Population Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Icd-9-Cm (2010)

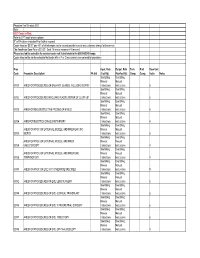

ICD-9-CM (2010) PROCEDURE CODE LONG DESCRIPTION SHORT DESCRIPTION 0001 Therapeutic ultrasound of vessels of head and neck Ther ult head & neck ves 0002 Therapeutic ultrasound of heart Ther ultrasound of heart 0003 Therapeutic ultrasound of peripheral vascular vessels Ther ult peripheral ves 0009 Other therapeutic ultrasound Other therapeutic ultsnd 0010 Implantation of chemotherapeutic agent Implant chemothera agent 0011 Infusion of drotrecogin alfa (activated) Infus drotrecogin alfa 0012 Administration of inhaled nitric oxide Adm inhal nitric oxide 0013 Injection or infusion of nesiritide Inject/infus nesiritide 0014 Injection or infusion of oxazolidinone class of antibiotics Injection oxazolidinone 0015 High-dose infusion interleukin-2 [IL-2] High-dose infusion IL-2 0016 Pressurized treatment of venous bypass graft [conduit] with pharmaceutical substance Pressurized treat graft 0017 Infusion of vasopressor agent Infusion of vasopressor 0018 Infusion of immunosuppressive antibody therapy Infus immunosup antibody 0019 Disruption of blood brain barrier via infusion [BBBD] BBBD via infusion 0021 Intravascular imaging of extracranial cerebral vessels IVUS extracran cereb ves 0022 Intravascular imaging of intrathoracic vessels IVUS intrathoracic ves 0023 Intravascular imaging of peripheral vessels IVUS peripheral vessels 0024 Intravascular imaging of coronary vessels IVUS coronary vessels 0025 Intravascular imaging of renal vessels IVUS renal vessels 0028 Intravascular imaging, other specified vessel(s) Intravascul imaging NEC 0029 Intravascular -

CMH PHYSICIAN PRACTICE PRICING EFFECTIVE FEBRUARY 1, 2018 SERVICE DESCRIPTION PRICE 1 Lung with Ventilation

CMH PHYSICIAN PRACTICE PRICING EFFECTIVE FEBRUARY 1, 2018 SERVICE DESCRIPTION PRICE 1 lung with ventilation; PRO $1,600.00 12 LEAD EKG $0.01 1ST HOSP CARE PR D 30 MIN $201.13 1ST HOSP CARE PR D 50 MIN $271.90 1ST HOSP CARE PR D 70 MIN $402.72 1ST HOSP/BIRTHING CENTER CARE PER DAY NML NB $258.16 1ST HOSP/BIRTHING CENTER NB ADMIT&DSCHG SM DATE $294.25 1ST INPATIENT CRITICAL CARE PR DAY AGE 28 DAYS/< $2,592.55 1ST INPT CONSLTJ 110 MIN $475.01 1ST INPT CONSLTJ 20 MIN $114.73 1ST INPT CONSLTJ 40 MIN $176.70 1ST INPT CONSLTJ 55 MIN $269.62 1ST INPT CONSLTJ 80 MIN $388.96 1ST NF CARE PR D E/M HI SEVERITY $320.35 1ST NF CARE PR D E/M LW SEVERITY $237.44 1ST NF CARE PR D E/M MOD SEVERITY $251.01 1ST OBS CARE PR D HIGH SEVERITY $369.28 1ST OBS CARE PR D LOW SEVERITY $198.80 1ST OBS CARE PR D MODERATE SEVERITY $269.53 1ST PREVENTIVE MEDICINE NEW PATIENT < 1YR $274.17 1ST PREVENTIVE MEDICINE NEW PATIENT AGE 12-17 YR $294.88 1ST PREVENTIVE MEDICINE NEW PATIENT AGE 1-4 YRS $271.93 1ST PREVENTIVE MEDICINE NEW PATIENT AGE 18-39YRS $338.17 1ST PREVENTIVE MEDICINE NEW PATIENT AGE 40-64YRS $379.14 1ST PREVENTIVE MEDICINE NEW PATIENT AGE 5-11 YRS $290.27 1ST PREVENTIVE MEDICINE NEW PATIENT AGE 65YRS&> $76.69 2 OR MORE FALLS WITH INJURY $0.01 7 FIELD PHOTO INTERP DOC REV $0.01 76856 U/S PELVIC COMPL/OFC; PRO $319.25 ABD PARACENTESIS WO IMAGING $219.25 ABDL LMPHADEC REG CELIAC GSTR PORTAL PRIPNCRTC $740.82 ABDOM PARACENTESE WO/IMAGING GUIDANCE $465.49 ABDOMEN ULTRASOUND LTD $215.32 Abdominoperineal resection; PRO $800.00 ABLATION & RCNSTJ ATRIA LMTD $3,868.03 -

Effective March 20, 2001 CPT Codes and Descriptions Only Are Copyright

Effective March 20, 2001 NOTICE The five-digit numeric codes and descriptions included in the Medical Reimbursement Schedule are obtained from the Physicians’ Current Procedural Terminology, copyright 1999 by the American Medical Association (CPT). CPT is a listing of descriptive terms and numeric identifying codes and modifiers for reporting medical services and procedures performed by physicians and other health care providers. This publication includes only CPT numeric identifying codes and modifiers for reporting medical services and procedures that were selected by the Louisiana Department of Labor, Office of Workers’ Compensation. Any use of CPT outside the fee schedule should refer to the Physicians’ Current Procedural Terminology, copyright 1999 American Medical Association and any update thereto. These CPT publications contain the complete and most current listing of CPT descriptive terms and numeric identifying codes and modifiers for reporting medical services and procedures. No fee schedules, basic unit values, relative value guides, conversion factors or scales are included in any part of the Physicians’ Current Procedural Terminology, copyright 1999, by the American Medical Association. All rights reserved. *Copyright 2000 Louisiana Department of Labor, Office of Workers’ compensation ™ Maximum Fee Allowance Schedule Office of Workers' Compensation CPT Global Maximum Code Mod Description Days Allowance ----- ---- ---------------------------- ----- -------- 00100 Integ sys head or saliv glands; nos 5 + TM 00102 Plastic repair -

NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures

NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures 87:2009 Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (NOMESCO) NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP), version 1.14 Organization in charge of NCSP maintenance and updating: Nordic Centre for Classifications in Health Care WHO Collaborating Centre for the Family of International Classifications in the Nordic Countries Norwegian Directorate of Health PO Box 700 St. Olavs plass 0130 Oslo, Norway Phone: +47 24 16 31 50 Fax: +47 24 16 30 16 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.nordclass.org Centre staff responsible for NCSP maintenance and updating: Arnt Ole Ree, Centre Head Glen Thorsen, Trine Fresvig, Expert Advisers on NCSP Nordic Reference Group for Classification Matters: Denmark: Søren Bang, Ole B. Larsen, Solvejg Bang, Danish National Board of Health Finland: Jorma Komulainen, Matti Mäkelä, National Institute for Health and Welfare Iceland: Lilja Sigrun Jonsdottir, Directorate of Health, Statistics Iceland Norway: Øystein Hebnes, Trine Fresvig, Glen Thorsen, KITH, Norwegian Centre for Informatics in Health and Social Care Sweden: Lars Berg, Gunnar Henriksson, Olafr Steinum, Annika Näslund, National Board of Health and Welfare Nordic Centre: Arnt Ole Ree, Lars Age Johansson, Olafr Steinum, Glen Thorsen, Trine Fresvig © Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (NOMESCO) 2009 Islands Brygge 67, DK-2300 Copenhagen Ø Phone: +45 72 22 76 25 Fax: +45 32 95 54 70 E-mail: [email protected] Cover by: Sistersbrandts Designstue, Copenhagen Printed by: AN:sats - Tryk & Design a-s, Copenhagen 2008 ISBN 978-87-89702-69-8 PREFACE Preface to NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures Version 1.14 The Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (NOMESCO) published the first printed edition of the NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP) in 1996. -

Physician Fee Schedule 2021 Note

Physician Fee Schedule 2021 Note: 2021 Codes in Red; Refer to CPT book for descriptions R" in PA column indicates Prior Auth is required Codes listed as '$0.00" pay 45% of billed amount not to exceed provider’s usual and customary charge for the service The Anesthesia Base Rate is $15.20. Each 15 minute increment=1 time unit. Please use lab fee schedule for covered codes not listed below in the 80000-89249 range. Codes listed on the lab fee schedule that begin with a P or Q are currently non-covered for physicians Proc Inpat. Rate Outpat. Rate Tech. Prof. Base Unit Code Procedure Description PA Ind (Facility) (NonFacility) Comp. Comp. Value Notes See Billing See Billing Manual Manual 00100 ANES FOR PROCEDURES ON SALIVARY GLANDS, INCLUDING BIOPSY Instructions Instructions 5 See Billing See Billing Manual Manual 00102 ANES FOR PROCEDURES INVOLVING PLASTIC REPAIR OF CLEFT LIP Instructions Instructions 6 See Billing See Billing Manual Manual 00103 ANES FOR RECONSTRUCTIVE PROCED OF EYELID Instructions Instructions 5 See Billing See Billing Manual Manual 00104 ANES FOR ELECTROCONVULSIVE THERAPY Instructions Instructions 4 See Billing See Billing ANES FOR PROC ON EXTERNAL, MIDDLE, AND INNER EAR ,INC Manual Manual 00120 BIOPSY Instructions Instructions 5 See Billing See Billing ANES FOR PROC ON EXTERNAL, MIDDLE, AND INNER Manual Manual 00124 EAR,OTOSCOPY Instructions Instructions 4 See Billing See Billing ANES FOR PROC ON EXTERNAL, MIDDLE, AND INNER EAR, Manual Manual 00126 TYMPANOTOMY Instructions Instructions 4 See Billing See Billing Manual -

Minilaparoscopy-Assisted Natural Orifice Surgery

SCIENTIFIC PAPER Minilaparoscopy-Assisted Natural Orifice Surgery Daniel A. Tsin, MD, Liliana T. Colombero, MD, Johann Lambeck, MD, Panagiotis Manolas, MD ABSTRACT Key Words: Natural orifice surgery, Minilaparoscopy, Culdolaparoscopy, Culdoscopy. Background and Objectives: New technology has al- lowed us to perform major abdominal and pelvic surgeries with increasingly smaller instruments. The ultimate goal is surgery with no visible scars. Until current technical lim- itations are overcome, minilaparoscopy-assisted natural INTRODUCTION orifice surgery (MANOS) provides a solution. The aim of The field of minimally invasive surgery has evolved tre- this study was to examine our clinical and experimental mendously in recent years; thus, minilaparoscopy has, in experience with MANOS. many cases, replaced conventional laparoscopy. Smaller abdominal ports not only offer cosmetic advantages but Method: Minilaparoscopic abdominal instruments were also have important clinical implications.1 New technolo- used together with a large vaginal port, which was used gies promise to lead us to an era of even less-invasive for insufflation, visual purposes, introduction of operative procedures. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic sur- instruments, and specimen extraction. Minilaparoscopy- gery (NOTES) is a novel concept that involves a port of assisted intraperitoneal transgastric appendectomy was entry through a natural orifice to the peritoneal cavity to done in simulators (Lap trainer with SimuVision, Simulab perform diagnostic and therapeutic surgical interven- Corp., Seattle, WA). tions.2,3 Natural orifice surgery might be superior to lapa- Results: Since 1998, we have used this technique in 100 roscopic surgery in reducing postoperative abdominal cases including ovarian cystectomies, oophorectomies, wall pain, wound infection, hernia formation, and adhe- salpingo-oophorectomies, myomectomies, appendecto- sions.4 Recently, several reports have demonstrated the mies, and cholecystectomies. -

01 SAP Intro 04

Coding and Payment Guide for Anesthesia Services An essential coding, billing, and payment resource for anesthesiology and pain management Introduction Introduction Coding systems and claim forms are the realities of modern the ICD-9-CM diagnosis code when fourth and fifth digits health care. Of the multiple systems and forms available, are available will result in invalid coding. what you use is greatly determined by the setting, the type of insurance, and your practice style. HCPCS Level I (CPT) Codes The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), in This book provides a comprehensive look at the coding and conjunction with the American Medical Association (AMA), reimbursement systems used by anesthesia providers. It is the American Dental Association (ADA), and several other organized topically and numerically, and can be used as a professional groups have developed, adopted, and comprehensive coding and reimbursement resource and as implemented a three-level coding system describing services a quick-lookup resource for coding. rendered to patients. Level I is the CPT coding system. Coding Systems The most commonly used coding system to report The coding systems discussed in this coding and payment professional and outpatient services is CPT, which is guide seek to answer two questions: What was wrong with published annually and copyrighted by the AMA. CPT the patient (i.e., the diagnosis or diagnoses) and what was codes predominantly describe medical services and done to treat the patient (i.e., the procedures or services procedures, and have been adapted to provide a common rendered). billing language that providers and payers can use for payment purposes. -

Rationale of First-Line Endoscopy-Based Fertility Exploration Using Transvaginal Hydrolaparoscopy and Minihysteroscopy

Human Reproduction, Vol.27, No.8 pp. 2247–2253, 2012 Advanced Access publication on June 6, 2012 doi:10.1093/humrep/des192 OPINION Rationale of first-line endoscopy-based fertility exploration using transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy and minihysteroscopy R.L. De Wilde1 and I. Brosens2,* 1Pius-Hospital, Oldenburg, Germany 2Leuven Institute for Fertility and Embryology, Leuven, Belgium Downloaded from *Correspondence address. Catholic University, Leuven, Belgium. E-mail: [email protected] abstract: The transvaginal access for exploration of tubo-ovarian function in women with unexplained infertility has been revived since http://humrep.oxfordjournals.org/ transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy (THL) was introduced in 1998. One prospective double-blind trial and several reviews have validated the diagnostic value of THL in comparison with laparoscopy for the exploration of women with unexplained infertility. A review of the recent literature confirms the efficacy and safety of the technique for first-line endoscopy-based exploration of fertility. The standard policy of 1-year delay for laparoscopic investigation in unexplained infertility is challenged. In older women and particularly in women experienced in fertility awareness methods, THL and minihysteroscopy can be performed after a waiting period of 6–12 months. Key words: female infertility / laparoscopy / endometriosis / adhesions / surgery at Baskent University Library (BASK) on October 9, 2012 Introduction and complications. Fimbrial phimosis and perifimbrial adhesions were more readily detected. Endometriosis and adhesions could be The investigation of the infertile couple by hysterosalpingography and detected on all the surfaces of the ovary, the distal end of the tube, laparoscopy and also the timing of the investigation are currently highly the lateral pelvic wall, the utero-ovarian and uterosacral ligaments debated issues. -

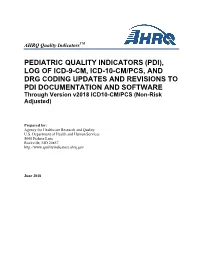

PDI), LOG of ICD-9-CM, ICD-10-CM/PCS, and DRG CODING UPDATES and REVISIONS to PDI DOCUMENTATION and SOFTWARE Through Version V2018 ICD10-CM/PCS (Non-Risk Adjusted

TM AHRQ Quality Indicators PEDIATRIC QUALITY INDICATORS (PDI), LOG OF ICD-9-CM, ICD-10-CM/PCS, AND DRG CODING UPDATES AND REVISIONS TO PDI DOCUMENTATION AND SOFTWARE Through Version v2018 ICD10-CM/PCS (Non-Risk Adjusted) Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov June 2018 TM AHRQ Quality Indicators Pediatric Quality Indicators (PDI), Log of ICD-10-CM/procedure and DRG Coding Updates and Revisions to PDI Documentation and Software Table of Contents 1.0 Log of ICD-09 CM, ICD-10-CM/PC, and MS-DRG Coding Updates and Revisions to PDI Specifications Documentation and Software ..................................................................................... 1 Appendix A - Cardiac Procedure Codes as of February 2009 ......................................................... 90 Appendix B - ICD-9-CM codes for corresponding CCS categories as of September 2010 ............ 91 Appendix C – Miscellaneous Hemorrhage or Hematoma- related Procedure Codes as of December 2012 ................................................................................................................................................. 94 Version v2018 i June 2018 TM AHRQ Quality Indicators Pediatric Quality Indicators (PDI), Log of ICD-10-CM/procedure and DRG Coding Updates and Revisions to PDI Documentation and Software 1.0 Log of ICD-09 CM, ICD-10-CM/PC, and MS-DRG Coding Updates and Revisions to PDI Specifications Documentation and Software The following table summarizes the revisions made to the Pediatric Quality Indicators (PDI) software, software documentation and the technical specification documents in the v2018 ICD-10- CM/PCS version. It also reflects changes to indicator specifications based on updates to ICD-10- CM/PCS codes through Fiscal Year 2018 (effective October 1, 2017) and incorporates coding updates that were implemented in both versions of the PDI software (SAS and WinQI). -

Definitions of Medicare Code Edits

Medicare Code Editor Definitions of Medicare Code Edits v31.0 October 2013 PBL-011 October 2013 Table of Contents About this document .......................................................................................... v Chapter 1: Edit code lists .............................................................................. 7 1. Invalid diagnosis or procedure code ...................................................................................... 7 2. E-code as principal diagnosis ................................................................................................ 7 3. Duplicate of PDX ................................................................................................................... 8 4. Age conflict ............................................................................................................................ 8 Newborn diagnoses ............................................................................................................ 8 Pediatric diagnoses (age 0 through 17) ............................................................................ 13 Maternity diagnoses (age 12 through 55) ......................................................................... 14 Adult diagnoses (age 15 through 124) .............................................................................. 34 5. Sex conflict .......................................................................................................................... 36 Diagnoses for females only .............................................................................................. -

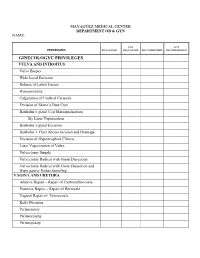

Department Ob & Gyn Name

MAYAGUEZ MEDICAL CENTER DEPARTMENT OB & GYN NAME: NOT NOT PROCEDURES REQUESTED REQUESTED RECOMMENDED RECOMMENDED GINECOLOGYC PRIVILEGES VULVA AND INTROITUS Vulva Biopsy Wide Local Excision Release of Labial Fusion Hymenectomy Fulguration of Urethral Caruncle Excision of Skene’s Duct Cyst Bartholin’s gland Cyst Marsupialization By Laser Vaporization Bartholin’s gland Excision Bartholin’s Duct Abcess Incision and Drainage Excision of Hypertrophied Clitoris Laser Vaporization of Vulva Vulvectomy Simple Vulvectomy Radical with Groin Dissection Vulvectomy Radical with Groin Dissection and Hypo gastric Nodes Sampling VAGINA AND URETHRA Anterior Repair – Repair of Cystourethrocoele Posterior Repair – Repair of Rectocele Vaginal Repair of Enterocoele Kelly Plication Perineotomy Perineorraphy Perineoplasty OB. & GYN Page #2 NOT NOT PROCEDURES REQUESTED REQUESTED RECOMMENDED RECOMMENDED Colpectomy Colpotomy Incision and Drainage of Pelvic Abscess – Vaginal Route Pessary Insertion Removal of Foreign Body from Vagina Exam Under Anesthesia of Vagina in Infants and Children Repair of large Vaginal Lacerations Vesicovaginal Fistula Repair Rectovaginal Fistula Repair Urethrovaginal Fistula Repair Warren Flap Operation for Fourth Degree Tear Sacrospinous Ligament Suspension of Vagina Excision of Transverse Vaginal Septum Correction of Double Barreled Vagina Vaginal Outlet Stenosis Repair McIndoe Vaginoplasty for Neovaginal Plastic Construction of Vagina with Skin Graft William’s Operation for Neovagina Marsupialization of Sub urethral Diverticulum – Spence -

Role of NOTES in the Diagnosis of Women Pelvic Pathologies

World Journal of LaparoscopicPierre C Lucien Surgery, Charley May-August Trevant 2009;2(2):48-52 Role of NOTES in the Diagnosis of Women Pelvic Pathologies Pierre C Lucien Charley Trevant Consultant, Gynecologist, Port-Au-Prince, Haiti Abstract INTRODUCTION Standard diagnostic laparoscopy is considered the gold standard to Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is a common and costly investigate pelvic pathologies (tubal pathology, endometriosis, and adhesions...). It gives a panoramic view of the pelvis. But the condition among women of reproductive age that can lead to invasiveness of diagnostic laparoscopy has almost eliminated its pure infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain. Patients diagnostic role from contemporary management of common pelvic often have lower abdominal pain, fever, an elevated blood C- pathologies. It consequently appears interesting to propose an reactive protein level, and adnexal tenderness, but the clinical endoscopy diagnostic procedure as powerful as the laparoscopy but diagnosis of PID has serious limitations because the symptoms less invasive which doesn’t require general anesthesia and full operative facilities. This is the case of transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy vary in large scale and may be atypical. Gastroenterologic (THL) which proved its efficiency while being as precise as standard problems, urinary tract infections, and other gynecologic diagnosis laparoscopy. problems may simulate PID. Thus, the clinical diagnosis of PID Keywords: Laparoscopy, transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy, NOTES, on the basis of symptoms and signs is often inaccurate. The pelvic pathologies, fertiloscopy, infertility. delay of care increases the risk of long-term complications. Laparoscopy has long been the standard of reference in the diagnosis of PID, but it requires general anesthesia.