Available for Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plano De Manejo Da Reserva Biológica Nascentes Da Serra Do Cachimbo

Apresentação Plano de Manejo da Reserva Biológica Nascentes da Serra do Cachimbo 2009 MINISTÉRIO DO MEIO AMBIENTE INSTITUTO CHICO MENDES DE CONSERVAÇÃO DA BIODIVERSIDADE DIRETORIA DE UNIDADES DE CONSERVAÇÃO DE PROTEÇÃO INTEGRAL PLANO DE MANEJO DA RESERVA BIOLÓGICA NASCENTES DA SERRA DO CACHIMBO APRESENTAÇÃO Brasília, 2009 PRESIDÊNCIA DA REPÚBLICA Luis Inácio Lula da Silva MINISTÉRIO DO MEIO AMBIENTE - MMA Carlos Minc Baumfeld - Ministro INSTITUTO CHICO MENDES DE CONSERVAÇÃO DA BIODIVERSIDADE - ICMBio Rômulo José Fernandes Mello - Presidente DIRETORIA DE UNIDADES DE CONSERVAÇÃO DE PROTEÇÃO INTEGRAL – DIREP Ricardo José Soavinski - Diretor COORDENAÇÃO GERAL DE UNIDADES DE CONSERVAÇÃO DE PROTEÇÃO INTEGRAL Maria Iolita Bampi - Coordenador COORDENAÇÃO DE PLANO DE MANEJO – CPLAM Carlos Henrique Fernandes - Coordenador COORDENAÇÃO DO BIOMA AMAZÔNIA - COBAM Lilian Hangae - Coordenador Brasília, 2009 CRÉDITOS TÉCNICOS E INSTITUCIONAIS Equipe de Elaboração do Plano de Manejo da Reserva Biológica Nascentes da Serra do Cachimbo Coordenação Geral Gustavo Vasconcellos Irgang – Instituto Centro de Vida - ICV Coordenação Técnica Jane M. de O. Vasconcellos – Instituto Centro de Vida Marisete Catapan – WWF Brasil Coordenação da Avaliação Ecológica Rápida Jan Karel Felix Mähler Junior Supervisão e Acompanhamento Técnico do ICMBio Allan Razera e Lílian Hangae Equipe de Consultores Responsáveis pelas Áreas Temáticas Meio Físico Gustavo Vasconcellos Irgang Roberta Roxilene dos Santos Jean Carlo Correa Figueira Vegetação Marcos Eduardo G. Sobral Ayslaner Victor -

Catalogue of the Amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and Annotated Species List, Distribution, and Conservation 1,2César L

Mannophryne vulcano, Male carrying tadpoles. El Ávila (Parque Nacional Guairarepano), Distrito Federal. Photo: Jose Vieira. We want to dedicate this work to some outstanding individuals who encouraged us, directly or indirectly, and are no longer with us. They were colleagues and close friends, and their friendship will remain for years to come. César Molina Rodríguez (1960–2015) Erik Arrieta Márquez (1978–2008) Jose Ayarzagüena Sanz (1952–2011) Saúl Gutiérrez Eljuri (1960–2012) Juan Rivero (1923–2014) Luis Scott (1948–2011) Marco Natera Mumaw (1972–2010) Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(1) [Special Section]: 1–198 (e180). Catalogue of the amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and annotated species list, distribution, and conservation 1,2César L. Barrio-Amorós, 3,4Fernando J. M. Rojas-Runjaic, and 5J. Celsa Señaris 1Fundación AndígenA, Apartado Postal 210, Mérida, VENEZUELA 2Current address: Doc Frog Expeditions, Uvita de Osa, COSTA RICA 3Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales, Museo de Historia Natural La Salle, Apartado Postal 1930, Caracas 1010-A, VENEZUELA 4Current address: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Río Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Laboratório de Sistemática de Vertebrados, Av. Ipiranga 6681, Porto Alegre, RS 90619–900, BRAZIL 5Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, Altos de Pipe, apartado 20632, Caracas 1020, VENEZUELA Abstract.—Presented is an annotated checklist of the amphibians of Venezuela, current as of December 2018. The last comprehensive list (Barrio-Amorós 2009c) included a total of 333 species, while the current catalogue lists 387 species (370 anurans, 10 caecilians, and seven salamanders), including 28 species not yet described or properly identified. Fifty species and four genera are added to the previous list, 25 species are deleted, and 47 experienced nomenclatural changes. -

Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 8

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Publications Plant Health Inspection Service 2012 Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 8. Eleutherodactylus planirostris, the Greenhouse Frog (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae) Christina A. Olson Utah State University, [email protected] Karen H. Beard Utah State University, [email protected] William C. Pitt National Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc Olson, Christina A.; Beard, Karen H.; and Pitt, William C., "Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 8. Eleutherodactylus planirostris, the Greenhouse Frog (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae)" (2012). USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications. 1174. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/1174 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 8. Eleutherodactylus planirostris, the Greenhouse Frog (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae)1 Christina A. Olson,2 Karen H. Beard,2,4 and William C. Pitt 3 Abstract: The greenhouse frog, Eleutherodactylus planirostris, is a direct- developing (i.e., no aquatic stage) frog native to Cuba and the Bahamas. It was introduced to Hawai‘i via nursery plants in the early 1990s and then subsequently from Hawai‘i to Guam in 2003. The greenhouse frog is now widespread on five Hawaiian Islands and Guam. -

Species Diversity and Conservation Status of Amphibians in Madre De Dios, Southern Peru

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 4(1):14-29 Submitted: 18 December 2007; Accepted: 4 August 2008 SPECIES DIVERSITY AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF AMPHIBIANS IN MADRE DE DIOS, SOUTHERN PERU 1,2 3 4,5 RUDOLF VON MAY , KAREN SIU-TING , JENNIFER M. JACOBS , MARGARITA MEDINA- 3 6 3,7 1 MÜLLER , GIUSEPPE GAGLIARDI , LILY O. RODRÍGUEZ , AND MAUREEN A. DONNELLY 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, 11200 SW 8th Street, OE-167, Miami, Florida 33199, USA 2 Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] 3 Departamento de Herpetología, Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Avenida Arenales 1256, Lima 11, Perú 4 Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, California 94132, USA 5 Department of Entomology, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, California 94118, USA 6 Departamento de Herpetología, Museo de Zoología de la Universidad Nacional de la Amazonía Peruana, Pebas 5ta cuadra, Iquitos, Perú 7 Programa de Desarrollo Rural Sostenible, Cooperación Técnica Alemana – GTZ, Calle Diecisiete 355, Lima 27, Perú ABSTRACT.—This study focuses on amphibian species diversity in the lowland Amazonian rainforest of southern Peru, and on the importance of protected and non-protected areas for maintaining amphibian assemblages in this region. We compared species lists from nine sites in the Madre de Dios region, five of which are in nationally recognized protected areas and four are outside the country’s protected area system. Los Amigos, occurring outside the protected area system, is the most species-rich locality included in our comparison. -

A New Family of Diverse Skin Peptides from the Microhylid Frog Genus Phrynomantis

molecules Article A New Family of Diverse Skin Peptides from the Microhylid Frog Genus Phrynomantis Constantijn Raaymakers 1,2, Benoit Stijlemans 3,4, Charlotte Martin 5, Shabnam Zaman 1 , Steven Ballet 5, An Martel 2, Frank Pasmans 2 and Kim Roelants 1,* 1 Amphibian Evolution Lab, Biology Department, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Pleinlaan 2, 1050 Elsene, Belgium; [email protected] (C.R.); [email protected] (S.Z.) 2 Wildlife Health Ghent, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ghent University, Salisburylaan 133, 9820 Merelbeke, Belgium; [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (F.P.) 3 Unit of Cellular and Molecular Immunology, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Pleinlaan 2, 1050 Elsene, Belgium; [email protected] 4 Myeloid Cell Immunology Lab, VIB Centre for Inflammation Research, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Pleinlaan 2, 1050 Elsene, Belgium 5 Research Group of Organic Chemistry, Department of Chemistry and Department of Bio-engineering Sciences, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Pleinlaan 2, 1050 Elsene, Belgium; [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (S.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-26293410 Received: 17 January 2020; Accepted: 18 February 2020; Published: 18 February 2020 Abstract: A wide range of frogs produce skin poisons composed of bioactive peptides for defence against pathogens, parasites and predators. While several frog families have been thoroughly screened for skin-secreted peptides, others, like the Microhylidae, have remained mostly unexplored. Previous studies of microhylids found no evidence of peptide secretion, suggesting that this defence adaptation was evolutionarily lost. We conducted transcriptome analyses of the skins of Phrynomantis bifasciatus and Phrynomantis microps, two African microhylid species long suspected to be poisonous. -

For Submission As a Note Green Anole (Anolis Carolinensis) Eggs

For submission as a Note Green Anole (Anolis carolinensis) Eggs Associated with Nest Chambers of the Trap Jaw Ant, Odontomachus brunneus Christina L. Kwapich1 1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Massachusetts Lowell One University Ave., Lowell, Massachusetts, USA [email protected] Abstract Vertebrates occasionally deposit eggs in ant nests, but these associations are largely restricted to neotropical fungus farming ants in the tribe Attini. The subterranean chambers of ponerine ants have not previously been reported as nesting sites for squamates. The current study reports the occurrence of Green Anole (Anolis carolinensis) eggs and hatchlings in a nest of the trap jaw ant, Odontomachus brunneus. Hatching rates suggest that O. brunneus nests may be used communally by multiple females, which share spatial resources with another recently introduced Anolis species in their native range. This nesting strategy is placed in the context of known associations between frogs, snakes, legless worm lizards and ants. Introduction Subterranean ant nests are an attractive resource for vertebrates seeking well-defended cavities for their eggs. To access an ant nest, trespassers must work quickly or rely on adaptations that allow them to overcome the strict odor-recognition systems of ants. For example the myrmecophilous frog, Lithodytes lineatus, bears a chemical disguise that permits it to mate and deposit eggs deep inside the nests of the leafcutter ant, Atta cephalotes, without being bitten or harassed. Tadpoles inside nests enjoy the same physical and behavioral protection as the ants’ own brood, in a carefully controlled microclimate (de Lima Barros et al. 2016, Schlüter et al. 2009, Schlüter and Regös 1981, Schlüter and Regös 2005). -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. -

*For More Information, Please See

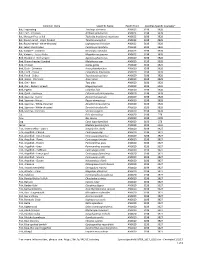

Common Name Scientific Name Health Point Specifies-Specific Course(s)* Bat, Frog-eating Trachops cirrhosus AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Fruit - Jamaican Artibeus jamaicensis AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Mexican Free-tailed Tadarida brasiliensis mexicana AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Round-eared - stripe-headed Tonatia saurophila AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Round-eared - white-throated Lophostoma silvicolum AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Seba's short-tailed Carollia perspicillata AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Vampire - Common Desmodus rotundus AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Vampire - Lesser False Megaderma spasma AN0023 3198 3928 Bird, Blackbird - Red-winged Agelaius phoeniceus AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Brown-headed Cowbird Molothurus ater AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Chicken Gallus gallus AN0020 3198 3529 Bird, Duck - Domestic Anas platyrhynchos AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Finch - House Carpodacus mexicanus AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Finch - Zebra Taeniopygia guttata AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Goose - Domestic Anser anser AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Owl - Barn Tyto alba AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Owl - Eastern Screech Megascops asio AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Pigeon Columba livia AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Quail - Japanese Coturnix coturnix japonica AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Sparrow - Harris' Zonotrichia querula AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Sparrow - House Passer domesticus AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Sparrow - White-crowned Zonotrichia leucophrys AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Sparrow - White-throated Zonotrichia albicollis AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Starling - Common Sturnus vulgaris AN0020 3198 3928 Cat Felis domesticus AN0020 3198 279 Cow Bos taurus -

Amphibia, Anura, Dendrobatidae, Allobates Femoralis (Boulenger, 1884): First Confirmed Country Records, Venezuela

ISSN 1809-127X (online edition) © 2010 Check List and Authors Chec List Open Access | Freely available at www.checklist.org.br Journal of species lists and distribution N Allobates femoralis ISTRIBUTIO Amphibia, Anura, Dendrobatidae, D Venezuela (Boulenger, 1884): First confirmed country records, RAPHIC G César L. Barrio-Amorós and Juan Carlos Santos 2 EO 1* G N O 1 Fundación Andígena, [email protected] postal 210, 5101-A. Mérida, Venezuela. OTES 2 University of Texas at Austin, Integrative Biology. 1 University Station C0930. Austin, TX 78705, USA. N * Corresponding author E-mail: Abstract: Allobates femoralis analized advertisement calls taken at two Venezuelan localities. The presence of the dendrobatid frog in Venezuela is herein confirmed though recorded and Allobates femoralis is a common dendrobatid frog widely distributed throughout the Amazon and Guianas in Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil, French Guiana, series of four notes at Las Claritas is 0.52 sec; the dominant Suriname and Guyana (Lötters et al. frequency is at 2954 Hz and the fundamental frequency is error, based on KU (Natural History 2007). Museum, The firstUniversity report of this species from Venezuela (Duellman 1997) was in was later recognized as Ameerega guayanensis (Barrio- Amorósof Kansas, 2004). Lawrence, Ameerega Kansas, guayanensisUSA) 167335. was This describedspecimen 2004).for populations Today however, of eastern this Venezuelataxon validity and is some questionable authors considered it as valid (Schulte 1999; Barrio-Amorós A.(J.C. (picta) Santos guayanensis unpublished because data). itSince is theno validnomenclatural available act was yet performed, we herein use the combinationAllobates femoralis was removed from the Venezuelan checklist name for those populations. -

Hymenoptera, Formicidae) Fauna of Senegal

Journal of Insect Biodiversity 5(15): 1-16, 2017 http://www.insectbiodiversity.org RESEARCH ARTICLE A preliminary checklist of the ant (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) fauna of Senegal Lamine Diamé1,2*, Brian Taylor3, Rumsaïs Blatrix4, Jean-François Vayssières5, Jean- Yves Rey1,5, Isabelle Grechi6, Karamoko Diarra2 1ISRA/CDH, BP 3120, Dakar, Senegal; 2UCAD, BP 7925, Dakar, Senegal; 311Grazingfield, Wilford, Nottingham, NG11 7FN, United Kingdom; 4CEFE UMR 5175, CNRS – Université de Montpellier – Université Paul Valéry Montpellier – EPHE, 1919 route de Mende, 34293 Montpellier Cedex 5, France; 5CIRAD; UPR HortSys; Montpellier, France; 6CIRAD, UPR HortSys, F-97410 Saint-Pierre, La Réunion, France. *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: This work presents the first checklist of the ant species of Senegal, based on a review of the literature and on recent thorough sampling in Senegalese orchard agrosystems during rainy and dry seasons. Eighty-nine species belonging to 31 genera and 9 subfamilies of Formicidae are known. The most speciose genera were Monomorium Mayr, 1855, and Camponotus Mayr, 1861, with 13 and 12 species, respectively. The fresh collection yielded 31 species recorded for the first time in Senegal, including two undescribed species. The composition of the ant fauna reflects the fact that Senegal is in intermediate ecozone between North Africa and sub-Saharan areas, with some species previously known only from distant locations, such as Sudan. Key words: Ants, checklist, new records, sub-Saharan country, Senegal. Introduction Information on the ant fauna of Senegal is mostly known from scattered historical records, and no synthetic list has been published. The first record dates from 1793 while the most recent was in 1987 (see Table 1). -

The Coexistence

Myrmecological News 10 27-28 Vienna, September 2007 Cooperative self-defence: Matabele ants (Pachycondyla analis) against African driver ants (Dorylus sp.; Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Jan BECK & Britta K. KUNZ Abstract Only few documented cases of cooperative self-defence outside the nest are known in social insects. We report ob- servations of Pachycondyla analis (LATREILLE, 1802) workers helping each other against attacking epigaeic driver ants (Dorylus sp.) in a West African savannah. The considerably larger P. analis scanned each other's legs and antennae and removed Dorylus clinging to their extremities. In experimentally staged encounters we could reproduce this be- haviour. Key words: Altruism, interspecific interaction, Ivory Coast, social insects. Myrmecol. News 10: 27-28 Dr. Jan Beck (contact author), Department of Environmental Sciences, Institute of Biogeography, University of Basel, St. Johanns-Vorstadt 10, CH-4056 Basel, Switzerland. E-mail: [email protected] Dr. Britta K. Kunz, Department of Animal Ecology and Tropical Biology, Theodor-Boveri-Institute for Biosciences, Am Hubland, University of Würzburg, D-97074 Würzburg, Germany. Introduction Worker ants exhibit a wide range of complex cooperative workers really are conspecific with the single male speci- behaviours. Examples include trophallaxis, which is al- men described by Illiger (e.g., RAIGNIER & VAN BOVEN most ubiquitous in ants, cooperative foraging and food trans- 1955; reviewed in TAYLOR 2006) we refer to these ants as port, and nest construction (HÖLLDOBLER & WILSON 1990). Dorylus sp. throughout this article. They live in extremely While cooperative nest defence is well known (HÖLL- large colonies of up to several million workers (GOT- DOBLER & WILSON 1990), the cooperative "self-defence" WALD 1995). -

Selection and Capture of Prey in the African Ponerine Ant Plectroctena Minor (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

Acta Oecologica 22 (2001) 55−60 © 2001 Éditions scientifiques et médicales Elsevier SAS. All rights reserved S1146609X00011000/FLA Selection and capture of prey in the African ponerine ant Plectroctena minor (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Bertrand Schatza*, Jean-Pierre Suzzonib, Bruno Corbarac, Alain Dejeanb a LECA, FRE-CNRS 2041, université Paul-Sabatier, 118, route de Narbonne, 31062 Toulouse cedex, France b LET, UMR-CNRS 5552, université Paul-Sabatier, 118, route de Narbonne, 31062 Toulouse cedex, France c LAPSCO, UPRESA-CNRS 6024, université Blaise-Pascal, 34, avenue Carnot, 63037 Clermont-Ferrand cedex, France Received 27 January 2000; revised 29 November 2000; accepted 15 December 2000 Abstract – Prey selection by Plectroctena minor workers is two-fold. During cafeteria experiments, the workers always selected millipedes, their essential prey, while alternative prey acceptance varied according to the taxa and the situation. Millipedes were seized by the anterior part of their body, stung, and retrieved by single workers that transported them between their legs. They were rarely snapped at, and never abandoned. When P. minor workers were confronted with alternative prey they behaved like generalist species: prey acceptance was inversely correlated to prey size. This was not the case vis-à-vis millipedes that they selected and captured although larger than compared alternative prey. The semi-specialised diet of P. minor permits the colonies to be easily provisioned by a few foraging workers as millipedes are rarely hunted by other predatory arthropods, while alternative prey abound, resulting in low competition pressure in both cases. Different traits characteristic of an adaptation to hunting millipedes were noted and compared with the capture of alternative prey.