University of Birmingham Style, Character and Revelation in Parry's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parry US 8/5/09 16:32 Page 12

572104bk Parry US 8/5/09 16:32 Page 12 Here God made holy Zion’s name, And did the countenance divine And here he gave them rest. Shine forth upon our clouded hills? Oh, may we ne’er forget what he hath done, And was Jerusalem builded here PARRY Nor prove unmindful of his love, Among these dark satanic mills? That, like the constant sun, On Israel hath shone, Bring me my bow of burning gold! Choral Masterpieces And sent down blessings from above. Bring me my arrows of desire! Bring me my spear! O clouds, unfold! Songs of Farewell C.H. Parry (from Judith) Bring me my chariot of fire! I will not cease from mental fight, @ Jerusalem Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand, Manchester Cathedral Choir And did those feet in ancient time Till we have built Jerusalem Walk upon England’s mountains green? In England’s green and pleasant land. Christopher Stokes And was the Holy Lamb of God On England’s pleasant pastures seen? William Blake (1757-1827) 8.572104 12 572104bk Parry US 8/5/09 16:32 Page 2 Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry (1848–1918) for He is our help and our shield. His grace from above. Songs of Farewell Praise Him who hath taught you He delivered the poor in his affliction, To sing of His love. Sir Hubert Parry came from a family of some which remained dominant. Above all, in London he the fatherless and him that hath none to help him. O praise ye the Lord! distinction. -

(UA) G. Haas, 2. Streichquartett K. Müller, C. Kanajan, T. Hosokawa, J

27.1.2001 G. Haas, U. Chin, S. Newski, L. Lim Ultraschall-Festival, Berlin 8.2.2001 G. Haas Blumenstück (UA) Musik der Jahrhunderte / Eclat Festival, Stuttgart 11.2.2001 G. Haas, 2. Streichquartett Musik der Jahrhunderte / Eclat Festival, Stuttgart 2.6.2001 K. Müller, C. Kanajan, T. Hosokawa, J. Estrada Knut Müller: Thema Landschaft, Leipzig 4.7.2001 G. Kurtág, B. Bartók Musica viva, Göttingen 7.7.2001 S. Reich Parochialkirche, Berlin 22.9.2001 G. Kurtág, B. Bartók, A. Schnabel Akademie der Künste - Berliner Festwochen 28.9.2001 G. Haas, G. Kurtág, S. Newski, M. Osborn (UA) Braunschweig, Städtisches Museum 25./26.10.2001 G. Kurtág, B. Bartók SWR, Kaiserslautern 16.11.2001, 19:30 Uhr J. Estrada, G. Netti (UA),G. F. Haas Tage für Neue Musik Zürich Kleiner Saal Tonhalle 17.12.2001, 20:00 Uhr Fünf Fenster: Kesselhaus, Berlin Zwischen Kontur und Fläche György Kurtág (*1926) Quartetto per archi op.1 [1959] Mark Randall Osborn (*1969) Four Views Coming and Going [2001] Helmut Lachenmann (*1935) Reigen seliger Geister [1989] Gäste: Helmut Lachenmann und Mark Randall Osborn 18.1.2002, 20:00 Uhr Kompositionen von: Sozietätstheater, Dresden Unsuk Chin, Klaus Hinrich Stahmer, Xiaoyong Chen und Conrado del Rosario 4.2.2002, 20:00 Uhr Fünf Fenster: Kesselhaus, Berlin Porträt Georg Friedrich Haas (*1953) Streichquartett Nr. 2 [1998] ...aus freier lust...verbunden... für Trio basso [1994/96] Streichquartett Nr. 1 [1997] mit Eberhard Maldfeld (Kontrabass) Gast: Georg Friedrich Haas 11.3.2002, 20:00 Uhr Fünf Fenster: Kesselhaus, Berlin American Experimental Tradition Morton Feldman (1926-87) Structures [1951] Robert Ashley (1930) In memoriam...Esteban Gomez [1963] Earle Brown (*1926) Streichquartett [1965] John Cage (1912-92) Thirty Pieces [1983] Alvin Lucier (1931) Navigations for strings [1991] Gast: Alvin Lucier 14.4.2002, 20:00 Uhr Georg F. -

The Crucifixion: Stainer's Invention of the Anglican Passion

The Crucifixion: Stainer’s Invention of the Anglican Passion and Its Subsequent Influence on Descendent Works by Maunder, Somervell, Wood, and Thiman Matthew Hoch Abstract The Anglican Passion is a largely forgotten genre that flourished in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Modeled distinctly after the Lutheran Passion— particularly in its use of congregational hymns that punctuate and comment upon the drama—Anglican Passions also owe much to the rise of hymnody and small parish music-making in England during the latter part of the nineteenth century. John Stainer’s The Crucifixion (1887) is a quintessential example of the genre and the Anglican Passion that is most often performed and recorded. This article traces the origins of the genre and explores lesser-known early twentieth-century Anglican Passions that are direct descendants of Stainer’s work. Four works in particular will be reviewed within this historical context: John Henry Maunder’s Olivet to Calvary (1904), Arthur Somervell’s The Passion of Christ (1914), Charles Wood’s The Passion of Our Lord according to St Mark (1920), and Eric Thiman’s The Last Supper (1930). Examining these works in a sequential order reveals a distinct evolution and decline of the genre over the course of these decades, with Wood’s masterpiece standing as the towering achievement of the Anglican Passion genre in the immediate aftermath of World War I. The article concludes with a call for reappraisal of these underperformed works and their potential use in modern liturgical worship. A Brief History of the Passion Genre from the sung in plainchant, and this practice continued Medieval Era to the Eighteenth Century through the late medieval and early Renaissance eras. -

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten Through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Jensen, Joni Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 21:33:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193556 A COMPARISON OF ORIGINS AND INFLUENCES IN THE MUSIC OF VAUGHAN WILLIAMS AND BRITTEN THROUGH ANALYSIS OF THEIR FESTIVAL TE DEUMS by Joni Lynn Jensen Copyright © Joni Lynn Jensen 2005 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC AND DANCE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 5 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Joni Lynn Jensen entitled A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughan Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Bruce Chamberlain _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Elizabeth Schauer _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Josef Knott Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

View/Download Liner Notes

HUBERT PARRY SONGS OF FAREWELL British Choral Music remarkable for its harmonic warmth and melodic simplicity. Gustav Holst (1874-1934) composed The Evening- 1 The Evening-Watch Op.43 No.1 Gustav Holst [4.59] Watch, subtitled ‘Dialogue between the Body Herbert Howells (1892-1983) composed his Soloists: Matthew Long, Clare Wilkinson and the Soul’ in 1924, and conducted its first memorial anthem Take him, earth, for cherishing 2 A Good-Night Richard Rodney Bennett [2.58] performance at the 1925 Three Choirs Festival in late 1963 as a tribute to the assassinated 3 Take him, earth, for cherishing Herbert Howells [9.02] in Gloucester Cathedral. A setting of Henry President John F Kennedy, an event that had moved Vaughan, it was planned as the first of a series him deeply. The text, translated by Helen Waddell, 4 Funeral Ikos John Tavener [7.41] of motets for unaccompanied double chorus, is from a 4th-century poem by Aurelius Clemens Songs of Farewell Hubert Parry but only one other was composed. ‘The Body’ Prudentius. There is a continual suggestion in 5 My soul, there is a country [3.52] is represented by two solo voices, a tenor and the poem of a move or transition from Earth to 6 I know my soul hath power to know all things [2.04] an alto – singing in a metrically free, senza Paradise, and Howells enacts this by the way 7 Never weather-beaten sail [3.22] misura manner – and ‘The Soul’ by the full his music moves from unison melody to very rich 8 There is an old belief [4.52] choir. -

Musikprotokoll-Programmbuch-1990.Pdf

MUSIKPROTOKOLL '90 Zehn Ereignisse im steirischen herbst Raum und Licht Österreichischer Rundfunk ORF-Landesstudio Steiermark INTENDANT: Wolfgang Lorenz 8042 Graz, Marburger Straße 20 Telefon: (0 31 6) 411 80 PROGRAMM: Peter Oswald ORGANISATION: Ingrid Cwienk, Rosalinde Vidic AUFNAHMELEITUNG: Michael Aggermann; Wolfgang Danzmayr, Franz Josef Kerstinger, Heinz Dieter Sibitz TONTECHNISCHE DISPOSITION: Gerhard Kasper, Wolf Hannes Seifried Mit freundlicher Unterstützung der MERKUR YVERBICHERUNGEN 1 Veranstalter und Information: österreichischer Rundfunk Landesstudio Steiermark Abteilung Ernste Musik Marburger Straße 20, A-8042 Graz Telefon (0 31 6) 41 1 80, Durchwahl 253 Büro im Grazer Congreß: Eingang Albrechtgasse 3, 2. Stock Telefon: (0 31 6) 80 49-0 Impressum: ~edieninhaber und Herausgeber: Osterreichischer Rundfunk (ORF), Landesstudio Steiermark Für den Inhalt verantwortlich: Peter Oswald Redaktion: Peter Oswald, Heinz Dieter Sibitz Umschlagentwurf und Layout: Karl Markus Maier Druck: Styria, Graz Kartenverkauf: Zentralkartenbüro Graz, Herrengasse 7 (Passage), 801 OGraz Telefon: (0 31 6) 83 02 55 Eintrittspreise: von S 50.- bis S 120.- Abonnement für alle zehn Konzerte: S 350.- Studenten, Schüler, Arbeitslose: 50% Ermäßigung Preis des Programmbuches: S 50.- 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis ZEITTAFEL ...................................................................... Seite 4 Komponisten, Werke, Interpreten, Aufführungsdauer und Ausstrahlung im ORF ZUM THEMA ................................................................... Seite 10 RAUMKLANG - -

Katalog 2013

KATALOG 2013 S PRO NOVA O T PRO NOVA Der vorliegende Katalog enthält alle lieferbaren Werke nach dem Stand vom 1. Januar 2013. Mit dem Erscheinen dieses Katalogs verlieren alle früheren Kataloge ihre Gültigkeit. The present catalogue contains all available works up to January 1, 2013. On publication of this catalogue all prior catalogues will be invalid. Ce présent catalogue concerne toutes les œuvres disponibles à la date du 1er Janvier 2013. Ce catalogue annule et remplace ceux précédemment établis. Edition PRO NOVA Sonoton Music GmbH & Co. KG Schleibingerstr. 10 D-81669 München Germany Tel.: 089 / 44 77 82-0 Fax: 089 / 44 77 82-88 e-mail: [email protected] Auslieferung / Distribution: Verlag Neue Musik GmbH Grabbealle 15 D-13156 Berlin Germany Tel.: 030 / 61 69 81 0 Fax: 030 / 61 69 81 21 e-mail: [email protected] Die Preise sind in € angegeben. Preisänderungen und Irrtum bleiben vorbehalten. The prices are quoted in €. Prices are subject to change. Errors reserved. Les prix sont indiqués en €. Les prix peuvent être modifiés à tout moment et sont donnés sauf erreur. ♦ Inhalt ♦ Contents ♦ Table des matières ♦ ♦ Legende ♦ Legend ♦ Légend ............................................................................................................2 ♦ Abkürzungen & Übersetzungen ♦ Abbreviations & Translation ♦ Abréviations & Traduction .......2 ♦ Werke nach Komponisten ♦ Works listed by composer Classifi cation des œuvres par compositeur .......................................................................................5 ♦ Werke -

UC Santa Barbara Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara English Reception of Felix Mendelssohn as Told Through British Music Histories A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Linda Joann Shaver-Gleason Committee in charge: Professor Derek Katz, Chair Professor David Paul Professor Stefanie Tcharos September 2016 The dissertation of Linda Joann Shaver-Gleason is approved. ____________________________________________ David Paul ____________________________________________ Stefanie Tcharos ____________________________________________ Derek Katz, Committee Chair September 2016 English Reception of Felix Mendelssohn as Told Through British Music Histories Copyright © 2016 by Linda Joann Shaver-Gleason iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I must first acknowledge my own mortality. During the course of writing this dissertation, I was diagnosed with stage IV breast cancer which had spread to my spine. I spent weeks in the hospital and months afterward mostly bedridden. So, I owe a debt of gratitude to oncologists Juliet Penn and James Waisman for finding a chemotherapy that fights my tumors while keeping the side effects manageable enough for me to work. A warm thank you to the folks at the Solvang Cancer Center who take care of me during chemo sessions, and thank you also to the people at Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital, Santa Ynez Valley Cottage Hospital, Lompoc Valley Medical Center, City of Hope, and Sansum Clinic Lompoc. Without them, I would not be around to thank anyone else. Thank you to my family who helped out during this difficult time, particularly my parents, Carl and Patricia Shaver; my sister-in-law, Andrea Langham; and my niece, Daisy Langham. Thank you also to Ellen and Rich Krasin, Ruth and Steve Marotti, Shirley Shaver, Mary Lou Trocke, Jim and Cindy Gleason, and Ralph Lincoln. -

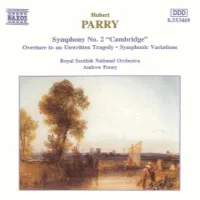

Symphony No. 2 "Cambridge" Overture to an Unwritten Tragedy Symphonic Variations

Hubert PARRY Symphony No. 2 "Cambridge" Overture to an Unwritten Tragedy Symphonic Variations Royal Scottish National Orchestra Andrew Penny Charles Hubert Parry (1848 - 1918) Overture to an Unwritten Tragedy Symphony No. 2 in F major, 'The Cambridge' Symphonic Variations in E majorlminor Sir Hubert Parry came from a family of some distinction. He was the second son, and third surviving child of Thomas Gambier Parry by his first wife. His father's maternal great-uncle was Lord Gambier, Admiral of the Fleet, whose name he had taken, while Thomas Parry himself inherited a fortune from his own father, a director in the East India Company. Hubert Parry was educated at Eton, where he was able to distinguish himself in music, not so much in the desultory musical atmosphere that then obtained at the College, but through association with George Elvey at St George's Chapel, Windsor, and from Elvey he was at least able to have sound enough technical instruction and compose music for the choir. While at school he took the Oxford Bachelor of Music degree, the requirements of which, it must be said, have changed considerably since Parry's time. At Oxford he made the most of the musical opportunities offered, continuing, as at school, to compose music, particularly songs and sacred music and to enjoy informal musical gatherings, although his university studies were in law and history. During this period he was able to study, in a long vacation, with Henry Hugo Pierson in Stuttgart. Parry enjoyed an association with the Herbert family, notably with his school-friend George Herbert, 13th Earl of Pembroke. -

The Stainer Memorial in St. Paul's Cathedral Author(S): F

The Stainer Memorial in St. Paul's Cathedral Author(s): F. G. E. Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 45, No. 731 (Jan. 1, 1904), pp. 26-28 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/903295 Accessed: 27-06-2016 09:14 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times This content downloaded from 128.197.26.12 on Mon, 27 Jun 2016 09:14:36 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms 26 THE MUSICAL TIMES.-JANUARY I, 1904. In an interesting article in Le Courrier Musical, THE STAINER MEMORIAL November 15, 1903, entitled ' De quelques ameliora- tions souhaitables pour le d6veloppement de lart IN ST. PAUL'S CATHEDRAL. musical en France,' signed M.-D. Calvocoressi, occurs The spirit of John Stainer seemed to hover the following:- round the little company gathered together in When in Spain three years ago, I heard M. Pedrell's St. Paul's Cathedral on the morning of the 16th of 'Los Pireneos,' a manifestation of national art cal- last month. -

Newsletter- Broader Sense It Encompasses Review and Recognized Authority in Bailey, Derek

Vol. 1 Nos. 1-2 Published for the CIMA by the Music Research Institute, Richmond CA USA October 1999 Intercultural Musicology The Bulletin of the Centre for Intercultural Music Arts, London, U.K. CIMA Council of Management Steven Stanton, Chair compositions in which elements of Akin Euba, Director Robert Kwami, Deputy Director non-Western traditional music are Lucy Duran Editorial Note combined with those of Western Maxine Franklin Susan Jackson art music require a scholarly Cynthia Tse Kimberlin approach which integrates John Mayer The aim of Intercultural Musicology techniques of ethnomusicology with Richard Nzerem Malcolm Troup is to provide a forum for discourse that those of historical musicology. Mike Wright includes the development of a theoretical framework for the nascent The editors are particularly International Advisory Council field of intercultural musciology. interested in materials dealing with Charles Camilleri (Malta) S. A. K. Durga (India) interculturalism after 1950 and Samha El-Kholy (Egypt) This field includes the study of (a) welcome contributions that generate Cynthia Tse Kimberlin (USA) one’s own indigenous music culture Fernando Maglia (Argentina) discourse on the concept of Sun Xing-Qun (China) using techniques applicable to other intercultural musicology (e.g., Valerie Ross (Malaysia) music cultures (b) music cultures Klaus Hinrich Stahmer (Germany) research reports, previews and Justinian Tamusuza (Uganda) other than one’s indigenous culture (c) reviews of performances, notes on Mike Wright (U.K.) music created by combining elements the works of composers and from various cultures, and (d) other performers, biographical data on Co-Editors forms of intercultural activity, for Cynthia Tse Kimberlin & Akin Euba composers and performers, example, the study of performers who theoretical concepts bearing upon specialize in non-indigenous music creative methods in intercultural idioms. -

Herwig Zack – Made in Germany Page Nos

2289AV-Zack_bklt v5 06/09/2013 14:24 Page 1 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer AVIE YELLOW Catalogue No. 2289 AV BLACK Job Title: Herwig Zack – Made in Germany Page Nos. Herwig Zack on AVIE Records Made in Germany Works for Solo Violin Essentials 4 Strings Only J.S. Bach · Bartók · Kreisler J.S. Bach · Ben-Haim J.S. Bach • Skalkottas · Ysaÿe Berio · Bloch AV2155 AV2189 Hindemith • Stahmer • Reger • Herwig Zack Catoire · Ravel Works for Violin and Piano AV2143 AV2289 2289AV-Zack_bklt v5 06/09/2013 14:24 Page 2 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer AVIE YELLOW Catalogue No. 2289 AV BLACK Job Title: Herwig Zack – Made in Germany Page Nos. Johann Sebastian Bach Sonata / Sonate / Sonate, Op. 31/2 (1685 –1750) £ I. Leicht bewegte Viertel 2:17 Sonata No. 1 · Sonate Nr. 1 · Sonate No 1, BWV 1001 („Es ist so schönes Wetter draußen…“) in G minor · in g-Moll · en Sol mineur $ II. Ruhig bewegte Achtel 3:06 % III. Gemächliche Viertel 1:19 1 I. Adagio 4:20 ^ IV. Fünf Variationen 4:52 2 II. Fuga: Allegro 5:36 über das Lied „Komm lieber Mai“ Slight differences in the sound of the recording of the various pieces are intended and supposed to 3 III. Siciliana 3:50 von Mozart: Leicht bewegt underline the specific character of the particular composition. 4 IV. Presto 3:49 Leichte Unterschiede des Klangbildes bei verschiedenen Werken sind beabsichtigt und sollen den Prelude and Fragment · Präludium und Fragment spezifischen Charakter der jeweiligen Komposition unterstreichen.