Personal Injury and Wrongful Death

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960S and 1970S by Kathryn B. C

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960s and 1970s by Kathryn B. Cox A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music Musicology: History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor James M. Borders Professor Walter T. Everett Professor Jane Fair Fulcher Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Kathryn B. Cox [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6359-1835 © Kathryn B. Cox 2018 DEDICATION For Charles and Bené S. Cox, whose unwavering faith in me has always shone through, even in the hardest times. The world is a better place because you both are in it. And for Laura Ingram Ellis: as much as I wanted this dissertation to spring forth from my head fully formed, like Athena from Zeus’s forehead, it did not happen that way. It happened one sentence at a time, some more excruciatingly wrought than others, and you were there for every single sentence. So these sentences I have written especially for you, Laura, with my deepest and most profound gratitude. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Although it sometimes felt like a solitary process, I wrote this dissertation with the help and support of several different people, all of whom I deeply appreciate. First and foremost on this list is Prof. Charles Hiroshi Garrett, whom I learned so much from and whose patience and wisdom helped shape this project. I am very grateful to committee members Prof. James Borders, Prof. Walter Everett, Prof. -

Report on the 1975 Survey of Users of the Services of Radio Stations Wwv and Wwvh

'JM ^^ t*.;: .,-.;, .'-ti ^^#' • J* .^: '•^i'-^v'-' '- \ • REFERENCE N B S V U) NBS TECHNICAL NOTE 674 ^''fff AU O* * U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE/National Bureau of Standards Report On The 1975 Survey of Users of the Services of Radio Stations WWY and WWYH /OO ' .6/5753 . no,(o7i . /975, NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards' was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to promote public safety. The Bureau consists of the Institute for Basic Standards, the Institute for Materials Research, the Institute for Applied Technology, the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology, and the Office for Information Programs. THE INSTITUTE FOR BASIC STANDARDS provides the central basis within the United States of a complete and consistent system of physical measurement; coordinates that system with measurement systems of other nations; and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical measurements throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce. The Institute consists of the Office of Measurement Services, the Office of Radiation Measurement and the following Center and divisions: Applied Mathematics — Electricity — Mechanics — Heat — Optical Physics — Center for Radiation Research: Nuclear Sciences; Applied Radiation — Laboratory Astrophysics ° — Cryogenics" — Electromagnetics" — Time and Frequency". -

Record Store Day 2015 Releases Price Record

Record Store Day 2015 Releases Price Record Store Day 2015 Releases Price Record Store Day 2015 Releases Price Record Store Day 2015 Releases Price 7" SINGLES 7" J Dilla : Fuck The Police - Badge Shaped 7" Edition29.99 7" Soko : Ocean Of Tears 6.99 10" The Replacements : Alex Chilton 12.99 7" Adam And The Ants : Kings Of The Wild Frontier / Ant8.99 Music7" Jagaara : In The Dark 6.49 7" The Spaceape Feat Kode9 & The Bug : Ghost Town8.99 / At War10" With Time Roxy- Gold Music Vinyl :Edition Ladytron 14.99 7" Ryan Adams : Come Pick Me Up 10.99 7" Bert Jansch : Needle Of Death EP 9.99 7" Dusty Springfield : What's It Gonna Be / Spooky 11.99 10" Tracey Thorn : Songs From The Falling 7.99 7" A-ha : Take On Me 13.99 7" Jay-Z / Ghostface Killah : U Don't Know / Whip You11.99 With A7" Strap Stealing Sheep / The Voyeurs : Split 7" 7.99 10" The Waterboys : Puck's Blues 8.99 7" Air : Playground Love 12.99 7" Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings : Little Boys With Shiny5.49 Toys7" The Subways : Taking All The Blame 7.49 10" Young Knives : Something Awful 12.99 7" A$ap Rocky : LPFJ2 / Multiply 7.99 7" Tom Jones : Chills & Fever / Breathless 11.99 7" Supergrass : Sofa (Of My Lethargy) 11.99 10" Various : An On-U Sound Journey Through Time & 8.99Space 7" B-Movie : They Forget / Trash & Mystery 6.49 7" Joy Division : Love Will Tear Us Apart / Leaders Of14.99 Men 7" Temples / Fever The Ghost : Split 7" 7.99 12" SINGLES 7" Syd Barrett / R.E.M. -

All Around the World the Global Opportunity for British Music

1 all around around the world all ALL British Music for Global Opportunity The AROUND THE WORLD CONTENTS Foreword by Geoff Taylor 4 Future Trade Agreements: What the British Music Industry Needs The global opportunity for British music 6 Tariffs and Free Movement of Services and Goods 32 Ease of Movement for Musicians and Crews 33 Protection of Intellectual Property 34 How the BPI Supports Exports Enforcement of Copyright Infringement 34 Why Copyright Matters 35 Music Export Growth Scheme 12 BPI Trade Missions 17 British Music Exports: A Worldwide Summary The global music landscape Europe 40 British Music & Global Growth 20 North America 46 Increasing Global Competition 22 Asia 48 British Music Exports 23 South/Central America 52 Record Companies Fuel this Global Success 24 Australasia 54 The Story of Breaking an Artist Globally 28 the future outlook for british music 56 4 5 all around around the world all around the world all The Global Opportunity for British Music for Global Opportunity The BRITISH MUSIC IS GLOBAL, British Music for Global Opportunity The AND SO IS ITS FUTURE FOREWORD BY GEOFF TAYLOR From the British ‘invasion’ of the US in the Sixties to the The global strength of North American music is more recent phenomenal international success of Adele, enhanced by its large population size. With younger Lewis Capaldi and Ed Sheeran, the UK has an almost music fans using streaming platforms as their unrivalled heritage in producing truly global recording THE GLOBAL TOP-SELLING ARTIST principal means of music discovery, the importance stars. We are the world’s leading exporter of music after of algorithmically-programmed playlists on streaming the US – and one of the few net exporters of music in ALBUM HAS COME FROM A BRITISH platforms is growing. -

INDUSTRIOUS REINFORCEMENT Constant Audio Action on Tour with the 1975

Cover Story The 1975 live at Madison Square Garden (MSG) on the recent tour leg. The Adamson arrays are flying left and right. INDUSTRIOUS REINFORCEMENT Constant audio action on tour with The 1975. by Kevin Young, photos by Arnold Brower HE 1975 likes to keep busy. he says, explaining that he took the gig The band, which continues to strongly Even before the release based on Oliver’s past recommendations gain popularity, just concluded a run of of its second full-length and the fact the band was also bringing arena/shed/theatre dates in the U.S. over album, I like it when you on monitor engineer Francois Pare, who’s the course of spring 2017, the seventh T sleep, for you are so beautiful worked with Rigby regularly over the past leg of the current tour, before moving on yet so unaware of it (2016), the Manchester, six years. In turn, Pare requested that to a series of shows in Europe. It was on UK-based band has toured relentlessly, monitor tech Chris Hall join them as well. this leg when Eighth Day Sound, based in notes Jay Rigby, front of house engineer The team on this tour is rounded out by Highland Heights, OH with offices in LA, on the ongoing tour. veteran front of house systems tech Dan London and Sydney, suggested a switch He adds that while he’s based in Los Bluhm and PA tech Jon Dixon. of the main PA system to an Adamson Angeles, he’s rarely been there since sign- Systems Engineering E-Series rig. -

Download the 1975 Album Rar

1 / 2 Download The 1975 Album Rar May 29, 2021 — The 1975 - The 1975 (Deluxe Edition) Torrent Mega zip rar Mediafire 320 kbps. DOWNLOAD: http://tinybit.cc/9de2c188. Download The 1975 .... Oct 23, 2020 · Japanese Music Albums ← [Single] Mili – Phantomcat of Meowloween (2020.10.18)[MP3+Hi-Res FLAC] [Album] ... クリープハイプ – どうにかなる日々 download zip rar mp3 aac m4a flac CreepHyp… ... (1975) flac download .. Download prince discography greatest hits rar zip mega. We offer the widest variety of major and independent JPop, japanese anime, music, movies, and game .... Download File SKTDTBS rar. ... Download j-pop, k-pop, c-pop FLAC albums. ... 20/MP3/RAR) By admin On January 20, 2021 In jpop With No Comments. ... 31 MB 470 - KILLER BEE iggy pop 1975 Iggy Pop & James Williamson Kill City.. The 1975 - She's American download free mp3 flac. ... FLAC RAR album: 1731 mb. Album rating: 3.9. Available format: MP3 ... DOWNLOAD. Related albums: ... Anyway, if you like the albums please support the artist by buying the original CD or vinyl. FREE WWE TED DIBIASE THEME SONG DOWNLOAD. Brinsley .... The Free Hard Music community also provides a free Funk rock, Jazz Fusion music downloads of Lenny White Discography with full MP3 MP3 320 kbit/s album in.. Hiphoplord. Download 2021 Hip hop Songs Mp4, Mp3, Album, Zip, EP, American. MENU ... ALBUM: The 1975 – Notes on a Conditional Form · May 21, 2020 .... Apr 28, 2019 — A World Lit Only by Fire is the seventh studio album by English industrial metal band Godflesh. It was released on 7 October 2014 through .... Zippyshare songs mp3 The 1975 Notes on a Conditional Form Stream Album Download. -

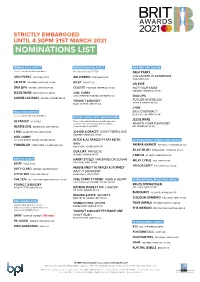

Nominations List

STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 4.30PM 31ST MARCH 2021 NOMINATIONS LIST FEMALE SOLO ARTIST BREAKTHROUGH ARTIST MASTERCARD ALBUM In association with Amazon Music In association with TikTok ARLO PARKS ARLO PARKS TRANSGRESSIVE ARLO PARKS TRANSGRESSIVE COLLAPSED IN SUNBEAMS TRANSGRESSIVE CELESTE POLYDOR, UNIVERSAL MUSIC BICEP NINJA TUNE CELESTE DUA LIPA WARNER, WARNER MUSIC CELESTE POLYDOR, UNIVERSAL MUSIC NOT YOUR MUSE POLYDOR, UNIVERSAL MUSIC JESSIE WARE EMI, UNIVERSAL MUSIC JOEL CORRY ASYLUM/PERFECT HAVOC, WARNER MUSIC DUA LIPA LIANNE LA HAVAS WARNER, WARNER MUSIC YOUNG T & BUGSEY FUTURE NOSTALGIA WARNER, WARNER MUSIC BLACK BUTTER, SONY MUSIC J HUS MALE SOLO ARTIST BIG CONSPIRACY BLACK BUTTER, SONY MUSIC In association with Amazon Music BRITISH SINGLE WITH MASTERCARD JESSIE WARE AJ TRACEY AJ TRACEY The top ten identified by chart eligible sales success then voted for by The Academy, WHAT'S YOUR PLEASURE? HEADIE ONE RELENTLESS, SONY MUSIC Supported by Capital FM EMI, UNIVERSAL MUSIC J HUS BLACK BUTTER, SONY MUSIC 220 KID & GRACEY DON'T NEED LOVE POLYDOR, UNIVERSAL MUSIC JOEL CORRY ASYLUM/PERFECT HAVOC, WARNER MUSIC AITCH & AJ TRACEY FT TAY KEITH INTERNATIONAL FEMALE SOLO ARTIST RAIN YUNGBLUD INTERSCOPE, UNIVERSAL MUSIC ARIANA GRANDE REPUBLIC, UNIVERSAL MUSIC NQ, VIRGIN, UNIVERSAL MUSIC BILLIE EILISH INTERSCOPE, UNIVERSAL MUSIC DUA LIPA PHYSICAL WARNER, WARNER MUSIC CARDI B ATLANTIC, WARNER MUSIC BRITISH GROUP HARRY STYLES WATERMELON SUGAR MILEY CYRUS RCA, SONY MUSIC COLUMBIA, SONY MUSIC BICEP NINJA TUNE TAYLOR SWIFT EMI, UNIVERSAL MUSIC HEADIE -

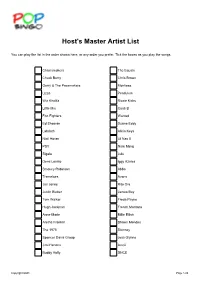

Host's Master Artist List

Host's Master Artist List You can play the list in the order shown here, or any order you prefer. Tick the boxes as you play the songs. Chainsmokers The Equals Chuck Berry Chris Brown Gerry & The Pacemakers Monkees Lizzo Pendulum Wiz Khalifa Rizzle Kicks Little Mix Cardi B Foo Fighters Wanted Ed Sheeran Duane Eddy Labrinth Alicia Keys Niall Horan Lil Nas X PSY Nicki Minaj Sigala Lulu Demi Lovato Iggy Azalea Smokey Robinson Abba Tremeloes Avons Jax Jones Rita Ora Justin Bieber James Bay Tom Walker Freda Payne Hugh Jackman French Montana Anne-Marie Billie Eilish Aretha Franklin Shawn Mendes The 1975 Stormzy Spencer Davis Group Jess Glynne Jimi Hendrix Avicii Buddy Holly DNCE Copyright QOD Page 1/26 Team/Player Sheet 1 Good Luck! Foo Fighters Demi Lovato Jax Jones Monkees Smokey Robinson The Equals Tom Walker Justin Bieber Chainsmokers Jess Glynne Labrinth Pendulum Little Mix Freda Payne Chuck Berry French Montana Sigala Buddy Holly DNCE Rizzle Kicks Copyright QOD Page 2/26 Team/Player Sheet 2 Good Luck! Jax Jones Avons Nicki Minaj Aretha Franklin The 1975 Alicia Keys Wiz Khalifa Rita Ora Pendulum Stormzy Buddy Holly Lil Nas X Lulu Justin Bieber Billie Eilish Duane Eddy Cardi B PSY Jimi Hendrix Sigala Copyright QOD Page 3/26 Team/Player Sheet 3 Good Luck! Rizzle Kicks Little Mix Avons The 1975 Chainsmokers Nicki Minaj Hugh Jackman Wiz Khalifa Buddy Holly Abba Sigala Ed Sheeran Cardi B The Equals Rita Ora James Bay Shawn Mendes Smokey Robinson Anne-Marie Alicia Keys Copyright QOD Page 4/26 Team/Player Sheet 4 Good Luck! Freda Payne The Equals -

Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band Beyoncé Coldplay Guns N

Gross Average Average Total Average Cities Rank Millions Artist Ticket Price Tickets Tickets Gross Shows Agency 1 268.3 Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band 111.48 36,464 2,406,591 4,064,939 66/76 BPB Consulting / Creative Artists Agency 2 256.2 Beyoncé 114.59 48,642 2,237,542 5,573,702 46/49 Creative Artists Agency 3 241.0 Coldplay 90.05 60,828 2,676,425 5,477,701 44/60 Paradigm Talent Agency / X-ray Touring 4 188.4 Guns N’ Roses 111.00 48,490 1,697,164 5,382,317 35/44 United Talent Agency / Int’l Talent Booking 5 167.7 Adele 109.59 34,777 1,530,196 3,811,364 44/107 WME / International Talent Booking 6 163.3 Justin Bieber 92.70 20,484 1,761,642 1,898,837 86/115 Creative Artists Agency 7 110.6 Paul McCartney 127.43 28,924 867,712 3,685,852 30/36 Marshall Arts / MPL Communications 8 97.0 Garth Brooks 69.29 56,000 1,400,000 3,880,000 25/102 WME 9 90.9 The Rolling Stones 122.33 74,343 743,425 9,094,136 10/14 AEG Live 10 85.5 Celine Dion 146.26 30,766 584,560 4,500,000 19/78 ICM Partners / CDA Productions / Solo Agency 11 84.3 Drake 112.08 19,793 752,141 2,218,421 38/56 WME 12 84.1 Luke Bryan 59.00 21,597 1,425,423 1,274,242 66/81 WME 13 82.2 Madonna 216.01 19,033 380,669 4,111,410 20/33 Live Nation Global Touring 14 76.6 Billy Joel 109.67 41,086 698,459 4,505,882 17/28 Artist Group International 15 73.9 Black Sabbath 77.29 14,940 956,139 1,154,688 64/65 CAA / International Talent Booking 16 69.5 Kenny Chesney 76.32 32,512 910,330 2,481,195 28/30 Dale Morris & Associates 17 66.6 Cirque du Soleil - “Toruk - The First Flight” 69.56 21,760 957,446 1,513,636 44/293 Cirque du Soleil 18 65.5 Muse 69.18 24,916 946,805 1,723,684 38/64 United Talent Agency 19 62.9 Iron Maiden 66.00 17,018 953,030 1,123,214 56/59 Creative Artists Agency / K2 Agency 20 61.4 Rihanna 85.63 12,153 717,038 1,040,678 59/64 WME 21 60.1 Maroon 5 68.88 22,373 872,531 1,541,026 39/42 WME / International Talent Booking / CAA 22 58.5 Elton John 110.61 8,530 528,885 943,548 62/92 Howard Rose Agency / Rocket Music Ent. -

15Th May 2015 Pay £5 (Plus £1 Booking

Cambridge Junction’s Fiver – 15 th May 2015 Pay £5 (plus £1 booking fee), watch a load of up-and-coming bands and have a great evening; that’s pretty much what the Fiver is. Now a tradition in Cambridge, the city’s teens flock to the pit, aware of the awesome evening that awaits them. Whether it’s the Fiver Fest, the Fiver Acoustic or just the regular one, you’re pretty much guaranteed to be happy with your decision. Diversity is something that the Fiver always provides, and this one was certainly no exception. 6 bands, 6 completely different styles, 6 things that will cover a broad range of styles, there was definitely something for everyone. I got to have a chat with four of the bands, and I found that all of them have something in common; they’re local bands wanting to build a fan base, and the Fiver’s perfect for that. The evening overall I really enjoyed, and it’s certainly something that I’d go to again. All of the bands had a certain flare to what they were doing, but some really stood out and impressed me a lot. It had a really good vibe (I sound weird saying that but it’s true) and the atmosphere in the room was fantastic. I was told that this night was a quiet one, yet the room still buzzed and everyone seemed to have a great time. The first band was Stormdreamer, and something really stuck out to me about them. They were 13 and 14 years old. -

One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and Their Fans

One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and their Fans Annie Lyons TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin December 2020 __________________________________________ Renita Coleman Department of Journalism Supervising Professor __________________________________________ Hannah Lewis Department of Musicology Second Reader 2 ABSTRACT Author: Annie Lyons Title: One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and their Fans Supervising Professors: Renita Coleman, Ph.D. Hannah Lewis, Ph.D. Boy bands have long been disparaged in music journalism settings, largely in part to their close association with hordes of screaming teenage and prepubescent girls. As rock journalism evolved in the 1960s and 1970s, so did two dismissive and misogynistic stereotypes about female fans: groupies and teenyboppers (Coates, 2003). While groupies were scorned in rock circles for their perceived hypersexuality, teenyboppers, who we can consider an umbrella term including boy band fanbases, were defined by a lack of sexuality and viewed as shallow, immature and prone to hysteria, and ridiculed as hall markers of bad taste, despite being driving forces in commercial markets (Ewens, 2020; Sherman, 2020). Similarly, boy bands have been disdained for their perceived femininity and viewed as inauthentic compared to “real” artists— namely, hypermasculine male rock artists. While the boy band genre has evolved and experienced different eras, depictions of both the bands and their fans have stagnated in media, relying on these old stereotypes (Duffett, 2012). This paper aimed to investigate to what extent modern boy bands are portrayed differently from non-boy bands in music journalism through a quantitative content analysis coding articles for certain tropes and themes. -

Hundreds of Country Artists Have Graced the New Faces Stage. Some

314 performers, new face book 39 years, 1 stage undreds of country artists have graced the New Faces stage. Some of them twice. An accounting of every one sounds like an enormous Requests Htask...until you actually do it and realize the word “enormous” doesn’t quite measure up. 3 friend requests Still, the Country Aircheck team dug in and tracked down as many as possible. We asked a few for their memories of the experience. For others, we were barely able to find biographical information. And we skipped the from his home in Nashville. for Nestea, Miller Beer, Pizza Hut and “The New Faces Show had Union 76, among others. details on artists who are still active. (If you need us to explain George Strait, all those radio people, and for instance, you’re probably reading the wrong publication.) Enjoy. I made a lot of friends. I do Jeanne Pruett: Alabama native Pruett remember they had me use enjoyed a solid string of hits from the early the staff band, and I was ’70s right into the ’80s including the No. resides in Nashville, still tours and will suffering some anxiety over not being able 1 smash, “Satin Sheets.” Pruett is based receive a star in the Hollywood Walk of to use my band.” outside of Nashville and is still active as a 1970 Fame in October, 2009. performer and as a member of the Grand Jack Barlow: He charted with Ole Opry. hits like “Baby, Ain’t That Love” Bobby Harden: Starting out with his two 1972 and “Birmingham Blues,” but by sisters as the pop-singing Harden Trio, Connie Eaton: The Nashville native started Mel Street: West Virginian Street racked the mid-’70s Barlow had become the nationally Harden cracked the country Top 50 back her country career as a teenager and hit the up a long string of hits throughout the ’70s, famous voice of Big Red chewing gum.