The Lost Decade Updating Austerity in the United Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Smokescreen Budget in the House of Commons Library George Osborne’S Claim That His Is a One Nation Budget Should Ensure Its Being Placed in the Fiction Section

The Smokescreen Budget In the House of Commons Library George Osborne’s claim that his is a One Nation budget should ensure its being placed in the Fiction Section. Low-paid basic workers did not (for political purposes) exist, or had no right to exist, or could live on thin air. Yet it is on these that the world’s life finally depends. In the book of Ecclesiasticus, 38, the honour due to the doctor and the intellectual are duly acknowledged. The question is then raised ‘whose work sustains the fabric of the world’ – keeps its essential life going from one day to another. The answer is the basic worker. It is a twisted society which does not acknowledge and honour that. Osborne’s is the budget of a twisted society, as far from reality as is Alice in Wonderland. When, in a budget speech, a smokescreen is deliberately put in place, the wise will peer underneath to see what realities are being concealed. How is this done? Osborne used shock tactics. A Tory budget anticipating a living wage of £9 an hour! – enough to distract the attention of the unwary from the nitty-gritty substance! Yet, even at that point, awkward thoughts might have caused the wary to pause. One is that this will cost the government nothing. Another is that, if, at one fell swoop, the government could establish a living wage in the future why was this not done when basic wages were so low as to leave workers living on the margins. A third is that the target is distant enough, so that, by the time the date is reached, it may amount to no more than a minimum wage arrangement. -

Mundella Papers Scope

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 6 - 9, MS 22 Title: Mundella Papers Scope: The correspondence and other papers of Anthony John Mundella, Liberal M.P. for Sheffield, including other related correspondence, 1861 to 1932. Dates: 1861-1932 (also Leader Family correspondence 1848-1890) Level: Fonds Extent: 23 boxes Name of creator: Anthony John Mundella Administrative / biographical history: The content of the papers is mainly political, and consists largely of the correspondence of Mundella, a prominent Liberal M.P. of the later 19th century who attained Cabinet rank. Also included in the collection are letters, not involving Mundella, of the family of Robert Leader, acquired by Mundella’s daughter Maria Theresa who intended to write a biography of her father, and transcriptions by Maria Theresa of correspondence between Mundella and Robert Leader, John Daniel Leader and another Sheffield Liberal M.P., Henry Joseph Wilson. The collection does not include any of the business archives of Hine and Mundella. Anthony John Mundella (1825-1897) was born in Leicester of an Italian father and an English mother. After education at a National School he entered the hosiery trade, ultimately becoming a partner in the firm of Hine and Mundella of Nottingham. He became active in the political life of Nottingham, and after giving a series of public lectures in Sheffield was invited to contest the seat in the General Election of 1868. Mundella was Liberal M.P. for Sheffield from 1868 to 1885, and for the Brightside division of the Borough from November 1885 to his death in 1897. -

Web of Power

Media Briefing MAIN HEADING PARAGRAPH STYLE IS main head Web of power SUB TITLE PARAGRAPH STYLE IS main sub head The UK government and the energy- DATE PARAGRAPH STYLE IS date of document finance complex fuelling climate change March 2013 Research by the World Development Movement has Government figures embroiled in the nexus of money and revealed that one third of ministers in the UK government power fuelling climate change include William Hague, are linked to the finance and energy companies driving George Osborne, Michael Gove, Oliver Letwin, Vince Cable climate change. and even David Cameron himself. This energy-finance complex at the heart of government If we are to move away from a high carbon economy, is allowing fossil fuel companies to push the planet to the government must break this nexus and regulate the the brink of climate catastrophe, risking millions of lives, finance sector’s investment in fossil fuel energy. especially in the world’s poorest countries. SUBHEAD PARAGRAPH STYLE IS head A Introduction The world is approaching the point of no return in the Energy-finance complex in figures climate crisis. Unless emissions are massively reduced now, BODY PARAGRAPH STYLE IS body text Value of fossil fuel shares on the London Stock vast areas of the world will see increased drought, whole Exchange: £900 billion1 – higher than the GDP of the countries will be submerged and falling crop yields could whole of sub-Saharan Africa.2 mean millions dying of hunger. But finance is continuing to flow to multinational fossil fuel companies that are Top five UK banks’ underwrote £170 billion in bonds ploughing billions into new oil, gas and coal energy. -

94 Spring 2017 Journal of Liberal History Issue 94: Spring 2017 the Journal of Liberal History Is Published Quarterly by the Liberal Democrat History Group

For the study of Liberal, SDP and Issue 94 / Spring 2017 / £7.50 Liberal Democrat history Journal of LiberalHI ST O R Y War authors Alan Mumford Churchill and Lloyd George Liberal authors on the First World War? David Dutton Sir Walter Runciman and the Runciman papers at Elshieshields Tower Neil Stockley Coalition: Could Liberal Democrats have handled it better? Meeting report J. Graham Jones Liberal archives at the Churchill Archives Centre Michael Meadowcroft The Lib–Lab Pact Book review Liberal Democrat History Group Liberal History 350 years of party history in 32 pages The Liberal Democrat History Group’s pamphlet, Liberal History: A concise history of the Liberal Party, SDP and Liberal Democrats, has been revised and updated to include the coalition and its impact and the 2015 election and its aftermath. The essential introduction to Liberal history, now updated to March 2017. Liberal History is available to Journal of Liberal History subscribers for the special price of £2.40 (normal price £3.00) plus £0.60 P&P. Order via our online shop (www.liberalhistory.org.uk/shop/), or by post from LDHG, 54 Midmoor Road, London SW12 0EN (cheque payable at ‘Liberal Democrat History Group’). The booklet makes an ideal gift for new party members; we can offer a 50 per cent discount for bulk orders of 40 or more copies. Contact the Editor on [email protected]. Journal of Liberal History: special issues The Liberal Party and the First World War Journal 87 (summer 2015) Includes: Did the Great War really kill the Liberal Party?; The long shadow of war; The Liberal Party, the Labour Party and the First World War; John Morley’s resignation in August 1914; Gilbert Murray v. -

The Power of the Prime Minister

Research Paper Research The Power of the Prime Minister 50 Years On George Jones THE POWER OF THE PRIME MINISTER 50 YEARS ON George Jones Emeritus Professor of Government London School of Economics & Political Science for The Constitution Society Based on a lecture for the Institute of Contemporary British History, King’s College, London, 8 February 2016 First published in Great Britain in 2016 by The Constitution Society Top Floor, 61 Petty France London SW1H 9EU www.consoc.org.uk © The Constitution Society ISBN: 978-0-9954703-1-6 © George Jones 2016. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. THE POWER OF THE PRIME MINISTER 3 Contents About the Author 4 Foreword 5 Introduction 9 Contingencies and Resource Dependency 11 The Formal Remit and Amorphous Convention 13 Key Stages in the Historical Development of the Premiership 15 Biographies of Prime Ministers are Not Enough 16 Harold Wilson 17 Tony Blair – almost a PM’s Department 19 David Cameron – with a department in all but name 21 Hung Parliament and Coalition Government 22 Fixed-term Parliaments Act, 2011 25 Party Dynamics 26 Wilson and Cameron Compared 29 Enhancing the Prime Minister 37 Between Wilson and Cameron 38 Conclusions 39 4 THE POWER OF THE PRIME MINISTER About the Author George Jones has from 2003 been Emeritus Professor of Government at LSE where he was Professor of Government between 1976 and 2003. -

Survey Report

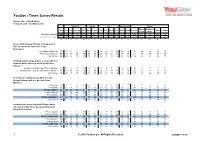

YouGov / Times Survey Results Sample Size: 1688 GB Adults Fieldwork: 20th - 21st March 2016 Vote 2015 Gender Age Social Grade Region Rest of Midlands / Total Con Lab Lib Dem UKIP Male Female 18-24 25-49 50-64 65+ ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland South Wales Weighted Sample 1688 476 393 102 164 817 871 196 722 415 354 962 726 202 560 363 408 156 Unweighted Sample 1688 479 425 116 162 726 962 198 648 430 412 1043 645 182 562 360 417 167 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % Do you think George Osborne is doing a good job or a bad job as Chancellor of the Exchequer? He is doing a good job 17 41 3 14 6 21 13 19 14 17 20 20 13 15 20 16 15 15 He is doing a bad job 58 31 82 68 75 60 56 49 55 64 64 59 57 51 55 58 63 66 Don't know 25 29 15 19 19 19 31 32 31 19 16 21 30 34 25 27 22 19 Thinking about George Osborne, do you think he would or would not be up to the job of Prime Minister? Would be up to the job of Prime Minister 8 14 3 10 2 9 7 8 8 7 8 8 8 12 7 7 8 8 Would not be up to the job of Prime Minister 73 66 86 79 86 78 69 65 70 78 79 76 70 62 75 73 76 75 Don't know 19 20 11 10 13 13 25 27 23 15 12 16 22 25 18 20 16 17 How likely or unlikely do you think it is that George Osborne will ever become Prime Minister? Very likely 1 1 1 0 1 2 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 2 Fairly likely 12 14 11 22 7 15 9 11 11 14 12 14 8 14 12 11 11 14 TOTAL LIKELY 13 15 12 22 8 17 10 12 13 15 13 15 9 16 13 12 12 16 Fairly unlikely 37 46 38 44 34 39 36 35 30 44 44 40 33 32 38 42 36 29 Very unlikely 30 23 34 25 41 31 28 26 31 25 33 26 34 23 31 26 33 31 TOTAL UNLIKELY 67 69 -

APD – 10 Key Points Briefing From

Air Passenger Duty Ten Key Points 1. APD was introduced in 1994 by Ken Clarke, the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, not as an environmental tax but because he considered the aviation industry to be lightly taxed compared to other sectors, largely arising from its exemption from fuel duty and VAT. 2. It was initially set at £5.00 for short haul economy travel, which accounts for more than three quarters of all air travel. In 1997 Ken Clarke doubled APD to £10.00 for short haul economy flights. 3. Gordon Brown halved the short haul economy rate of APD in 2001, put it back up again to £10.00 in 2007 and Alistair Darling raised it to £11.00 in 2009. George Osborne increased it to £12.00 in 2010. There was no increase in 2011 but it was raised to £13.00 in April 2012. Thus, for the vast majority of passengers APD has increased by just £3.00 (30%) over the past 15 years. 4. APD is payable only on departure from a UK airport and so the basic Band A rate of £13.00 is for a round trip to an overseas destination. APD is however payable on both legs of a domestic round trip within the UK. 5. APD raised £2.6 billion for public finances in 2011/12 and this is planned to increase to £3.9 billion by 2015/16. APD would, however, need to rise to four times its current level to offset the value of the industry’s exemption from fuel duty and VAT. -

Rt Hon Greg Clark MP

Rt Hon Greg Clark MP Minister of State for Cities, Cabinet Office and Minister of State for Universities and Science, Department for Business, Innovation and Skills Constituency: Tunbridge Wells, South East Majority: 15,576 Party: Conservative Westminster Rt Hon Greg Clark MP House of Commons London SW1A 0AA Tel: 020 7219 6977 E-mail: Create email Web: Visit website Relevant contributions In 2007, Clark signed a pro-homeopathic hospitals EDM As cities minister, Clark announced a £1bn investment strategy for Cambridgeshire. The 2014 investment sought to help Cambridge and the surrounding area become the UK’s silicon valley, helping it build on its “world class research facilities” In 2008, he took part in a debate on the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill and expressed concern over the invasiveness of regenerative tissue techniques, especially if performed on children A summary of his relevant Parliamentary contributions can be found here. Responsibilities As Minister of State for Cities, Cabinet Office Leads local growth and cities policy, and works with the Deputy Prime Minister on constitutional affairs. As Minister of State for Universities and Science, Department for Business, Innovation and Skills Looking across all departmental business at strategic priorities; higher education (including Higher Education Funding Council for England and Student Loans Company); science and research (including Research Councils); life sciences; innovation; Technology Strategy Board; Energy Technologies Institute; the National Measurement Office; -

Web of Power the UK Government and the Energy- Finance Complex Fuelling Climate Change March 2013

Media briefing Web of power The UK government and the energy- finance complex fuelling climate change March 2013 Research by the World Development Movement has Government figures embroiled in the nexus of money and revealed that one third of ministers in the UK government power fuelling climate change include William Hague, are linked to the finance and energy companies driving George Osborne, Michael Gove, Oliver Letwin, Vince Cable climate change. and even David Cameron himself. This energy-finance complex at the heart of government If we are to move away from a high carbon economy, is allowing fossil fuel companies to push the planet to the government must break this nexus and regulate the the brink of climate catastrophe, risking millions of lives, finance sector’s investment in fossil fuel energy. especially in the world’s poorest countries. Introduction The world is approaching the point of no return in the Energy-finance complex in figures climate crisis. Unless emissions are massively reduced now, Value of fossil fuel shares on the London Stock vast areas of the world will see increased drought, whole Exchange: £900 billion1 – higher than the GDP of the countries will be submerged and falling crop yields could whole of sub-Saharan Africa.2 mean millions dying of hunger. But finance is continuing to flow to multinational fossil fuel companies that are Top five UK banks’ underwrote £170 billion in bonds ploughing billions into new oil, gas and coal energy. and share issues for fossil fuel companies 2010-12 – more than 11 times the amount the UK contributed in The vested interests of big oil, gas and coal mining climate finance for developing countries.3 companies are in favour of the status quo. -

A Forgotten Lib–Con Alliance

For the study of Liberal, SDP and Issue 79 / Summer 2013 / £6.00 Liberal Democrat history Journal of LiberalHI ST O R Y A forgotten Lib–Con alliance Alun Wyburn-Powell The Constitutionalists and the 1924 election A new party or a worthless coupon? David Dutton ‘A nasty, deplorable little incident in our political life’ The Dumfries Standard, 1957 David Cloke David Lloyd George: the legacy Meeting report James Fargher The South African war and its effect on the Liberal alliance Kenneth O. Morgan The relevance of Henry Richard The ‘apostle of peace’ Liberal Democrat History Group 2 Journal of Liberal History 79 Summer 2013 Journal of Liberal History Issue 79: Summer 2013 The Journal of Liberal History is published quarterly by the Liberal Democrat History Group. ISSN 1479-9642 Liberal history news 4 Editor: Duncan Brack Lloyd George commemorations; plaque to Lord john Russell; Gladstone statue Deputy Editor: Tom Kiehl unveiled in Seaforth Assistant Editor: Siobhan Vitelli Biographies Editor: Robert Ingham Reviews Editor: Dr Eugenio Biagini A forgotten Liberal–Conservative alliance 6 Contributing Editors: Graham Lippiatt, Tony Little, The Constitutionalists and the 1924 election – a new party or a worthless York Membery coupon? by Alun Wyburn-Powell Patrons Letters to the Editor 15 Dr Eugenio Biagini; Professor Michael Freeden; Honor Balfour (Michael Meadowcroft and Hugh Pagan) Professor John Vincent Editorial Board Liberal history quiz 2012 15 Dr Malcolm Baines; Dr Ian Cawood; Matt Cole; Dr Roy The answers (questions in issue 78) Douglas; Dr David Dutton; Prof. David Gowland; Prof. Richard Grayson; Dr Michael Hart; Peter Hellyer; Dr ‘A nasty, deplorable little incident in our political 16 Alison Holmes; Dr J. -

The Spending Challenge: How to Cut Spending While Maintaining Quality

The Spending Challenge: how to cut spending while maintaining quality Julian McCrae BRIEFING PAPER September 2016 Summary The months since the EU referendum have been tumultuous times in British politics. This Autumn, Theresa May’s Government will have to set out how it meets many long-standing problems. But it is doing this in a surprising new context. As our new polling shows, the public are markedly more willing to believe that politicians will run government professionally and are capable of implementing the best policies for Britain. Brexit brings many new challenges to governing, but the old problems have not gone away. The Government still faces a huge spending challenge. While the Government has made clear that it is prepared to borrow more than planned should the economy deteriorate, Theresa May has also committed herself to continuing George Osborne’s cuts to day-to-day spending. As she has set herself against substantial tax rises, such cuts remain the only long-term way to balance Britain’s books. At the same time, none of the pressures on public services have gone away. The performance of key parts of the NHS, such as A&E, is still declining. The pressures on areas as diverse as social care or the prison service remain both obvious and severe. Meanwhile, polling shows that the public’s appetite for further austerity appears to be declining. And Theresa May has inherited manifesto pledges, like the seven-day NHS, that commit her to not just maintaining, but increasing, the scope of public services. In this context, if it wants to justify the public’s increased trust in its ability to deliver, then the Government needs to urgently set out a credible plan for implementing its planned cuts to day-to-day spending, while maintaining service quality. -

George Osborne OBR Distributional Analysis

-- ..·--- . HM Treasury, I Horse Guards Road, London, SW I A 2HQ l September 2015 Andrew Tyrie MP House of Commons London SW1A OAA Followibtter~s:. I am writing to address your concerns over the timing of the appointment of the Chair of the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), alongside your request for additional distributional analysis. You will have received the environmental information you further requested in a previous letter of 21 August. OBR appointment With regards to the appointment of the Chair of the OBR, I notified you of my decision earlier this month. I hope you will appreciate tbe special circumstances on this occasion, with the election and the Summer Budget taking place this year. I am grateful for your support and that of Committee members in scheduling the pre-appointment hearing in due course. Distributional analysis You asked that I make available distributional analysis of the impacts of policy changes up to and including the Summer Budget, beyond the quintile analysis which I agreed to provide at the Committee hearing on 21 July and which I subsequently placed on the gov.uk website and have attached to this letter for reference. As I set out in the Committee hearing, the Government continues to present an unprecedented level of transparency about the distribution of public spending, and I welcome the Committee's continuing interest in this analysis. In this Parliament, the Government has taken a decision to present the distribution of public spending and taxes that affect households both before and after the policy changes we have made since 2010.