FWU Journal of Social Sciences, Summer 2020, Vol.14, No.2, 1-13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Policing Urban Violence in Pakistan

Policing Urban Violence in Pakistan Asia Report N°255 | 23 January 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Peshawar: The Militant Gateway ..................................................................................... 3 A. Demographics, Geography and Security ................................................................... 3 B. Post-9/11 KPK ............................................................................................................ 5 C. The Taliban and Peshawar ......................................................................................... 6 D. The Sectarian Dimension ........................................................................................... 9 E. Peshawar’s No-Man’s Land ....................................................................................... 11 F. KPK’s Policy Response ............................................................................................... 12 III. Quetta: A Dangerous Junction ........................................................................................ -

Crisis Response Bulletin

IDP IDP IDP CRISIS RESPONSE BULLETIN May 04, 2015 - Volume: 1, Issue: 16 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: English News 3-24 SHC takes notice of non-provision of relief goods in drought-hit areas 03 Modi proposes SAARC team to tackle natural disasters.. As Pakistan's 05 PM commends India's Nepal mission Natural Calamities Section 3-9 Natural Disasters: IDA mulling providing $150 million 05 Safety and Security Section 10-15 Pak-Army teams take on relief works in Peshawar 07 Progress reviewed: Safe City Project to be replicated province-wide 10 Public Services Section 16-24 Ensuring peace across country top priority, says PM 10 Afghan refugees evicted 11 Maps 25-31 PEMRA Bars TV Channels from telecasting hateful speeches 12 Protest: Tribesmen decry unfair treatment by political administration 13 officials Urdu News 41-32 Pakistan to seek extradition of top Baloch insurgents 13 Oil Supply: Government wants to keep PSO-PNSC contract intact 16 Natural Calamities Section 41-38 Workers to take to street for Gas, Electricity 17 Electricity shortfall widens to 4300 mw 18 Safety and Security section 37-35 China playing vital role in overcoming Energy Crisis' 19 Public Service Section 34-32 Use of substandard sunglasses causing eye diseases 23 PAKISTAN WEATHER MAP WIND SPEED MAP OF PAKISTAN MAXIMUM TEMPERATURE MAP OF PAKISTAN VEGETATION ANALYSIS MAP OF PAKISTAN MAPS CNG SECTOR GAS LOAD MANAGEMENT PLAN-SINDH POLIO CASES IN PAKISTAN CANTONMENT BOARD LOCAL BODIES ELECTION MAP 2015 Cantonment Board Local Bodies Election Map 2015 HUNZA NAGAR C GHIZER H ¯ CHITRAL I GILGIT N 80 A 68 DIAMIR 70 UPPER SKARDU UPPER SWAT KOHISTAN DIR LOWER GHANCHE 60 55 KOHISTAN ASTORE SHANGLA 50 BAJAUR LOWER BATAGRAM NEELUM 42 AGENCY DIR TORDHER MANSEHRA 40 MOHMAND BUNER AGENCY MARDAN MUZAFFARABAD 30 HATTIAN CHARSADDA INDIAN 19 ABBOTTABAD BALA PESHAWAR SWABI OCCUPIED KHYBER BAGH 20 NOWSHERA HARIPUR HAVELI KASHMIR AGENCY POONCH 7 KURRAM FR PESHAWAR 6 ORAKZAI SUDHNOTI 10 2 AGENCY FR KOHAT ISLAMABAD 0 AGENCY ATTOCK HANGU KOHAT KOTLI 0 RAWALPINDI MIRPUR FR BANNU KARAK BHIMBER N. -

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan in Pakistan and Militancy Religion a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Project Director Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Robert D. Lamb E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Author Mufti Mariam Mufti June 2012 ISBN 978-0-89206-700-8 CSIS Ë|xHSKITCy067008zv*:+:!:+:! CHARTING our future a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review Project Director Robert L. Lamb Author Mariam Mufti June 2012 CHARTING our future About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed practical solutions to the world’s greatest challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars continue to provide strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and de- velop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Since 1962, CSIS has been dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. After 50 years, CSIS has become one of the world’s pre- eminent international policy institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. -

MEI Report Sunni Deobandi-Shi`I Sectarian Violence in Pakistan Explaining the Resurgence Since 2007 Arif Ra!Q

MEI Report Sunni Deobandi-Shi`i Sectarian Violence in Pakistan Explaining the Resurgence Since 2007 Arif Ra!q Photo Credit: AP Photo/B.K. Bangash December 2014 ! Sunni Deobandi-Shi‘i Sectarian Violence in Pakistan Explaining the Resurgence since 2007 Arif Rafiq! DECEMBER 2014 1 ! ! Contents ! ! I. Summary ................................................................................. 3! II. Acronyms ............................................................................... 5! III. The Author ............................................................................ 8! IV. Introduction .......................................................................... 9! V. Historic Roots of Sunni Deobandi-Shi‘i Conflict in Pakistan ...... 10! VI. Sectarian Violence Surges since 2007: How and Why? ............ 32! VII. Current Trends: Sectarianism Growing .................................. 91! VIII. Policy Recommendations .................................................. 105! IX. Bibliography ..................................................................... 110! X. Notes ................................................................................ 114! ! 2 I. Summary • Sectarian violence between Sunni Deobandi and Shi‘i Muslims in Pakistan has resurged since 2007, resulting in approximately 2,300 deaths in Pakistan’s four main provinces from 2007 to 2013 and an estimated 1,500 deaths in the Kurram Agency from 2007 to 2011. • Baluchistan and Karachi are now the two most active zones of violence between Sunni Deobandis and Shi‘a, -

An Overview of Money Laundering in Pakistan and Worldwide: Causes, Methods, and Socioeconomic Effects

ARTICLES & ESSAYS https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2531-6133/7816 An Overview of Money Laundering in Pakistan and Worldwide: Causes, Methods, and Socioeconomic Effects † WASEEM AHMAD QURESHI TABLE OF CONTENTS: 1. Introduction; 2. Causes, Methods, and Effects of Money Laundering; 2.1. Causes of Money Laundering; 2.1.1. Tax Evasion; 2.1.2. Weak Financial Regulations; 2.1.3. Bribery; 2.1.4. Corruption; 2.1.5. Failure of Banks in Detecting Laundered Money; 2.1.6. Nature of Borders; 2.2. The Three Stages of Money Laundering; 2.2.1. Placement; 2.2.2. Layering; 2.2.3. Integration; 2.3. The Methods of Money Laundering; 2.3.1. Structuring of Money; 2.3.2. Smuggling; 2.3.3. Laundering through Trade; 2.3.4. N.G.Os.; 2.3.5. Round Tripping; 2.3.6. Bank Control; 2.3.7. Cash- Oriented Businesses; 2.3.8. Money Laundering through Real Estate; 2.3.9. Foreign Exchange; 2.4. Effects of Money Laundering; 2.4.1. Economic Impacts; 2.4.2. Social Impacts; 3. Global Magnitude and Combating of Money Laundering; 3.1. Magnitude of the Problem; 3.2. Curbing Money Laundering; 3.2.1. International A.M.L. Organizations; 3.2.1.1. Financial Action Task Force (F.A.T.F.); 3.2.1.2. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 3.2.1.3. FinTRACA; 3.2.2. International A.M.L. Standards; 3.2.2.1. United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances; 3.2.2.2. United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime; 3.2.2.3. -

Page18.Qxd (Page 1)

MONDAY, AUGUST 17, 2015 (PAGE 18) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU Pak Punjab HM assassinated LAHORE, Aug 16: Shaukat Shah was also among those who died in the blast. A minister in Pakistan's The army said that special Punjab province known for his search and rescue team equipped tough anti-Taliban stance was with high-tech machinery to today assassinated by two sui- retrieve the people trapped under cide bombers who blew them- the rubble of the roof which col- selves up at his ancestral home, lapsed due to the bombing. killing at least 15 people in the The banned outfit Lashkar-e- brazen attack. Jhangvi (LeJ) has claimed Shuja Khanzada, 71, the responsibility for the suicide Home Minister of Punjab attack on Khanzada, sources in Province, and a DSP were the interior ministry were quot- BAYOTRA MAHAJAN BIRADARI DEV SATHAN among the 15 people killed ed as saying by Dawn News. when the suicide bombers Police said Khanzada was BISHNAH (J&K) attacked his political office in under threat following the “JAI BALA DEV JI” his native Shadi Khan village in killing of LeJ chief Malik Ishaq “JAI SHEELA DEVI JI” Attock district, rescue and in July. SH NARINDER GUPTA WAS ELECTED AS PRESIDENT OF administration officials said. BAYOTRA MAHAJAN BIRADARI BISHNAH (J&K) ON 9TH OF The intelligence reports say NARINDER GUPTA AUG. 2015. At least 17 people were also 94191-89373 that there are at least 150 sleep- THE FIRST MEETING, WHICH WAS HELD UNDER THE PRESI- injured in the blast. The condi- er cells of LeJ in south Punjab. -

WHITHER PAKISTAN Map Remove.Pmd

WHITHER PAKISTAN? GROWING INSTABILITY AND IMPLICATIONS FOR INDIA Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses New Delhi 1 Whither Pakistan? Growing Instability and Implications for India Cover Illustration : Maps on the cover page show the area under Taliban control in Pakistan and their likely expansion if the Pakistani state fails to take adequate measures to stop the Taliban’s advance, which may lead to the fragmentation of Pakistan. Maps drawn are not to scale. © Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). ISBN: 81-86019-70-7 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this report are of the Task Force and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute and the Government of India. First Published: June 2010 Price : Rs 299/- Published by: Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in Printed at: A.M. Offsetters A-57, Sector-10, Noida-201 301 (U.P.) Tel.: 91-120-4320403 Mob.: 09810888667 E-mail : [email protected] 2 CONTENTS FOREWORD..............................................................................................................................5 LIST OF A BBREVIATIONS.........................................................................................................7 -

Zero Tolerance for Militancy in Punjab

Comprehensive review of NAP Zero tolerance for militancy in Punjab Aoun Sahi Aoun Sahi is an investigative journalist in Islamabad, who has published in leading newspapers including The News. n December 25th, 2014, nine days FATA-based groups fighting security O after Pakistani Taliban attacked forces in tribal areas and adjoining Army Public School in Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. killing 150, mostly children, the country’s political leadership Over years, Punjab became main approved a comprehensive 20-point centre of militant and religious National Action Plan against organizations. On January 14th, 2015, terrorism. Prime Minister Nawaz interior minister Chaudhry Nisar Ali Sharif, in a televised address to the Khan briefed Prime Minister that the nation, described the incident as number of proscribed organisations having “transformed the country.” actively engaged in terrorism and extremism in Punjab province alone, Rare admission had reached 95.3 Beyond the usual vows of countering Punjab-based groups carry the “terrorist mind-set”, Prime signatures on the most deadly and Minister Sharif made a rare audacious plots. Not only did they admission of the presence of militant carry out attacks in key Punjab cities groups in the country’s largest like Lahore and Rawalpindi, Punjab- province Punjab, when he vowed to based groups had key role in go after them, come what may.1A terrorism outside Punjab: They political leader who attended the fought security forces in tribal areas meeting approving NAP recalled and KP, especially in Swat; that one of the topics that dominated orchestrated sectarian attacks against the discussion was militancy in Shia Hazaras in Quetta; attacked Punjab. -

Pakistan. Country Overview — 3

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Country Overview August 2015 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Country Overview August 2015 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00800 numbers or these calls may be billed. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN 978-92-9243-510-3 doi:10.2847/991158 © European Asylum Support Office, 2015 Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. EASO Country of Origin Information Report — Pakistan. Country Overview — 3 Acknowledgments EASO would like to acknowledge the following national asylum and migration departments as the co-authors of this report: Austria, Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum, Country of Origin Information Department Belgium, Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, Cedoca (Centre for Documentation and Research) France, French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless persons (OFPRA), Information, Documentation and Research Division Hungary, Office of Immigration and Nationality, Documentation Centre UK, Home Office, Country Policy and Information Team The following departments reviewed this report: Ireland, Refugee Documentation Centre, Legal Aid Board Lithuania, Migration Department under Ministry of Internal Affairs, Asylum Affairs Division UNHCR has reviewed the report in relation to information for which UNHCR is quoted as the source, relating to persons of concern to UNHCR in Pakistan (refugees, asylum-seekers and stateless persons in Pakistan, as well as IDPs). -

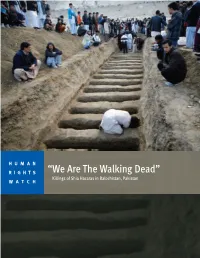

Hazaras in Quetta

HUMAN RIGHTS “We Are The Walking Dead” Killings of Shia Hazaras in Balochistan, Pakistan WATCH “We are the Walking Dead” Killings of Shia Hazaras in Balochistan, Pakistan Copyright © 2014 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-1494 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2014 978-1-62313-1494 “We are the Walking Dead” Killings of Shia Hazara in Balochistan, Pakistan Glossary .............................................................................................................................. i Map of Pakistan ................................................................................................................ iii Map of Balochistan .......................................................................................................... -

Policing Urban Violence in Pakistan

Policing Urban Violence in Pakistan Asia Report N°255 | 23 January 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Peshawar: The Militant Gateway ..................................................................................... 3 A. Demographics, Geography and Security ................................................................... 3 B. Post-9/11 KPK ............................................................................................................ 5 C. The Taliban and Peshawar ......................................................................................... 6 D. The Sectarian Dimension ........................................................................................... 9 E. Peshawar’s No-Man’s Land ....................................................................................... 11 F. KPK’s Policy Response ............................................................................................... 12 III. Quetta: A Dangerous Junction ........................................................................................ -

FFM Bericht Pakistan 2015

The present revised edition of the report - January 2016 - replaces the previous edition published September 2015. For this revised version, parts of chapters 8. – 10.1. have been revised. Please note that the use of the September 2015 edition of the report is no longer authorised. .BFA Bundesamt für Fremdenwesen und Asyl Seite 3 von 76 .BFA Bundesamt für Fremdenwesen und Asyl Seite 4 von 76 Index Summary ............................................................................................................................... 7 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 7 2. Modus Operandi ............................................................................................................. 8 3. General Situation in Pakistan ........................................................................................12 3.1. Karachi ......................................................................................................................13 3.2. Balochistan ................................................................................................................15 3.3. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa .................................................................................................16 3.4. Punjab .......................................................................................................................17 3.5. National Action Plan ..................................................................................................17