Mexico in Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anarchist Movements in Tampico & the Huaste

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Peripheries of Power, Centers of Resistance: Anarchist Movements in Tampico & the Huasteca Region, 1910-1945 A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Latin American Studies (History) by Kevan Antonio Aguilar Committee in Charge: Professor Christine Hunefeldt, Co-Chair Professor Michael Monteon, Co-Chair Professor Max Parra Professor Eric Van Young 2014 The Thesis of Kevan Antonio Aguilar is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii DEDICATION: For my grandfather, Teodoro Aguilar, who taught me to love history and to remember where I came from. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………..…………..…iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………………...…iv Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………….v List of Figures………………………………………………………………………….…vi Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………vii Abstract of the Thesis…………………………………………………………………….xi Introduction……………………………………………………………………………......1 Chapter 1: Geography & Peripheral Anarchism in the Huasteca Region, 1860-1917…………………………………………………………….10 Chapter 2: Anarchist Responses to Post-Revolutionary State Formations, 1918-1930…………………………………………………………….60 Chapter 3: Crisis & the Networks of Revolution: Regional Shifts towards International Solidarity Movements, 1931-1945………………95 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….......126 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………129 v LIST -

Situacion Actual Del Recurso Agua

Capítulo 7. Situación actual del recurso agua José Luís González Barrios Luc Descroix Jambon Ignacio Sánchez Cohen Introducción Ya desde el siglo XVI se documentaba al agua como el principal factor de los asentamientos humanos en el antiguo territorio de la Comarca Lagunera (Corona, 2005). La importancia de los ríos, arroyos y lagunas fue evidente para los primeros pobladores que asentaron sus comunidades cerca de los cauces y embalses naturales, mucho antes del panorama actual dominado por lagunas secas, canales de riego, extensas tierras de cultivo, presas y ciudades. El agua sigue siendo un recurso muy importante para el desarrollo económico de la Comarca Lagunera, sin embargo, con el paso del tiempo, ese desarrollo ha generado recíprocamente una demanda hídrica cada vez mayor y la derrama económica de las actividades productivas no ha ayudado a ordenar el consumo de este recurso, cuyas reservas aun mal estimadas y poco seguras, parecen disminuir hasta agotarse. La elevada extracción de aguas subterráneas, por ejemplo, se ha mantenido durante los últimos sesenta años, provocando un abatimiento sostenido de casi 1.5 m por año y un deterioro gradual de la calidad del agua. Los escenarios futuros con un consumo hídrico igual, son insostenibles para esta región desértica que requiere urgentemente de un ordenamiento en el uso y manejo del agua. Este capitulo presenta una aproximación del estado que guarda el recurso agua en la Comarca Lagunera y sus principales fuentes de abasto hídrico. La Comarca Lagunera inmersa en la cuenca hidrológica Nazas-Aguanaval La Comarca Lagunera es una importante región económica en el norte centro de México que abarca quince municipios (47,980 km2) de los estados de Coahuila y Durango, donde se generan abundantes bienes y servicios relacionados con la actividad agropecuaria e industrial. -

Socioeconomic Factors to Improve Production and Marketing of the Pecan Nut in the Comarca Lagunera

Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas volume 10 number 3 April 01 - May 15, 2019 Article Socioeconomic factors to improve production and marketing of the pecan nut in the Comarca Lagunera José de Jesús Espinoza Arellano1§ María Gabriela Cervantes Vázquez2 Ignacio Orona Castillo2 Víctor Manuel Molina Morejón1 Liliana Angélica Guerrero Ramos1 Adriana Monserrat Fabela Hernández1 1Faculty of Accounting and Administration-Autonomous University of Coahuila-Torreón Unit. Boulevard Revolution 153 Oriente, Col. Centro, Torreón, Coahuila, Mexico. CP. 27000. 2Faculty of Agriculture and Zootechnics-Juarez University of the State of Durango. Ejido Venecia, Gómez Palacio, Durango, Mexico. CP. 35170. §Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract In the Comarca Lagunera 9 957 ha have been established with pecan walnut, with the region being the third in national importance. The studies of socioeconomic type in walnut in Mexico are mainly descriptive, studies that analyze the relationships between the different variables of the crop that allow making recommendations to boost their growth are required. The objective of this work was to analyze the relationship between various socioeconomic factors such as garden size, training and financing with variables such as yields, price, gross income, infrastructure for harvesting and sale of selected nuts. To obtain the information, a survey was applied during 2014 to a sample of 27 orchards distributed throughout the region. The data were analyzed by Analysis of Variance of a factor to compare the means of the groups: orchards that receive vs those that do not receive training, orchards that receive vs those that do not receive financing; and orchards of up to three hectares vs. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs The Slow Fuse of the Revolutionary Mural: Diego Rivera, Historical Revisionism and Poststructuralism Journal Item How to cite: Carter, Warren (2019). The Slow Fuse of the Revolutionary Mural: Diego Rivera, Historical Revisionism and Poststructuralism. Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis, 94 pp. 39–59. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2019 Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://leidykla.vda.lt/Files/file/Acta_94/Acta_94_Carter.pdf Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk 39 The Slow Fuse of the Revolutionary Mural: Diego Rivera, Historical Revisionism and Poststructuralism1 Warren Carter The Open University United Kingdom [email protected] In this paper I will analyse the links between the revisionist histo- riography of the Mexican Revolution of 1910–20 and the revisionist literatu- re on the Mexican murals produced in the period immediately afterwards, as well as the theoretical arguments that underpin both, before making a call for a “post-revisionist” reading of the art. I will then finish by making a post-revisionist iconographical analysis of Diego Rivera’s History of Mexi- co mural produced between 1929-35 as a counterpoint to revisionist ones that instead read it as government propaganda pure and simple. Keywords: Diego Rivera, Mexican Revolution, Mexican muralism, revi sionism, Marxism, structuralism, poststructuralism. -

Many Faces of Mexico. INSTITUTION Resource Center of the Americas, Minneapolis, MN

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 392 686 ( SO 025 807 AUTHOR Ruiz, Octavio Madigan; And Others TITLE Many Faces of Mexico. INSTITUTION Resource Center of the Americas, Minneapolis, MN. REPORT NO ISBN-0-9617743-6-3 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 358p. AVAILABLE FROM ResourceCenter of The Americas, 317 17th Avenue Southeast, Minneapolis, MN 55414-2077 ($49.95; quantity discount up to 30%). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. .DESCRIPTORS Cross Cultural Studies; Foreign Countries; *Latin American Culture; *Latin American History; *Latin Americans; *Mexicans; *Multicultural Education; Social Studies; United States History; Western Civilization IDENTIFIERS *Mexico ABSTRACT This resource book braids together the cultural, political and economic realities which together shape Mexican history. The guiding question for the book is that of: "What do we need to know about Mexico's past in order to understand its present and future?" To address the question, the interdisciplinary resource book addresses key themes including: (1) land and resources;(2) borders and boundaries;(3) migration;(4) basic needs and economic issues;(5) social organization and political participation; (6) popular culture and belief systems; and (7) perspective. The book is divided into five units with lessons for each unit. Units are: (1) "Mexico: Its Place in The Americas"; (2) "Pre-contact to the Spanish Invasion of 1521";(3) "Colonialism to Indeperience 1521-1810";(4) "Mexican/American War to the Revolution: 1810-1920"; and (5) "Revolutionary Mexico through the Present Day." Numerous handouts are include(' with a number of primary and secondary source materials from books and periodicals. -

Optimum Resource Use in Irrigated Agriculture--Comarca Lagunera, Mexico " (1970)

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1970 Optimum resource use in irrigated agriculture-- Comarca Lagunera, Mexico Donald William Lybecker Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agricultural and Resource Economics Commons, and the Agricultural Economics Commons Recommended Citation Lybecker, Donald William, "Optimum resource use in irrigated agriculture--Comarca Lagunera, Mexico " (1970). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 4248. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/4248 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 70-25,805 LYBECKER, Donald William, 1938- OPTIMUM RESOURCE USE IN IRRIGATED AGRI CULTURE—COMARCA LAGUNERA, MEXICO. Iowa State University, Ph.D., 1970 Economics, agricultural University Microfilms, A XERO\Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan OPTIMUM RESOURCE USE IN IRRIGATED AGRICULTURE-- COMARCA LAGUNERA, MEXICO by Donald William Lybacker A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major Subject: Agricultural Economics Approved : Signature was redacted for privacy. In Charge of Merjor Signature was redacted for privacy. Head of Major Department Signature was redacted for privacy. lyan of graduate College Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1970 il TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 Problem Specification and Research Objectives 2 A Brief History of Comarca Lagunera 4 A Description of Comarca Lagunera 7 Other Relevant Studies 15 CHAPTER II. -

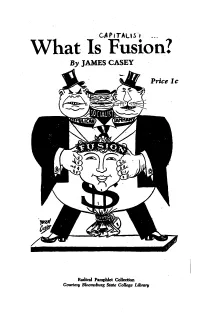

What -Is Fusion? by JAM ES CASEY

CAPiTALIS ' . What -Is Fusion? By JAM ES CASEY 11 -d t Price IIc S. Radical Pampblet Colletion Coutesy Bloomsburg State CoUege Library TRIUMPH AND DISASTER: THE READING SOCIALISTS IN POWER AND DECLINE, 1932-1939-PART II BY KrNNErm E. HENDmcKsoN, JR.' D EFEAT by the fusionists in 1931 did little internal damage to the structure of the Reading socialist movement. As a matter of fact, just the reverse was true. Enthusiasm seemed to intensify and the organization grew.' The party maintained a high profile during this period and was very active in the political and economic affairs of the community, all the while looking forward to the election of 1935 when they would have an op- portunity to regain control of city hall. An examination of these activities, which were conducted for the most part at the branch level, will reveal clearly how the Socialists maintained their organization while they were out of power. In the early 1930s the Reading local was divided into five branches within the city. In the county there were additional branches as well, the number of which increased from four in 1931 to nineteen in 1934. All of these groups brought the rank and file together each week. Party business was conducted, of_ course, but the branch meetings served a broader purpose. Fre- quently, there were lectures and discussions on topics of current interest, along with card parties, dinners, and dances. The basic party unit, therefore, served a very significant social function in the lives of its members, especially important during a period of economic decline when few could afford more than the basic es- sentials of daily life. -

Mexico 1 Mexico

MEXICO MEXICO (1999) Executive summary 1. The Federal Competition Commission (CFC) studied 5551 files in 1999, a figure representing a reduction of 2.8 percent compared to 1998. Of these, 291 cases correspond to mergers and acquisitions, 104 dealt with privatisation processes and concessions or permits for providing public services, 107 comprised anticompetitive practices and inter-state trade restrictions, three are assessments about competition conditions in specific regulated sectors and 50 files concerned competition issues consulted by economic agents to the CFC. The total number of cases concluded in 1999 was 428, a figure 8.74 percent below the one registered during the previous year. 2. Most of the anticompetitive practices investigated and concluded were about horizontal price fixing agreements, refusal to deal, exclusive dealing, boycott and price discrimination or predation. As in previous years, an important amount of mergers notified for review had an international dimension, the two most outstanding involved Monsanto/Cargill and Coca Cola/Cadbury Schweppes. 3. During 1999 the CFC issued several opinions regarding competition aspects of sector specific laws and regulations. Among those reviewed were the Regulations to LP Gas, the Regulations to the Provision of Radio and Television Cable Services; and the Regulations to the Provision of Delivery of Parcel and Document Services. It is also important to mention the CFC participation in the drafting of the federal government proposals for restructuring the electric industry. I. Changes to competition policies, proposed or adopted 4. The Regulations for the Implementation of the Federal Law of Economic Competition and the Internal Regulations of the Federal Competition Commission were issued in 1998. -

Radio, Revolution, and the Mexican State, 1897-1938

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE WIRELESS: RADIO, REVOLUTION, AND THE MEXICAN STATE, 1897-1938 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By JOSEPH JUSTIN CASTRO Norman, Oklahoma 2013 WIRELESS: RADIO, REVOLUTION, AND THE MEXICAN STATE, 1897-1938 A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ______________________________ Dr. Terry Rugeley, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Sterling Evans ______________________________ Dr. James Cane-Carrasco _______________________________ Dr. Alan McPherson _______________________________ Dr. José Juan Colín © Copyright by JOSEPH JUSTIN CASTRO 2013 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements There are a number of people who have aided this project, my development as a professional scholar, and my success at the University of Oklahoma. I owe a huge debt to Dr. Terry Rugeley, my advisor and mentor for the last four and a half years. From my first day at the University of Oklahoma he encouraged me to pursue my own interests and provided key insights into the historian’s craft. He went out of his way to personally introduce me to a number of archives, people, and cities in Mexico. He further acquainted me with other historians in the United States. Most importantly, he gave his time. He never failed to be there when I needed assistance and he always read, critiqued, and returned chapter drafts in a timely manner. Dr. Rugeley and his wife Dr. Margarita Peraza-Rugeley always welcomed me into their home, providing hospitality, sound advice, the occasional side job, and friendship. Thank you both. Other professors at OU helped guide my development as a historian, and their assistance made this dissertation a stronger work. -

El Uso De Las Aguas Subterráneas En El Distrito De Riego 017, Región Lagunera, México

IWMI, Serie Latinoamericana: No. 3 EL USO DE LAS AGUAS SUBTERRÁNEAS EN EL DISTRITO DE RIEGO 017, REGIÓN LAGUNERA, MÉXICO. Alejandro Cruz y Gilbert Levine INSTITUTO INTERNACIONAL DEL MANEJO DEL AGUA IWMI, Serie Latinoamericana: No. 3 EL USO DE AGUAS SUBTERRÁNEAS EN EL DISTRITO DE RIEGO 017, REGIÓN LAGUNERA, MÉXICO IWMI, Serie Latinoamericana: No. 3 El Uso de Aguas Subterráneas en el Distrito de Riego 017, Región Lagunera, México Alejandro Cruz y Gilbert Levine INTERNATIONAL WATER MANAGEMENT INSTITUTE Los autores: Alejandro Cruz es Ingeniero de Campo y Gilbert Levine es Experto Asociado del Programa Nacional IWMI- México. Cruz Alejandro y Gilbert Levine. 1998. El Uso de Aguas Subterráneas en el Distrito de Riego 017, Región Lagunera, México. IWMI, Serie Latinoamericana No. 3. México, D.F, México: Instituto Internacional del Manejo del Agua. IWMI, 1998. Todos los derechos reservados. El Instituto Internacional del Manejo de la Irrigación, uno de los dieciséis centros apoyados por el Grupo Consultivo para la Investigación Agrícola Internacional (GCIAR), fué creado por una Acta del Parlamento de Sri Lanka. El Acta está actualmente siendo revisada para que se lea Instituto Internacional del Manejo del Agua (IWMI, por su sigla en Inglés). Los autores asumen toda la responsabilidad por el contenido de esta publicación. PRESENTACIÓN DE LA SERIE El Instituto Internacional del Manejo del Agua (IWMI, por su sigla en Inglés) fue establecido en el año de 1984 con sede en Colombo, Sri Lanka. El IWMI empezó actividades en Latinoamérica cuando en Mayo de 1990 co- patrocinó con la Comisión Internacional de Riego y Drenaje una sesión especial sobre el Manejo del Agua en Latinoamérica en el marco del Décimo cuarto Congreso Internacional de la Comisión. -

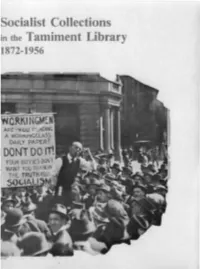

Socialist Collections in the Tamiment Library 1872-1956

Socialist Collections in the Tamiment Library 1872-1956 , '" Pro uesf ---- Start here. ---- This volume is a fmding aid to a ProQuest Research Collection in Microform. To learn more visit: www.proquest.com or call (800) 521-0600 About ProQuest: ProQuest connects people with vetted, reliable information. Key to serious research. the company has forged a 70-year reputation as a gateway to the world's knowledge - from dissertations to governmental and cultural archives to news, in all its forms. Its role is essential to libraries and other organizations whose missions depend on the delivery of complete, trustworthy information. 789 E. E1se~howcr Paik1·1ay • P 0 Box 1346 • Ann Arbor, r.1148106-1346 • USA •Tel: 734.461 4700 • Toll-free 800-521-0600 • wvNJ.proquest.com Socialist Collections in the Tamiment Library 1872-1956 A Guide To The Microfilm Edition Edited by Thomas C. Pardo !NIYfn Microfilming Corporation of America 1.J.J.J A New York Times Company This guide accesses the 68 reels that comprise the microfilm edition of the Socialist Collections in the Tamiment Library, 1872-1956. Information on the availability of this collection and the guide may be obtained by writing: Microfilming Corporation of America 1620 Hawkins Avenue/P.O. Box 10 Sanford, North Carolina 27330 Copyright © 1979, Microfilming Corporation of America ISBN 0-667-00572-2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE v NOTE TO THE RESEARCHER . vii INTRODUCTION . • 1 BRIEF REEL LIST 3 COLLECTION I. SOCIALIST MINUTEBOOKS, 1872-1907 • 5 COLLECTION II. SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY PAPERS, 1900-1905 . • • . • . • • • . 9 COLLECTION III. SOCIALIST LABOR PARTY PAPERS, 1879-1900 13 COLLECTION IV. -

Abstract Where Is Our Revolution?: Workers In

ABSTRACT WHERE IS OUR REVOLUTION?: WORKERS IN CIUDAD JUAREZ AND PARRAL-SANTA BARBARA DURING THE 1930s Andres Hijar, PhD Department of History Northern Illinois University, 2015 Rosemary Feurer, Director This dissertation explores the way workers on the border in Ciudad Juárez and in the mining district of Parral-Santa Barbara increased their power during the 1930s. Unionization, collective bargaining, labor tribunals, political alliances, and direct action gave workers control of crucial aspects of the production process for the first time in the nation’s history. Furthermore, workers’ efforts allowed them to extend their power beyond the workplace and into the community. In some instances, workers were radicalized, especially in the border city. To attenuate workers’ rising power, political and economic elites intervened in labor conflicts in different ways depending on the interests of the elites in the location under study. Political elites’ intervention in some cases deradicalized miners, but it also allowed them to increase their power against The American Smelting and Refinement Company (ASARCO). In Ciudad Juárez, workers’ rising power and radicalization resulted in a violent response from political and economic elites, which eventually reversed workers’ victories during the 1920s and 1930s. The Lázaro Cárdenas presidency supported workers in both the border and the mining district, but failed to rein in political and economic elites’ actions against workers in Juárez, who guarded their interests above those of workers through violence and illegal means. NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DE KALB, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2015 WHERE IS OUR REVOLUTION?: WORKERS IN CIUDAD JUAREZ AND PARRAL-SANTA BARBARA DURING THE 1930s BY ANDRES HIJAR © 2015 Andres Hijar A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Doctoral Director: Rosemary Feurer ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A considerable number of people contributed this to project.