Life History Variation Between High and Low Elevation Subspecies of Horned Larks Eremophila Spp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When and How to Study the Nesting Biology of Indian Birds: Research Needs, Ethical Considerations, and Best Practices

BARVE ET AL.: Nesting biology of Indian birds 1 When and how to study the nesting biology of Indian birds: Research needs, ethical considerations, and best practices Sahas Barve, T. R. Shankar Raman, Aparajita Datta & Girish Jathar Barve, S., Raman, T. R. S, Datta, A., & Jathar, G., 2020. When and how to study the nesting biology of Indian birds: Research needs, ethical considerations, and best practices. Indian BIRDS 16 (1): 1–9. Sahas Barve, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, 10th Street and Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, D.C. 20560. E-mail: [email protected]. [Corresponding author.] T. R. Shankar Raman, Nature Conservation Foundation, 1311, ‘Amritha’, 12th A Main, Vijayanagar 1st Stage, Mysore 570017, Karnataka, India. Aparajita Datta, Nature Conservation Foundation, 1311, ‘Amritha’, 12th A Main, Vijayanagar 1st Stage, Mysore 570017, Karnataka, India. Girish Jathar, Bombay Natural History Society, Hornbill House, Dr Salim Ali Chowk, Shaheed Bhagat Singh Road, Mumbai 400001, Maharashtra, India. Manuscript received on 03 February 2020. Abstract The nesting biology of a bird species is likely the most important component of its life history and it is affected by several ecological and environmental factors. Various components of avian nesting biology have proved to be important traits for testing fundamental ecological and evolutionary hypotheses, and for monitoring the efficacy of biological conservation programs. Despite its significance, the nesting biology of most Indian bird species is still poorly understood. The past few years have, however, seen a significant increase in the number of submissions to Indian BIRDS, of observational studies of avian nesting biology, which promises an exciting new wave of ornithological natural history research in India. -

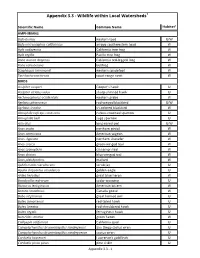

Appendix 3.3 - Wildlife Within Local Watersheds1

Appendix 3.3 - Wildlife within Local Watersheds1 2 Scientific Name Common Name Habitat AMPHIBIANS Bufo boreas western toad U/W Bufo microscaphus californicus arroyo southwestern toad W Hyla cadaverina California tree frog W Hyla regilla Pacific tree frog W Rana aurora draytonii California red-legged frog W Rana catesbeiana bullfrog W Scaphiopus hammondi western spadefoot W Taricha torosa torosa coast range newt W BIRDS Accipiter cooperi Cooper's hawk U Accipiter striatus velox sharp-shinned hawk U Aechmorphorus occidentalis western grebe W Agelaius phoeniceus red-winged blackbird U/W Agelaius tricolor tri-colored blackbird W Aimophila ruficeps canescens rufous-crowned sparrow U Aimophilia belli sage sparrow U Aiso otus long-eared owl U/W Anas acuta northern pintail W Anas americana American wigeon W Anas clypeata northern shoveler W Anas crecca green-winged teal W Anas cyanoptera cinnamon teal W Anas discors blue-winged teal W Anas platrhynchos mallard W Aphelocoma coerulescens scrub jay U Aquila chrysaetos canadensis golden eagle U Ardea herodius great blue heron W Bombycilla cedrorum cedar waxwing U Botaurus lentiginosus American bittern W Branta canadensis Canada goose W Bubo virginianus great horned owl U Buteo jamaicensis red-tailed hawk U Buteo lineatus red-shouldered hawk U Buteo regalis ferruginous hawk U Butorides striatus green heron W Callipepla californica California quail U Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus sandiegensis San Diego cactus wren U Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus sandiegoense cactus wren U Carduelis lawrencei Lawrence's -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Why Birds Are So Named

27 WHY BIRDS ARE SO NAMED. BY KATIE M. ROADS. “What’s in a name ?” Would some of the names of our birds suit one as well as another, or, as in other branches of science, has there been some significance attached to them or so1n.echaracteristic described by them ? While some birds rest content with one name, some have such marked pecularities as to attract the attention of different per- sons and each person has given his own interpretatioa of these by giving a name of his own. This may account for the 124 different names for thbeFlicker as complcid by Prank L. Burns. in The Wilson Bulletin No. 31. While all birds have not this motley array of names, the majority are supplied with several. In the following incomplete list it will be observed that the names employed involve practically every part of the bird’s external anatomy. The color involves the main color of the bird,as well as the colo’r of the head, the back, the wings, the tail, the under parts, the sides, the biK,and even peculiarities in markings. The shape and length of tail and bill, peculiarities of feet and Iegs, the pIace it frequents, the call notes, the song, the imitation in either form, color, or notes, and other things, including persons and places. While many of these names are more or I’ess useful in describing the bird, some of them are distinctly misleading or misnomers. It will be impossible to collate all names which every bird may be or may have been called by, therefore it seems wise to limit this paper to the vernacular or English names in gene.r- al use and of recognized standing in ornithological literature. -

!["Streaked Horned Lark Habitat Characteristics" [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0957/streaked-horned-lark-habitat-characteristics-pdf-480957.webp)

"Streaked Horned Lark Habitat Characteristics" [Pdf]

Photo: Rod Gilbert Streaked Horned Lark Habitat Characteristics Prepared by, Hannah E. Anderson Scott F. Pearson Center for Natural Lands Management Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife April 2015 Purpose Statement In this document, we attempt to identify landscape, site, and patch habitat features used by breeding streaked horned larks (Eremophila alpestris strigata). We provide this information in a hierarchical framework from weakest to strongest evidence of suitable habitat to help inform where to focus potential survey effort. We relied primarily on quantitative assessments to describe lark habitat but also use descriptions of occupied habitats and expert opinion where necessary. When using this document, it is important to consider that we had little to no information on the relative influence of different habitat conditions on lark reproduction and survival. In addition, larks readily use landscapes recently modified by humans (e.g., airfields, expanses of dredged material, agricultural fields), which indicates that the landscapes used by larks today are not necessarily reflective of those used in the past. Thus, we don’t discuss the fitness consequences of habitat selection to larks. Finally, because larks tend to use early successional habitats and vegetation conditions may change rapidly within and between seasons, habitat suitability may change over time depending on the site, the type of vegetation, and the nature of past and ongoing human disturbance. Because of these changing conditions, it may be necessary to periodically re- evaluate a site’s suitability. Our descriptions of landscape, site, and patch characteristics do not include information on the habitat used by larks historically or in portions of its range that are no longer occupied. -

Conference Highlights, Bird List and Photos

Highlights of the 2013 WFO Conference in Petaluma, California WFO’s 2013 Conference was one of our most successful meetings ever. We set a new WFO record with over 270 registrants. Science Sessions included descriptions of a new species of seabird, Bryan's Shearwater. Ed Harper’s photo ID quizzes tested our skills with visual challenges and Nathan Pieplow enlightened us with his creative and educational arrangements of bird sounds. The headquarters of PRBO Conservation Science gave us the ideal venue for our opening reception where we enjoyed seeing some of the latest work of artists Sophie Webb and Keith Hansen. We offered six workshops covering a variety of field skills. Thirty-eight field trips, including four pelagic trips, produced a list 240 species. Details below… WFO 2013 Petaluma Science Sessions The Science Sessions kicked off with Peter Pyle presenting on the discovery and identification of a new seabird species, Bryan's Shearwater. Thanks to the efforts of Debbie Vandooremolen and Dave Quady, the session offered a wide variety of presentations including papers on west coast occurrence and identification of "Vega" gull and Common Eider, numerous papers on status and conservation issues involving shorebirds, raptors, Black-backed Woodpecker, Gray Vireo, Tricolored Blackbird, Black Rail, Bendire's Thrasher, grassland birds of the southwest, and more. Other presentations covered use of "citizen science" data including eBird data and Breeding Bird Atlas results. Russ Bradley's Keynote talk gave us all a good overview of the great work being conducted by PRBO Conservation Science on the Farallon Islands and revealed some fascinating data about changes in the ocean ecosystem affecting breeding seabirds. -

MGS Survey Results Butte Valley

Mohave Ground Squirrel Trapping Results for Butte Valley Wildflower Sanctuary, Los Angeles County, California Prepared Under Permit Number 000972 for: County of Los Angeles Department of Parks and Recreations 1750 North Altadena Drive, Pasadena, California 91107 PH: (626) 398-5420 Cell: (626) 633-6948 Email: [email protected] Contact: Kim Bosell, Natural Areas Administrator Prepared by: Edward L. LaRue, Jr. (Permanent ID Number SC-001544) Circle Mountain Biological Consultants, Inc. P.O. Box 3197 Wrightwood, California 92397 PH: (760) 249-4948 FAX: (760) 249-4948 Email: [email protected] Circle Mountain Biological Consultants, Inc. Author and Field Investigator: Edward L. LaRue, Jr. July 2014 Mohave Ground Squirrel Trapping Results for Butte Valley Wildflower Sanctuary, Los Angeles County, California 1.0. INTRODUCTION 1.1. Purpose and Need for Study. Herein, Edward L. LaRue, Jr., the Principal Investigator under a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) (expires 4/30/2016), Scientific Collecting Permit Number SC-001544, reports results of trapping surveys to assess the presence of the state-listed, Threatened Mohave ground squirrel (MGS) (Xerospermophilus mohavensis) on the subject property. This study, which was completed on the Butte Valley Wildflower Sanctuary (herein “Butte Valley” or “Sanctuary”) in northeastern Los Angeles County (Figures 1 through 3), California is authorized under Permit Number 000972. In recent decades, there have been very few MGS records in the desert region of northeastern Los Angeles County. In spite of protocol trapping efforts since 1998, the only confirmed MGS captures in Los Angeles County have been at several locations in a small area on Edwards Air Force Base (Leitner 2008). -

(Sarracenia) Provide a 21St-Century Perspective on Infraspecific Ranks and Interspecific Hybrids: a Modest Proposal* for Appropriate Recognition and Usage

Systematic Botany (2014), 39(3) © Copyright 2014 by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists DOI 10.1600/036364414X681473 Date of publication 05/27/2014 Pitcher Plants (Sarracenia) Provide a 21st-Century Perspective on Infraspecific Ranks and Interspecific Hybrids: A Modest Proposal* for Appropriate Recognition and Usage Aaron M. Ellison,1,5 Charles C. Davis,2 Patrick J. Calie,3 and Robert F. C. Naczi4 1Harvard University, Harvard Forest, 324 North Main Street, Petersham, Massachusetts 01366, U. S. A. 2Harvard University Herbaria, Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, 22 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, U. S. A. 3Eastern Kentucky University, Department of Biological Sciences, 521 Lancaster Avenue, Richmond, Kentucky 40475, U. S. A. 4The New York Botanical Garden, 2900 Southern Boulevard, Bronx, New York 10458, U. S. A. 5Author for correspondence ([email protected]) Communicating Editor: Chuck Bell Abstract—The taxonomic use of infraspecific ranks (subspecies, variety, subvariety, form, and subform), and the formal recognition of interspecific hybrid taxa, is permitted by the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants. However, considerable confusion regarding the biological and systematic merits is caused by current practice in the use of infraspecific ranks, which obscures the meaningful variability on which natural selection operates, and by the formal recognition of those interspecific hybrids that lack the potential for inter-lineage gene flow. These issues also may have pragmatic and legal consequences, especially regarding the legal delimitation and management of threatened and endangered species. A detailed comparison of three contemporary floras highlights the degree to which infraspecific and interspecific variation are treated inconsistently. -

The Effect of Climate Change on the Correlation Between Avian Life-History Traits

Global Change Biology (2005) 11, 1606–1613, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.01038.x The effect of climate change on the correlation between avian life-history traits CHRISTIAAN BOTH1 andMARCEL E. VISSER Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW), PO Box 40, 6666 ZG Heteren, The Netherlands Abstract The ultimate reason why birds should advance their phenology in response to climate change is to match the shifting phenology of underlying levels of the food chain. In a seasonal environment, the timing of food abundance is one of the crucial factors to which birds should adapt their timing of reproduction. They can do this by shifting egg-laying date (LD), and also by changing other life-history characters that affect the period between laying of the eggs and hatching of the chicks. In a long-term study of the migratory Pied Flycatcher, we show that the peak of abundance of nestling food (caterpillars) has advanced during the last two decades, and that the birds advanced their LD. LD strongly correlates with the timing of the caterpillar peak, but in years with an early food peak the birds laid their eggs late relative to this food peak. In such years, the birds advance their hatching date by incubating earlier in the clutch and reducing the interval between laying the last egg to hatching of the first egg, thereby partly compensating for their relative late LD. Paradoxically, they also laid larger clutches in the years with an early food peak, and thereby took more time to lay (i.e. one egg per day). -

Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops Fuscatus)

Adaptations of An Avian Supertramp: Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops fuscatus) Chapter 6: Survival and Dispersal The pearly-eyed thrasher has a wide geographical distribution, obtains regional and local abundance, and undergoes morphological plasticity on islands, especially at different elevations. It readily adapts to diverse habitats in noncompetitive situations. Its status as an avian supertramp becomes even more evident when one considers its proficiency in dispersing to and colonizing small, often sparsely The pearly-eye is a inhabited islands and disturbed habitats. long-lived species, Although rare in nature, an additional attribute of a supertramp would be a even for a tropical protracted lifetime once colonists become established. The pearly-eye possesses passerine. such an attribute. It is a long-lived species, even for a tropical passerine. This chapter treats adult thrasher survival, longevity, short- and long-range natal dispersal of the young, including the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of natal dispersers, and a comparison of the field techniques used in monitoring the spatiotemporal aspects of dispersal, e.g., observations, biotelemetry, and banding. Rounding out the chapter are some of the inherent and ecological factors influencing immature thrashers’ survival and dispersal, e.g., preferred habitat, diet, season, ectoparasites, and the effects of two major hurricanes, which resulted in food shortages following both disturbances. Annual Survival Rates (Rain-Forest Population) In the early 1990s, the tenet that tropical birds survive much longer than their north temperate counterparts, many of which are migratory, came into question (Karr et al. 1990). Whether or not the dogma can survive, however, awaits further empirical evidence from additional studies. -

Terrapene Carolina (Linnaeus 1758) – Eastern Box Turtle, Common Box Turtle

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation Project ofEmydidae the IUCN/SSC — TortoiseTerrapene and Freshwatercarolina Turtle Specialist Group 085.1 A.G.J. Rhodin, P.C.H. Pritchard, P.P. van Dijk, R.A. Saumure, K.A. Buhlmann, J.B. Iverson, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.085.carolina.v1.2015 © 2015 by Chelonian Research Foundation • Published 26 January 2015 Terrapene carolina (Linnaeus 1758) – Eastern Box Turtle, Common Box Turtle A. ROSS KIESTER1 AND LISABETH L. WILLEY2 1Turtle Conservancy, 49 Bleecker St., Suite 601, New York, New York 10012 USA [[email protected]]; 2Department of Environmental Studies, Antioch University New England, 40 Avon St., Keene, New Hampshire 03431 USA [[email protected]] SUMMARY. – The Eastern Box Turtle, Terrapene carolina (Family Emydidae), as currently understood, contains six living subspecies of small turtles (carapace lengths to ca. 115–235 mm) able to close their hinged plastrons into a tightly closed box. Although the nominate subspecies is among the most widely distributed and well-known of the world’s turtles, the two Mexican subspecies are poorly known. This primarily terrestrial, though occasionally semi-terrestrial, species ranges throughout the eastern and southern United States and disjunctly in Mexico. It was generally recognized as common in the USA throughout the 20th century, but is now threatened by continuing habitat conversion, road mortality, and collection for the pet trade, and notable population declines have been documented throughout its range. In the United States, this turtle is a paradigm example of the conservation threats that beset and impact a historically common North American species. -

Phylum Arthropoda*

Zootaxa 3703 (1): 017–026 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Correspondence ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3703.1.6 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:FBDB78E3-21AB-46E6-BD4F-A4ADBB940DCC Phylum Arthropoda* ZHI-QIANG ZHANG New Zealand Arthropod Collection, Landcare Research, Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand; [email protected] * In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (Ed.) Animal Biodiversity: An Outline of Higher-level Classification and Survey of Taxonomic Richness (Addenda 2013). Zootaxa, 3703, 1–82. Abstract The Arthropoda is here estimated to have 1,302,809 described species, including 45,769 fossil species (the diversity of fossil taxa is here underestimated for many taxa of the Arthropoda). The Insecta (1,070,781 species) is the most successful group, and it alone accounts for over 80% of all arthropods. The most successful insect order, Coleoptera (392,415 species), represents over one-third of all species in 39 insect orders. Another major group in Arthropoda is the class Arachnida (114,275 species), which is dominated by the Acari (55,214 mite and tick species) and Araneae (44,863 spider species). Other diverse arthropod groups include Crustacea (73,141 species), Trilobitomorpha (20,906 species) and Myriapoda (12,010 species). Key words: Classification, diversity, Arthropoda Introduction The Arthropoda, with over 1.5 million described species, is the largest animal phylum, and it alone accounts for about 80% of the total number of species in the animal kingdom (Zhang 2011a). In the last volume on animal higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness, 28 chapters by numerous teams of specialists were published on various taxa of the Arthropoda, but there were many gaps to be filled (Zhang 2011b).