Short Communication NEUROMETRICS DOES NOT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neurodevelopmental Correlates of the Emerging Adult Self T ⁎ Christopher G

Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 36 (2019) 100626 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dcn Neurodevelopmental correlates of the emerging adult self T ⁎ Christopher G. Daveya,b,c, , Alex Fornitod,e, Jesus Pujolf, Michael Breakspearg,h, Lianne Schmaala,b, Ben J. Harrisonc a Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health, Parkville, Australia b Centre for Youth Mental Health, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia c Melbourne Neuropsychiatry Centre, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia d Monash Clinical and Imaging Neuroscience, School of Psychological Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, Australia e Monash Biomedical Imaging, Monash University, Clayton, Australia f MRI Research Unit, Department of Radiology, Hospital del Mar, CIBERSAM G21, Barcelona, Spain g QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Brisbane, Australia h Hunter Medical Research Institute, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, Australia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The self-concept – the set of beliefs that a person has about themselves – shows significant development from Adolescent development adolescence to early adulthood, in parallel with brain development over the same period. We sought to in- Connectivity vestigate how age-related changes in self-appraisal processes corresponded with brain network segregation and Default mode network integration in healthy adolescents and young adults. We scanned 88 participants (46 female), aged from 15 to 25 Functional MRI years, as they performed a self-appraisal task. We first examined their patterns of activation to self-appraisal, and Self replicated prior reports of reduced dorsomedial prefrontal cortex activation with older age, with similar re- ductions in precuneus, right anterior insula/operculum, and a region extending from thalamus to striatum. -

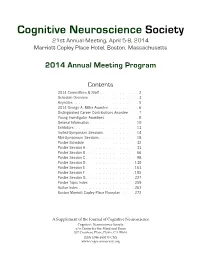

CNS 2014 Program

Cognitive Neuroscience Society 21st Annual Meeting, April 5-8, 2014 Marriott Copley Place Hotel, Boston, Massachusetts 2014 Annual Meeting Program Contents 2014 Committees & Staff . 2 Schedule Overview . 3 . Keynotes . 5 2014 George A . Miller Awardee . 6. Distinguished Career Contributions Awardee . 7 . Young Investigator Awardees . 8 . General Information . 10 Exhibitors . 13 . Invited-Symposium Sessions . 14 Mini-Symposium Sessions . 18 Poster Schedule . 32. Poster Session A . 33 Poster Session B . 66 Poster Session C . 98 Poster Session D . 130 Poster Session E . 163 Poster Session F . 195 . Poster Session G . 227 Poster Topic Index . 259. Author Index . 261 . Boston Marriott Copley Place Floorplan . 272. A Supplement of the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience Cognitive Neuroscience Society c/o Center for the Mind and Brain 267 Cousteau Place, Davis, CA 95616 ISSN 1096-8857 © CNS www.cogneurosociety.org 2014 Committees & Staff Governing Board Mini-Symposium Committee Roberto Cabeza, Ph.D., Duke University David Badre, Ph.D., Brown University (Chair) Marta Kutas, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Adam Aron, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Helen Neville, Ph.D., University of Oregon Lila Davachi, Ph.D., New York University Daniel Schacter, Ph.D., Harvard University Elizabeth Kensinger, Ph.D., Boston College Michael S. Gazzaniga, Ph.D., University of California, Gina Kuperberg, Ph.D., Harvard University Santa Barbara (ex officio) Thad Polk, Ph.D., University of Michigan George R. Mangun, Ph.D., University of California, -

A Resource for Assessing Information Processing in the Developing Brain Using EEG and Eye Tracking

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/092213; this version posted December 7, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. TITLE A Resource for Assessing Information Processing in the Developing Brain Using EEG and Eye Tracking AUTHORS Nicolas Langer*3,1, Erica J. Ho*1,2, Lindsay M. Alexander1, Helen Y. Xu1, Renee K. Jozanovic1, Simon Henin5, Samantha Cohen5, Enitan T. Marcelle4,1, Lucas C. Parra5, Michael P. Milham1,6, Simon P. Kelly5,7 AFFILIATIONS 1. Center for the Developing Brain, Child Mind Institute, New York, NY, USA 2. Department of Psychology, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA 3. Methods of Plasticity Research, Department of Psychology, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland 4. Department of Psychology, University of California, Berkeley, USA 5. Department of Biomedical Engineering, City College of New York, New York, USA 6. Center for Biomedical Imaging and Neuromodulation, Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, Orangeburg, New York, USA 7. School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, University College Dublin, Ireland * These authors contributed equally to this work Corresponding author(s): Nicolas Langer ([email protected]), Michael P. Milham ([email protected]) and Simon P. Kelly ([email protected]) 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/092213; this version posted December 7, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

EEG-Based Mental Workload Neurometric to Evaluate the Impact of Different Traffic and Road Conditions in Real Driving Settings

fnhum-12-00509 December 15, 2018 Time: 15:10 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 18 December 2018 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00509 EEG-Based Mental Workload Neurometric to Evaluate the Impact of Different Traffic and Road Conditions in Real Driving Settings Gianluca Di Flumeri1,2,3*, Gianluca Borghini1,2,3, Pietro Aricò1,2,3, Nicolina Sciaraffa1,2,4, Paola Lanzi5, Simone Pozzi5, Valeria Vignali6, Claudio Lantieri6, Arianna Bichicchi6, Andrea Simone6 and Fabio Babiloni1,3,7 1 BrainSigns srl, Rome, Italy, 2 IRCCS Fondazione Santa Lucia, Neuroelectrical Imaging and BCI Lab, Rome, Italy, 3 Department of Molecular Medicine, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy, 4 Department of Anatomical, Histological, Forensic and Orthopedic Sciences, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy, 5 Deep Blue srl, Rome, Italy, 6 Department of Civil, Chemical, Environmental and Materials Engineering (DICAM), School of Engineering and Architecture, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy, 7 Department of Computer Science, Hangzhou Dianzi University, Hangzhou, China Car driving is considered a very complex activity, consisting of different concomitant Edited by: tasks and subtasks, thus it is crucial to understand the impact of different factors, Muthuraman Muthuraman, University Medical Center of the such as road complexity, traffic, dashboard devices, and external events on the driver’s Johannes Gutenberg University behavior and performance. For this reason, in particular situations the cognitive demand Mainz, Germany experienced by the driver could be very high, inducing an excessive experienced Reviewed by: Edmund Wascher, mental workload and consequently an increasing of error commission probability. In Leibniz-Institut für Arbeitsforschung this regard, it has been demonstrated that human error is the main cause of the an der TU Dortmund (IfADo), 57% of road accidents and a contributing factor in most of them. -

Experimental-Design Specific Changes in Spontaneous EEG And

NEUROSCIENCE RESEARCH ARTICLE V. V. Lazarev et al. / Neuroscience 426 (2020) 50–58 Experimental-design Specific Changes in Spontaneous EEG and During Intermittent Photic Stimulation by High Definition Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation V. V. Lazarev, a* N. Gebodh, b T. Tamborino, a M. Bikson b and E. M. Caparelli-Daquer c,d a Laboratory of Neurobiology and Clinical Neurophysiology, National Institute of Women, Children and Adolescents Health Fernandes Figueira, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil b Department of Biomedical Engineering, The City College of New York of The City University of New York, New York, NY, USA c Laboratory of Electrical Stimulation of the Nervous System, Department of Physiological Sciences and Neurosurgery Unit, Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil d Hospital Universita´rio Gaffre´e e Guinle, Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UniRio), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Abstract—Electroencephalography (EEG) as a biomarker of neuromodulation by High Definition transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (HD-tDCS) offers promise as both techniques are deployable and can be integrated into a single head-gear. The present research addresses experimental design for separating focal EEG effect of HD- tDCS in the ‘4-cathode  1-anode’ (4  1) montage over the left motor area (C3). We assessed change in offline EEG at the homologous central (C3, C4), and occipital (O1, O2) locations. Interhemispheric asymmetry was accessed for background EEG at standard frequency bands; and for the intermittent photic stimulation (IPS). EEG was compared post- vs pre-intervention in three HD-tDCS arms: Active (2 mA), Sham (ramp up/down at the start and end), and No-Stimulation (device was not powered), each intervention lasting 20 min. -

David J. Paulsen, Ph.D Curriculum Vitae Department of Psychiatry University of Pittsburgh 110 Loeffler Bldg Pittsburgh, PA 15232 541.510.1840 [email protected]

David J. Paulsen, Ph.D Curriculum vitae Department of Psychiatry University of Pittsburgh 110 Loeffler Bldg Pittsburgh, PA 15232 541.510.1840 [email protected] Education Ph.D., Psychology & Neuroscience, Duke University, 2012 Dissertation: Development of Decision-Making Under Risk M.S., Psychology, University of Oregon, 2006 Thesis: The Processing of Non-Symbolic Numerical Magnitudes as Indexed by ERPs B.S., Psychology, Philosophy, University of Oregon, 2003 Thesis: The Process of Meaning: James’ Fringe Revisited Academic Employment 2012- University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Laboratory of Neurocognitive Development, Postdoctoral Scholar 2003-2007 University of Oregon, Brain Development Lab, Research Associate 2002-2003 Electrical Geodesics Inc., Brain Electrophysiology Lab, Research Assistant Honors and Awards 2012 T-32 Training Program in the Neurobiology of Substance Use and Abuse, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry 2012 Mortimer D. Sackler Summer Institute for Developmental Neuroscience 2010-2012 F32 National Research Service Award, National Institute on Drug Abuse 2011 Honorarium, Scientific Research Network on Decision Neuroscience & Aging 2011 Vertical Integration Program Summer Fellowship, Duke University 2009 Vertical Integration Program Summer Fellowship, Duke University 2005-2006 Graduate Teaching Fellowship, University of Oregon 2003 Phi Beta Kappa, Honors in Philosophy, Cum Laude 2003 George Rebec Prize for outstanding essay in philosophy 2002 George Rebec Prize for outstanding essay in philosophy Publications September, 2013 David J. Paulsen - CV pg 1 Jones, S.M., Pearson, J., DeWind, N.K., Paulsen, D.J., Tenekedjieva, A., Brannon, E.M. (in press). Lemurs and macaques show similar numerical sensitivity. Animal Cognition. Luna, B., Paulsen, D.J., Padmanabhan, A., Geier, C. -

Investigations in Neuromodulation

Journal of Neurotherapy: Investigations in Neuromodulation, Neurofeedback and Applied Neuroscience Selected Abstracts of Conference Presentations at the 2010 International Society for Neurofeedback and Research (ISNR) 18th Annual Conference, Denver, Colorado Published online: 25 Nov 2010. To cite this article: (2010) Selected Abstracts of Conference Presentations at the 2010 International Society for Neurofeedback and Research (ISNR) 18th Annual Conference, Denver, Colorado, Journal of Neurotherapy: Investigations in Neuromodulation, Neurofeedback and Applied Neuroscience, 14:4, 321-371, DOI: 10.1080/10874208.2010.523353 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10874208.2010.523353 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE © International Society for Neurofeedback and Research (ISNR), all rights reserved. This article (the “Article”) may be accessed online from ISNR at no charge. The Article may be viewed online, stored in electronic or physical form, or archived for research, teaching, and private study purposes. The Article may be archived in public libraries or university libraries at the direction of said public library or university library. Any other reproduction of the Article for redistribution, sale, resale, loan, sublicensing, systematic supply, or other distribution, including both physical and electronic reproduction for such purposes, is expressly forbidden. Preparing or reproducing derivative works of this article is expressly forbidden. ISNR makes no representation or warranty as to the accuracy or completeness of any content in the Article. From 1995 to 2013 the Journal of Neurotherapy was the official publication of ISNR (www. Isnr.org); on April 27, 2016 ISNR acquired the journal from Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. In 2014, ISNR established its official open-access journal NeuroRegulation (ISSN: 2373-0587; www.neuroregulation.org). -

Electroencephalography

13081Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1994;57:1308-1319 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.57.11.1308 on 1 November 1994. Downloaded from NEUROLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS Electroencephalography C D Binnie, P F Prior Genesis ofthe electroencephalogram cific diagnostic significance. Thus slowing The electroencephalogram (EEG) is a record- may arise from causes as diverse as cerebral ing of cerebral electrical potentials by elec- oedema or hypoxia, or systemic disorders trodes on the scalp. Cerebral electrical activity such as hepatic insufficiency. The most reli- includes action potentials that are brief and able abnormal EEG sign is reduction of nor- produce circumscribed electrical fields, and mal activity, ranging from reduced amplitude slower, more widespread, postsynaptic poten- over a past cerebral infarct or a subdural tials. The magnitude of the signal recorded haematoma, to electrocerebral silence in brain from a neural generator depends on the solid death. Spiky waveforms (epileptiform activity) angle subtended at the electrode. Conse- occur in epilepsy and in some patients with quently, the activity of a single neuron can be cerebral disorder but without seizures. recorded by an adjacent microelectrode, but Rhythmic slow activities may occur bilaterally not at a distant scalp electrode. Synchronous over the frontal or posterior temporal regions activity in a horizontal laminar aggregate of in patients with dysfunction of diencephalic or neurons with parallel orientation may, how- brainstem structures. ever, constitute a generator of sufficient extent The EEG is profoundly influenced by alter- to be detectable on the scalp. Thus the EEG ations in vigilance and also changes with age, is a spatiotemporal average of synchronous most noticeably during childhood. -

Exploration of the Pathophysiology of Chronic Pain Using

EEGXXX10.1177/1550059417736444Clinical EEG and NeurosciencePrichep et al 736444research-article2017 Original Article Clinical EEG and Neuroscience 1 –11 Exploration of the Pathophysiology of © EEG and Clinical Neuroscience Society (ECNS) 2017 Reprints and permissions: Chronic Pain Using Quantitative EEG sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1550059417736444 10.1177/1550059417736444 Source Localization journals.sagepub.com/home/eeg Leslie S. Prichep1,2, Jaini Shah3, Henry Merkin4, and Emile M. Hiesiger5 Abstract Chronic pain affects more than 35% of the US adult population representing a major public health imperative. Currently, there are no objective means for identifying the presence of pain, nor for quantifying pain severity. Through a better understanding of the pathophysiology of pain, objective indicators of pain might be forthcoming. Brain mechanisms mediating the painful state were imaged in this study, using source localization of the EEG. In a population of 77 chronic pain patients, significant overactivation of the “Pain Matrix” or pain network, was found in brain regions including, the anterior cingulate, anterior and posterior insula, parietal lobule, thalamus, S1, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), consistent with those reported with conventional functional imaging, and extended to include the mid and posterior cingulate, suggesting that the increased temporal resolution of electrophysiological measures may allow a more precise identification of the pain network. Significant differences between those who self-report high and low pain were reported for some of the regions of interest (ROIs), maximally on left hemisphere in the DLPFC, suggesting encoding of pain intensity occurs in a subset of pain network ROIs. Furthermore, a preliminary multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to select quantitative-EEG features which demonstrated a highly significant predictive relationship of self-reported pain scores. -

Neurophysiological Measures for Human Factors Evaluation in Real World Settings

Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience Neurophysiological Measures for Human Factors Evaluation in Real World Settings Special Issue Editor in Chief: Pietro Aricò Guest Editors: Gianluca Borghini, Lewis Chuang, and Jochen Baumeister Neurophysiological Measures for Human Factors Evaluation in Real World Settings Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience Neurophysiological Measures for Human Factors Evaluation in Real World Settings Special Issue Editor in Chief: Pietro Aricò Guest Editors: Gianluca Borghini, Lewis Chuang, and Jochen Baumeister Copyright © 2019 Hindawi. All rights reserved. This is a special issue published in “Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience.” All articles are open access articles distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Editorial Board Ricardo Aler, Spain Paolo Gastaldo, Italy Gerard McKee, Nigeria Amparo Alonso-Betanzos, Spain S. Ghosh-Dastidar, USA Michele Migliore, Italy Pietro Aricò, Italy Manuel Graña, Spain Paulo Moura Oliveira, Portugal Hasan Ayaz, USA Rodolfo E. Haber, Spain Debajyoti Mukhopadhyay, India Sylvain Baillet, Canada Dominic Heger, Germany Klaus Obermayer, Germany Roman Bartak, Czech Republic Stephen Helms Tillery, USA Karim G. Oweiss, USA Theodore W. Berger, USA J. A. Hernández-Pérez, Mexico Massimo Panella, Italy Daniele Bibbo, Italy Luis Javier Herrera, Spain Fivos Panetsos, Spain Vince D. Calhoun, USA Etienne Hugues, USA David M Powers, Australia Francesco Camastra, Italy Ryotaro Kamimura, Japan Sandhya Samarasinghe, New Zealand Michela Chiappalone, Italy Pasi A. Karjalainen, Finland Saeid Sanei, UK Andrzej Cichocki, Japan Elpida Keravnou, Cyprus Friedhelm Schwenker, Germany Jens Christian Claussen, UK Raşit Köker, Turkey Victor R. L. Shen, Taiwan Silvia Conforto, Italy Dean J. Krusienski, USA Fabio Solari, Italy Justin Dauwels, Singapore Fabio La Foresta, Italy Jussi Tohka, Finland Christian W. -

Changes in Cortical Relative Power in Patients Submitted to a Tendon Transfer

Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2007;65(3-A):628-632 CHANGES IN CORTICAL RELATIVE POWER IN PATIENTS SUBMITTED TO A TENDON TRANSFER A pre and post surgery study Julio Guilherme Silva1,2, Irocy Guedes Knackfuss3, Cláudio Elidio Portella1, Sergio Machado1,2, Bruna Velasques1,2, Victor Hugo do Vale Bastos1,2, Ricardo de Andrade Queiroz2, Marco Antonio Orsini Neves4, Mariana Pacheco2, Camila Ferreira Vorkapic1, Mauricio Cagy1,2, Roberto Piedade1,2, Pedro Ribeiro1,2 ABSTRACT - The aim of this study is analyze possible modifications in the cerebral cortex, through quanti- tative electroencephalography (qEEG) in patients submitted to a tendon transfer procedure (posterior tib- ialis) by the Srinivasan’s technique. Four subjects (2 men and 2 women), 49.25 age average (SD±21.4) were studied. All subjects have been through surgical procedure due to leprosy and had, at least, two years of drop foot condition. The qEEG measured the electrocortical activity (relative power) between 8 and 25 Hz frequencies pre and post surgery. A paired t test analyzed all data (p≤0,05). The results show significant al- terations in the alpha relative power, electrodes F7 (p=0.01) and F8 (p=0.021). Altogether, based on find- ings of the current literature, we can conclude that the tendon transfer procedure suggests electrocortical alterations sensitive to specific qEEG bands. KEY WORDS: qEEG, tendon transfer, relative power, drop foot, leprosy. Alterações na potência relativa cortical em pacientes submetidos a transferência de tendão: es- tudo pré e pós-cirurgico ReSUMO - O objetivo deste estudo é analisar possíveis modificações no córtex cerebral, através da electren- cefalografia quantitativa (EEGq), em pacientes submetidos a um procedimento de transferência de ten- dão (tibial posterior) pela técnica de Srinivasan. -

Kropotov Mueller ERP Fulltext662.Pdf

MAJOR REVIEW ACTAVol. 7, No. 3, 2009, 169-181 NEUROPSYCHOLOGICA Received: 28.09.2009 Accepted: 10.11.2009 WHAT CAN EVENT RELATED A – Study Design POTENTIALS CONTRIBUTE B – Data Collection C – Statistical Analysis D – Data Interpretation TO NEUROPSYCHOLOGY? E – Manuscript Preparation F – Literature Search G – Funds Collection Juri D. Kropotov1,2(A,B,D,E,F), Andreas Mueller3(A,B,D,E,F) 1 Institute of the Human Brain, Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Russia 2 Institute of Psychology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway 3 Praxis für Kind, Organisation und Entwicklung, Brain and Trauma Foundation Chur, Switzerland SUMMARY While psychometrics measures brain functions in terms of behavioral parameters, a recently emerged branch of neu ro science called neurometrics relies on measuring the electrophysiological parameters of brain functioning. There are two approaches in neurometrics. The first relies on the spectral characteristics of spontaneous electroen- cephalograms (EEG) and measures deviations from nor- mality in EEG recorded in the resting state. The second approach relies on event related potentials that measure the electrical responses of the brain to stimuli and actions in behavioral tasks. The present study reviews recent re - search on the application of event related potentials (ERPs) for the discrimination of different types of brain dys - function. Attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is used as an example. It is shown that the diagnostic power of ERPs is enhanced by the recent emergence of new methods of analysis, such as Independent Component Analysis (ICA) and Low Resolution Electromagnetic To - mography (LORETA). Key words: neurometrics, electroencephalography (EEG), Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD This copy is for personal use only - distribution prohibited.