Specific Performance, Expectation Damages and Hybrid Mechanisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expectation, Reliance, and the Two Contractual Wrongs

Expectation, Reliance, and the Two Contractual Wrongs CHRISTOPHER T. WONNELL* TABLE OF CONTENTS L INTRODUCTION: THE PLACE OF EXPECTATION AND RELIANCE IN CONTRACTUAL DECISION MAKING ............................................. 54 A. Two ContractualDecisions in Need of Moral Assessment ................54 B. Six Motivesfor Making and Then Breaking a Particular Contract................................................................................................. 60 1. Taking Advantage of NonsimultaneousPerformances ................... 60 2. Making a Threat to Breach in the Face of Situational Monopoly Credible....................................................................... 62 3. Refusing to Carry Through on an Agreed-upon Allocation of Risk ......................................................................... 63 4. Seeking to AppropriateInformation Productively Brought to Bearon the Transactionby the Promisee..................... 66 5. Seeking to Avoid the Contract Because of a Mistake That Makes the ContractMore Burdensome to the PromisorThan Anticipated and Correspondingly More Profitableto the Promisee.................................................. 72 6. Seeking to Avoid the Contract Because of a Mistake That Makes the ContractMore Burdensome to the PromisorThan Anticipated Without Becoming CorrespondinglyMore Profitableto the Promisee........................ 75 * Professor of Law, University of San Diego School of Law. J.D. 1982, University of Michigan; B.A. 1979, Northwestern University. This Article was selected by -

1. the Issue Is Whether the Trial Court Erred in Awarding the Rancher, An

STUDENT ANSWER 1: 1. The issue is whether the trial court erred in awarding the Rancher, an aggrieved party in a breach of contract claim, a $500,000 award for restoration of the Ranch when the breaching party showed by expert testimony a diminution of value of only $20,000 in the Ranch’s current condition? The trial court had already determined that an enforceable contract existed between the Rancher and Gasco, and that the contract was breached by Gasco when it failed to restore the Ranch to its pre-exploration condition by March 31. The sole issue here is the issue of damages. Specifically, whether the award of $500,000 to restore the ranch was grossly and unfairly out of proportion to the benefit to be achieved? Remedies for breach of contract seek to compensate an aggrieved party for profits that were prevented and losses sustained due to the breach of contract. Typically, three (3) types of damages are available to an aggrieved party under Common Law contract law (UCC Article 2 does not apply here since the contract does not involve the sale of good but rather a lease for real property): (1) restitution damages, (2) reliance damages, and (3) expectation damages. The first two types of damages help an aggrieved party recover the benefit bestowed upon a breaching party to prevent its unjust enrichment, which includes the recovery of out-of-pocket expenses, if foreseeable and ascertainable at the time of the breach, that were wasted by the aggrieved party in getting ready to perform. The third type of damages, expectation damages, aims to place an aggrieved party in the same financial position as if the contract had been fully performed and not breached. -

Why Expectation Damages for Breach of Contract Must Be the Norm: a Refutation of the Fuller and Perdue "Three Interests&Quo

Nebraska Law Review Volume 81 | Issue 3 Article 2 2003 Why Expectation Damages for Breach of Contract Must Be the Norm: A Refutation of the Fuller and Perdue "Three Interests" Thesis W. David Slawson University of Southern California Gould School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation W. David Slawson, Why Expectation Damages for Breach of Contract Must Be the Norm: A Refutation of the Fuller and Perdue "Three Interests" Thesis, 81 Neb. L. Rev. (2002) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol81/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. W. David Slawson* Why Expectation Damages for Breach of Contract Must Be the Norm: A Refutation of the Fuller and Perdue "Three Interests" Thesis TABLE OF CONTENTS 840 I. Introduction .......................................... Principal Institutions in a Modern Market II. The 843 Economy in Which Contracts Are Used ................ A. The Institution of the Economic Market: Contracts 843 as Bargains ....................................... Institution of Credit and Finance: Contracts as B. The 845 Property .......................................... 846 the Institutions' Needs ....................... III. Meeting 846 A. Providing a Remedy for Every Breach ............. Contracts Enforceable as Soon as They Are B. Making 847 M ade ............................................. Has Compensating the Injured Party for What He C. 848 ost ............................................... L 848 Damages Under the Expectation Measure ...... 1. 849 2. Damages Under the Reliance Measure ......... 849 a. -

Practice Hypotheticals Contracts

Practice Hypotheticals Contracts Evaluation Sheet: “Amy and the Convertible” 1. Threshold question: Was there a contract? Need to identify the overriding question of whether enforceable promises were made. Here there was an exchange of promise to wash and wax a car for ten weeks and a promise to pay $600. 2. If so, what kind of contract? Is it a contract for the sale of goods or services? Need to identify the nature of the parties’ agreement to determine the rule of law to apply: whether the UCC or common law. Since the nature of the agreement is one for personal services (washing the car) and not a transaction in goods, the common law is applicable 3. What are Ben’s damages? General rule: Every breach of contract entitles the aggrieved party to sue for damages. The general theory of damages in contract actions is that the injured party should be placed in the same position as if the contract had been properly performed, at least so far as money can do this. Compensatory damages are designed to give the plaintiff the benefit of his bargain. Expectation damages Rule: This interest represents the “benefit of the bargain” and would include all that Ben expected to earn over the course of the contract. It is what the injured party had expected to receive under the contract “but for” the breach, less expenses saved by not having to perform. Application: Here, Ben would have earned $600 over the life of the contract, the amount she promised to pay him. He said he needed to spend $50 for supplies, so $550 was pure profit. -

The Purpose of Compensatory Damages in Tort and Fraudulent Misrepresentation

LENS FINAL 12/1/2010 5:47:02 PM Honest Confusion: The Purpose of Compensatory Damages in Tort and Fraudulent Misrepresentation Jill Wieber Lens∗ I. INTRODUCTION Suppose that a plaintiff is injured in a rear-end collision car accident. Even though the rear-end collision was not a dramatic accident, the plaintiff incurred extensive medical expenses because of a preexisting medical condition. Through a negligence claim, the plaintiff can recover compensatory damages based on his medical expenses. But is it fair that the defendant should be liable for all of the damages? It is not as if he rear-ended the plaintiff on purpose. Maybe the fact that defendant’s conduct was not reprehensible should reduce the amount of damages that the plaintiff recovers. Any first-year torts student knows that the defendant’s argument will not succeed. The defendant’s conduct does not control the amount of the plaintiff’s compensatory damages. The damages are based on the plaintiff’s injury because, in tort law, the purpose of compensatory damages is to make the plaintiff whole by putting him in the same position as if the tort had not occurred.1 But there are tort claims where the amount of compensatory damages is not always based on the plaintiff’s injury. Suppose that a defendant fraudulently misrepresents that a car for sale is brand-new. The plaintiff then offers to purchase the car for $10,000. Had the car actually been new, it would have been worth $15,000, but the car was instead worth only $10,000. As they have for a very long time, the majority of jurisdictions would award the plaintiff $5000 in compensatory damages 2 based on the plaintiff’s expected benefit of the bargain. -

Chapter 9 Topics in the Economics of Contract Law I. Remedies As

Chapter 9 Topics in the Economics of Contract Law I. Remedies as incentives A. Alternative remedies Different remedies create different incentives for the parties to a contract. Our focus is how different remedies affect the incentives each party has to act in an economically efficient manner. 1. Expectation damages Perfect expectation damages (PED) are meant to leave the promisee indifferent between performance and nonperformance of the contract. The baseline is value to promisee if contract was performed. Damages then are equal to the difference between the net value of performance of the contract and no contract . 2. Reliance damages In this case, the injury that is caused by breach focuses on the costs the promisee has incurred as a result of relying on the contract. As such, perfect reliance damages (PRD) are meant to leave the promisee indifferent between no contract and breach of the contract. The baseline is no contract. Damages then are equal to the promisee’s net reliance costs. 3. Opportunity cost damages In this case, the injury that is caused by breach focuses on the costs the promisee has incurred as a result of foregoing alternative contracts. As such, perfect opportunity cost damages (POCD) are meant to leave the promisee indifferent between breach of the contract and performance of the next best contract. The baseline is value to promisee of the next best contract. Damages then are equal to difference between the net value of performance of the next best contract and no contract. 4. The typical relationship between PED, POCD and PRD and the problem of subjective value a. -

The Phantom Reliance Interest in Tort Damages

The Phantom Reliance interest in Tort Damages MICHAEL B. KELLY* TABLE OF CONTENTS L INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 169 IL THE RELIANCE INTEREST IN MISREPRESENTATION .............................................. 171 III. RELIANCE IN PERSONAL INJURY CASES ............................................................... 176 IV. WHAT DOES IT ALL MEAN? ....................................... ... .... .... .... .... ... ..... ... .... .... .. 189 I. INTRODUCTION The reliance interest has fascinated me for some time.' As a measure of damages for breach of contract,2 it seems theoretically unjustified and flawed in its implementation. In theory, it requires compensation for lost opportunities? In practice, such compensation is rarely provided'- * Professor of Law, University of San Diego School of Law. J.D. 1983, B.G.S. 1975, University of Michigan; M.A. 1980, University of Illinois. 1. Michael B. Kelly, The Phanton Reliance Interest in Contract Damages, 1992 WIS. L. REv. 1755. 2. My focus has been on contracts, full-fledged bargains, rather than promissory estoppel or other instances where the reliance interest might be applied. Much of my criticism of the reliance interest has been limited to this context. This Article will expand somewhat the scope of my criticism. 3. L.L. Fuller & William R. Perdue, Jr., The Reliance Interest in Contract Damages: 1, 46 YALE LJ. 52, 55, 60-61 (1936); Mark Pettit, Jr., PrivateAdvantage and Public Power: Reexamining the Expectation and Reliance Interests in Contract Damages, 38 HASTINGS L.J 417,420-21 (1987). unless one counts the expectation interest as a proxy for opportunities lost in reliance on a promise.5 In theory, it justifies recoveries that may exceed expectation.6 Yet, even its progenitors refused to endorse that implication.7 Why, then, does the reliance interest have continuing appeal? One explanation has emerged from discussions with academics: the reliance interest seems apt to some because it resembles tort remedies. -

In Defense of the Impossibility Defense Gerhard Wagner Georg-August University of Goettingen

Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 27 Article 4 Issue 1 Fall 1995 1995 In Defense of the Impossibility Defense Gerhard Wagner Georg-August University of Goettingen Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Contracts Commons Recommended Citation Gerhard Wagner, In Defense of the Impossibility Defense, 27 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 55 (1995). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol27/iss1/4 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Essay In Defense of the Impossibility Defense GerhardWagner* I. INTRODUCTION Generally, the common law follows the rule of pacta sunt servanda' under which contractual obligations are absolutely binding on the parties. 2 The impossibility defense is an exception to this general rule.3 Under the impossibility defense, a promisor may default with- out incurring liability for the promisee's expectation damages.4 * Akademischer Rat (Junior Lecturer) at Georg-August University of Goettingen, Germany; J.D., 1989, University of Goettingen; L.L.M., 1995, University of Chicago. The author is deeply indebted to Richard Craswell of the University of Chicago Law School for many helpful comments on an earlier draft of this Essay. 1. "Pacta sunt servanda" means "agreements (and stipulations) of the parties (to a contract) must be observed." BLACK'S LAW DICTIONARY 1109 (6th ed. 1990). 2. For an erudite discussion of pacta sunt servanda, see generally Richard Hyland, Pacta Sunt Servanda: A Meditation, 34 VA. -

Reexamining the Expectation and Reliance Interests in Contract Damages Mark Pettit Jr

Hastings Law Journal Volume 38 | Issue 3 Article 2 1-1987 Private Advantage and Public Power: Reexamining the Expectation and Reliance Interests in Contract Damages Mark Pettit Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mark Pettit Jr., Private Advantage and Public Power: Reexamining the Expectation and Reliance Interests in Contract Damages, 38 Hastings L.J. 417 (1987). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol38/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. Article Private Advantage and Public Power: Reexamining the Expectation and Reliance Interests in Contract Damages by MARK PETTIT, JR.* Introduction Fifty years ago Fuller and Perdue asked why it is that in cases of breach of contract courts usually award "expectation" damages rather than "reliance" damages.I The authors defined these damages measures by their purposes.2 The object of the expectation measure "is to put the plaintiff in as good a position as he would have occupied had the defend- ant performed his promise."'3 The object of the reliance measure, on the other hand, is to "undo the harm" caused by reliance on a promise that was later broken, that is, "to put [the plaintif] in as good a position as he was in before the promise was made."'4 Fuller and Perdue concluded * Professor of Law, Boston University. A.B. -

The Doctrine of Commercial Impracticability in a Second-Best World

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1990 The Doctrine of Commercial Impracticability in a Second-Best World Alan O. Sykes Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Alan O. Sykes, "The Doctrine of Commercial Impracticability in a Second-Best World," 19 Journal of Legal Studies 43 (1990). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DOCTRINE OF COMMERCIAL IMPRACTICABILITY IN A SECOND-BEST WORLD ALAN 0. SYKES* ORDINARILY, a promisor who fails to perform a contractual obligation must pay damages to the promisee for breach of contract. But if the promisor is "unable" to perform because an extraordinary contingency materializes, and the promisor has not expressly assumed the risk of that contingency, the courts may relieve the promisor of the obligation to perform. At common law, such decisions fall under the doctrine of "im- possibility."' The Uniform Commercial Code (U.C.C.) adopts the term "impracticability" 2 which, for convenience, is used throughout this arti- cle to refer to both U.C.C. and common-law doctrine. This article explores the conditions under which a discharge of contrac- tual obligations is efficient following an event that makes performance "impracticable," such as an extraordinary increase in the cost of per- * Assistant Professor of Law, University of Chicago Law School. -

Specific Performance Versus Damages for Breach of Contract

ISSN 1045-6333 HARVARD JOHN M. OLIN CENTER FOR LAW, ECONOMICS, AND BUSINESS SPECIFIC PERFORMANCE VERSUS DAMAGES FOR BREACH OF CONTRACT Steven Shavell Discussion Paper No. 532 11/2005 Harvard Law School Cambridge, MA 02138 This paper can be downloaded without charge from: The Harvard John M. Olin Discussion Paper Series: http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/olin_center/ The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract_id=###### JEL Classifications: D8, K12 Specific Performance versus Damages for Breach of Contract Steven Shavell* Abstract: When would parties to a contract want performance to be specifically required, and when would they prefer payment of money damages to be the remedy for breach? This fundamental question is studied here, and an answer is provided that is based on a simple distinction between contracts to produce goods and contracts to convey property. Setting aside qualifications, the conclusion for breach of contracts to produce goods is that parties would tend to prefer the remedy of damages, essentially because of the problems that would be created under specific performance if production costs were high. In contrast, parties would often favor the remedy of specific performance for breach of contracts to convey property, in part because there can be no problems with production cost when property already exists. The conclusions reached shed light on the choices made between damages and specific performance under Anglo- American and under civil law systems, and they also suggest the desirability of certain changes in our legal doctrine. * Samuel R. Rosenthal Professor of Law and Economics, Harvard Law School. -

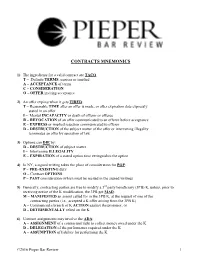

Contracts Mnemonics

CONTRACTS MNEMONICS 1) The ingredients for a valid contract are TACO: T – Definite TERMS, express or implied A – ACCEPTANCE of terms C – CONSIDERATION O – OFFER inviting acceptance 2) An offer expires when it gets TIRED: T – Reasonable TIME after an offer is made, or after expiration date expressly stated in an offer I – Mental INCAPACITY or death of offeror or offeree R – REVOCATION of an offer communicated to an offeree before acceptance E – EXPRESS or implied rejection communicated to offeror D – DESTRUCTION of the subject matter of the offer or intervening illegality terminates an offer by operation of law 3) Options can DIE by: D – DESTRUCTION of subject matter I – Intervening ILLEGALITY E – EXPIRATION of a stated option time extinguishes the option 4) In NY, a signed writing takes the place of consideration for POP: P – PRE–EXISTING duty O – Contract OPTIONS P – PAST consideration (which must be recited in the signed writing) 5) Generally, contracting parties are free to modify a 3rd party beneficiary (3PB) K, unless, prior to receiving notice of the K modification, the 3PB got MAD: M – MANIFESTED an assent called for in the 3PB K, at the request of one of the contracting parties (i.e., accepted a K offer arising from the 3PB K) A – Commenced a breach of K ACTION against the promisor, or D – DETRIMENTALLY relied on the K 6) Contract assignments may involve the ADA: A – ASSIGNMENT of a contractual right to collect money owed under the K D – DELEGATION of the performance required under the K A – ASSUMPTION of liability for performing