Arxiv:1606.03013V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 9 Jun 2016 N-Rie Iiae Eeye L 06.Seta Mod- Spectral of 2006)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solar System Tests of the Equivalence Principle and Constraints on Higher-Dimensional Gravity

Solar system tests of the equivalence principle and constraints on higher-dimensional gravity J. M. Overduin Department of Physics, University of Waterloo, ON, Canada N2L 3G1 and Gravity Probe B, Hansen Experimental Physics Laboratory, Stanford University, California (July 21, 2000) the theory, ξ and αk refer to possible preferred-location In most studies of equivalence principle violation by solar and preferred-frame effects, and the ζk allow for possible system bodies, it is assumed that the ratio of gravitational to violations of momentum conservation (see [1] for discus- inertial mass for a given body deviates from unity by a param- sion). One has η = 0 in standard general relativity, where eter ∆ which is proportional to its gravitational self-energy. γ = β = 1. In 4D scalar-tensor theories, by contrast, Here we inquire what experimental constraints can be set on γ =(1+ω)/(2 + ω)andβ =1+ω /[2(2 + ω)(3 + 2ω)2], ∆ for various solar system objects when this assumption is re- 0 laxed. Extending an analysis originally due to Nordtvedt, we where ω = ω(φ) is the generalized Brans-Dicke parame- obtain upper limits on linearly independent combinations of ter and ω0 = dω/dφ. ∆ for two or more bodies from Kepler’s third law, the position The relative gravitational self-energy U can be cal- of Lagrange libration points, and the phenomenon of orbital culated for most objects in the solar system, subject polarization. Combining our results, we extract numerical to uncertainties in their mass density profiles. Thus, 5 upper bounds on ∆ for the Sun, Moon, Earth and Jupiter, for example, US 10− for the Sun, while Jupiter 8 ∼− using observational data on their orbits as well as those of the has UJ 10− [3]. -

Occultation Newsletter Volume 8, Number 4

Volume 12, Number 1 January 2005 $5.00 North Am./$6.25 Other International Occultation Timing Association, Inc. (IOTA) In this Issue Article Page The Largest Members Of Our Solar System – 2005 . 4 Resources Page What to Send to Whom . 3 Membership and Subscription Information . 3 IOTA Publications. 3 The Offices and Officers of IOTA . .11 IOTA European Section (IOTA/ES) . .11 IOTA on the World Wide Web. Back Cover ON THE COVER: Steve Preston posted a prediction for the occultation of a 10.8-magnitude star in Orion, about 3° from Betelgeuse, by the asteroid (238) Hypatia, which had an expected diameter of 148 km. The predicted path passed over the San Francisco Bay area, and that turned out to be quite accurate, with only a small shift towards the north, enough to leave Richard Nolthenius, observing visually from the coast northwest of Santa Cruz, to have a miss. But farther north, three other observers video recorded the occultation from their homes, and they were fortuitously located to define three well- spaced chords across the asteroid to accurately measure its shape and location relative to the star, as shown in the figure. The dashed lines show the axes of the fitted ellipse, produced by Dave Herald’s WinOccult program. This demonstrates the good results that can be obtained by a few dedicated observers with a relatively faint star; a bright star and/or many observers are not always necessary to obtain solid useful observations. – David Dunham Publication Date for this issue: July 2005 Please note: The date shown on the cover is for subscription purposes only and does not reflect the actual publication date. -

Ty996i the Astronomical Journal Volume 71, Number

coPC THE ASTRONOMICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 71, NUMBER 6 AUGUST 1966 TY996I Observations of Comets, Minor Planets, and Satellites Elizabeth Roemer* and Richard E. Lloyd U. S. Naval Observatory, Flagstaff Station, Arizona (Received 10 May 1966) Accurate positions and descriptive notes are presented for 38 comets, 33 minor planets, 5 faint natural satellites, and Pluto, for which astrometric reduction of the series of Flagstaff observations has been completed. THE 1022 positions and descriptive notes presented reference star positions; therefore, she bears responsi- here supplement those given by Roemer (1965), bility for the accuracy of the results given here. who also described the program, the equipment used, Coma diameters and tail dimensions given in the and the procedures of observation and of reduction. Notes to Table I refer to the exposures taken for In this paper as in the earlier one, the participation astrometric purposes unless otherwise stated. In of those who shared in critical phases of the work is general, longer exposures show more extensive head and indicated in the Obs/Meas column of Table I according tail structure. to the following letters: For brighter comets the minimum exposure is determined by the necessity of recording measurable R=Elizabeth Roemer. images of 12th-13th magnitude reference stars. On Part-time assistants under contract Nonr-3342(00) such exposures the position of the nuclear condensation with Lowell Observatory: may be more or less obscured by the overexposed coma and be correspondingly difficult and uncertain to L = Richard E. Lloyd, measure. T = Maryanna Thomas, A colon has been used to indicate greater than normal S = Marjorie K. -

On the Accuracy of Restricted Three-Body Models for the Trojan Motion

DISCRETE AND CONTINUOUS Website: http://AIMsciences.org DYNAMICAL SYSTEMS Volume 11, Number 4, December 2004 pp. 843{854 ON THE ACCURACY OF RESTRICTED THREE-BODY MODELS FOR THE TROJAN MOTION Frederic Gabern1, Angel` Jorba1 and Philippe Robutel2 Departament de Matem`aticaAplicada i An`alisi Universitat de Barcelona Gran Via 585, 08007 Barcelona, Spain1 Astronomie et Syst`emesDynamiques IMCCE-Observatoire de Paris 77 Av. Denfert-Rochereau, 75014 Paris, France2 Abstract. In this note we compare the frequencies of the motion of the Trojan asteroids in the Restricted Three-Body Problem (RTBP), the Elliptic Restricted Three-Body Problem (ERTBP) and the Outer Solar System (OSS) model. The RTBP and ERTBP are well-known academic models for the motion of these asteroids, and the OSS is the standard model used for realistic simulations. Our results are based on a systematic frequency analysis of the motion of these asteroids. The main conclusion is that both the RTBP and ERTBP are not very accurate models for the long-term dynamics, although the level of accuracy strongly depends on the selected asteroid. 1. Introduction. The Restricted Three-Body Problem models the motion of a particle under the gravitational attraction of two point masses following a (Keple- rian) solution of the two-body problem (a general reference is [17]). The goal of this note is to discuss the degree of accuracy of such a model to study the real motion of an asteroid moving near the Lagrangian points of the Sun-Jupiter system. To this end, we have considered two restricted three-body problems, namely: i) the Circular RTBP, in which Sun and Jupiter describe a circular orbit around their centre of mass, and ii) the Elliptic RTBP, in which Sun and Jupiter move on an elliptic orbit. -

HUBBLE ULTRAVIOLET SPECTROSCOPY of JUPITER TROJANS Ian Wong1†, Michael E

Draft version March 11, 2019 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 12/16/11 HUBBLE ULTRAVIOLET SPECTROSCOPY OF JUPITER TROJANS Ian Wong1y, Michael E. Brown2, Jordana Blacksberg3, Bethany L. Ehlmann2,3, and Ahmed Mahjoub3 1Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA; [email protected] 2Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 3Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA y51 Pegasi b Postdoctoral Fellow Draft version March 11, 2019 ABSTRACT We present the first ultraviolet spectra of Jupiter Trojans. These observations were carried out using the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph on the Hubble Space Telescope and cover the wavelength range 200{550 nm at low resolution. The targets include objects from both of the Trojan color sub- populations (less-red and red). We do not observe any discernible absorption features in these spectra. Comparisons of the averaged UV spectra of less-red and red targets show that the subpopulations are spectrally distinct in the UV. Less-red objects display a steep UV slope and a rollover at around 450 nm to a shallower visible slope, whereas red objects show the opposite trend. Laboratory spectra of irradiated ices with and without H2S exhibit distinct UV absorption features; consequently, the featureless spectra observed here suggest H2S alone is not responsible for the observed color bimodal- ity of Trojans, as has been previously hypothesized. We propose some possible explanations for the observed UV-visible spectra, including complex organics, space weathering of iron-bearing silicates, and masked features due to previous cometary activity. -

Astrocladistics of the Jovian Trojan Swarms

MNRAS 000,1–26 (2020) Preprint 23 March 2021 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 Astrocladistics of the Jovian Trojan Swarms Timothy R. Holt,1,2¢ Jonathan Horner,1 David Nesvorný,2 Rachel King,1 Marcel Popescu,3 Brad D. Carter,1 and Christopher C. E. Tylor,1 1Centre for Astrophysics, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, QLD, Australia 2Department of Space Studies, Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, CO. USA. 3Astronomical Institute of the Romanian Academy, Bucharest, Romania. Accepted XXX. Received YYY; in original form ZZZ ABSTRACT The Jovian Trojans are two swarms of small objects that share Jupiter’s orbit, clustered around the leading and trailing Lagrange points, L4 and L5. In this work, we investigate the Jovian Trojan population using the technique of astrocladistics, an adaptation of the ‘tree of life’ approach used in biology. We combine colour data from WISE, SDSS, Gaia DR2 and MOVIS surveys with knowledge of the physical and orbital characteristics of the Trojans, to generate a classification tree composed of clans with distinctive characteristics. We identify 48 clans, indicating groups of objects that possibly share a common origin. Amongst these are several that contain members of the known collisional families, though our work identifies subtleties in that classification that bear future investigation. Our clans are often broken into subclans, and most can be grouped into 10 superclans, reflecting the hierarchical nature of the population. Outcomes from this project include the identification of several high priority objects for additional observations and as well as providing context for the objects to be visited by the forthcoming Lucy mission. -

Colours of Minor Bodies in the Outer Solar System II - a Statistical Analysis, Revisited

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. MBOSS2 c ESO 2012 April 26, 2012 Colours of Minor Bodies in the Outer Solar System II - A Statistical Analysis, Revisited O. R. Hainaut1, H. Boehnhardt2, and S. Protopapa3 1 European Southern Observatory (ESO), Karl Schwarzschild Straße, 85 748 Garching bei M¨unchen, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 2 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Sonnensystemforschung, Max-Planck Straße 2, 37 191 Katlenburg- Lindau, Germany 3 Department of Astronomy, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20 742-2421, USA Received —; accepted — ABSTRACT We present an update of the visible and near-infrared colour database of Minor Bodies in the outer Solar System (MBOSSes), now including over 2000 measurement epochs of 555 objects, extracted from 100 articles. The list is fairly complete as of December 2011. The database is now large enough that dataset with a high dispersion can be safely identified and rejected from the analysis. The method used is safe for individual outliers. Most of the rejected papers were from the early days of MBOSS photometry. The individual measurements were combined so not to include possible rotational artefacts. The spectral gradient over the visible range is derived from the colours, as well as the R absolute magnitude M(1, 1). The average colours, absolute magnitude, spectral gradient are listed for each object, as well as their physico-dynamical classes using a classification adapted from Gladman et al., 2008. Colour-colour diagrams, histograms and various other plots are presented to illustrate and in- vestigate class characteristics and trends with other parameters, whose significance are evaluated using standard statistical tests. -

The Minor Planet Bulletin

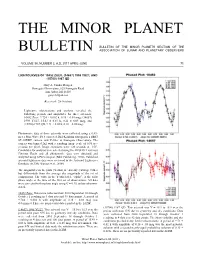

THE MINOR PLANET BULLETIN OF THE MINOR PLANETS SECTION OF THE BULLETIN ASSOCIATION OF LUNAR AND PLANETARY OBSERVERS VOLUME 38, NUMBER 2, A.D. 2011 APRIL-JUNE 71. LIGHTCURVES OF 10452 ZUEV, (14657) 1998 YU27, AND (15700) 1987 QD Gary A. Vander Haagen Stonegate Observatory, 825 Stonegate Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 [email protected] (Received: 28 October) Lightcurve observations and analysis revealed the following periods and amplitudes for three asteroids: 10452 Zuev, 9.724 ± 0.002 h, 0.38 ± 0.03 mag; (14657) 1998 YU27, 15.43 ± 0.03 h, 0.21 ± 0.05 mag; and (15700) 1987 QD, 9.71 ± 0.02 h, 0.16 ± 0.05 mag. Photometric data of three asteroids were collected using a 0.43- meter PlaneWave f/6.8 corrected Dall-Kirkham astrograph, a SBIG ST-10XME camera, and V-filter at Stonegate Observatory. The camera was binned 2x2 with a resulting image scale of 0.95 arc- seconds per pixel. Image exposures were 120 seconds at –15C. Candidates for analysis were selected using the MPO2011 Asteroid Viewing Guide and all photometric data were obtained and analyzed using MPO Canopus (Bdw Publishing, 2010). Published asteroid lightcurve data were reviewed in the Asteroid Lightcurve Database (LCDB; Warner et al., 2009). The magnitudes in the plots (Y-axis) are not sky (catalog) values but differentials from the average sky magnitude of the set of comparisons. The value in the Y-axis label, “alpha”, is the solar phase angle at the time of the first set of observations. All data were corrected to this phase angle using G = 0.15, unless otherwise stated. -

Appendix 1 1311 Discoverers in Alphabetical Order

Appendix 1 1311 Discoverers in Alphabetical Order Abe, H. 28 (8) 1993-1999 Bernstein, G. 1 1998 Abe, M. 1 (1) 1994 Bettelheim, E. 1 (1) 2000 Abraham, M. 3 (3) 1999 Bickel, W. 443 1995-2010 Aikman, G. C. L. 4 1994-1998 Biggs, J. 1 2001 Akiyama, M. 16 (10) 1989-1999 Bigourdan, G. 1 1894 Albitskij, V. A. 10 1923-1925 Billings, G. W. 6 1999 Aldering, G. 4 1982 Binzel, R. P. 3 1987-1990 Alikoski, H. 13 1938-1953 Birkle, K. 8 (8) 1989-1993 Allen, E. J. 1 2004 Birtwhistle, P. 56 2003-2009 Allen, L. 2 2004 Blasco, M. 5 (1) 1996-2000 Alu, J. 24 (13) 1987-1993 Block, A. 1 2000 Amburgey, L. L. 2 1997-2000 Boattini, A. 237 (224) 1977-2006 Andrews, A. D. 1 1965 Boehnhardt, H. 1 (1) 1993 Antal, M. 17 1971-1988 Boeker, A. 1 (1) 2002 Antolini, P. 4 (3) 1994-1996 Boeuf, M. 12 1998-2000 Antonini, P. 35 1997-1999 Boffin, H. M. J. 10 (2) 1999-2001 Aoki, M. 2 1996-1997 Bohrmann, A. 9 1936-1938 Apitzsch, R. 43 2004-2009 Boles, T. 1 2002 Arai, M. 45 (45) 1988-1991 Bonomi, R. 1 (1) 1995 Araki, H. 2 (2) 1994 Borgman, D. 1 (1) 2004 Arend, S. 51 1929-1961 B¨orngen, F. 535 (231) 1961-1995 Armstrong, C. 1 (1) 1997 Borrelly, A. 19 1866-1894 Armstrong, M. 2 (1) 1997-1998 Bourban, G. 1 (1) 2005 Asami, A. 7 1997-1999 Bourgeois, P. 1 1929 Asher, D. -

The Origin and Evolution of Celestial Bodies Gravitating in the Vicinity of Earth’S Orbit

“BABES¸-BOLYAI” UNIVERSITY, CLUJ-NAPOCA FACULTY OF MATHEMATICS AND COMPUTER SCIENCE THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF CELESTIAL BODIES GRAVITATING IN THE VICINITY OF EARTH’S ORBIT -doctoral thesis- EXTENDED ABSTRACT S¸tefan Gh. Berinde Research supervisor: Prof. Dr. Vasile Ureche June 2002 Additional information about this work can be found at the following internet address: http://math.ubbcluj.ro/»sberinde/thesis Thesis content Introduction Abbreviations Chapter 1. Population description 1.1 Observational evidences 1.2 Observational biases Chapter 2. Dynamics of close encounters 2.1 The restricted three-body problem 2.1.1 Equations of motion 2.1.2 Jacobi integral 2.1.3 Tisserand criterion 2.1.4 Lagrange equilibrium points 2.1.5 Hill’s equations 2.2 Opik’s¨ geometric formalism 2.2.1 Motion characteristics 2.2.2 Motion outside the planetary sphere of action 2.2.3 Motion inside the planetary sphere of action 2.2.4 A complete map of orbital changes Chapter 3. Characteristics of long-term dynamical evolution 3.1 Chaotic behaviour 3.1.1 Chaos in the planar, circular, restricted three-body problem 3.1.2 Lyapounov exponents 3.1.3 Effects of chaos on long-term numerical integrations 3.2 Resonant motions 3.2.1 Mean motion resonances 3.2.2 Secular resonances 3.2.3 Protection mechanisms 3.3 Dynamical classifications 3.3.1 Classification against minimal orbital intersection distance 3.3.2 SPACEGUARD classification Chapter 4. Source regions and dynamical transport mechanisms 4.1 The main belt of asteroids as NEA source 4.1.1 Dynamical structure of the asteroid belt 4.1.2 Transport mechanisms to the inner solar system 4.1.3 The role of inter-asteroidal collisions 4.1.4 Estimating the mass of asteroids 4.2 NEA asteroids of cometary origin 4.2.1 Populations of bodies in the outer solar system 4.2.2 Chaotic diffusion of bodies from the Kuiper belt to the inner solar system Chapter 5. -

2004 KV18: a Visitor from the Scattered Disc to the Neptune Trojan Population � J

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 426, 159–166 (2012) doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21717.x 2004 KV18: a visitor from the scattered disc to the Neptune Trojan population J. Horner1 and P. S. Lykawka2 1Department of Astrophysics, School of Physics, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia 2Astronomy Group, Faculty of Social and Natural Sciences, Kinki University, Shinkamikosaka 228-3, Higashiosaka-shi, Osaka 577-0813, Japan Accepted 2012 July 12. Received 2012 July 12; in original form 2012 June 14 ABSTRACT Downloaded from We have performed a detailed dynamical study of the recently identified Neptunian Trojan 2004 KV18, only the second object to be discovered librating around Neptune’s trailing Lagrange point, L5. We find that 2004 KV18 is moving on a highly unstable orbit, and was most likely captured from the Centaur population at some point in the last ∼1 Myr, having originated in http://mnras.oxfordjournals.org/ the scattered disc, beyond the orbit of Neptune. The instability of 2004 KV18 is so great that many of the test particles studied leave the Neptunian Trojan cloud within just ∼0.1–0.3 Myr, and it takes just 37 Myr for half of the 91 125 test particles created to study its dynamical behaviour to be removed from the Solar system entirely. Unlike the other Neptunian Trojans previously found to display dynamical instability on 100-Myr time-scales (2001 QR322 and 2008 LC18), 2004 KV18 displays such extreme instability that it must be a temporarily captured Trojan, rather than a primordial member of the Neptunian Trojan population. -

Updated on 1 September 2018

20813 Aakashshah 12608 Aesop 17225 Alanschorn 266 Aline 31901 Amitscheer 30788 Angekauffmann 2341 Aoluta 23325 Arroyo 15838 Auclair 24649 Balaklava 26557 Aakritijain 446 Aeternitas 20341 Alanstack 8651 Alineraynal 39678 Ammannito 11911 Angel 19701 Aomori 33179 Arsenewenger 9117 Aude 16116 Balakrishnan 28698 Aakshi 132 Aethra 21330 Alanwhitman 214136 Alinghi 871 Amneris 28822 Angelabarker 3810 Aoraki 29995 Arshavsky 184535 Audouze 3749 Balam 28828 Aalamiharandi 1064 Aethusa 2500 Alascattalo 108140 Alir 2437 Amnestia 129151 Angelaboggs 4094 Aoshima 404 Arsinoe 4238 Audrey 27381 Balasingam 33181 Aalokpatwa 1142 Aetolia 19148 Alaska 14225 Alisahamilton 32062 Amolpunjabi 274137 Angelaglinos 3400 Aotearoa 7212 Artaxerxes 31677 Audreyglende 20821 Balasridhar 677 Aaltje 22993 Aferrari 200069 Alastor 2526 Alisary 1221 Amor 16132 Angelakim 9886 Aoyagi 113951 Artdavidsen 20004 Audrey-Lucienne 26634 Balasubramanian 2676 Aarhus 15467 Aflorsch 702 Alauda 27091 Alisonbick 58214 Amorim 30031 Angelakong 11258 Aoyama 44455 Artdula 14252 Audreymeyer 2242 Balaton 129100 Aaronammons 1187 Afra 5576 Albanese 7517 Alisondoane 8721 AMOS 22064 Angelalewis 18639 Aoyunzhiyuanzhe 1956 Artek 133007 Audreysimmons 9289 Balau 22656 Aaronburrows 1193 Africa 111468 Alba Regia 21558 Alisonliu 2948 Amosov 9428 Angelalouise 90022 Apache Point 11010 Artemieva 75564 Audubon 214081 Balavoine 25677 Aaronenten 6391 Africano 31468 Albastaki 16023 Alisonyee 198 Ampella 25402 Angelanorse 134130 Apaczai 105 Artemis 9908 Aue 114991 Balazs 11451 Aarongolden 3326 Agafonikov 10051 Albee