Consumers' Perceptions of Voluntary and Involuntary Deconsumption: an Exploratory Sequential Scale Development Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culture Jamming

Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Vincent de Jong for introducing me to the intricacy of the easyCity action, and for taking the time to answer my questions along my exploration of the case. I also want to thank Robin van t’ Haar for his surprising, and unique, contribution to my investigations of the easyCity action. Rozalinda Borcila, the insights you have shared with me have been a crucial reminder of my own privilieged position – your reflections, I hope, also became a marker in what I have written. Also, I would like to thank others that somehow made my fieldwork possible, and influenced my ‘learning’ of activism and culture jamming. Of these I would especially like to thank Nina Haukeland for introducing me to the politics of activism, Kirsti Hyldmo for reminding me of the realities of exploitation, Åse Brandvold for a skilled introduction to the thoughts and tools of culture jamming, and Maria Astrup for showing me the pleasures and powers of aesthetics. Also, I would like to thank the Norwegian Adbusters Network, and the editorial groups of Vreng. To my main advisor Professor Kristian Stokke, I would like to thank you for the excellent support you have given me throughout my master studies. Your insights have been of grate value, and I cannot thank you enough for continually challenging me. Also, the feedback from Olve Krange, my second advisor, was crucial at the early stage of developing the thesis, to defining its object of inquiry, and finally when writing my conclusion. I would also like to express my appreciation to Professor Oddrun Sæther for an excellent introduction to the field of cultural studies, to Professor Matt Sparke at the University of Washington for demonstrating the intriguing complexities of political geography, and to PhD candidate Stephen Young, for proof reading and fruitful inputs at the final stage of writing. -

Exploring Emotional Intelligence Applications to Challenging Leadership Situations and Reputational Attacks

Exploring Emotional Intelligence Applications to Challenging Leadership Situations and Reputational Attacks Claudia Fernandez, DrPH, MS, RD, LDN Food Systems Leadership Institute February, 2019 Too few people live together in Harmony… It is true…Harmony is quite under-populated. But maybe that’s because we over-rely on the hard skills Hard Skills are the standard skills Budget and finance issues Delivery of clinical treatments or technical services Measurement Accounting Product Design and Development What are the biggest challenges? Budgets Strategic Planning Issues Organizational culture problems Inability to grasp the impacts of one’s actions Inability to communicate and understand one another Leading Managing Change Conflict Building Culture Developing a Team Kouzes & Posner Emotional Intelligence What you use when the hard skills simply can’t get you there And when you’re dealing with complexity, well, that likely to be a lot of the time… Aren’t smart people successful people? Yes, but…not universally People are hired for their technical knowledge, intelligence, and other related factors People derail in their careers over relationship issues—over issues of being unable to understand others, communicate with them, build bridges and alliances So there seems to be something else at play here… EI/EQ is a genuine ability to Build bridges and alliances Mend damaged relationships Empathize Be resilient Manage impulses and stress When do you first know things are off course? Unconsciously competent Consciously competent Consciously incompetent -

Hacking Global Justice Paper Prepared

Hacking Global Justice Paper prepared for: Changing Politics through Digital Networks October 5-6, 2007 Universitá degli Studi di Firenze Florence, Italy Jeffrey S. Juris Assistant Professor of Anthropology Department of Social & Behavioral Sciences New College of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences Arizona State University [email protected] Hacking Global Justice On November 30, 1999, as tens of thousands of protesters blockaded the World Trade Organization (WTO) Summit in Seattle, the electrohippies organized a simultaneous collective action in cyberspace. The U.K.-based collective, composed of environmentalists and computer programmers, developed a special website allowing activists from around the world to take part in a “virtual sit-in.” Using Floodnet software developed by the Electronic Disturbance Theater (EDT) during previous actions supporting the Zapatistas, the electrohippies’ site automatically transferred visitors en masse to the official WTO domain as if thousands of surfers repeatedly clicked their browser reload buttons at the same time. The action was designed to overload the WTO web server by sending multiple requests over a period of several days. The electrohippies claimed more than 450,000 people ultimately swamped the WTO site from November 30 to December 5, while participants sent an additional 900 e-mails to the server per day. The group later explained their action in this way, "In conventional sit-ins people try to occupy gateways or buildings. In a virtual sit-in people from around the globe can occupy the gateway to the WTO’s web servers. In this way we hope to block the flow of information from the conference- which is significant because it will cement proposals to expand globalization in the 21st Century."1 The virtual sit-in against the WTO is an example of what activists call Electronic Civil Disobedience (ECD), an information-age tactic intricately tied to an emerging wave of resistance against corporate globalization (cf. -

Evaluation Report 25 November 2020

Frame, Voice, Report! Final Evaluation Report 25 November 2020 Submitted by: Name: 4G eval s.r.o. Address: Pod Havlínem 217, 156 00 Praha 5, Czech Republic Contact Person: Marie Körner, [email protected] CONTENT Executive summary 1 1. Background 5 1.1. Introduction 5 1.2. Awareness raising of and engagement in SDGs in the EU 5 1.3. Program background 5 1.4. Objectives, use and scope of evaluation 7 1.5. Evaluation criteria and questions 7 1.6. Key evaluation stakeholders 8 2. METHODOLOGY 11 2.1. Approach 11 2.2. Data collection tools and methods 11 2.3. Data analysis and synthesis 13 2.4. Assumptions and limitations 13 3. FINDINGS 14 3.1. FVR! contribution to public awareness of & engagement in SDGs and 3 priorities (EQ1) 14 3.2. Key influencing factors of public awareness and engagement (EQ2) 20 3.3. FVR! contribution to outreach of grantees´ communication (EQ3) 23 3.4. How FVR! toolkit and learning process served grantees and media partners in understanding and using the FVR! principles (EQ4) 25 3.5. How the FVR! toolkit and learning process served grantees and media in working with the 3 thematic priorities (EQ5) 29 3.6. Unintended outcomes of FVR! for third parties (EQ6) 31 3.7. Effectiveness / efficiency of the sub-granting scheme management (EQ7) 33 3.8. Major takeaways for FVR! partners (EQ8+9) 36 3.9. Effectiveness of cooperation among FVR! partners (EQ10) 38 3.10. Unintended outcomes for FVR! partners (EQ11) 38 3.11. Unintended outcomes of in the target countries/regions (EQ12) 39 3.12. -

Contentious Politics, Culture Jamming, and Radical

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2009 Boxing with shadows: contentious politics, culture jamming, and radical creativity in tactical innovation David Matthew Iles, III Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Iles, III, David Matthew, "Boxing with shadows: contentious politics, culture jamming, and radical creativity in tactical innovation" (2009). LSU Master's Theses. 878. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/878 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOXING WITH SHADOWS: CONTENTIOUS POLITICS, CULTURE JAMMING, AND RADICAL CREATIVITY IN TACTICAL INNOVATION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Political Science by David Matthew Iles, III B.A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2006 May, 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis was completed with the approval and encouragement of my committee members: Dr. Xi Chen, Dr. William Clark, and Dr. Cecil Eubanks. Along with Dr. Wonik Kim, they provided me with valuable critical reflection whenever the benign clouds of exhaustion and confidence threatened. I would also like to thank my friends Nathan Price, Caroline Payne, Omar Khalid, Tao Dumas, Jeremiah Russell, Natasha Bingham, Shaun King, and Ellen Burke for both their professional and personal support, criticism, and impatience throughout this process. -

A Virtual World Is Possible. from Tactical Media to Digital Multitudes

A Virtual World is Possible. From Tactical Media to Digital Multitudes http://www.uoc.edu/artnodes/eng/art/lovink_schneider0603/lovink_schneider0603.html A Virtual World is Possible. From Tactical Media to Digital Multitudes Geert Lovink Media Theorist and Activist [email protected] Florian Schneider Writer, Filmmaker and Net Activist [email protected] Abstract: We start with the current strategy debates of the so-called "anti-globalisation movement", the biggest emerging political force for decades. In Part II we will look into strategies of critical new media culture in the post-speculative phase after dotcommania. Four phases of the global movement are becoming visible, all of which have distinct political, artistic and aesthetic qualities. 1. Part I 1.1. The 90s and tactical media activism The term 'tactical media' arose in the aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall as a renaissance of media activism, blending old school political work and artists' engagement with new technologies. The early nineties saw a growing awareness of gender issues, exponential growth of media industries and the increasing availability of cheap do-it-yourself equipment creating a new sense of self-awareness amongst activists, programmers, theorists, curators and artists. Media were no longer seen as merely tools for the Struggle, but experienced as virtual environments whose parameters were permanently 'under construction'. This was the golden age of tactical media, open to issues of aesthetics and experimentation with alternative forms of story telling. However, these liberating techno practices did not immediately translate into visible social movements. Rather, they symbolized the celebration of media freedom, in itself a great political goal. -

The Rebellion of the ACAPD”

Revista Latina de Comunicación Social # 069 – Pages 307 to 329 Funded research | DOI: 10.4185/RLCS-2014-1013en | ISSN 1138-5820 | Year 2014 How to cite this article in bibliograhies / References IA del Amo, A Letamendia, J Diaux (2014): “New communicative resistances: the rebellion of the ACAPD”. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 69, pp. 307 to 329. http://www.revistalatinacs.org/069/paper/1013_UPV/16aen.html DOI: 10.4185/RLCS-2014-1013en New communicative resistances: the rebellion of the ACAPD IA del Amo [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Universidad del País Vasco / Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, UPV/EHU / University of the Basque Country – [email protected] A Letamendia [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Universidad del País Vasco / Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, UPV/EHU / University of the Basque Country – [email protected] J Diaux [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Universidad del País Vasco / Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, UPV/EHU / University of the Basque Country – [email protected] Abstract Introduction. This article aims to make a contribution to the debate on the role of the media in the cultivation of assumptions about reality, especially after the emergence of the new Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs). Objectives. The study focuses on the analysis of two specific new forms of communicative conflict that have been used in social movements: the protest lip dubs and videos of police misconduct filmed by civilians. Both of these communicative forms are types of what we have termed Audiovisual Cultural Artefacts of Protest and Demand (ACAPD). Method. The study is based on a theoretical analysis of the relationship between power, communication and resistance, and offers an interpretation of the different dimensions in which resistance and conflict are articulated. -

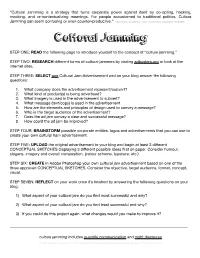

Cultural Jamming Is a Strategy That Turns Corporate Power Against Itself by Co-Opting, Hacking, Mocking, and Re-Contextualizing Meanings

“Cultural Jamming is a strategy that turns corporate power against itself by co-opting, hacking, mocking, and re-contextualizing meanings. For people accustomed to traditional politics, Culture Jamming can seem confusing or even counter-productive.” http://depts.washington.edu/ccce/polcommcampaigns/peretti.html ! Cultural Jamming ! !STEP ONE: READ the following page to introduce yourself to the concept of “culture jamming.” STEP TWO: RESEARCH different forms of cultural jammers by visiting adbusters.org or look at the !internet sites. STEP THREE: SELECT one Cultural Jam Advertisement and on your blog answer the following !questions: 1. What company does the advertisement represent/subvert? 2. What kind of product(s) is being advertised? 3. What imagery is used in the advertisement to subvert? 4. What message (text/copy) is used in the advertisement 5. How are the elements and principles of design used to convey a message? 6. Who is the target audience of the advertisement? 7. Does the ad jam convey a clear and successful message? ! 8. How could the ad jam be improved? STEP FOUR: BRAINSTORM possible corporate entities, logos and advertisements that you can use to !create your own cultural ham advertisement. STEP FIVE: UPLOAD the original advertisement to your blog and begin at least 3 different CONCEPTUAL SKETCHES displaying 3 different possible ideas first on paper. Consider humour, !slogans, imagery and overall composition. (colour scheme, typeface, etc.) STEP SIX: CREATE in Adobe Photoshop your own cultural jam advertisement based on one of the three approved CONCEPTUAL SKETCHES. Consider the objective, target audience, format, concept, !visual. STEP SEVEN: REFLECT on your work once it’s finished by answering the following questions on your !blog. -

Modern Guerrilla Tactics

Guerrilla Tactics Guerrilla Tactics The Use of Decoy Rockets and Missiles Fire decoy missiles and rockets at the enemy in order to overwhelm their anti-missile systems (Patriot, Iron Dome, etc.). Decoy missiles and rockets can be fired first, then followed up by the real missiles and rockets or the decoys can be mixed in with the real. The objective is to get the enemy to shoot down the decoys and possibly run out of missiles. The decoys are, on the other hand, cheap and inexpensive rockets or perhaps some could be specialized missiles that disrupt enemy radar, etc. Perhaps hundreds of balloons with thin strips of aluminum attached to them are sent up to confuse enemy radar or balloons made of thin foil like material. Done to confuse enemy radar during a missile or rocket barrage. Decoy rockets positioned on the ground. Perhaps fake ground crews "hiding" nearby. Not too well hidden. Used to draw enemy fire away from real rockets and soldiers. Used to waste enemy munitions on false targets. Common Guerrilla Tactics The guerrillas can draw enemy forces out of major population areas and into remote border sanctuaries where supply and escape can be facilitated. This helps undermine enemy pacification efforts on the civilian population and disperses his forces. The enemy cannot send large amounts of soldiers to occupy every city, town, village, block, building, etc. The enemy cannot be strong everywhere. If the enemy is strong in one area, he will be weak in another. Attack the enemy where he is weak, not where he is strong. -

Framing Comedies of Recognition and Repertoires of Tactical Frivolity Within Social Movements A.T

Interface: a journal for and about social movements Article Volume 8 (2): pp. 286 - 310 (November 2016) Kingsmith, Why so serious? Why so serious? Framing comedies of recognition and repertoires of tactical frivolity within social movements A.T. Kingsmith Abstract What makes something funny? That depends. When it comes to humour, we are all experts. We know what we find funny. Such ambiguity is one of the central reasons a phenomenological analysis of humour as a means for radical political subject formations has been neglected within the study of social movements. Yet in many contexts a joke can represent liberation from pressure, rebellion against authority, a subversive political performance. We might even say that given common social norms and linguistic signifiers, joke telling can tear holes in our usual predictions about the empirical world by creating disjunctions between actuality and representation. After all, those in power have little recourse against mockery. Responding harshly to silence humorous actions tends to in fact increase the laughter. As such, humour must be appreciated not just as comic relief, but as a form of ideological emancipation, a means of deconstructing our social realities, and at the same time, imagining and proposing alternative ones. By informing this notion of humour as subversive political performance with one of the most instrumental approaches to social movement studies, Charles Tilly’s repertoires of contention, this paper begins by framing the dangers of comedic containment, before theorising the creative and electronic turns in social movement studies through a lens of rebellious humour as a post-political act. The paper emphasises these contributions with two unique explorations of political humour: 1970s’ radio frivolity by the post-Marxist Italian Autonomous movement, and present day Internet frivolousness by the hacktivist collective Anonymous. -

Media Art [email protected]

Paolo Cirio – Media Art [email protected] - www.paolocirio.net A workshop on tactical Guerrilla Communication More material and information about the workshop: http://www.paolocirio.net/press/workshop/workshop_guerrilla-communication.php by Paolo Cirio. Information about the artist Paolo Cirio: http://www.paolocirio.net Terms such as Semiotization, Virality, Participation, Contagion, Buzz, etc. are familiar in politics and marketing. They arose out of pioneering experiences and analyses of a networked and mediatized society. Finally, they are now our reality. The workshop will analyze some of the most recent and radical theories of media communication. A final practical section will allow students to realize enhanced unconventional communication and explore innovative techniques. Knowledge of the history of attempts to control perceptions of social reality, and a well-developed interest in manipulating information are both relevant skills for developing communication using appropriate tools and methodologies. The aim of the workshop is to forge warriors and devices of media-seduction, experts of effective campaigns and alternative realities makers. They will become familiar with the weapons of radical biz; shock marketing, agit-prop tactics, pandemic viral campaigns, psychological torture, obsessive desire and fabricated hate. The course would be useful for anyone who wants to improve their ability to influence and educate society for specific purposes, through developing smart, strategic languages designed for particular media tools. The below list of theories is indicative for the content of the workshop, and each one will be combined with successful practical examples of political, commercial and artistic guerrilla communication solutions. The Power of Desire Convergence Culture The Language of Change. -

Italian Media Activism and the Repurposing of the Social

From Collectives to Connectives: Italian Media Activism and the Repurposing of the Social by Alessandra Renzi A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology and Equity Studies Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Alessandra Renzi 2011 From Collectives to Connectives: Italian Media Activism and the Repurposing of the Social Alessandra Renzi Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology and Equity Studies Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto 2011 Abstract The dissertation develops the concept of repurposing as a means for thinking with activists and the issues they confront. It moves alongside pirate television collective insu^tv as they draw on a variety of histories, traditions and technological resources for their practices. Repurposing functions on multiple levels and at multiple scales, from the recycling of materials and spaces to the harnessing and relaying of encounters and events within an ever-expanding field of social relations. When seen as a way of connecting activist groups and communities, the repurposing of media contributes to strengthening an often fragmented and conflicted activist field. Indeed, insu^tv’s use of information and technology brings to the fore the value of media activism for the creation of social assemblages in which the “media” literally mediates between individuals and among individuals and their environment, instituting and developing an ontogenetic relation (Simondon, 1989). Yet, rather than simply making sense of insu^tv’s practices, the concept of repurposing also provokes a discussion regarding the ethics of connection. For insu^tv, this connective ethics can be understood as a set of rules and principles that facilitate the ii evaluation of actions, communication, and thought according to an immanent mode of collective existence (Deleuze, 1988; Simondon, 1989).