species, Bryan's Shearwater. Thanks to the efforts of Debbie Vandooremolen and Dave Quady, the session offered a wide variety of presentations including papers on west coast occurrence and identification of "Vega" gull and Common Eider, numerous papers on status and conservation issues involving shorebirds, raptors, Black-backed Woodpecker, Gray Vireo, Tricolored Blackbird, Black Rail, Bendire's Thrasher, grassland birds of the southwest, and more. Other presentations covered use of "citizen science" data including eBird data and Breeding Bird Atlas results. Russ Bradley's Keynote talk gave us all a good overview of the great work being conducted by PRBO Conservation Science on the Farallon Islands and revealed some fascinating data about changes in the ocean ecosystem affecting breeding seabirds. -

MGS Survey Results Butte Valley

Mohave Ground Squirrel Trapping Results for Butte Valley Wildflower Sanctuary, Los Angeles County, California Prepared Under Permit Number 000972 for: County of Los Angeles Department of Parks and Recreations 1750 North Altadena Drive, Pasadena, California 91107 PH: (626) 398-5420 Cell: (626) 633-6948 Email: [email protected] Contact: Kim Bosell, Natural Areas Administrator Prepared by: Edward L. LaRue, Jr. (Permanent ID Number SC-001544) Circle Mountain Biological Consultants, Inc. P.O. Box 3197 Wrightwood, California 92397 PH: (760) 249-4948 FAX: (760) 249-4948 Email: [email protected] Circle Mountain Biological Consultants, Inc. Author and Field Investigator: Edward L. LaRue, Jr. July 2014 Mohave Ground Squirrel Trapping Results for Butte Valley Wildflower Sanctuary, Los Angeles County, California 1.0. INTRODUCTION 1.1. Purpose and Need for Study. Herein, Edward L. LaRue, Jr., the Principal Investigator under a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) (expires 4/30/2016), Scientific Collecting Permit Number SC-001544, reports results of trapping surveys to assess the presence of the state-listed, Threatened Mohave ground squirrel (MGS) (Xerospermophilus mohavensis) on the subject property. This study, which was completed on the Butte Valley Wildflower Sanctuary (herein “Butte Valley” or “Sanctuary”) in northeastern Los Angeles County (Figures 1 through 3), California is authorized under Permit Number 000972. In recent decades, there have been very few MGS records in the desert region of northeastern Los Angeles County. In spite of protocol trapping efforts since 1998, the only confirmed MGS captures in Los Angeles County have been at several locations in a small area on Edwards Air Force Base (Leitner 2008). -

Life History Variation Between High and Low Elevation Subspecies of Horned Larks Eremophila Spp

J. Avian Biol. 41: 273Á281, 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-048X.2009.04816.x # 2010 The Authors. J. Compilation # 2010 J. Avian Biol. Received 29 January 2009, accepted 10 August 2009 Life history variation between high and low elevation subspecies of horned larks Eremophila spp. Alaine F. Camfield, Scott F. Pearson and Kathy Martin A. F. Camfield ([email protected]) and K. Martin, Centr. for Appl. Conserv. Res., Fac. of Forestry, Univ. of British Columbia, 2424 Main Mall, Vancouver, B.C., Canada, V6T 1Z4. AFC and KM also at: Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, 351 St. Joseph Blvd., Gatineau, QC K1A 0H3. Á S. F. Pearson, Wildl. Sci. Div., Washington Dept. of Fish and Wildl., 1111 Washington St. SE, Olympia, WA, USA, 98501-1091. Environmental variation along elevational gradients can strongly influence life history strategies in vertebrates. We investigated variation in life history patterns between a horned lark subspecies nesting in high elevation alpine habitat Eremophila alpestris articola and a second subspecies in lower elevation grassland and sandy shoreline habitats E. a. strigata. Given the shorter breeding season and colder climate at the northern alpine site we expected E. a. articola to be larger, have lower fecundity and higher apparent survival than E. a. strigata. As predicted, E. a. articola was larger and the trend was toward higher apparent adult survival for E. a. articola than E. a. strigata (0.69 vs 0.51). Contrary to our predictions, however, there was a trend toward higher fecundity for E. a. articola (1.75 female fledglings/female/year vs 0.91). -

Workshop Proceedings

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. ALPINE BIRD COMMUNITIES OF WESTERN NORTH AMERICA: IMPLICATIONS FOR MANAGEMENT AND RESEARcH!/ Clait E. Braun Wildlife Researcher Colorado Division of Wildlife, Research Center, 317 West Prospect Street, Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 ABSTRACT The avifauna of alpine regions of western North America is notably depauperate. Average community size is normally 3 to 4 although 5 species may consistently breed and nest above treeline. Only 1 species is a year around resident and totally dependent upon alpine habitats. Seasonal habitat preferences of the breeding avifauna are identified and the complexity of the processes and factors influencing alpine regions are reviewed. Management problems are discussed and research opportunities are identified. KEYWORDS: alpine ecosystem, habitat, avifauna, management, western North America. INTRODUCTION Alpine ecosystems occur in most of the high mountain cordilleras of western North America. Alpine, as used in this paper, refers to the area above treeline where habitats are characterized by short growing seasons, low temperatures and high winds. The term "tundra" is frequently used to describe these habitats but is more properly used in connection with arctic areas north of the limit of forest growth (Hoffmann and Taber 1967). While use of the terms "alpine tundra" and "arctic tundra" is common in designating above treeline (alpine) and northern lowland areas (arctic), the terminology of Billings (1979) is preferred. Likewise, lumping of alpine and arctic ecosystems into the "tundra biome" (see Kendeigh 1961) is not really feasible because of the extreme differences in radiation, moisture, topography, photo period, presence or absence of permafrost, etc. -

Pre-Lesson Plan

Pre-Lesson Plan Prior to taking part in the Winged Migration program at Tommy Thompson Park it is recommended that you complete the following lessons to familiarize your students with some of the birds they might see and some of the concepts they will learn during their field trip. The lessons can easily be integrated into your Science, Language Arts, Social Studies and Physical Education programs. Part 1: Amazing Birds As a class, read the provided “Wanted” posters. The posters depict a very small sampling of some of the amazing feats and features of birds. To complement these readings, display the following websites so that students can see some of these birds “up close.” Common Loon http://www.schollphoto.com/gallery/thumbnails.php?album=1 Black-Capped Chickadee http://sdakotabirds.com/species_photos/black_capped_chickadee.htm Ruby-Throated Hummingbird http://www.surfbirds.com/cgi-bin/gallery/search2.cgi?species=Ruby- throated%20Hummingbird Downy Woodpecker http://www.pbase.com/billko/downy_woodpecker Great Horned Owl www.owling.com/Great_Horned.htm When you visit Tommy Thompson Park, you may see chickadees, hummingbirds, and woodpeckers. These birds all breed in southern Ontario. However, you probably will not see a Great Horned Owl, because this specific bird is usually flying around at night. Below is a list of some other birds students might see when they visit Tommy Thompson Park. Have them chose one bird each and write a “Wanted” poster for it, focusing on a cool fact about that bird. Some web sites that will help them get started -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and -

Plant Life Zones

Plant Life Zones 11,500’ + 9,200 – 11,500’ 8,500 – 9,200’ 7,500 – 8,500’ 5,000 – 7,500’ 3,800 – 5,000’ ArcticAlpine Life Zone: Also termed the Alpine Tundra Zone, it is above 11,500 feet and may receive over 33 inches of precipitation per year. This zone occurs above treeline. Plant life in this zone includes herbs, grasses, sedges, rushes, mosses and lichens. Subalpine fir, bristlecone pine, limber pine and Engelmann spruce are the only trees that survive in this zone, usually in bizarre, gnarled forms. Hudsonian Life Zone: Also called the Spruce-Fir Zone because the dominant plant species are Engelmann spruce, blue spruce, bristlecone pine, corkbark fir and shrubby cinquefoil. The elevation range for this life zone is between 9,200 feet and 11,500 feet. Annual precipitation for this zone is 26 inches or more. The redbreasted nuthatch, olivesided flycatcher, blue grouse and red crossbill are birds that can be seen in this zone. Mammals include marmot, pocket gopher, porcupine, and big horn sheep. Canadian Life Zone: Because this zone includes a mixture of conifer trees it is also called the Mixed Conifer Zone. It is usually in the mountainous areas of the state and includes dense, shady forests. The dominant plant species in this zone are Douglas-fir, white fir, ponderosa pine, aspen, water birch, Rocky Mountain juniper, southwestern white pine, and narrowleaf cottonwood. Annual precipitation is between 20 and 26 inches and the elevation is at or above 8,500 feet and at or below 9,200 feet. -

!["Streaked Horned Lark Brochure on Nesting Habitat" [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2204/streaked-horned-lark-brochure-on-nesting-habitat-pdf-2002204.webp)

"Streaked Horned Lark Brochure on Nesting Habitat" [Pdf]

Areas less than 100yd from trees, treelines, or other tall structures are not suitable nesting habitat. Mudflats and other drowned out areas can provide nesting sites in the springtime when these areas are dried out, leaving open areas with sparse Gravel road shoulders and vegetation. field margins with low, sparse vegetation provide likely lark nesting sites. Open fencerows The Streaked Horned Lark with low, sparse nests on the ground in areas vegetation are with low, sparse vegetation ideal for lark within open landscapes of nesting habitat, 300 acres or more. unlike fencerows with trees or bushes. Meet the Streaked WHAT KIND OF HABITAT DOES THE working to develop funds and the federal Endangered Species Act horned lark STREAKED HORNED LARK PREFER? voluntary incentive programs to help (ESA). Under the threatened listing, a land managers, including farmers, special rule exempts farmers from ESA The Streaked The Streaked Horned Lark nests on enhance nesting habitat for the violations when performing agricultural Horned Lark is the ground in sites with low, sparse Steaked Horned Lark. operations in areas where the lark a small ground- vegetation. Historically, this type is found. However, the continued loss Potential management opportunities dwelling bird with a brown back, a of habitat was found in prairies in of breeding habitat is pushing this for farmers include: black mask, and yellow and white western Oregon and Washington, bird closer to extinction. The Lark markings on its head, plus a couple usually after disturbances such Management of field borders and Partnership is seeking opportunities small feathers or ‘horns’ which earn it as flooding or fire.