Becoming Malala: a Discourse Analysis of Western and Middle Eastern Print and Broadcast Coverage of Malala Yousafzai from 2012-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dear Parent/Guardian Dear Parent

Dear Parent/Guardian To accommodate our studies of The Dressmaker of Khair Khana by Gayle Tzemach Lemmon, I would like to show my students the movie He Named Me Malala. HE NAMED ME MALALA is a portrait of Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Malala Yousafzai, who was targeted by the Taliban and severely wounded by a gunshot when returning home on her school bus in Pakistan’s Swat Valley. The then 15-year-old was singled out, along with her father, for advocating for girls’ education, and the attack on her sparked an outcry from supporters around the world. She miraculously survived and is now a leading campaigner for girls’ education globally as co-founder of the Malala Fund. Documentary filmmaker Davis Guggenheim shows us how Malala, her father Zia and her family are committed to fighting for education for all girls worldwide. The film gives us a glimpse into this extraordinary young girl’s life – from her close relationship with her father who inspired her love for education, to her impassioned speeches at the UN, to her everyday life with her parents and brothers. Thank you in advance, Retha Lee ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Please sign and return this to give permission for your child to watch the movie The Breadwinner in our class. I do give permission for my child, ________________________________, to watch the PG-13 film He Named Me Malala. I do not give permission for my child, ________________________________, to watch PG-13 film He Named Me Malala. Parent Signature: __________________________________________________ Dear Parent/Guardian To accommodate our studies of The Dressmaker of Khair Khana by Gayle Tzemach Lemmon, I would like to show my students the movie He Named Me Malala. -

Celebration and Rescue: Mass Media Portrayals of Malala Yousafzai As Muslim Woman Activist

Celebration and Rescue: Mass Media Portrayals of Malala Yousafzai as Muslim Woman Activist A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Wajeeha Ameen Choudhary in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2016 ii iii Dedication To Allah – my life is a culmination of prayers fulfilled iv Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have possible without the love and support of my parents Shoukat and Zaheera Choudhary, my husband Ahmad Malik, and my siblings Zaheer Choudhary, Aleem Choudhary, and Sumera Ahmad – all of whom weathered the many highs and lows of the thesis process. They are my shoulder to lean on and the first to share in the accomplishments they helped me achieve. My dissertation committee: Dr. Brent Luvaas and Dr. Ernest Hakanen for their continued support and feedback; Dr. Evelyn Alsultany for her direction and enthusiasm from many miles away; and Dr. Alison Novak for her encouragement and friendship. Finally, my advisor and committee chair Dr. Rachel R. Reynolds whose unfailing guidance and faith in my ability shaped me into the scholar I am today. v Table of Contents ABSTRACT ……………………..........................................................................................................vii 1. INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW...………….……………………………………1 1.1 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………...1 1.1.1 Brief Profile of Malala Yousafzai ……….………...…………...………………………………...4 1.2 Literature Review ………………………………………………………………………………….4 1.2.1 Visuality, Reading Visual -

He Named Me Malala

docacademy.org britdoc.org KEY STAGE 3 & 4: HE NAMED ME MALALA UNIT OVERVIEW This six-lesson unit is rooted in exploring the themes and issues portrayed in the He Named Me Malala documentary. The film introduces students to discussions surrounding unity, peace and education in the face of terrorism. These thought-provoking topics help to facilitate discussion among students, introduce them to writer’s purpose, as well as stimulate creative and non-fiction writing. These lessons are designed to help students develop their skills in English across Key Stages Three, Four and Five. SYNOPSIS When 11-year-old blogger Malala Yousafzai education is in crisis, she has continued to focus began detailing her experiences in the Swat on the effort to give all girls 12 years of safe, Valley of Pakistan for the BBC, she had no idea quality and free education. The film He Named what momentous changes were coming in her Me Malala both celebrates her dedication to life. Her father, Ziauddin, a school founder and girls’ education and gives the viewer insight dedicated teacher, was outspoken in his belief into her motivation. It begins with an animated that girls, including his beloved daughter, had portrayal of the teenage folk hero for whom a right to an education. As they continued Malala was named, Malalai of Maiwand, whose to speak out against restrictions imposed by fearlessness and love of country turned the extremists, Ziauddin received constant death tide of battle for Afghan fighters. From those threats, so many that he began to sleep in opening scenes, live action and animation tell different places. -

He Named Me Malala in the Classroom • 7 1

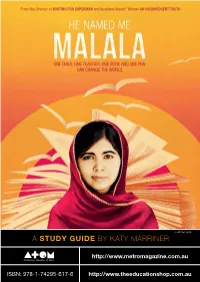

From the Director of WAITING FOR SUPERMAN and Academy Award© Winner AN INCONVENIENT TRUTH © ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-617-6 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Running time: 87 mins CONTENTS: • 3 CURRICULUM LINKS • 4 MALALA YOUSAFZAI • 5 USING HE NAMED ME MALALA IN THE CLASSROOM • 7 1. MALALA YOUSAFZAI • 8 2. MALALAI • 9 3. CONFLICT • 10 4. EDUCATION • 11 5. PEACE • 14 6. ANALYSING A DOCUMENTARY • 14 HE NAMED ME MALALA ONLINE 15 BOOKING HE NAMED ME MALALA AT YOUR CINEMA • 16 IMAGE NATION ABU DHABI • 16 PARKES/MACDONALD PRODUCTIONS He Named Me Malala ‘There is a moment when you have to choose whether to be silent or to stand up.’ – Malala Yousafzai He Named Me Malala is a feature documentary directed by David Guggenheim. The documentary is a portrait of Malala Yousafzai, who was wounded when a Taliban gunman boarded her school bus in Pakistan’s Swat Valley on October 9, 2012 and opened fire. The then fifteen-year-old teenager who had been targeted for speaking out on behalf of girls’ education was shot in the face. No one expected her to survive. The documentary follows the story of her recovery. Now living with her family in Birmingham, England, Malala has emerged as a leading campaigner for the rights of children worldwide and in December 2014 became the youngest-ever Nobel Peace Prize Laureate. Teachers can access the He Named Me Malala trailer at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jtROMdwltJE. THE DOCUMENTARY EXPANDS AND ENRICHES STUDENTS’ UNDERSTANDING OF HUMAN EXPERIENCES AND HIGHLIGHTS HOW INDIVIDUAL ACTIVISM CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE. -

How to Engage Students Through Movies New Partnership Formed by USC Rossier Combines Film- Based Curricula with Professional Development for Teachers

How to engage students through movies New partnership formed by USC Rossier combines film- based curricula with professional development for teachers BY Matthew C. Stevens October 9, 2015 He Named Me Malala follows the life of Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai. (Photo/courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures) Movies are coming to a classroom near you. The USC Rossier School of Education has formed a new partnership with Journeys in Film, an organization that develops film-based curriculum and discussion guides to engage students. The latest guide features He Named Me Malala, a drama that had its West Coast premiere at the Microsoft Theatre on Sept. 29 with 6,500 Los Angeles public school girls in attendance. “It is exactly this kind of synergy we are hoping to generate by using films to inspire and educate today’s students,” said USC Rossier Dean Karen Symms Gallagher, who marveled at the enthusiastic reception of the film by students gathered to kick off Girls Build LA, an initiative of The Los Angeles Fund for Public Education. “Films have the power to change lives, and USC Rossier is excited to partner with Journeys in Film to multiply this same kind of impact many times over.” Founded in 2003 by Joanne Ashe, Journeys in Film hopes to expand its reach through this collaboration with USC Rossier’s Office of Professional Development. As much as this is about film, it’s even more about education. Joanne Ashe “We take feature films and documentaries, both domestic and international, and develop curricula that are aligned with state standards,” said Ashe, executive director of Journeys in Film. -

Video-Windows-Grosse

THEATRICAL VIDEO ANNOUNCEMENT TITLE VIDEO RELEASE VIDEO WINDOW GROSS (in millions) DISTRIBUTOR RELEASE ANNOUNCEMENT WINDOW DISNEY Fantasia/2000 1/1/00 8/24/00 7 mo 23 Days 11/14/00 10 mo 13 Days 60.5 Disney Down to You 1/21/00 5/31/00 4 mo 10 Days 7/11/00 5 mo 20 Days 20.3 Disney Gun Shy 2/4/00 4/11/00 2 mo 7 Days 6/20/00 4 mo 16 Days 1.6 Disney Scream 3 2/4/00 5/13/00 3 mo 9 Days 7/4/00 5 mo 89.1 Disney The Tigger Movie 2/11/00 5/31/00 3 mo 20 Days 8/22/00 6 mo 11 Days 45.5 Disney Reindeer Games 2/25/00 6/2/00 3 mo 8 Days 8/8/00 5 mo 14 Days 23.3 Disney Mission to Mars 3/10/00 7/4/00 3 mo 24 Days 9/12/00 6 mo 2 Days 60.8 Disney High Fidelity 3/31/00 7/4/00 3 mo 4 Days 9/19/00 5 mo 19 Days 27.2 Disney East is East 4/14/00 7/4/00 2 mo 16 Days 9/12/00 4 mo 29 Days 4.1 Disney Keeping the Faith 4/14/00 7/4/00 2 mo 16 Days 10/17/00 6 mo 3 Days 37 Disney Committed 4/28/00 9/7/00 4 mo 10 Days 10/10/00 5 mo 12 Days 0.04 Disney Hamlet 5/12/00 9/18/00 4 mo 6 Days 11/14/00 6 mo 2 Days 1.5 Disney Dinosaur 5/19/00 10/19/00 5 mo 1/30/01 8 mo 11 Days 137.7 Disney Shanghai Noon 5/26/00 8/12/00 2 mo 17 Days 11/14/00 5 mo 19 Days 56.9 Disney Gone in 60 Seconds 6/9/00 9/18/00 3 mo 9 Days 12/12/00 6 mo 3 Days 101.6 Disney Love’s Labour’s Lost 6/9/00 10/19/00 4 mo 10 Days 12/19/00 6 mo 10 Days 0.2 Disney Boys and Girls 6/16/00 9/18/00 3 mo 2 Days 11/14/00 4 mo 29 Days 21.7 Disney Disney’s The Kid 7/7/00 11/28/00 4 mo 21 Days 1/16/01 6 mo 9 Days 69.6 Disney Scary Movie 7/7/00 9/18/00 2 mo 11 Days 1212/00 5 mo 5 Days 157 Disney Coyote Ugly 8/4/00 11/28/00 3 -

Title Author Call Number/Location Library 1964 973.923 US "I Will Never Forget" : Interviews with 39 Former Negro League Players / Kelley, Brent P

Title Author Call Number/Location Library 1964 973.923 US "I will never forget" : interviews with 39 former Negro League players / Kelley, Brent P. 920 K US "Master Harold"-- and the boys / Fugard, Athol, 822 FUG US "They made us many promises" the American Indian experience, 1524 to the present 973.049 THE US "We'll stand by the Union" Robert Gould Shaw and the Black 54th Massachusetts Regiment Burchard, Peter US "When I can read my title clear" : literacy, slavery, and religion in the antebellum South / Cornelius, Janet Duitsman. 305.5 US "Why are all the Black kids sitting together in the cafeteria?" and other conversations about race / Tatum, Beverly Daniel. 305.8 US #NotYourPrincess : voices of Native American women / 971.004 #NO US 100 amazing facts about the Negro / Gates, Henry Louis, 973 GAT US 100 greatest African Americans : a biographical encyclopedia / Asante, Molefi K., 920 A US 100 Hispanic-Americans who changed American history Laezman, Rick j920 LAE MS 1001 things everyone should know about women's history Jones, Constance 305.409 JON US 1607 : a new look at Jamestown / Lange, Karen E. j973 .21 LAN MS 18th century turning points in U.S. history [videorecording] 1736-1750 and 1750-1766 DVD 973.3 EIG 2 US 1919, the year of racial violence : how African Americans fought back / Krugler, David F., 305.800973 KRU US 1920 : the year that made the decade roar / Burns, Eric, 973.91 BUR US 1954 : the year Willie Mays and the first generation of black superstars changed major league baseball forever / Madden, Bill. -

Documentary Film and Media Literacy .Pdf

Consortium for Media Literacy Volume No. 80 March 2016 In This Issue… Theme: Documentary Film and Media Literacy 02 Documentary filmmakers present lifestyles, values, and points of view, and often choose to do so directly. They choose issues to address, and even causes to defend. They often stake a greater claim to truth than other media makers. Research Highlights 04 We discuss the breadth of investigation that characterizes documentary film, and we compare two films on the topic of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church to help audiences understand the differing intentions and techniques of docudrama and documentary. CML News 09 CML, working with Journeys in Film, presented a MediaLit Moment at SxSWedu. Videos of Media Literacy Strategies for Nonprofits are now available online. Media Literacy Resources 10 Find a long list of sources cited and resources for documentary film and media literacy. Med!aLit Moments 12 In this MediaLit Moment, students are introduced to an ancient story of a girl named Malalai that provides insights into the current film He Named Me Malala. This activity was co-created with Journeys in Film. CONNECT!ONS / Med!aLit Moments • March 2016 • 1 Theme: Documentary Film and Media Literacy In the first several minutes of Trouble the Water (2008), Kimberly Roberts uses a Hi8 video recorder to document the hours and days before Hurricane Katrina made landfall in New Orleans, and the first two days of the aftermath. To the untutored eye, Roberts was acting as an empowered citizen journalist, even as the floodwaters continued to encroach on her home and neighborhood in New Orleans’ Ninth Ward. -

Nomination Press Release Award Year: 2016

Nomination Press Release Award Year: 2016 Outstanding Character Voice-Over Performance Family Guy • Pilling Them Softly • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television Seth MacFarlane as Peter Griffin, Stewie Griffin, Brian Griffin, Glenn Quagmire, Dr. Hartman, Tom Tucker, Mr. Spacely South Park • Stunning and Brave • Comedy Central • Central Productions Trey Parker as PC Principal, Cartman South Park • Tweek x Craig • Comedy Central • Central Productions Matt Stone as Craig Tucker, Tweek, Thomas Tucker SuperMansion • Puss in Books • Crackle • Stoopid Buddy Stoodios Keegan-Michael Key as American Ranger, Sgt. Agony SuperMansion • The Inconceivable Escape of Dr. Devizo • Crackle • Stoopid Buddy Stoodios Chris Pine as Dr. Devizo, Robo-Dino Outstanding Animated Program Archer • The Figgis Agency • FX Networks • FX Studios Bob's Burgers • The Horse Rider-er • FOX • Bento Box Entertainment Phineas and Ferb Last Day of Summer • Disney XD • Disney Television Animation The Simpsons • Halloween of Horror • FOX • Gracie Films in association with 20th Century Fox Television South Park • You're Not Yelping • Comedy Central • Central Productions Outstanding Short Form Animated Program Adventure Time • Hall of Egress • Cartoon Network • Cartoon Network Studios The Powerpuff Girls • Once Upon A Townsville • Cartoon Network • Cartoon Network Studios Robot Chicken • Robot Chicken Christmas Special: The X-Mas United • Adult Swim • Stoopid Buddy Stoodios SpongeBob SquarePants • Company Picnic • Nickelodeon • Nickelodeon Steven Universe • The Answer • Cartoon Network -

Downloaded for Free at Malala.Gwu.Edu

I AM MALALA: A TOOLKIT FOR AFTER-SCHOOL CLUBS Adapted from “I Am Malala: A Resource Guide for Educators,” which can be viewed and downloaded for free at malala.gwu.edu. Photo Credits (in order from top to bottom): © Girl Up 2016; HUMAN for Malala Fund / Malin Fezehai; Girl Up / Lameck Luhanga / September 2015 2 |Chapter THEMES 1. Memoir as Literature and History ......................................................................3 2. Education: A Human Right for Girls ...................................................................5 3. Cultural Politics, Gender, and History ................................................................9 4. Religion and Religious Extremism ................................................................. 12 5. Malala and Violence Against Women and Girls ............................................. 15 6. Malala and Women’s Leadership.................................................................... 18 7. Malala and the Media ..................................................................................... 20 8. Global Feminisms: Speaking and Acting about Women and Girls ...................................................................... 23 This toolkit was designed for use by high school/secondary school students in after-school clubs. BEFORE YOU BEGIN The goal of this toolkit is to foster a healthy environment for sharing ideas and experiences, not to put anyone on the spot, or be made to feel exposed or unsafe. Develop ground rules for you and your club. EXAMPLES INCLUDE: 1. Before you -

An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power

AN INCONVENIENT SEQUEL: TRUTH TO POWER Synopsis “After the final no there comes a yes And on that yes the future world depends.” ~Wallace Stevens A decade after AN INCONVENIENT TRUTH brought the climate crisis into the heart of popular culture, comes the riveting and rousing follow-up that shows just how close we are to a real energy revolution. Former Vice President Al Gore continues his tireless fight, traveling around the world training an army of climate champions and influencing international climate policy. Cameras follow him behind the scenes – in moments both private and public, funny and poignant -- as he pursues the inspirational idea that while the stakes have never been higher, the perils of climate change can be overcome with human ingenuity and passion. Paramount Pictures and Participant Media Present an Actual Films Production of AN INCONVENIENT SEQUEL: TRUTH TO POWER directed by Bonni Cohen and Jon Shenk. The producers are Jeff Skoll, Richard Berge and Diane Weyermann and the executive producers are Davis Guggenheim, Lawrence Bender, Laurie David, Scott Z. Burns and Lesley Chilcott. Cinematography is by Jon Shenk, the editors are Don Bernier and Colin Nusbaum and the music is composed by Jeff Beal. AL GORE & THE CLIMATE CRISIS: 10 YEARS LATER “All the beauty of the world is at risk.” -- Al Gore In 2006, when Vice President Al Gore became the focal point of the Oscar®-winning AN INCONVENIENT TRUTH, he was the quintessential man at a crossroads – etching a new path in the wake of the grueling and controversial presidential election of 2000, which ended in an unprecedented Supreme Court decision. -

HE NAMED ME MALALA (A Film by Davis Guggenheim, 88 Minutes) Wednesday, April 13, 2016 7:00 P.M

please post Library Film Series/Muslim Studies Program Annual Conference Community Event Cosponsored by the MSU Libraries Diversity Advisory Committee, MSU Muslim Studies Program, MSU Office for Inclusion and Intercultural Initiatives Project 60/50 HE NAMED ME MALALA (a film by Davis Guggenheim, 88 minutes) Wednesday, April 13, 2016 7:00 p.m. MSU Main Library Green Room Discussion by DR. KHALIDA ZAKI Image courtesy of Imagenation Abu Dhabi FZ He Named Me Malala is an intimate portrait of Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Malala Yousafzai, who was targeted by the Taliban and severely wounded by a gunshot when returning home on her school bus in Pakistan’s Swat Valley. The then 15-year-old was singled out, along with her father, for advocating for girls’ education, and the attack on her sparked an outcry from supporters around the world. She miraculously survived and is now a leading campaigner for girls’ education globally as co-founder of the Malala Fund. lib.msu.edu Acclaimed documentary filmmakerDavis Guggenheim (An Inconvenient Truth, Waiting for Superman) shows us how Malala, her father Zia, and her family are committed to fighting for education for all girls worldwide. The film gives us an inside glimpse into this extraordinary young girl’s For parking information, please visit life—from her close relationship with her father who inspired her love for http://maps.msu.edu/interactive. education, to her impassioned speeches at the UN, to her everyday life The Main Library is wheelchair accessible with her parents and brothers. via the South entrance. Persons with disabilities may request accommodations by calling Lisa Denison at 517.884.6454 one week before an event.