What About Drug Checking? Systematic Review and Netnographic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bridging the Gap: a Practitioner's Guide to Harm Reduction in Drug

Bridging the Gap A Practitioner’s Guide to Harm Reduction in Drug Courts by Alejandra Garcia and Dave Lucas a Author Alejandra Garcia, MSW Center for Court Innovation Dave Lucas, MSW Center for Court Innovation Acknowledgements Bridging the Gap: A Practitioners Guide to Harm Reduction in Drug Courts represents an ambitious reimagining of drug court practices through a harm reduction lens. It was born of two intersecting health emergencies—COVID-19 and the overdose crisis—and a belief that this moment calls for challenging conversations and bold change. Against this backdrop, Bridging the Gap’s first aim is plain: to elevate the safety, dignity, and autonomy of current and future drug court participants. It is also an invitation to practitioners to revisit and reflect upon drug court principles from a new vantage point. There are some who see the core tenets of drug courts and harm reduction as antithetical. As such, disagreement is to be expected. Bridging the Gap aspires to be the beginning of an evolving discussion, not the final word. This publication would not have been possible without the support of Aaron Arnold, Annie Schachar, Karen Otis, Najah Magloire, Matt Watkins, and Julian Adler. We are deeply grateful for your thoughtful advice, careful edits, and encouraging words. A special thanks also to our designers, Samiha Amin Meah and Isaac Gertman. Bridging the Gap is dedicated to anyone working to make the world a safer place for people who use drugs. Thanks to all who approach this document with an open mind. For more information, email [email protected]. -

2017 Global Drug Survey

Prepared by the GDS Core Research Team Dr Adam Winstock, Dr Monica Barratt, Dr Jason Ferris & Dr Larissa Maier Global overview and highlights N > 115,000 Global Drug Survey GDS2017 © Not to be reproduced without authors permission Hi everyone On behalf of the GDS Core Research Team and everyone of our amazing international network partners and supportive media organisations we’d like to share our headline report deck. I know it won’t have everything that everyone wants but we are hopeful it will give people an idea of how the world of drugs is changing and highlight some of the key things that we think people can better engage with to keep themselves and those they care for safe. Once we cleaned the data from 150,000 people we chose to use data from just under 120,000 people this year for these reports. We have data reports addressing 18 different areas for over 25 countries. We can only share a fraction of what we have here on the site. However, we are very open to sharing the other findings we have and would ask researchers and public health groups to contact us so we can discuss funding and collaboration. We have almost completed designing GDS2018 so that we can start piloting early and give countries where we have not yet found friends to reach out to us. We particularly want to hear from people in Japan, Eastern Europe, Africa and the Middle East. Dr Adam R Winstock Founder and CEO Global Drug Survey Consultant Psychiatrist and Addiction Medicine Specialist Global Drug Survey GDS2017 © Not to be reproduced without authors permission We think this will be interesting. -

Evaluation of a Drug Checking Service at a Large Scale Electronic Music Festival in Portugal

International Journal of Drug Policy 73 (2019) 88–95 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Drug Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/drugpo Research Paper Evaluation of a drug checking service at a large scale electronic music festival in Portugal T ⁎ Helena Valentea,b,c, , Daniel Martinsb,d, Helena Carvalhoe,f, Cristiana Vale Piresb,g,h, Maria Carmo Carvalhob,h, Marta Pintoa,c,i, Monica J. Barrattj,k a Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the Porto University, Portugal b Kosmicare Association, Portugal c CINTESIS. Centre for Health Technology and Services Research, Portugal d CIQUP. Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Faculty of Sciences of the Porto Univsersity of Porto, Portugal e CPUP. Centre for Psychology of the University of Porto, Portugal f inED. Centre for Research and Innovation in Education, Portugal g Faculty of Education and Psychology of the Portuguese Catholic University, Portugal h CRIA. Centre for Research in Anthropology, Portugal i Faculty of Medicine of the Porto University, Portugal j Social and Global Studies Centre, RMIT University, Australia k National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, Australia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Background: Drug checking services are being implemented in recreational settings across the world, however Harm reduction these projects are frequently accused of a lack of evidence concerning their impact on people who use drugs. This Program evaluation paper describes the implementation of a drug checking service at the Boom Festival 2016 and explores the Drug checking impact of this service on its users’ behavioural intentions. Boom festival Methods: 753 drug samples were submitted to the drug checking service for chemical analysis. -

Year End Report 2019 Year End Report 2019

Vancouver Island Drug Checking Project Year End Report 2019 Year End Report 2019 The Vancouver Island Drug Checking Project delivers drug checking services in Victoria, BC. We currently operate at SOLID Outreach, AVI Health and Community Services, and Lantern Services as well as festivals and community events. This free and confidential service provides information on composition of substances and harm reduction infor- mation. We employ five instruments as follows: Fentanyl Strip Tests Fourier Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Raman Spectroscopy 935 Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) Samples Tested Gas Chromatography – Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) in 2019 What were people bringing to be tested? We asked people what drug they were bringing to be tested. The majority of substances were expected to be heroin or fentanyl (362), a stimulant (234), or a psychedelic (139). Further, many brought unknown samples for testing (73) or did not provide information (56). This may be due in part to people testing for others and bringing multiple samples or hav- ing found substances. The remaining substances were expected to be dissociatives (31), benzodiazepines (16) or other depressants (5), other opioids (5), polysubstance (3) or other (11). Opioid-Down: heroin and/or Stimulant: methampheta- Psychedelic: LSD, MDMA, 362362 fentanyl 234234 mine, cocaine HCl, cocaine base 139139 MDA, 2CB, DMT Unknown Missing Dissociative: ketamine, DXM, 7373 5656 3131 methoxetamine, PCP Depressant- Other Depressant-Other: GHB, 1616 Benzodiazepines 1111 5 GBL, barbiturates, methaqualone, phenibut Opioid-Other: morphine, phar- Polysubstance 55 maceutical opioids 33 Data are not finalized and subject to change. There were missing data for some samples. Vancouver Island Drug Checking Project Year End Report 2019 How many samples tested positive for fentanyl? We tested all samples using Fentanyl Test Strips to determine whether they contained fentanyl. -

Regulation of Drug Checking Services

IN CONFIDENCE In Confidence Office of the Minister of Health Cabinet Social Wellbeing Committee Regulation of drug checking services Proposal 1 This paper seeks agreement to amend the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 and the Psychoactive Substances Act 2013 to enable a permanent system of regulation for drug checking service providers. Relation to government priorities 2 This proposal does not relate to a Government priority. Executive Summary 3 Drug checking services check the composition of illicit drugs and provide harm reduction advice to help individuals make informed decisions about drug use. Where a drug is not as presumed, the individual can make the potentially life-saving decision not to consume it. 4 Drug checking is currently regulated under amendmentsreleased made by the Drug and Substance Checking Legislation Act 2020 (the Drug Checking Act) to the Misuse of Drugs Act and the Psychoactive Substances Act. These amendments allow appointed drug checking service providers to operate with legal certainty. 5 The Drug Checking Act was always intended to be temporary legislation to allow time for a permanent licensing system to be developed. The Drug Checking Act includes mechanisms which will repeal the amendments to the Misuse of Drugs Act and the Psychoactive Substances Act in December 2021. 6 If a permanent system is not in place when the Drug Checking Act repeal provisions take effect, drug checking will revert to a legal grey area. This would impede service provision and make it more difficult to prevent harm from dangerous substances such as synthetic cathinones (sometimes known as “bath salts”). Regulation is required to enable good quality services and to prevent low-quality service providers from operating. -

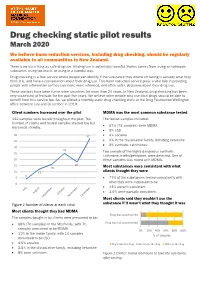

Drug Checking Static Pilot Results

Drug checking static pilot results March 2020 We believe harm reduction services, including drug checking, should be regularly available to all communities in New Zealand. There is no such thing as safe drug use. All drug use is potentially harmful. Harms comes from using an unknown substance, using too much, or using in a harmful way. Drug checking is a free service where people can identify if the substance they intend on taking is actually what they think it is, and have a conversation about their drug use. This harm reduction service plays a vital role in providing people with information so they can make more informed, and often safer, decisions about their drug use. These services have been run in other countries for more than 20 years. In New Zealand, drug checking has been very successful at festivals for the past five years. We believe other people who use illicit drugs should be able to benefit from this service too. So, we piloted a monthly static drug checking clinic at the Drug Foundation Wellington office between July and December in 2019. Client numbers increased over the pilot MDMA was the most common substance tested 112 samples were tested throughout the pilot. The The tested samples included: number of clients and tested samples started low but 67% (75 samples) were MDMA increased steadily. • • 9% LSD 40 37 • 4% cocaine 35 • 4% in the dissociative family, including ketamine • 3% synthetic cathinones. 30 25 Two sample of the highly dangerous synthetic 25 cathinone, n-ethylpentylone, were detected. One of 20 these samples was mixed with MDMA. -

Is Expected Substance Type Associated with Timing of Drug Checking

Beaulieu et al. Harm Reduct J (2021) 18:66 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00514-3 BRIEF REPORT Open Access Is expected substance type associated with timing of drug checking service utilization?: A cross-sectional study Tara Beaulieu1,2, Evan Wood1,3, Samuel Tobias1, Mark Lysyshyn4,5, Priya Patel1, Jennifer Matthews1 and Lianping Ti1,3* Abstract Background: Drug checking is a harm reduction intervention aiming to reduce substance use-related risks by improving drug user knowledge of the composition of unregulated drugs. With increasing fears of fentanyl adultera- tion in unregulated drugs, this study sought to examine whether the expected type of drug checked (stimulant vs. opioid) was associated with timing of drug checking service utilization (pre-consumption vs. post-consumption). Methods: Data were derived from drug checking sites in British Columbia between October 31, 2017 and December 31, 2019. Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to examine the relationship between expected sample type (stimulant vs. opioid) and timing of service utilization. Odds ratios (OR) were calculated to assess the strength of this relationship. The Mantel–Haenszel (MH) test was used to adjust for service location. Results: A total of 3561 unique stimulant and opioid samples were eligible for inclusion, including 691 (19.40%) stimulant samples; and 2222 (62.40%) samples that were tested pre-consumption. Results indicated a positive association between testing stimulant samples and testing pre-consumption (OR 1.45; 95% CI 1.21–1.73). Regions outside of the epicenter of the province’s drug scene showed a stronger association= with testing pre-consumption (OR 2.33; 95% CI 1.51–3.56) than inside the epicenter (OR 1.33; 95% CI 1.09–1.63). -

Factsheet “Drug Checking”

Factsheet “Drug Checking” What is drug checking? “Drug-Checking“ is a harm reduction intervention aimed at users of psychoactive substances. It consist of two element – a chemical analysis of an illegally obtained psychoactive substance provided by the client; and a one-on-one counseling session. Drug checking is an acceptance-based, low threshold, anonymous and free-of-charge intervention targeting mainly, but not exclusively, people who use drugs recreationally. The chemical analysis is performed according to validated methods and by spe- cialized laboratories. In Switzerland, government-sanctioned drug checking services operate in the canton of Bern, the city of Zürich, in the cantons of Basel-Stadt and Basel-Land since 1998, 2001 and the mid-2010, respectively and in the canton of Geneva. Eve&rave, a non-governmental organization, offered drug checking services already in the early 1990s. How does drug checking work in practice? Drug checking is not only – some argue not even primarily – about chemically analyzing illegally ob- tained substances. Much more, it is a way to gain access to a population of drug users often otherwise inaccessible to prevention and harm reduction services. Clients must take part in a counseling session, are informed about the results of the analysis and are given harm reduction advice depending on the substance(s) and dosages detected in the analysis. Further, if unusual or unexpected substances (i.e. previously unknown substances, substances other than those the client believed to have bought, other psychoactive substances used as adulterants, potentially health-damaging adulterants) or unusually high dosages are detected, warnings are dis- seminated. -

An Overview of Forensic Drug Testing Methods and Their Suitability for Harm Reduction Point-Of-Care Services Lane Harper1, Jeff Powell2 and Em M

Harper et al. Harm Reduction Journal (2017) 14:52 DOI 10.1186/s12954-017-0179-5 REVIEW Open Access An overview of forensic drug testing methods and their suitability for harm reduction point-of-care services Lane Harper1, Jeff Powell2 and Em M. Pijl1* Abstract Given the current opioid crisis around the world, harm reduction agencies are seeking to help people who use drugs to do so more safely. Many harm reduction agencies are exploring techniques to test illicit drugs to identify and, where possible, quantify their constituents allowing their users to make informed decisions. While these technologies have been used for years in Europe (Nightlife Empowerment & Well-being Implementation Project, Drug Checking Service: Good Practice Standards; Trans European Drugs Information (TEDI) Workgroup, Factsheet on Drug Checking in Europe, 2011; European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, An Inventory of On-site Pill-Testing Interventions in the EU: Fact Files, 2001), they are only now starting to be utilized in this context in North America. The goal of this paper is to describe the most common methods for testing illicit substances and then, based on this broad, encompassing review, recommend the most appropriate methods for testing at point of care. Based on our review, the best methods for point-of-care drug testing are handheld infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and ion mobility spectrometry; mass spectrometry is the current gold standard in forensic drug analysis. It would be prudent for agencies or clinics that can obtain the funding to contact the companies who produce these devices to discuss possible usage in a harm reduction setting. -

Emerging Drugs of Abuse Are a Public Health Threat (Reference Committee E)

REPORT 2 OF THE COUNCIL ON SCIENCE AND PUBLIC HEALTH (A-17) Emerging Drugs of Abuse are a Public Health Threat (Reference Committee E) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Objective. Emerging drugs of abuse are a public health threat that needs actionable solutions from multiple stakeholders. Drug poisoning is the leading cause of injury death in the United States and drug poisoning deaths are at the highest level ever recorded. The Council on Science and Public Health initiated this report to bring attention to this public health issue and offer recommendations to address it. Methods. English-language articles were selected from a search of the PubMed database through January 2017 using the search term “emerging drugs of abuse,” coupled with “synthetic cannabinoid,” “synthetic cathinone,” “stimulant,” “novel synthetic opioid,” “fentanyl,” “empathogen,” “psychedelic,” “dissociative,” “depressant,” and “public health;” and the search term “public health approach” in combination with “addiction” (not “gambling”), “substance misuse,” and “drugs.” Additional articles were identified from a review of the references cited in retrieved publications. Searches of selected medical specialty society and international, national, and local government agency websites were conducted to identify clinical guidelines, position statements, and reports. Results. New psychoactive substances (NPS) are quickly emerging, transient, and difficult to track. Although some coordinated public health responses have been used to combat NPS outbreaks, most strategies and solutions to address illicit drug use remain compartmentalized and disconnected, and are lacking the necessary information and data sharing capability. A need for a multifaceted, collaborative multiagency approach to substance use exists. Increased NPS surveillance and early warning systems informed by laboratories and epidemiologic surveillance tools resulting in actionable information that can quickly reach law enforcement, public health officials, physicians, and vulnerable populations are solutions to mitigate the growing NPS problem. -

AMB-FUBINACA an ALERT by Toronto’S Drug Checking Service | October 22, 2020

Synthetic cannabinoid circulating in Toronto’s unregulated drug supply: AMB-FUBINACA An ALERT by Toronto’s drug checking service | October 22, 2020 What is the purpose of this alert? Between September 18 and October 13, 2020, a synthetic cannabinoid, AMB-FUBINACA, was found in 6% of the expected fentanyl samples checked by Toronto’s drug checking service (7 of 118 samples). AMB- FUBINACA was found in trace amounts (less than 2% of drugs found), alongside fentanyl, caffeine, heroin, and other fentanyl-related drugs. These samples were collected in Toronto’s east end, west end, and downtown core. The presence of AMB- FUBINACA was not expected by those who submitted these samples to be checked. AMB-FUBINACA has not been found consistently by Toronto’s drug checking service since November 2019. Other synthetic cannabinoids, like ACHMINACA, have also been found by Toronto’s drug checking service (mostly throughout May and June 2020). Since Toronto’s drug checking service launched in October 2019, synthetic cannabinoids, like AMB-FUBINACA and ACHMINACA, have been found in 4% of the expected fentanyl samples checked (27 of 701 samples). What is AMB-FUBINACA? AMB-FUBINACA is a synthetic cannabinoid. Synthetic cannabinoids are manufactured to be like THC, which is the main psychoactive component in cannabis, but can produce significant negative and unexpected effects. AMB-FUBINACA is very strong. In fact, it has been reported to be hundreds of times stronger than THC. The effects of synthetic cannabinoids may be intense – even by consuming very small amounts. Common side effects include distorted perception of time, having difficultly moving, increased heart rate, hallucinations, paranoia, confusion, fear, agitation, anxiety, nausea, and vomiting. -

What?S in Toronto?S Drug Supply? Results from Samples Checked by Toronto?S Drug Checking Service January 1 ? December 31, 2020

What?s in Toronto?s Drug Supply? Results from Samples Checked by Toronto?s Drug Checking Service January 1 ? December 31, 2020 April 21, 2021 Contents Acknowledgements 3 About Toronto?s Drug Checking Service 4 Service Operations: 2020 at a Glance 5 COVID-19: Implications for Service Delivery 6 Results from Samples Checked: January 1 ? December 31, 2020 7 Key Findings 8 Checked Samples by Sample Type 9 Checked Samples by Expected Drug 10 Opioids 11 Expected Fentanyl Substances 11 Expected Heroin Substances 13 Expected Percocet Substances 14 Expected Carfentanil Substances 14 Stimulants 15 Expected Cocaine Substances 15 Expected Methamphetamine Substances 16 Expected Crack Cocaine Substances 17 Expected Amphetamine Substances 18 Psychedelics 19 Expected MDMA Substances 19 Expected Ketamine Substances 20 Expected LSD Substances 20 Expected 2C Class Substances 20 Expected GHB Substances 20 Depressants 21 Expected Benzodiazepine Substances 21 Drug Dictionary 22 Tips & Help 24 Notes 26 Reporting Standards for Drugs Found 26 Noteworthy Drugs (!) 26 Limitations of Toronto?s Drug Checking Service 27 Contact 28 2 Acknowledgements We acknowledge the members of our community advisory board, our partner organizations, and those that have lost their lives ? both in the ongoing drug poisoning crisis and long before ? due to policies of drug criminalization. We acknowledge that the land on which we operate Toronto?s drug checking service is the traditional territory of many nations including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee, and the Wendat peoples, and is now home to many diverse First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. We acknowledge that racialized communities and survivors of colonization are disproportionately impacted by unjust drug policies.