Be the Dead Tree on Albert Oehlen's Paintings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martha Jungwirth Albert Oehlen Opening

Galerie Mezzanin Karin Handlbauer 63, rue des Maraîchers CH -∂205 Geneva T + 4∂ 22 328 38 02 [email protected] www.galeriemezzanin.com Martha Jungwirth Albert Oehlen Opening: 23.03.2017 Exhibition: 24.03.-13.05.2017 -- This exhibition is a project between Martha Jungwirth and Albert Oehlen. As I know Albert now quite for a long time, I asked him if he wants to do an exhibition with Martha Jungwirth. Aware that he honours Martha’s work a lot. Albert Oehlen was choosing the works of Martha what you see in the exhibition. Karin Handlbauer Martha Jungwirth was born in 1940 in Vienna, Austria, she lives and works in Vienna. She had solo exhibitions at Secession, Vienna, Austria (with Franz Ringel, 1972) ; Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts, Vienna, Austria (1976) ; documenta 6, Fridericianum, Kassel, Germany, (1977) ; Künstlerhaus Klagenfurt, Austria (1982) ; Museum der Moderne – Rupertinum, Salzburg, Austria (1991) ; Kulturhaus der Stadt Graz, Austria (1999) ; Malfluchten, Museum Moderner Kunst – Stiftung Wörlen, Passau, Germany (1999) ; Künstlerhaus Klagenfurt, Austria (2000) ; Kunsthaus Mürz, Mürzzuschlag, Austria (2008) ; Stadtmuseum Bruneck, Italy (2011) and Kunsthalle Krems, Austria (2014). Jungwirth’s work belongs to known private and institutional collections in US and Europe such as Rubell Family Collection (USA) ; The Barnes Foundation (Philadelphia, USA) ; Albertina (Vienna, Austria) ; Mumok (Vienna, Austria) ; Joanneum (Graz, Austria) ; Lentos (Linz, Austria) ; Rupertinum (Salzburg, Austria) ; Collection City of Vienna (Austria) ; Essl Collection (Klosterneuburg, Austria) ; Museum Angerlehner (Wels, Austria) ; Sammlung Liaunig (Vienna / Neuhaus) ; Sammlung Wemhöner (Berlin / Herfort) ; Sammlung Dichand (Vienna). Albert Oehlen was born in 1954 in Krefeld, Germany and currently lives and works in Switzerland. -

For Immediate Release 14 October 2011

For Immediate Release 14 October 2011 Contacts: Cristiano de Lorenzo +44 (0) 20 7389 2283 [email protected] Matthew Paton +44 (0) 20 7389 2965 [email protected] CHRISTIE’S EVENING AUCTIONS OF POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART AND THE ITALIAN SALE TOTAL £55.6 MILLION / $87.6 MILLION / €63.4 MILLION London - The evening auctions of Post-War & Contemporary Art Auction and The Italian Sale realised a combined total of £55,630,000 / $87,672,880 / €63,473,83, the second highest total for an October sale in London. The top price of the evening was paid for Gerhard Richter‟s seminal Kerze (Candle) painted in 1982, which after a fierce bidding battle was sold for £10,457,250 / $16,480,626 / €11,931,722, a world record price for the artist at auction. In total 10 lots for over £1 million and 20 lots for over $1 million. 9 artist records were set. The corresponding auctions in October 2010 realised a combined total of £38.2 million / $61.2 million / €43.4 million, with 6 lots selling for over £1 million and 18 for over $1 million. POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART This evening‟s Post-War and Contemporary Art Evening Auction realized a total of £38,070,350 / $59,998,872 / €43,438,269 against a pre-sale estimate in the region of £30 million, selling 92% by value and 89% by lot. Buyer breakdown (by lot) was 49% Europe including the UK, 38% Americas and 13% Asia. 7 lots sold for over £1 million / 12 for over $1 million. -

Martin Kippenberger, 43, Artist of Irreverence and Mixed Styles

THE NEW YORK TIMES OBITUARIES 11.3.1997 Martin Kippenberger, 43, Artist Of Irreverence and Mixed Styles By ROBERTA SMITH Martin Kippenberger, widely regarded as one of the most talented German artists of his generation, died on Friday at the University of Vienna Hospital. He was 43 and had moved to Vienna last year. The cause was cancer, said Gisela Capitain, his agent and dealer. A dandyish, articulate, prodigiously prolific artist who loved controversy and confrontation and combined irreverence with a passion for art, Mr. Kippenberger worked at various points in performance art, painting, drawing, sculpture, installation art and photography and also made several musical recordings. He was a ringleader of a younger generation of „bad boy" German artists born mostly after World War II that emerged in the wake of the German Neo-Expressionists. His fellow travelers included Markus and Albert Oehlen, Georg Herold and Günter Förg, and they sometimes seemed almost as well known for their carousing as for their work. Mr. Kippenberger once made a sculpture titled „Street Lamp for Drunks"; its post curved woozily back and forth. In New York City, Mr, Kippenberger was known for a well-received show of improvisational sculptures at Metro Pictures in SoHo in 1987. The pieces incorporated an extensive range of found objects and materials and sundry conceptual premises. He considered no style or artist's work off-limits for appropriation, though his paintings most frequently resembled heavily worked, seemingly defaced fusions of Dadaism, Pop and Neo-Expressionism and often poked fun at the art world or himself. His penchant for mixing media, styles and processes influenced younger artists on both sides of the Atlantic. -

Albert Oehlen

Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin | Paris | London ALBERT OEHLEN Spiegelbilder (1982 – 1990) London: 41 Dover Street, 26 September – 16 November 2019 Galerie Max Hetzler, London is delighted to announce the exhibition Albert Oehlen: Spiegelbilder. Bringing together singular paintings from a significant early series in Albert Oehlen’s oeuvre, this will be the first exhibition dedicated to the Spiegelbilder (‘Mirror Paintings’) in the UK. The exhibition coincides with a major solo show of the artist’s work at the Serpentine Gallery, London, which opens on 2 October 2019. Spanning eight years, from 1982 – 1990, the Spiegelbilder series straddles a decisive period for the artist, during which he moved from the crude figuration and “bad painting” of the late 1970s and early 80s, towards non- objective painting in the late 1980s. Through the Spiegelbilder, Oehlen cemented his reputation for subverting painting conventions. “This mirror idea allowed me to make an ‘original’ invention, but one that is bearable because it is so hackneyed.” –– Albert Oehlen One of Oehlen’s earliest bodies of work, the Spiegelbilder are distinguished by actual pieces of mirror collaged onto the surface of the canvas, highlighting the artist’s unconventional approach to painting from the outset. Although visually distinct, there is an attitude and approach in these paintings towards colour, light, scale and line that carries through later series. Belonging to the Spiegelbilder are some of Oehlen’s first self-portraits, a primary example of which will also be exhibited. Many of the works in the series depict domestic interiors and politically-charged exteriors in a palette of muted colours. -

Martin Kippenberger Self-Portraits at Christie's London on October 11 & 12

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON | 19 SEPTEMBER 2012 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AN IMPORTANT COLLECTION OF MARTIN KIPPENBERGER SELF-PORTRAITS AT CHRISTIE'S LONDON ON OCTOBER 11 & 12 Martin Kippenberger (1953-1997) Untitled (from the series Hand-Painted Pictures) oil on canvas / 71 x 59in. (180.4 x 149.8cm.) / Painted in 1992 Estimate: £2,500,000-3,500,000 London - In an unprecedented event, Christie’s Post-War & Contemporary Art Department will offer on October 11 and 12 an important collection of Martin Kippenberger (1953-1997) self-portraits, including thirteen works on paper and the seminal oil on canvas, Ohne Titel (Untitled), from the series Hand-Painted Pictures) (1992) (estimate: £2,500,000-3,500,000; illustrated above). The latter was previously exhibited in the major retrospectives of the artist’s work held at the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris in 1993, Tate Modern, London in 2006, MoCA, Los Angeles and MoMA, New York in 2009. Assembled over the course of a twenty- five year friendship, this collection belongs to someone who knew the artist so well, that these works offer a unique insight and portrait of the artist. Charismatic and irreverent, Martin Kippenberger is remembered for his conceptual and expressive transformation of the 1980s and 1990s art scene. Francis Outred, Christie's Head of Post-War & Contemporary Art, Europe: “Martin Kippenberger's revolutionary influence on contemporary art practice continues to grow by the day. At the source of his wild approach to and disdain for the preconceived notions of the artist's role in society was his own self. His self- portraits lie at the heart of his oeuvre and I have never seen such an outstanding collection, which so accurately documents his development from the 1970s to his tragic, early death in 1997. -

Exhibition Booklet to the Exhibition Albert Oehlen. Malerei

8. 6.–20. 10. 2013 English museum moderner kunst stiftung ludwig wien Introduction Albert Oehlen is not only one of the most infl uential but also one of the most controversial painters of our time. Born in 1954 in Krefeld, Germany, he has since the end of the 1970s been a key fi gure in the resurgent discussion about the contemporary relevance of painting. The artist has worked systematically to bring painting into confl ict on several fronts — with its own history, with its clichés and its missed opportunities, and also with the ubiquity of images from the worlds of advertising and pop. Painting may have been declared dead, but Oehlen attempts to give it back its freshness and complexity — not by sweeping under the carpet the attacks it has been subjected to and the controversies surrounding its tradition, but rather by making painting itself the live site where they unfold. His forays into pop culture and advertising, trash and computer aesthetics, as well as into political iconography are methodically brought into the overall context of a crafted and composed image. It is as if Oehlen were continually outwitting painting. Oehlen brings the medium’s internal and external enemies — from the avant-garde to new technologies — into his work, while fi nding devious ways to smuggle in tropes as beauty and virtuosity. The exhibition at mumok shows several groups of the artist’s works, beginning with early works from the 1980s such as the “Mirror Paintings,” collages, and paintings featuring mannequins, as well as two of the so-called “Tree Pictures.” Around 1990, a programmatic turn towards abstraction took place in Oehlen’s practice, evident in the artist’s “post-nonrepresentational” works and the “Computer Paintings.” On Level 3, works from the series “Gray Paintings” are on view, along with “Poster Paintings.” The most recent work in the show is presented on Level 4 — a large-format series made between 2010 and 2012, on view here for the fi rst time, in which Oehlen meshes together actionist painting and collaged elements. -

Tramonto Spaventoso April 22–June 5, 2021 456 North Camden Drive, Beverly Hills

Tramonto Spaventoso April 22–June 5, 2021 456 North Camden Drive, Beverly Hills Albert Oehlen in his studio, Ispaster, Spain, 2020. Artwork © Albert Oehlen. Photo: Esther Freund March , Gagosian is pleased to present Tramonto Spaventoso, an exhibition by Albert Oehlen comprising the second part of his version of the Rothko Chapel in Houston as well as other new paintings. The first part of the project—consisting of four paintings that mirror the imposing scale of the Color Field compositions in the Chapel while opposing Rothko’s contemplativeness with their frenetic energy— was exhibited at the Serpentine Galleries, London, in –. Both parts make up the work Tramonto Spaventoso (–). Oehlen uses abstract, figurative, and collaged elements to disrupt the histories and conventions of modern painting. By adding improvised components, he unearths ever-new possibilities for the genre. While championing self-consciously amateurish “bad” painting, Oehlen continues to infuse expressive gesture with Surrealist attitude, openly disparaging the quest for reliable form and stable meaning. In the large-scale canvases on view at the Beverly Hills gallery, Oehlen employs acrylic, spray paint, charcoal, and patterned fabric to interpret and transform John Graham’s painting Tramonto Spaventoso (Terrifying Sunset, –), a work by the Russian-born American modernist painter that he discovered in the s and has been fascinated with ever since. Using Graham’s puzzle-like painting as a vehicle for repeated interpretation, Oehlen reconfigures elements in diverse and absurdist ways across multiple compositions. The exhibition, which goes by the same title, is therefore in part an homage to the earlier, lesser-known artist. Reworking motifs from Graham’s original, including a mermaid and a man sporting a monocle and a Daliesque handlebar moustache, Oehlen improvises on his source. -

Martin Kippenberger

Martin Kippenberger 1953 Born in Dormund, Germany 1972–76 Hamburger Hochschule für Bildende Kunst 1997 Passed away SOLO EXHIBITIONS (selected) 2019 Martin Kippenberger, Bundeskunsthalle Bonn, Bonn, Germany 2018 MOMAS – Museum of Modern Art Syros, Palermo, Istituto Svizzero di Roma, Italy at Fondazione Sant’Elia, Palermo, Italy; MAMCO, Geneva, Italy [Cat.] Body Check. Martin Kippenberger. Maria Lassnig, Museion Foundation. Museum of modern and contemporary art Bozen, Italy; Lenbachhaus, Munich, Germany [Cat.] 2017 Hand Painted Pictures, Skarstedt, New York, CA, USA [Cat.] Buying is Fun, Paying Hurts, Bergamin&Gominde, São Paulo, Brazil 2016 Martin Kippenberger, Bank Austria Wien, Vienna, Austria [Cat.] Das, mit dem alles anfing. Der, mit dem alles anfing, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany 2015 Martin Kippenberger, Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, Japan [Cat.] 2014 ‚Du kommst auch noch in Mode’ – Plakate von Martin Kippenberger, Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany [Cat.] Window Shopping, Capitain Petzel, Berlin, Germany [Cat.] The Raft of Medusa, Skarstedt, New York, CA, USA [Cat.] 2013 Sehr gut; Very Good, Hamburger Bahnhof, Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin, Germany [Cat.] 2011 Kippenberger miró a Picasso, Museo Picasso Málaga, Málaga, Spain [Cat.] 2008 The Problem Perspective, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA [Cat.] 2006 Martin Kippenberger, Tate Modern, London, UK; K 21, Düsseldorf, Germany [Cat.] 2004 Kippenberger: Pinturas, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain -

Daniel Richter

GALERIE THADDAEUS ROPAC DANIEL RICHTER SPAGOTZEN SALZBURG VILLA KAST 24 Saturday - 28 Saturday Parallel to Daniel Richter's solo exhibition in the Salzburg Rupertinum Museum of Modern Art, presenting works created in connection with Daniel Richter's stage-set for Vera Nemirova's production of Alban Berg's Lulu, the Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, in its first collaboration with Richter, is showing his latest series of works. Under the title Spagotzen, a neologism coined by the artist, the exhibition comprises fifteen works showing mysterious figures bathed in an artificial light typical of Richter, against a sometimes seismographically linear background. They seem like actors on a stage, engaged in strange kinds of interaction. Richter's new block of works is distinguished on the one hand by an innovative, graphic, almost secessionist style, the paint applied like varnish, and on the other by a novel orientation towards the world of symbolism at the turn of last century, the mysticism of Odilon Redon and Félix Vallotton's compositions dominated by flat areas of black and white contrasts. "Ultimately, there is no difference between abstract and figurative painting – apart from particular forms of their decipherability. But the problems of organising paint on surface always remain essentially the same. In both cases, it is the same method that makes its way through various forms." Thus Daniel Richter commented in 2004 on his change from abstract to representational painting – a personal turn-round which he carried out at the turn of the century. Born in 1962, the artist has shaped painting in Germany since the 1990s as few others have done. -

Download Jana Schröder Press Packet

JANA SCHRÖDER [email protected] WWW.MIERGALLERY.COM 7277 SANTA MONICA BOULEVARD LOS ANGELES, CA, 90042 T: 323-498-5957 Jana Schröder’s art-making practice seeks to question the validity of traditional painting gestures. Her work is a meditation on process and repetition, refusing the need to derive or represent intellectual meaning solely for the sake of being meaningful. She achieves this by creating an interaction of overlapping colors and layers of paint that create meaning not only on the basis of the gestures that created them, but also through their references to everyday acts of handwriting and scribbling. She uses oil paints to slowly transition initials, signatures and abbreviations onto a large-scale canvas, and by doing so, she manages to isolate and highlight their sheer form. In other paintings, the indelible pencil, with its absurd chemical nature (it irrevocably fades when exposed to sunlight), serves as the perfect platform for expressing gestures freely and as a finalizing act. Jana Schröder (b. 1983, Brilon, Germany; lives and works in Düsseldorf) studied at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf under Professor Albert Oehlen. She has been included in numerous solo and group exhibitions at wellknown institutions, such as the Kunstmuseum Bonn, Germany; Kunstverein Heppenheim, Germany; T293, Rome; Natalia Hug, Cologne; Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich and the Yves Klein Archives, Paris. SELECTED WORKS Jana Schröder Kadlites L20, 2019 Acrylic, graphite and lead on canvas 94 1/2 x 78 3/4 in, 240 x 200 cm Jana Schröder Specshift L1, 2020 Acrylic and oil on canvas 94 1/2 x 78 3/4 in, 240 x 200 cm Jana Schröder PR2, 2017 Copying pencil and oil on paper 79 x 59 in, 200 x 150 cm Jana Schröder Spontacts DL13, 2015 Copying pencil and oil on canvas 78.7 x 61 in, 200 x 155 cm Jana Schröder Spontacts Ö12, 2014 Oil on canvas 70.9 x 59 in, 180 x 150 cm Jana Schröder Kadlites L5, 2018 Acrylic, graphite and lead on canvas 94 1/2 x 78 3/4 in, 240 x 200 cm (JSR19.008) INSTALLATION VIEWS Installation View of Jana Schröder Kadlites (March 16–April 27, 2019). -

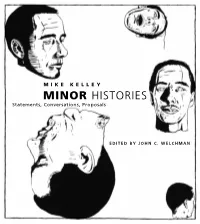

MINOR HISTORIES Statements, Conversations, Proposals MIKE KELLEY Edited by John C

KELLEY MINOR HISTORIES Statements, Conversations, Proposals MIKE KELLEY edited by John C. Welchman What John C. Welchman calls the “blazing network of focused conflations” from which Mike Kelley’s styles are generated is on display in all its diversity in this second volume of his writings. The first volume, Foul Perfection, contained thematic essays and writings about other artists; this collection concentrates on Kelley’s own work, ranging from texts in “voices” that grew out of scripts for performance pieces to expository critical and autobiographical writings. Minor Histories organizes Kelley’s writings into five sections. “Statements” consists of twenty pieces produced MINOR between 1984 and 2002 (most of which were written to accompany exhibitions), including “Ajax,” which draws on MIKE KELLEY Homeric epic, Colgate-Palmolive advertising, and Longinus to present its eponymous hero; “Some Aesthetic High Points,” an exercise in autobiography that counters the standard artist bio included in catalogs and press releases; and a sequence of “creative writings” that use mass cultural tropes in concert with high art mannerisms—approximating in prose the visu- MINOR HISTORIES al styles that characterize Kelley’s artwork. “Video Statements and Proposals” are introductions to videos made by Kelley and other artists, including Paul McCarthy and Bob Flanagan and Sheree Rose. “Image-Texts” offers writings that accom- Statements, Conversations, Proposals pany or are part of artworks and installations. This section includes “A Stopgap Measure,” Kelley’s zestful millennial essay in social satire, and “Meet John Doe,” a collage of appropriated texts. The section “Architecture” features a discussion of Kelley’s Educational Complex (1995) and an interview in which he reflects on the role of architecture in his work. -

The Kippenberger Conundrum: How the Wildly Prolific Artist’S Artist Became an Eight-Figure Auction Darling

The Kippenberger Conundrum: How the Wildly Prolific Artist’s Artist Became an Eight-Figure Auction Darling BY Nate Freeman POSTED 01/08/18 12:40 PM Martin Kippenberger. COURTESY TASCHEN It was the peak of the 2014 fall auction season in New York, and though nearly two decades had gone by since Martin Kippenberger’s death of liver failure in 1997, the artist’s market had never been hotter. Prior to its bellwether postwar and contemporary evening sale, Christie’s had set the estimate for a prized 1988 Kippenberger self-portrait in its November sale at $20 million—an aggressive estimate, but one that paid off. It was bought by dealer Larry Gagosian, hammering at $20 million for a with-premium total of $22.5 million. The sale capped a run of seasons where the Kippenberger market rose precipitously—an irony for an artist who lampooned both “try-hard” artists who sucked up to the market people and the market people who got suckered into buying any of it. All of Kippenberger’s top ten highest-selling works at auction have come in the last five years, and after the one-two punch of 1988 works sold at Christie’s in May and November 2014—the $22.5 million picture nabbed by Gagosian, but also another work from the same series that sold for $18.6 million—the same auction house sold two more Kippenbergers in May 2015: another 1988 self-portrait for $16.4 million, and one of his 1996 paintings of Jacqueline Picasso for $12.5 million. The “Picasso Paintings”—or, as they’re sometimes called, the “Underwear Paintings”—are perhaps Kippenberger’s most beloved series, based on photographs taken of Picasso, his hero, but self-effacing in tone.