Santa Clarita: Chapter 20: Inside Elsmere Canyon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Certified List of Candidates

2006 Gubernatorial Primary - June 06, 2006 Candidate Contact Information Updated 05/01/2006 Page 1 of 153 GOVERNOR PHIL ANGELIDES Democratic 1331 21ST STREET SACRAMENTO, CA 95814 (916) 448-1998 (Business) (916) 448-1998 (Residence) (916) 446-0966 (FAX) WEBSITE: angelides.com Treasurer of the State of California BARBARA BECNEL Democratic 820 23RD ST. RICHMOND, CA 94804 (510) 860-5863 (Business) (510) 235-3112 (FAX) E-MAIL: [email protected] Executive Director JOE BROUILLETTE Democratic 7015 SIERRA PONDS LANE GRANITE BAY, CA 95746 (916) 791-4880 (Business) High School Teacher JERALD ROBERT GERST Democratic 35 ESTELLA CT. WALNUT CREEK, CA 94597 Medical Doctor/Physician VIBERT GREENE Democratic 6262 JARVIS AVE. NEWARK, CA 94560 (510) 794-5862 (Business) (510) 794-5862 (FAX) E-MAIL: [email protected] Engineer FRANK A. MACALUSO, JR. Democratic P.O. BOX 448 VISALIA, CA 93279 (559) 624-2600 (Business) E-MAIL: [email protected] Physician/Medical Doctor * Incumbent 2006 Gubernatorial Primary - June 06, 2006 Candidate Contact Information Updated 05/01/2006 Page 2 of 153 GOVERNOR MICHAEL STRIMLING Democratic 1334 GRAND AVE PIEDMONT, CA 94610 (510) 652-1810 (Business) (510) 652-1810 (Residence) (510) 652-1810 (FAX) WEBSITE: www.michaelstrimling.com E-MAIL: [email protected] Attorney STEVE WESTLY Democratic 550 COLLEGE AVE. PALO ALTO, CA 94306 (650) 843-0140 (Business) (650) 843-0748 (FAX) E-MAIL: [email protected] Controller of the State of California JEFFREY R. BURNS Republican 16787 BEACH BLVD. #626 HUNTINGTON BEACH, CA 92647 (714) 865-1259 (Business) (714) 969-7207 (Residence) E-MAIL: [email protected] General Contractor BILL CHAMBERS Republican P.O. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 01-6978 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States GARY A. EWING, Petitioner, vs. THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA, Respondent. On Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Appeal of the State of California, Second Appellate District BRIEF OF THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE LEGAL FOUNDATION; SECRETARY OF STATE BILL JONES; SENATORS DICK ACKERMAN, JIM BATTIN, JIM COSTA, RAY HAYNES, ROSS JOHNSON, WILLIAM J. “PETE” KNIGHT, TOM McCLINTOCK, BRUCE McPHERSON, CHARLES POOCHIGIAN; ASSEMBLYMEMBERS PATRICIA BATES, MIKE BRIGGS, DAVE COGDILL, DENNIS HOLLINGSWORTH, LYNNE LEACH, TIM LESLIE, DENNIS MOUNTJOY, ROBERT PACHECO, ANTHONY PESCETTI, GEORGE RUNNER, MARK WYLAND, PHIL WYMAN; AND FORMER ASSEMBLYMEMBER KEITH OLBERG AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT KENT S. SCHEIDEGGER CHARLES L. HOBSON Counsel of Record Criminal Justice Legal Fdn. 2131 L Street Sacramento, CA 95816 Phone: (916) 446-0345 Fax: (916) 446-1194 E-mail: [email protected] Attorneys for Amici Curiae Criminal Justice Legal Foundation (Intentionally left blank) QUESTION PRESENTED Does a sentence of 25 years to life for felony grand theft with several prior convictions for serious and violent felonies violate the Eighth Amendment in light of the highly deferential standard for reviewing prison sentences under that provision? (i) (Intentionally left blank) TABLE OF CONTENTS Question presented ................................ i Table of authorities ............................... v Interest of amici curiae ............................ 1 Summary of facts and case .......................... 2 Summary of argument ............................. 3 Argument ....................................... 5 I Any standard governing Eighth Amendment challenges to the proportionality of prison sentences must be very deferential ..................................... 5 II The conflicts between Solem and Rummel should be resolved by extending the deference accorded to punishment measures ............................ 7 A. -

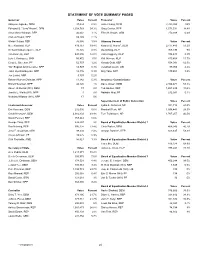

STATEMENT of VOTE, Summary Pages Amended 08/07/06 Xxix

STATEMENT OF VOTE, Summary Pages Amended 08/07/06 Governor Democratic Votes Percent Secretary of State Republican Votes Percent Barbara Becnel 66,550 2.7% Bruce McPherson 1,593,019 100.0% Frank A. Macaluso, Jr. 30,871 1.2% Secretary of State American Independent Votes Percent Jerald Robert Gerst 21,039 0.8% Joe Brouillette 42,077 1.7% Glenn McMillon, Jr. 32,289 100.0% Michael Strimling 35,122 1.4% Secretary of State Green Votes Percent Phil Angelides 1,202,884 48.0% Steve Westly 1,081,971 43.2% Forrest Hill 31,764 100.0% Vibert Greene 25,747 1.0% Secretary of State Libertarian Votes Percent Governor Republican Votes Percent Gail K. Lightfoot 16,870 100.0% Arnold Schwarzenegger 1,724,296 90.0% Secretary of State P and F Votes Percent Bill Chambers 65,488 3.4% Margie Akin 3,929 100.0% Jeffrey R. Burns 57,652 3.0% 68,663 3.6% Robert C. Newman II Controller Democratic Votes Percent Governor American Independent Votes Percent Joe Dunn 1,014,451 46.7% John Chiang 1,157,760 53.3% Edward C. Noonan 29,096 100.0% Controller Republican Votes Percent Governor Green Votes Percent Abel Maldonado 626,559 37.0% Peter Miguel Camejo 33,546 100.0% Bret R. Davis 91,760 5.4% Governor Libertarian Votes Percent David L. Harris 76,310 4.5% Art Olivier 16,445 100.0% Jim Stieringer 210,691 12.4% Tony Strickland 689,071 40.7% Governor P and F Votes Percent Controller American Independent Votes Percent Janice Jordan 3,849 100.0% Warren Mark Campbell 30,632 100.0% Lieutenant Governor Democratic Votes Percent Controller Green Votes Percent Jackie Speier 975,547 39.7% -

2014 Primary

STATEMENT OF VOTE SUMMARY PAGES Governor Votes Percent Treasurer Votes Percent Akinyemi Agbede, DEM 37,024 0.9% John Chiang, DEM 2,250,098 55% Edmund G. "Jerry" Brown*, DEM 2,354,769 54.3% Greg Conlon, REP 1,571,532 38.4% Alma Marie Winston, REP 46,042 1.1% Ellen H. Brown, GRN 270,388 6.6% Andrew Blount, REP 89,749 2.1% Glenn Champ, REP 76,066 1.8% Attorney General Votes Percent Neel Kashkari, REP 839,767 19.4% Kamala D. Harris*, DEM 2,177,480 53.2% Richard William Aguirre, REP 35,125 0.8% David King, REP 368,190 9% Tim Donnelly, REP 643,236 14.8% John Haggerty, REP 336,433 8.2% Luis J. Rodriguez, GRN 66,872 1.5% Phil Wyman, REP 479,468 11.7% Cindy L. Sheehan, PF 52,707 1.2% Ronald Gold, REP 504,091 12.3% "Bo" Bogdan Ambrozewicz, NPP 14,929 0.3% Jonathan Jaech, LIB 99,056 2.4% Janel Hyeshia Buycks, NPP 12,136 0.3% Orly Taitz, NPP 130,451 3.2% Joe Leicht, NPP 9,307 0.2% Rakesh Kumar Christian, NPP 11,142 0.3% Insurance Commissioner Votes Percent Robert Newman, NPP 44,120 1% Dave Jones*, DEM 2,106,671 53.1% Karen Jill Bernal (W/I), DEM 17 0% Ted Gaines, REP 1,651,242 41.6% Jimelle L. Walls (W/I), NPP 3 0% Nathalie Hrizi, PF 212,991 5.4% Nickolas Wildstar (W/I), NPP 17 0% Superintendent of Public Instruction Votes Percent Lieutenant Governor Votes Percent Lydia A. -

California State Senators and Officers

Record of State Senators 1849–2021 Name Politics Counties Representing Regular Sessions Served Aanestad, Sam R Butte, Colusa, Del Norte Glenn, Nevada, 2003–2010 Placer, Shasta, Siskiyou, Sutter, Tehama, Trinity, Yuba Abbott, J. P. R Marin, Contra Costa 27th (1887) Abell, Alexander G. Union San Francisco 14th (1863) 1 Abshire, F. Presley R Sonoma 1949–1958 Ackerman, Dick R Orange 2001–2008 2 Adams, Alonzo D Butte, Shasta 2nd (1851) Alarcón, Richard D Los Angeles 1999–2006 Allen, Ben D Los Angeles 2015–2021 Allen, Isaac D Yuba 9th (1858) A-L.D Yuba, Sutter 10th (1859) 3 Allen, James M. D, R Lassen, Modoc Shasta, Siskiyou 47th (1927), 48th (1929) D, R Del Norte, Siskiyou 49th (1931), 50th (1933) D Del Norte, Siskiyou 52nd (1937) Allen, Newton M. R Los Angeles 44th (1921) R, Prog. Los Angeles 45th (1923) R Los Angeles 46th (1925), 47th (1927) Record of State Senators 1849–2021 Name Politics Counties Representing Regular Sessions Served Alpert, Dede D San Diego 1997–2004 Alquist, Alfred E. D Santa Clara 1967–1982 D Alameda, San Benito, Santa Clara 1983–1984 D Santa Clara 1985–1996 Alquist, Elaine D Santa Clara 2005–2012 Anderson, A. P. R Alameda 43rd (1919), 44th (1921) 4 Anderson, Alexander D Tuolumne 3rd (1852) Anderson, Francis Union Sierra 14th (1863) Anderson, James D Placer 9th (1858), 11th (1860) Anderson, Joel R Riverside, San Diego 2011–2014 R San Diego 2015–2018 Anderson, John N. R Riverside, Orange 36th (1905), 37th (1907) R Riverside, Orange, Imperial 40th (1913), 41st (1915) Anderson, William L. D Lake, Napa, Sonoma 23rd (1880), 24th (1881) Andross, Moses C. -

Certified List of Candidates-Shortlist

Statewide Direct Primary Election - June 3, 2014 Official Certified List of Candidates 3/27/2014 Page 1 of 49 GOVERNOR AKINYEMI AGBEDE Democratic Doctoral Student EDMUND G. "JERRY" BROWN* Democratic Governor of California RICHARD WILLIAM AGUIRRE Republican Real Estate Investor ANDREW BLOUNT Republican Mayor/Businessperson GLENN CHAMP Republican Business Owner/Engineer TIM DONNELLY Republican California State Assemblyman NEEL KASHKARI Republican Businessman ALMA MARIE WINSTON Republican Project Funding CEO LUIS J. RODRIGUEZ Green Author/Community Organizer CINDY L. SHEEHAN Peace and Freedom Author/Non-Profit Director "BO" BOGDAN AMBROZEWICZ No Party Preference Small Business Owner JANEL HYESHIA BUYCKS No Party Preference Minister/Business Owner RAKESH KUMAR CHRISTIAN No Party Preference Small Business Owner JOE LEICHT No Party Preference Golf Course Operator ROBERT NEWMAN No Party Preference Psychologist/Farmer * Incumbent Statewide Direct Primary Election - June 3, 2014 Official Certified List of Candidates 3/27/2014 Page 2 of 49 LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR ERIC KOREVAAR Democratic Scientist/Businessman/Parent GAVIN NEWSOM* Democratic Lieutenant Governor DAVID FENNELL Republican Entrepreneur RON NEHRING Republican Small Businessman/Educator GEORGE YANG Republican Father/Software Developer JENA F. GOODMAN Green Student AMOS JOHNSON Peace and Freedom Security Guard ALAN REYNOLDS Americans Elect Commissioner/Engineer/Businessman * Incumbent Statewide Direct Primary Election - June 3, 2014 Official Certified List of Candidates 3/27/2014 Page 3 of 49 SECRETARY OF STATE DEREK CRESSMAN Democratic Voting Rights Advocate JEFFREY H. DROBMAN Democratic Computer Scientist/Engineer ALEX PADILLA Democratic California State Senator LELAND YEE Democratic California State Senator ROY ALLMOND Republican California State Employee PETE PETERSON Republican Educator/Institute Director DAVID CURTIS Green Dad/Designer DAN SCHNUR No Party Preference Political Involvement Educator CONTROLLER TAMMY D.